CAN SMART SPECIALISATION HELP OVERCOME THE REGIONAL INNOVATION PARADOX ?

advertisement

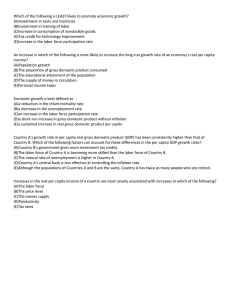

CAN SMART SPECIALISATION HELP OVERCOME THE REGIONAL INNOVATION PARADOX ? UCL-SSEES, London, 26/06/2013 Paper co-authored by: Alessandro Muscio Università degli Studi di Foggia (Italy) Email: al.muscio@unifg.it Lorena Rivera León & Alasdair Reid Technopolis Group, Brussels (Belgium) Email: lorena.rivera.leon@technopolis-group.com Email: alasdair.reid@technopolis-group.com A decade ago… "The regional innovation paradox refers to the apparent contradiction between the comparatively greater need to spend on innovation in lagging regions and their relatively lower capacity to absorb public funds earmarked for the promotion of innovation and to invest in innovation related activities, compared to more advanced regions.” (Oughton et al., 2002) What has happened since ? Geopolitical situation: 12 new Member States – mainly ‘transition economies’ Shift Economic power – shift of trade and market demand towards BRICs, economic crisis after ‘growth bubble’. Innovation systems have ‘opened’ and ‘internationalised’ of EU funds towards Eastern Europe (EE) increased challenge to create/attract/retain innovation resources in regional (and national) systems. Global challenges – environmental sustainability from inconvenient truth to desperately seeking solution. And diversity persists in governance performance “the quality of governance (QoG) is highly correlated with regional indicators of socio-economic development and levels of social trust…there thus seems to be ‘four Europes’ with respect to QoG” (Charron et al, 2012): The top performers: Nordic, Germanic & Anglo-Saxon countries. The second tiers consists of Mediterranean countries plus the two best performers in Central-Eastern Europe (Estonia and Slovenia). The third consists of post-communist EU Member States and, significantly, two southern European countries, Italy and Greece. The fourth group is the most recent Member States: Bulgaria and Romania Is the Regional Innovation Paradox a persistent phenomenon ? Our (draft) paper : Reviews the literature and evidence on innovation systems, regional policy and the regional innovation paradox We examine the specific case of the central and Eastern European (post-)transition ‘innovation systems’ and what the new ‘smart specialisation’ mantra could mean – linking it to the NSE arguments on initial endowments, institutions and comparative advantage. We then test empirically whether the regional innovation paradox is still a factor impinging on the effective use of EU Cohesion Policy to foster structural change through innovation intensive investment. Regional innovation paradox: open questions 1) We investigate the determinants of regional economic performance to check if EU funds promote an increase in performance? Less favoured regions need investment in innovation, receive money but…do they grow? Value Added=f(EC funding, control factors) 2) Less favoured regions need investment but cannot absorb it because of their lower governance capacity Does past absorption of EC funding allow regions to leverage ‘more’ EC funding in future rounds ? Is an effective use made of EC funding already absorbed 3 indicators (EC funding, HRST, EC funding per HRST) EU funding and Innovation performance – Evidence from the Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2012 Empirical analysis Empirical work is based on an econometric analysis of regional data analysed at the NUTS2 level for the period 2000-09. We distinguished between type of region by Structural Fund Objective ‘Convergence’ and Regional Competitiveness and Employment’ We tested specifically for a ‘location’ effect of being an Eastern European (EE) region = Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. Data used Eurostat data was used for for indicators of value added, public and business R&D, population and human resources employed in science and technology (HRST). DG REGIO data on Structural Funds expenditures for the period 2000-06 and Structural Funds allocations for 2007-13. Data on regional participation in the research Framework Programmes 6 and 7 was sourced from E-CORDA. Description of variables used in the econometric analysis Variable( Definition( Type( Source( annual(average(VA(per( capita(growth(2000;09( log(SF2007;13((Core(RTDI( &(Business(Innovation)( per(capita( region(in(EE(country( Average(annual(growth(rate(of(value(added(per(capita( over(the(period(2000;09.( Allocation(of(Structural(Funds(2007;13(per(capita(in(the( areas(of("Core(RTDI"(and("Business(Innovation".( continuous( Eurostat( log,( continuous( DG(Regio( Localization(of(the(region(in(an(Eastern(European( country.( Value(added(per(capita,(stock(level(in(the(base(year( 2000.( Framework(Programme(6(total(subsidies.( dummy( ;( log,( continuous( log,( continuous( log,( continuous( Eurostat( log,( continuous( log,( continuous( log,( continuous( log,( continuous( Eurostat( log(value(added(per( capita( log(FP6(total(funding(per( researcher( log(SF2000;06((Core(RTDI( &(Business(Innovation)( per(capita( log(BERD(per(capita( log(HR(S&T(/(population( log(economic(activities( Herfindahl(index( ! Expenditure(of(Structural(Funds(2000;06(per(capita(in( the(areas(of("Core(RTDI"(and("Business(Innovation".