Department of Economics Working Paper Series

advertisement

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

Prices and Quantities in Health Care Antitrust

Damages

by

R. Forrest McCluer

Greylock McKinnon Associates

Martha A. Starr

American University

No. 2014-3

January 2014

http://www.american.edu/cas/economics/research/papers.cfm

http://www.american.edu/cas/economics/research/papers.cfm

Copyright © 2014 by R. Forrest McCluer and Martha A. Starr. All rights reserved. Readers

may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means,

provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies.

2

Prices and Quantities in Health Care Antitrust Damages

R. Forrest McCluer*

Greylock Mckinnon Associates

Martha A. Starr

American University

January 2014

Abstract

Antitrust analysis conventionally assumes that illegal agreements among competitors raise prices and

lower quantities, relative to lawful competition. However, markets for healthcare services have

tendencies towards overprovision, which may increase when competition declines. This paper examines

this possibility using data from a well-known antitrust case in Wisconsin. We find that, in parts of the

state where physician groups illegally divided up markets, costs of physician services rose by about

10% more than they did elsewhere, with about half of this increase due to increased services. This

suggests that higher quantities can contribute to healthcare antitrust damages, along with higher

prices.

Keywords: Antitrust, healthcare, physician services, anticompetitive conduct, damages.

JEL Codes: I11, L4, K21, C43

* Please address correspondence to: R. Forrest McCluer, Greylock McKinnon Associates, One Memorial

Drive, Suite 1410, Cambridge, MA 02142, email: fmccluer@gma-us.com, tel: (703) 237-3010. This

paper was presented at the 3rd Biennial Conference of the American Society of Health Economists, at

Cornell University, June 20-23, 2010. We are grateful to Ana Aizcorbe, Cory Capps, Michael Chernew,

Randy Ellis, Ted Frech, Thomas McGuire, Jim Neiberding, Eileen Reed, George Schink, Robert Tollison,

and seminar participants at the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis for valuable comments on earlier

versions of this work. McCluer worked in support of plaintiffs in the Marshfield Clinic cases. The views

expressed in this paper are those of the authors and cannot be attributed to Greylock McKinnon

Associates or any other employee or affiliate thereof. Remaining errors are the responsibility of the

authors.

I. Introduction

A core concern in antitrust analysis is whether an alleged reduction in competition in a given market has

increased prices and reduced quantities supplied, causing allocative inefficiencies and a decline in

consumer welfare. In their seminal framework linking economic reasoning and antitrust law, Landes and

Posner (1981) focused attention on loss of output as the primary cost of the exercise of monopoly power.

Easterbrook (1984) expresses a similar view that, if arrangements are anticompetitive, the output of

those engaging in them must fall. Going beyond this view, Bork (1978) argued that, because consumer

welfare is the proper focus of antitrust analysis, one needs to examine the specifics of a case to

determine whether consumers have been harmed by a given set of anti-competitive practices, without

assuming that a reduction in quantity has to be involved.1 By this reasoning, practices that do not reduce

or possibly even increase output could be the subject of antitrust scrutiny. For example, vertical price

restraints that increase output above the levels that would have been demanded in the absence of

restraints can be welfare reducing (Comanor 1985, Blair and Fesmire 1994, Rey and Tiore 2003).2

Similarly, agreements among producers to restrict or divide markets are treated as illegal per se,

regardless of how they affect quantity or price, because they inherently reduce the range of choices that

consumers face (ABA 1996:181). Nonetheless, the idea that quantity reductions will be found in cases

where firms are engaged in illegal competitive practices remains an expectation, as indicated in the

frequently-cited ruling: “Unless a contract reduces output in some market, to the detriment of

consumers, there is no antitrust problem.”3

Issues of quantity can be especially problematic in antitrust cases related to markets for healthcare

services. Consumers receive utility not from healthcare services per se, but rather from the benefits

these services provide in terms of maintaining or improving their health (Grossman 2000). As they lack

specialized medical knowledge, they need to rely on physicians and other trained professionals to

determine the levels and mixes of services that best help to advance their health goals. Yet incentives

that physicians face may often cause them to recommend more services or different mixes of services

than would be consistent with optimization of social welfare. For one, because patients with health

insurance pay only a fraction of the costs of services they receive, physicians acting as their agents may

provide more referrals or recommend more tests or treatments that would be warranted if patients

faced the full costs of the services they received (Feldstein 1973, Pauly 1986, McGuire 2000). For

another, traditional fee-for-service medicine has tended to reinforce tendencies towards overprovision,

1

As Bork (1978: 34) has stated, “[t]he goal of the law was clearly defined as the maximization of

consumer welfare, and a dynamic principle was built into the rule of reason so that the interpretation

of the law could change and adjust in its pursuit of that goal as economic understanding advanced.”

Others have been more explicit in identifying pure consumer welfare as the basis for antitrust analysis

(e.g. Salop 2005).

2

See Gaynor and Vogt (2000) for discussion of vertical restraints in health care.

3

Chicago Professional Sports Limited Partnership v. National Basketball Association (Chicago Prof. Sports

Ltd. II), 95 F.3d 593, 597 (7th Cir.1996)).

4

as it rewards physicians for providing higher levels of services, rather than for efficiently using

resources to maintain and improve patients’ health (Robinson 2001; Emanuel and Fuchs 2008).

From the point of view of antitrust policy, the issue of interest is whether the extent of overprovision in

a given healthcare market is exacerbated or attenuated by changes in competition. Economic models

allowing for possibilities of overprovision provide ambiguous predictions in this respect. In a model in

which patients prefer to receive referrals to specialists, Iverson and Ma (2011) find that reductions in

competition in markets for physician services will tend to lower levels of service provision because, if

physicians do not have to compete as rigorously to attract and retain patients, they will not cater as

much to patients’ requests for referrals. In contrast, in Allard, Léger and Rochaix’s (2009) model in

which patients face costs of switching from one physician to another, a decline in competition tends to

increase overprovision because under less competitive conditions, physicians have to worry less about

losing patients if they provide more services than patients would like.

