Central Norfolk Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2015

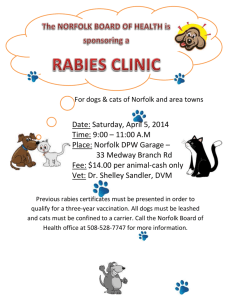

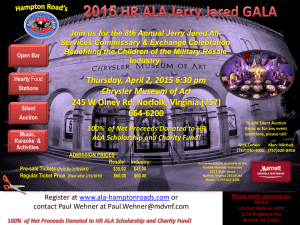

advertisement