( Business(expenditure(for(R&D(per(capita,(stock(level(in( the(base(year(2000.( Share(of(population(employed(in(Science(&( Technology,(stock(level(in(the(base(year(2000.( Number(of(economic(activities,(stock(level(in(the(base( year(2000.( Herfindahl(index(in(the(base(year(2000.( E;CORDA( DG(Regio( Eurostat( Eurostat( Eurostat( Step 1: does EU funding drive value added (VA) growth ? The econometric analysis tests the impact of access to EU funding on regional economic growth. We assessed whether access to SFs and FPs funding drives to any extent VA growth and in particular, if these subsidies have any effect on EE regional growth performance. Step 1: results OLS$regression$ (1)$ (2)$ Dep.$Var.:$annual$average$VA$per$capita$growth$2000A09$ $$ $$ $$ region$in$EE$country$ 0.0988**$ 0.0674**$ $ [0.0202]$ [0.0183]$ log$value$added$per$ capita$ A0.0215**$ A0.00614$ $ [0.00807]$ [0.00772]$ log$fp6$total$funding$per$ researcher$ 0.00272**$ 0.00354**$ $ [0.000849]$ [0.000930]$ log$sf00A06$core$ RTDI+Business$ 0.000842$ A8.96eA05$ Innovation$per$capita$ $ [0.00151]$ [0.00142]$ int.$log$sf00A06$core$ RTDI+Business$ Innovation$per$capita$&$ EE$ A0.0256**$ A0.0226**$ $ [0.00369]$ [0.00307]$ log$BERD$per$capita$ $ A0.00694**$ $ $ [0.00149]$ int.$log$BERD$per$capita$ &$EE$ $ 0.0131**$ $ $ [0.00252]$ log$HR$S&T$/$population$ $ $ $ $ $ log$economic$activities$ $ $ $ $ $ Herfindahl$index$ $ $ $ $ $ Constant$ 0.217**$ 0.0966$ $ [0.0789]$ [0.0730]$ $ $ $ Observations$ 232$ 214$ RAsquared$ 0.536$ 0.618$ Robust$standard$errors$in$brackets$ **$p<0.01,$*$p<0.05,$+$p<0.1$ “convergence” effect confirmed FP6 research subsidies drives growth very modestly SF 2000-06 did not drive VA growth significantly. But Access to SF had a lower effect on growth in EE regions than in other European regions ! ! (3)$ (4)$ $$ 0.0622**$ [0.0197]$ $$ 0.0412+$ [0.0230]$ A0.00888$ [0.00838]$ A0.0205**$ [0.00780]$ 0.00330**$ [0.000955]$ 0.00403**$ [0.00108]$ A7.71eA05$ [0.00143]$ A0.00110$ [0.00174]$ A0.0228**$ [0.00288]$ A0.00759**$ [0.00151]$ A0.0245**$ [0.00394]$ A0.00952**$ [0.00174]$ 0.0136**$ [0.00248]$ 0.00794$ [0.00582]$ $ $ $ $ 0.143$ [0.0865]$ $ 214$ 0.622$ 0.0152**$ [0.00303]$ 0.0228**$ [0.00743]$ 0.000117$ [0.00201]$ A0.103+$ [0.0592]$ 0.318**$ [0.0819]$ $ 169$ 0.650$ Step 1: results (continued) BERD expenditure has a negative impact on growth ! A finding to interpret with some caution: The result is very small - for 100% increase in BERD per capita, VA per capita diminishes by less than 1% There is a parabolic concave relationship between BERD and growth – with to the left of the maximum point EE and other low income European regions and to the right RCE regions with high levels of BERD per capita. Some sort of “Swedish Innovation Paradox” is taking place in Europe, with high levels of expenditure on R&D not driving economic growth. The opposite in the case for EE regions, where we estimate that BERD investments drive economic growth, even if by a small margin. Finally, our results confirm the findings of other economists that investment in HRST has a positive effect on economic growth Step 2: Testing the paradox Second step of the econometric analysis is based on the same model but we introduced as a dependent variable regional access to EC SFs for the current programming period 2007-13 expressed in log. Low income regions have larger access to funding for the programming period 2007-13 but ceteris paribus location in EE countries does not have a significant impact on access to funding. Step 2 : results Cumulative effects are found for both FP6 and SF2000-06 funding, as larger participation in FP6 and larger access to SFs in the past drives access to funding in the current programming period. However, no significant difference in the impact of the absorption of SFs in 2000-2006 period between EE and other regions. As expected, given the mission of EC SFs, regions with lower levels of business expenditure in R&D have larger access to funding in the current programming period, especially those regions in EE countries. We found no significant effect of investments in HRST on allocations of SFs to RTDI in 2007-13. What do these results imply ? A first general finding is that SF RTDI funding has so far not made a significant contribution to growth especially in EE regions. Moreover, there is some evidence that the Regional Innovation Paradox is alive and kicking, as EE regions (that badly need funding) are not advantaged in terms of access to SF RTDI funding once all other factors are held constant (HRST, BERD, etc.). Conclusions: smart specialisation in (post-)transition economies Our work suggests that the 2014-20 Structural Fund period may be a make or break one for the EE countries if they are to achieve structural change and break-out of the ‘middle-income trap’. Evidence suggests the current EE innovation systems may be reaching (have reached) a ceiling in terms of capacity to absorb RTDI (infrastructure) funds. The potential of smart specialisation strategies to foster ‘innovation-driven growth’ is seriously constrained by weak governance capacities. This constraint will bite not primarily at the strategic (priority setting) level but at the programme implementation level.