More generally, Ma and McGuire (2002) call attention to the role of provider networks in controlling

utilization of healthcare services. In preferred-provider arrangements, health plans build networks of

providers who agree to accept discounted payments and controls over utilization (e.g. utilization

reviews, pre-admission authorizations, prior approvals, second opinions for costly procedures), in

exchange for higher patient volumes from the plan’s enrollees. When health plans have strong

bargaining power relative to provider groups, they have good ability to insist on adherence to utilization

targets, as they can credibly threaten to exclude high-utilization providers from their networks. But

when plans have weak bargaining power relative to provider groups (as when the pools of patients they

control are small, or there are few good-quality provider groups), they may not be able to credibly

threaten to exclude higher-utilization providers from their networks.4 This model too predicts that

overprovision will tend to rise when competition among providers declines, ceteris paribus, by eroding

health plans’ bargaining power relative to that of providers. But overall, the ambiguous predictions from

theoretical models as to how changes in competition should be expected to affect levels of services

provided in given healthcare markets suggest a need for further theoretical work in this area, as well as

empirical investigations of specific cases.

In view of this gap in understanding, this paper uses data from a well-known antitrust case from central

Wisconsin in which physician groups were known to have illegally divided up markets -- and asks what

happened to prices and quantities of physician services in that part of the state as the illegal

agreements phased in. The reduction in competition would be expected to increase prices of physician

services in the affected areas, relative to comparable areas that were unaffected by them; clearly this

represents a central part of the damages experienced by healthcare consumers and third-party payers.

But additionally, the plaintiffs in the case alleged that physicians in the area responded to the decline in

4

This parallels the bargaining framework used by the Federal Trade Commission to analyze hospital

mergers; see Town and Vistnes (2001) and Capps, Dranove and Satterthwaite (2003). See also Ho

(2009) on insurer-provider networks.

5

competition in part by increasing the quantities of services they provided to their patients, so that

higher output as well as higher prices contributed to damages.

This paper reexamines the question of whether output for physician services increased in central

Wisconsin when these illegal market-allocation agreements phased in, using data from 40 million health

insurance claims in the state in 1988-1995. A problem that arises in trying to quantify output of

physicians’ services concerns its heterogeneity, as services range from annual well-child visits to openheart surgery. The paper develops a method for disaggregating charges for physician services into

quantity and price components, using a measure of quantity that values services at their average prices

during the years covered by the analysis. This method bears some similarities to other work on indexes

for prices and quantities in health care (e.g. Berndt et al., 2001; Aizcorbe and Nestoriak 2011), but

whereas they are open-ended measures intended to monitor price changes on an ongoing basis, the

method here focuses on quantifying effects of illegal conduct on prices and quantities in a given time

and place.

The next section of the paper describes the case analyzed in the paper, in which Marshfield Clinic, a

large multi-specialty group practice known for being a high-quality provider in Wisconsin, played a

central role. The third section presents the data to be used and explains the method for disaggregating

charge data into price and quantity components. It also describes the difference-in-difference regression

models used to compare changes in output and prices in the areas affected by the illegal marketallocation agreements, to those in otherwise similar areas that were not. The fourth section presents

empirical results, and a final section concludes. In brief, we find that an important share of the extra

increases in costs faced by patients in the part of the state where illegal arrangements were in effect,

relative to increases faced by patients elsewhere, were associated with increased provision of services.

Estimates from our preferred specification suggest that average annual patient costs rose by about 10%

more in the part of the state in which anticompetitive agreements were in effect than they did

elsewhere in the state, ceteris paribus, with an increase in the quantity of services provided accounting

for about one-half of the extra increase. This underlines the need to consider whether higher quantities,

as well as higher prices, may contribute to healthcare antitrust damages.

II. The Marshfield Clinic class action suit

In the 1990s, a series of lawsuits were brought against the Marshfield Clinic of central Wisconsin, one

of the largest private, multi-specialty group practices in the United States. At that time, the clinic

employed 300-400 physicians who practiced at the main clinic in Marshfield and 24-27 satellite clinics

in the surrounding areas. Most of Marshfield Clinics’ physicians served on the medical staff at St.

Joseph's Hospital, a 524-bed tertiary-care teaching institution adjacent to the main clinic. In addition,

the Clinic owned and operated its own managed-care organization, Security Health Plan. It also had a

6

varied array of business arrangements with other physicians and healthcare providers in the area,

aiming to create a regionally integrated healthcare system known for its quality of care. 5

Table 1 provides a brief chronology of the cases against Marshfield Clinic, as background to the issues

discussed in the current paper. The initial suit was brought by Blue Cross-Blue Shield of Wisconsin and

its HMO, Compcare, charging that Marshfield Clinic and its HMO, Security Health Plan of Wisconsin,

were monopolizing physician services, fixing prices, and illegally dividing markets with competitors. At

that time, the case raised thorny new legal and conceptual issues related to correct definitions of

healthcare markets and valid methods of distinguishing between legal vs. illegal factors contributing to

higher healthcare costs.6 While the jury was persuaded by the charges against Marshfield, the

appeals-court judge, distinguished legal thinker Richard Posner, took issue with much of the analysis

presented in the first case, overturning most of the initial findings and remanding the case to district

court, with instructions to plaintiffs to limit estimates of damages to those associated with illegal

division of markets only. Damage estimates presented in the remand phase were in turn rejected by

the district-court judge, among other things for failing to distinguish between legal and illegal factors

contributing to Marshfield Clinic’s higher patient costs. Summary judgment was issued in Marshfield’s

favor; BCBS appealed unsuccessfully.

Subsequent class-action litigation (referred to as ‘Rozema’ after the named plaintiffs) charged

Marshfield Clinic and other healthcare providers with entering into business arrangements that illegally

restricted trade and increased costs of physician services for people who lived in an eight-county “area

of influence” (AOI).7 Defendants in the case in addition to Marshfield Clinic were Security Health Plan,

the Marshfield-owned HMO; North Central Health Protection Plan, an HMO based in Wassau; and

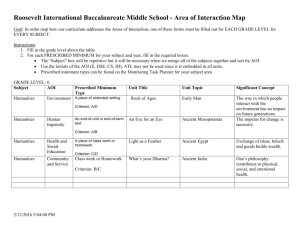

Rhinelander Medical Center, based in Rhinelander.8 Figure 1 shows the AOI and the defendants’ main

locations. As evidence in the case established, agreements among these providers aimed to reduce

competition between them via such routes as not opening offices in each others’ territories, not

actively marketing in each others’ areas, and not building specialty practices in places where other

providers’ had already established them.9 Some of these agreements had started as early as 1978,

but evidence presented in the case established that they had expanded in breadth and scope after

1991.

5

The Clinic had has continued to grow since then, presently employing some 776 physicians and

6,600 support personnel in 54 locations (Marshfield Clinic 2012).

6

For further discussion of the Marshfield case and the issues it raised, see Troupis (1995), Sage

(1997), Haas-Wilson and Gaynor (1998), Greenberg (1998), Coombs (2005), and McCluer and Starr

(2013).

7

Counties in the AOI included Clark, Price, Lincoln, Oneida, Marathon, Taylor, Portage, and Wood.

Formally, the class constituted people living in the AOI who had acquired physician services in the AOI

after July 24, 1992 (as entered in a ruling after expert reports had been submitted).

8

The case originally included another defendant, Rice Clinic located in Stevens Point (Portage County),

but the judge ruled there was insufficient evidence of its involvement in illegal agreements.

9

As a Marshfield official wrote of discussions held with Rhinelander in 1991, “We do not want to see

ourselves ‘knocking heads’ for the same services for the same patient population” (quoted in Judge

Crabb, Order and Opinion, Oct. 2, 1997).

7

Experts for the plaintiffs argued that these agreements not only enabled physicians to charge

relatively high prices for their services, but also to provide higher quantities of services than they

would have provided under legal competitive conditions. This possibility had come up in the earlier

Marshfield case, but was dismissed by Judge Posner as “a strange inversion of the usual logic of

cartelization, which is that cartelists drive up the market price by (or with the effect of) restricting

their output.”10 In the class-action case, however, the plaintiffs’ experts developed the argument more

fully, both by referring to scholarly research in health economics and by presenting estimates of

damages that distinguished between those associated with higher prices and those associated with

higher levels of services.11 While the judge called the inclusion of increased quantity in damages “a

drastic departure from antitrust economics and unsupported by case law”, she did not think it could be

dismissed on this grounds alone, and on the contrary viewed the evidence as sufficient for a

reasonable jury to conclude that “plaintiffs paid more for physician services because of defendants'

unlawful conduct” (Judge Crabb, Order and Opinion, Oct. 2, 1997). Thus, she declined to grant

summary judgment in the case, and it was subsequently settled.12

IV. Data and methodology

The data used for the analysis come from 40 million insurance claims for professional services

submitted to Blue Cross-Blue Shield (BCBS) by all subscribers residing in the state of Wisconsin in

1988 to 1995.13 This is the same data as was used for the Rozema class action suit. During these

years, BCBS was the largest provider of group health insurance in the state of Wisconsin, having some

10-13% of the statewide market.14

The claims data report basic information on the patient (age, gender, relationship to the subscriber),

the provider, and codes indicating the specific services the patient received. Some 400,000 unique

medical procedures associated with physician services are found in the data, where ‘procedures’ are

10

152 F.3d 588 (7th Cir. 1998). Posner conceded that McGuire’s argument was “a possibility,” but

thought “there [was] no evidence of it”. See McCluer and Starr (2013) for discussion.

11

A first expert, H. E. Frech III, argued that moral-hazard problems in healthcare can lead to

overprovision of services, with anti-competitive conduct tending to increase utilization. As Judge Crabb

summarized his opinion, “ … Dr. Frech states that health care markets are subject to economic forces

different from other industries. It is his opinion that most Americans consume a higher-than-optimal

level of health care because of the moral hazard created by health insurance. When market competition

and managed care are operating properly, they reduce the utilization of physician services. According to

Frech, anticompetitive conduct leads to higher utilization” (977 F. Supp. 1362 (W.D. Wis. 1997)).

12

See Associated Press (1997). In the Rozema case, Judge Crabb ordered that Rice Clinic be dropped

as a co-conspirator and that patients residing in Portage County be dropped from the class (Judge

Crabb, Order and Opinion, October 2, 1997); this ruling came after the econometric analysis was

submitted. Damages were computed as 6.9% times the total health care expenditures of residents of

the AOI. The case settled for a portion of the estimated damages (Coombs 2005: 188).

13

Cases in which out-of-state residents travelled to Wisconsin to receive medical care are excluded

from the analysis to avoid issues of sample-selection bias.

14

Figures from Table E, Office of the Commissioner of Insurance, State of Wisconsin (1988-1995).

8

defined as unique combinations of the characteristics of the service: the Current Procedural Terminology

(CPT), the standard 5-digit code used to classify physician services for billing purposes; three modifiers

of the CPT (type of service, place of service, and number of units of service); the type of provider

(medical doctor or osteopath); and the provider’s specialty (e.g. general practitioner, radiologist, or

thoracic surgeon). The ‘prices’ in the analysis are the charges submitted to BCBS, not payments made

by BCBS; this ensures that measured differences in prices across areas reflect differences in providers’

charges, rather than features of insurance coverage (e.g. deductibles, copayments, negotiated prices).

We use the claims data to compute total real annual costs per patient, then use an index approach to

decompose variations in total costs into price and quantity components. The first step is to compute

total annual costs of physician services for individual i in year t,

:

(3)

where

is the price charged to individual i for service j obtained from provider k in year t, and

is the related quantity. Aggregating all charges over each year for individual patients yields 2.26

million individual-year observations for individuals under age 65.15 (We omit 41,504 records for

individuals aged 65 and over from the analysis, given that the vast majority of people in this age

group have their primary health insurance coverage through Medicare). While some individuals in the

data have records for multiple years, complexities of matching the records imply it is difficult to

structure the individual-year records into a complete (imbalanced) panel data set.16 As a result, we

opt to analyze the data as a pooled cross-section sample instead. To take into account general

inflation in healthcare costs over the period, all prices are deflated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’

consumer price index (CPI) for all medical services (1995=100).

Next we take averages of prices for each service j across all individuals i, all providers k, and all years:

15

Note that some individuals in the data were covered under a BCBS plan for only part of the year. We

have not tried to convert partial-year records to full-year equivalents, as it is difficult to identify such

cases with certainty.

16

For example, some individuals submit claims in early years of the period analyzed and again in later

years, but we cannot tell whether they incurred no costs in the intervening years or whether they

were not covered by a BCBS plan.

9

________________________

where we refer to

(4)

as the index price for service j. Then specific prices paid for a service can be re-

expressed as deviations from its index price, permitting us to re-write (3) as:

(5)

where the term

is the deviation from the index price associated with individual i’s purchase of

service j from provider k in year t. Re-arranging and letting

be the total quantity of service j

received by individual i in year t (i.e. summing over providers), the individual’s total costs of physician

services can be decomposed as follows:

(6)

=

The first term

(7)

, is a constant-price index of the quantity of services received by individual i in year

t, where outputs are valued at their index prices. This represents the primary measure of ‘quantity’

used in our analysis. In effect,

holds prices constant at average levels prevailing in the period

under investigation, so that increases in

over time necessarily come from changes in quantities of

services received and/or shifts in the composition of services towards those with higher average

prices.17 The second term,

, is a measure of ‘price deviations’ faced by individual i; it is a

weighted average of the differences between the price the individual was charged for a given service

at time t and the index price for that service, with weights given by the quantity of the service

17

In this sense, the quantity measure differs from a standard constant-price measure of output, which

values quantities at prices from a given base year.

10

received by the individual in year t. Thus,

can rise over time either because price deviations of

the services acquired by individual i have increased and/or because the composition of services has

shifted to services with higher deviations. For damage estimation, the key question is whether

differential increases in quantities of services contributed to differential increases in costs among

patients with given characteristics residing in the AOI, compared to counterparts who lived elsewhere.

Table 2 and Figure 2 show averages for these variables for individuals residing in and out of the eightcounty AOI. In 1988-90, average total annual costs were no higher in the AOI than they were in the

rest of the state; thereafter, however, they exceeded them by $50-100 (roughly 6.5 to 11.5%). This

is consistent with information presented in the class-action case that the market-allocation

agreements in which Marshfield Clinic was involved increased in breadth and scope after 1991. In the

years when average total annual costs were higher in the AOI than in the rest of the state, the higher

quantity of services tended to be more important in contributing to the higher costs than the price

deviation, although with some variation in the relative importance of the two factors from year to

year. Taking the 1991-95 period as a whole, average annual costs were $84 higher in the AOI than

they were elsewhere, where $68 of the difference (or 80.5%) came from the higher quantity index.

Of course, there may be socio-demographic differences between the AOI and the rest of the state that

contribute to the relatively high quantities of physician services received in the AOI. Notably, because

the areas served by Marshfield Clinic tend to be relatively rural, the baseline health of the population

may tend to be lower than it is elsewhere due to lower income levels, lower levels of education,

different occupational profiles, etc. Similarly, levels of competition among providers tend to be lower

in rural areas, so it is possible that the higher price deviations registered in the AOI reflect the

‘naturally’ higher pricing power of rural healthcare providers, rather than effects of illegal divisions of

markets.

Thus, we use a regression framework to account for legitimate factors explaining variations in total

annual costs, the quantity index, and price deviations across areas. The standard ‘benchmark’ method

of estimating damages estimates a regression of the form:

=

where

+

+α

+

(8)

is a vector of factors expected to influence the individual’s healthcare costs (e.g. age,

gender, type of health insurance, etc.),

is a vector of year dummies intended to capture broad-

based changes in real healthcare spending, and

is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the individual

11

lives in the AOI. Then the estimated coefficient

α indicates whether total annual costs per patient are

higher in the AOI than they are elsewhere, ceteris paribus. To gauge the relative contributions of

higher quantities and higher prices to higher charges in the AOI, we can run regressions of the form:

=

+

+

+

(9)

=

+

+

+

(10)

,

However, if

and

contain unmeasured but lawful sources of variation in costs, quantities

and prices across areas and these correlate with

, then regression estimates of ,

and

will give biased representations of effects of illegal conduct in the AOI. A common concern in this

respect is that the quality of care may vary systematically between physicians in one area and the

other, and/or that patients with given observed characteristics may differ in unobserved ways that

make their health conditions more complex than those of patients elsewhere, so that differences in

costs, quantities and prices between the AOI and ROS reflect hedonic differences in the services

received.18

This problem can be addressed by making use of the fact that, while the data cover the 1988-95

period, the scope of the agreements behind the illegal market allocation broadened after 1991. Thus,

we can estimate difference-in-difference regressions that in effect take initial differences in levels of

the dependent variable between the AOI and ROS to be reflective of persistent unobserved

heterogeneities between the two areas; then controlling for other observable factors that may have

caused the dependent variable to change between 1988 and 1995, an increase in that variable over

that period that is greater in the AOI than it is the ROS is suggestive of an effect of the market

allocation. Specifically, we run regressions of the following form:

=

18

+

+

+

(16)

See McCluer and Starr (2013) for discussion. This issue was more important in the first phase of the

Marshfield-related litigation, which compared patient costs between patients who received a majority

of their care from Marshfield clinic to otherwise similar patients who received their care from other

providers.

12

for the three dependent variables; this amounts to including year dummies that differ between the

AOI and ROS. Then the test for an effect of the illegal market allocation for a given dependent variable

is:

ΔΔ =

-

} - {

-

}

(17)

See Abadie (2005) for methodological discussion and McCluer and Starr (2013) for an application

using data from the remand phase of the Marshfield case.19

In principle, some part of the differential increase in quantity in the AOI could have been associated

with increases in the quality of care than would have been warranted under an economic calculus of

costs, benefits and risks; in this case, the DID estimate of the effect of the illegal market agreement

would overstate the anticompetitive increase in quantity. However, in the present case direct review of

evidence on the quality of care did not suggest any basis for concern about a possible bias from this

source. Notably, at the outset of the period Marshfield Clinic was widely perceived to have a

substantial quality advantage over other providers in the state; while it continued to work on

improving its procedures and facilities in the period, its efforts were well in line with those of other

providers in the state.20 So while we do not expect there to be bias from differential changes in quality

in the present case, the possibility should be investigated in others, given that correct estimation of

damages requires all legal sources of differential outcomes across providers or across areas to be

accounted for.21

Table 3 gives definitions of the variables used in the regression analysis along with sample means. Our

information on individual characteristics is limited to what is reported on insurance claims, but these

cover many of the factors that would be expected to affect use of healthcare services, especially age,

gender, marital status, and type of insurance plan (general indemnity, Federal government workers,

19

This differs somewhat from the standard DID specification, which uses a stark division between a

before-and-after period to identify the effect of interest (Rubinfeld 2010). In the present case, we

favor the more flexible specification implied by (16), given that the illegal market-allocation

agreements were known to have phased in at different times in different places within the AOI. Still,

for purposes of comparison, we also estimated standard before-and-after DID regressions, using the

formal definition of the class period (from 1992 on) as the market allocation period. Results in this

case show an increase in total patient costs that is, not surprisingly, somewhat smaller than is the

case when 1988 and 1995 are compared (i.e. an increase of $64 from 1988-91 to 1992-95, vs. $83

from 1988 to 1995); however, the standard method traces a much larger share of this increase to

increased quantity (90% vs. 53%).

20

For example, in the remand phase of the trial, BCBS expert Thomas McGuire noted that the share of

procedures performed by specialists (rather than primary care physicians) did not rise faster at the

Clinic than it did elsewhere, as might be expected if its quality of care was improving at an

extraordinary rate. See also McCluer and Starr (2013).

21

Hammer and Sage (2002) and Vogt and Town (2006) suggest that claims of increased quality

accompanying increases in market power should be looked at skeptically, as they are not often

substantiated by review of clinical outcomes, Moreover Gaynor (2006) finds that quality of care is

better favored by competition than concentration.

13

etc.).22 We incorporate effects of age and gender by interacting age ranges with gender; this allows

age profiles of health costs, quantities and price deviations to differ between men and women. To

account for other differences across areas that may contribute to the higher costs found in the AOI,

we include county-level measures of the socio-demographic characteristics of the population,

including: the share of the population with a high school education or more, the population density,

the unemployment rate, real per capita income, real medical-assistance payments per capita, and

birth and death rates.

The basic specification closely parallels that which was used in the Rozema class action case. We also

estimate a number of alternative specifications, adding explanatory variables and varying the

estimation method used. A possibility that came up repeatedly in the Marshfield-related litigation

cases was that healthcare prices in given parts of Wisconsin were relatively high because of legal

competitive factors, instead of or in addition to illegal market division. First, because ratios of

physicians to population are known to be relatively low in areas of low population density, and the AOI

is largely rural, this may confer some ‘natural’ ability to price above marginal costs and/or provide

extra services to their patients unrelated to illegal behavior.23 Because the counties in the AOI all have

relatively low population density yet vary in the degree of concentration in the market for physician

services, we add the Herfindal-Hirshman index (HHI) to the variables included in the regression

analysis. The HHI measures market concentration as the sum of the squared market shares of all

providers in the market; specifically, we measure it as the share of all billing events for all providers

used by residents of the county.24

Another issue related to legal competitive factors concerns effects that health-maintenance

organizations (HMOs) may have on prices and quantities (Baker 1994, Baker and Corts 1995, HaasWilson 2003). On one hand, if a given local market has a well-developed HMO sector, it may tend to

act as a check on price increases, as insurance companies may negotiate harder for lower prices to

limit patients’ out of pocket costs and avoid loss of business to managed care. Baker (1994) and Baker

and Corts (1995) refer to this as a ‘market discipline’ effect. In this case, total costs and price

deviations may tend to be lower in counties where HMO penetration is higher, ceteris paribus. On the

other hand, the more people have substituted into managed care in a given market, the more likely it

22

Identifying information such as name and address was either masked or not made available.

As Posner wrote in his opinion on BCBS’s appeal (65 F.3d 1406 (7th Cir.) 1995), “If the Marshfield

Clinic is a monopolist in any of these areas it is what is called a ‘natural monopolist,’ which is to say a

firm that has no competitors simply because the market is too small to support more than a single

firm. If an entire county has only 12 physicians, one can hardly expect or want them to set up in

competition with each other. … Twelve physicians competing in a county would be competing to

provide horse-and-buggy medicine.”

24

The HHI is commonly used in analyses of the competitiveness of health care markets (e.g. Lynk

1995, Schneider et al 2008). As discussed in Frech, Langenfeld and McCluer (2004), computing the

HHI in terms of the location of the patient rather than the provider avoids issues of sample selection

and case mix. We also ran the regressions using HHIs computed from providers’ shares of the value of

total billings rather than the total number; there is no qualitative difference in results, which is not

surprising given the high correlation between the two measures (0.95).

23

14

will be that those remaining in traditional indemnity insurance plans are likely to have worse

underlying health. Baker (1994) and Baker and Corts (1995) call this as a ‘market segmentation’

effect. In this case, total costs and quantities may be higher in counties where HMO penetration is

high, as the pool of patients remaining outside of the HMO sector will have relatively poor health.

To account for these possibilities, the regressions include a measure of HMO penetration, namely, the

share of the county’s population enrolled in an HMO. A complication is that some of the defendants in

the class-action suit were HMOs, including one wholly owned by Marshfield Clinic; consequently, if

people enrolled in defendant HMOs were included in the measure of HMO penetration, the degree of

competition coming from managed care in the AOI would be overstated.25 So in computing HMO

enrollment for counties in the AOI, we exclude people who were enrolled in Security Health Plan or

North Central Health Protection Plan from the penetration rate.

V. Empirical results

Table 4 presents results from the basic difference-in-difference specification, which controls for

sources of persistent unobserved heterogeneities between the AOI and ROS and uses differential

changes between the areas to gauge the effects of illegal competitive behavior. Before looking at the

comparison of changes in the AOI vs. ROS, it is first valuable to examine the estimated effects of the

other explanatory variables, which suggest that the specification captures a number of interesting

and/or expected variations across individuals in costs, quantity and price deviations. The results

indicate that, for both men and women, total annual spending on physician services rose significantly

with age; for example, total costs were $417.6 (=$767.5-349.9) higher for women in the age 55-64

age range than for otherwise similar women in the 25-34 age range, while for men the analogous

difference was $1165.1 (=$1161.9-(-3.2)). This is consistent with a large literature documenting the

strong dependence of healthcare costs on age (e.g. Alemayehu and Warner 2004). The increase

occurs earlier for women than it does for men, although for men spending rises relatively steeply from

age 45 on.26 In both cases, increases in spending with age are largely due to increases in the quantity

of services; estimates for the price-deviation equation show some shift towards relatively more costly

services after childhood, but it is modest compared to the increase in quantity.

Married subscribers had somewhat lower total spending on physician services than single subscribers,

ceteris paribus, which has mostly to do with the lower quantity of services acquired; for example, of

the $50.90 difference in spending between married and single subscribers, $48.40 was due to the

lower quantity index. This is broadly consistent with clinical evidence that people who have good

marriages and good networks of social relations tend to have better health (Cohen 2004, Parker-Pope

2010). Not surprisingly, total spending is substantially and significantly higher for people in high

insurance risk-sharing plans, where this is almost entirely due to very high quantity of services. Total

25

As McCrary and Rubinfeld (2009) caution, including covariates that are causally related to the

conspiracy on the right-hand side of a regression biases estimates of damages due to the conspiracy.

26

Note that results are for physician services only.

15

spending is also relatively high for subscribers enrolled in BCBS’s Federal Employee Program, and

relatively low for subscribers enrolled in national programs, where in both cases differences in the

quantity index are much more important than price deviations.

Among the county-level variables, total spending on physician services was relatively low for

individuals in counties with relatively high shares of the population with a high school degree or more;

the effect is due almost equally to lower quantity and a lower price deviation, although only the latter

effect is significant. Ceteris paribus, total spending was relatively high for people living in counties

with high population densities, due to both higher quantities and higher prices. Individuals in counties

with relatively high unemployment had relatively high total spending, due almost entirely to relatively

high quantities of services. This seems to run counter to Ruhm’s (2000) finding that ‘recessions are

good for your health,’ although the types of cyclicalities he identifies (e.g. motor vehicle accidents)

may affect spending on hospital services more than spending on physicians. Individuals in counties

with relatively high per capita income had relatively high spending due to both quantities and prices;

in contrast, those in counties with relatively high medical assistance per capita had relatively high

spending, due entirely to relatively high price deviations. Relatively high birth and death rates had no

significant effect on total spending or the quantity index, but they were associated with relatively low

price deviations.

Turning to the comparison of changes in the AOI vs. the ROS, the results indicate that, controlling for

other factors, total annual spending on physician services in the AOI rose by $303.6 between 1988

and 1995, while it rose by $231.0 in the ROS; the difference between the two of $82.6 is statistically

significant.27 This is consistent with the expectation that the illegal market-allocation agreements

boosted spending on physician services.28 With respect to the source of the increase, the estimates

show that both quantities and price deviations rose significantly in both the AOI and the ROS between

1988 and 1995, where the increases in quantities and price deviations were both larger in the AOI

than they were in the ROS. Looking at the decomposition of the $82.6 differential increase in total

costs in the AOI, the estimates suggest that $49 (59.3%) of this increase came from the greater

increase in quantity in the AOI relative to the ROS.29 This supports the expectation that some part of

the illegal market power acquired by physicians in the AOI due to the market-allocation agreements

resulted in intensification of service provision, in addition to higher prices.

Table 5 shows results incorporating the HHI and HMO penetration variables using alternative

specifications. As shown in Panel (B), adding these two variables to the basic DID specification has

only modest effects on the estimated effects of being in the AOI. The estimated effect on total

27

Interestingly, this estimate of the effect of the illegal market allocation is higher than in the

analogous estimate of $62 from a simple dummy-variable specification [8], suggesting the latter is

biased downward rather than up.

28

See also McCluer and Starr (2013) for related results and discussion.

29

In the dummy-variable specification [8], the higher quantity of services contributes a somewhat

smaller share (43.2%) of the higher level of total spending on physician services in the AOI, ceteris

paribus.

16

spending on physician services is virtually unchanged at $82.7 (vs. $82.6 in the basic DID). The

quantity index declines from $49.0 to $44.2, while that on the price deviation moves up from $33.5 to

$38.5, so that the relative importance of the change in quantity index in the differential change in

spending in the AOI is a bit smaller (53.4% vs. 59.3%). Interestingly, controlling for whether a person

lived in the AOI, an increase in the HHI was associated with a significant increase in total costs, which

was due to a significant increase in the price deviation with no significant change in quantity. This

indicates that, at least in Wisconsin during this period, concentration per se was not associated with

increased quantity, but rather the business practices and agreements in use in the AOI. 30 The results

also show that, ceteris paribus, costs were higher in counties with relatively high HMO enrollments,

largely reflecting effects on the price deviation. This finding is more consistent with ‘market

segmentation’ than with ‘market discipline’, although in the former case we expected higher costs to

reflect higher quantity rather than higher price. Broadly, these results suggest that basic results

concerning the differential increases in prices and quantities of physicians services in the AOI are not

due to omitted competition-related variables.

Conceivably, effects of increases in the HHI on output and prices may be nonlinear: For example, it

may only be in highly concentrated markets that further concentration permits anticompetitive

increases in output. To test for this possibility, we re-estimate the previous model including a spline

for markets with HHIs above 2500, the cut-off between moderately and highly concentrated markets

in the current merger guidelines of the U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission

(2010). As shown in Panel (C), the results suggest that increases in the HHI in highly concentrated

markets have no extra effect on total annual spending on physician services, although this masks

some contrasting effects on quantities and prices. For the quantity index, increases in the HHI below

2500 are estimated to lower the quantity of services acquired by a given individual, but above 2500

further increases in concentration tend to raise it; this is consistent with the idea that overprovision of

services is not a simple function of the degree of market power, but that situations of highly

concentrated market power may encourage it. In contrast, increases in the HHI boost the pricedeviation in markets that are unconcentrated to moderately concentrated, with no further effect in

highly concentrated markets.

Finally, it has been suggested that comparing measures of spending, quantities and prices for

physician services in the AOI to the whole rest of the state of Wisconsin may be inappropriate, given

that the AOI mostly covers areas of low population density. Thus, we re-run the analysis confining the

sample to individuals in the 60 counties with a population density below 200 residents per square

mile; this reduces the sample size to 619,932 individual-year observations. As shown in Panel (D),

this has some notable effects on magnitudes of estimated coefficients. It increases the magnitude of

the differential increase in total costs in the AOI (from $82.7 to $105.7), although it leaves the

30

In fact, if the regressions are run using observations from the ROS only, the estimated effect of the

HHI is positive and significant in the regressions for total costs and the price deviation, but negative in

the regression for quantity, although the latter effect is significant at a 10% level only.

17

contribution of the quantity index to this increase in the same range (56.4%). This indicates that, if

anything, failing to confine the sample to counties with relatively low population densities causes

underestimation of the damages associated with acquiring healthcare services in the AOI, not

overstatement. In this part of the state, increases in the HHI increase both the quantity index and the

price deviation. Here too increases in HMO enrollment tend to boost total costs due a greater price

deviation, although the estimated magnitude of the effect is smaller. Altogether, the results in Table 5

confirm that results of the basic specification are robust to incorporation of additional competitionrelated variables and to other plausible changes in specification.

VI.

Conclusions

In sum, our econometric analysis indicates that, in Wisconsin in the 1988-95 period, quantities of

physician services rose more quickly in the AOI than they did elsewhere, consistent with the idea that

the reduction in competition amongst Marshfield Clinic and its co-conspirators created an environment

in which they could increase both prices and quantities of services by more than would have been

possible without the anticompetitive agreements. In our preferred difference-in-difference specification

(Panel (B) of Table B), which controls for persistent unobserved heterogeneities across areas and for

other competition-related factors, real patient costs rose by an extra $82.7 (9.9%) in the AOI between

1988 and 1995, with 53.4% of this increase associated with an extra increase in quantity. With all of

our estimates of differential increases in total costs being between $62 and $115, and estimates of the

contribution of increased quantity mostly in the 35-60% range, the magnitudes of our preferred

estimates are in the middle of these ranges. Again we underline that, although concerns that

difference-in-difference estimates of in principle may pick up differential changes in quality of care as

well as effects of illegal competitive conduct, in the present case direct review of evidence on changes

in the quality of care did not suggest any basis for concern about this potential source of bias in the

damage estimates. Taken broadly, our findings illustrate that estimates of the damages due to the

illegal market allocation that focused solely on differential increases in prices would have understated

the amount of damages by an appreciable amount.

The main implication of our findings is that, especially in cases where a service-intensive practice style

is a part of the competitive strategy of a provider accused of illegal anticompetitive conduct, methods

of damage estimation should not be based on price only, but rather should also consider whether

increased quantities of services contributed to the monetary losses experienced by consumers and

health insurers. Losses from this source are not entirely missing from the standard damage-estimation

method: Because this method multiplies the price differential due to anticompetitive behavior by the

actual quantity, and some part of the latter reflects the extra overprovision associated with this

behavior, some part of the extra quantity factors into the estimated loss. But to account for the fact

that these units would not have been bought at all under legal competitive conditions, the extra

quantity of services valued at the competitive benchmark price should also be added in. In the end, it

18

is an empirical question whether consumers and/or insurers in a given case are entitled to damages

from overprovision of services relative to what they would have bought in the absence of

anticompetitive behavior. The method of disaggregating damages from prices and quantities

presented in this paper provides a way to check.

19

Figure 1. Area of Influence (AOI)

20

Figure 2. Trends in average annual costs and contributions from quantity and price

(a)

Average annual

costs of health care services

(b)

Decomposition of

the difference between the AOI and ROS due to quantity and price

Note: Values are converted to 1995 dollars using the medical care CPI (1995=100).

21

Table 1. Chronology of Marshfield-related litigation

Year

Phase

Main issues

Main findings

1994

Original

Marshfield

case31

Jury found in favor of

the plaintiffs.

1995

Marshfield

appeal32

1997

Remand

case

1998

Blue

Cross

appeal

1997

Rozema

Class

Action

Case37

BCBS of Wisconsin and its HMO, Compcare, sued

Marshfield Clinic and its HMO, Security Health Plan, for

monopolization of physician services, price fixing and

illegally dividing markets with competitors.

Judge Posner found that managed care does not

constitute a separate market so the charge of

monopolization was not supported, but upheld the

finding of illegal division of markets. This required reestimation of damages based on this charge only.

A first expert for BCBS (John Beyer) found that

Marshfield clinic charged higher prices for given

procedures, compared to providers in a similar but

competitive part of the state. A second (Thomas

McGuire) presented econometric evidence that

Marshfield’s illegal exercise of market power increased

both prices and quantities of services in the affected

area.

Judge Posner affirmed that BCBS experts failed to

separate legal vs. illegal factors contributing to

Marshfield’s higher prices, and disagreed that quantity

increases could contribute to damages.35

A class action suit was brought against Marshfield Clinic

and other providers in Central Wisconsin for illegal

restraint of trade.38 One expert (H. E. Frech III) argued

that moral-hazard problems can lead to overprovision

of healthcare services, with anti-competitive conduct

tending to increase utilization. The expert who

computed damages (Robert Tollison) disaggregated

overcharges into price and output components.

31

Case was remanded to

district court.33

Judge Crabb found

McGuire’s model lacked

precedent and failed to

separate legal vs. illegal

factors in Marshfield’s

higher prices. Summary

judgment was granted

in Marshfield’s favor.34

The lower court’s

opinion was largely

upheld.36

Judge Crabb declined to

grant summary

judgment, writing that

evidence was sufficient

for a reasonable jury to

conclude that the

defendants exercised

market power in the

area of influence.39 The

case was subsequently

settled.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield United of Wisconsin v. Marshfield Clinic 883 F.Supp. 1247 (W.D. Wis.

1995). Formally, the suit was a Section 2 monopolization charge combined with Section 1 price-fixing and

division-of-markets charges.

32

Appeal to the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals. (65 F.3d 1406 (7th Cir. 1995)).

33

65 F.3d 1406, 1416 (7th Cir.1995).

34

980 F. Supp. 1298 (W.D. Wis. 1997). The initial order of April 1, 1997, was revised on April 8 and filed

on April 14.

35

McCluer and Starr (2013) discuss issues that arose in interpreting results from McGuire’s model, which

was based on a difference-in-difference approach.

36

152 F.3d 588 (7th Cir. 1998).

37

Rozema, et al v. Marshfield Clinic, Security Health Plan of Wisconsin, Inc., North Central Health

Protection Plan, and Rhinelander Medical Center, S.C., 977 F. Supp. 1362 (W.D. Wis. 1997).

38

Formally, the charges fell under the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1, and Wis. Stat. §§ 133.03 and 133.14.

39

See Associated Press (1997).

22

Table 2. Trends in average total annual charges, quantities and prices, in constant 1995 dollars

Inside AOI

Rest of state (ROS)

Difference (AOI-ROS)

Year

All years

888

875

12

844

845

-1

44

30

13

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

Change

1988-95

672

707

772

859

958

979

1,025

1,052

380

686

708

766

841

936

955

1,004

1,031

345

-14

-2

6

18

23

24

20

22

36

730

756

769

806

859

905

920

988

258

747

764

773

803

863

903

913

976

229

-17

-8

-4

3

-3

3

7

13

30

-58

-49

3

53

99

74

105

64

122

-61

-56

-7

37

73

52

92

55

116

3

6

10

15

26

21

13

9

6

Note:

= total real annual costs in 1995 dollars.

Figures may not sum precisely due to rounding.

= quantity index.

= price deviation.

23

Table 3. Variable names and definitions

Variable name

Competition-related variables

Area of Influence (AOI)

HHI

HMO enrollment

Definition

=1 if individual lives in Clark, Lincoln, Marathon, Oneida, Portage,

Price, Taylor, or Wood county; 0 otherwise

Herfindahl-Hirshman index for the county, computed from billingprovider events in the given year

Enrollment in health maintenance organizations (excluding HMOS

participating in the illegal market division), as a share of the

county’s population

Individual characteristics

Age

Female

Single subscriber (omitted)

Married subscriber

Spouse of subscriber

Other dependant of subscriber

Plan types:

Indemnity (omitted)

Administrative services only

Cost-Plus Contracts

Federal Employee Program

National Programs

High Insurance Risk Sharing

Other BCBS plans

County characteristics*

High school and over

Age in years (entered into the regression in age categories

interacted with gender)

=1 if individual is female; 0 otherwise

=1 if individual is single subscriber; 0 otherwise

=1 if individual is married subscriber; 0 otherwise

=1 if individual is spouse of subscriber; 0 otherwise

=1 if individual is other dependant of subscriber; 0 otherwise

Dummy variables equal to 1 if plan is of the relevant type

Traditional indemnity plan offered by Wisconsin BCBS

BCBS receives fixed rate to administer claims for another insurer

Plans administered by BCBS that reimburse providers for their

costs plus a specified margin

BCBS plan offered to Federal Employees

Other traditional BCBS indemnity plans based elsewhere

State-organized plan offering insurance to people unable to

obtain coverage due to preexisting conditions

BCBS plans other than those listed above

Share of persons aged 25 years or more having a high school

diploma or more

Population density

County population divided by the county’s area in square miles.

Unemployment rate

Unemployed persons as a share of the civilian labor force

Personal income per capita

Personal income per capita in thousands of 1995 dollars (deflated

using the consumer price index for all urban consumers)

Medical assist per capita

Real medical assistance per capita in thousands of 1995 dollars

(deflated using the consumer price index for medical care)

Birth rate

Births per 100,000 residents. From U.S. Census Bureau, County

and City Data Book

Death rate

Deaths per 100,000 residents. From U.S. Census Bureau, County

and City Data Book

* Data are taken from the Area Resource File (2004) unless otherwise noted.

24

Table 4. Basic regression: Difference-in-difference specification

Total annual costs

Quantity index

Coeff.

Individual characteristics

Male in age range:

5-17 years

18-24

25-34

35-44

45-54

55-64

Female in age range:

Under 5 years

5-17

18-24

25-34

35-44

45-54

55-64

Married subscriber

Spouse of subscriber

Other dependant of subscriber

Plan type:

Administrative Services Only

Cost-Plus Contracts

Federal Employee Program

National Programs

High Insurance Risk Sharing

Other BCBS plans

County characteristics

High school and over

Population density

Unemployment rate

Personal income per capita

Medical assist per capita

Birth rate

Death rate

Year dummies allowed to differ

between AOI and ROS

Δ from 1988-95 in the AOI

Δ from 1988-95 in the ROS

Difference-in-difference: AOI-ROS

s.e.

Coeff.

s.e.

Price deviation

Coeff.

s.e.

-138.4*

4.95

-141.4*

4.85

3.0*

0.51

-30.4*

-2.2

147.0*

521.9*

1163.4*

7.36

8.16

8.33

10.24

13.32

-40.1*

-22.2*

126.1*

498.4*

1137.5*

7.25

8.01

8.20

10.07

13.05

9.7*

20.0*

20.9*

23.6*

25.9*

0.78

0.99

1.02

1.20

1.79

-88.3*

-145.5*

101.7*

350.5*

329.3*

496.9*

768.7*

-50.9*

-96.4*

-113.6*

5.94

4.98

6.07

7.67

7.95

8.88

10.38

12.95

13.08

13.27

-87.6*

-148.8*

91.5*

332.5*

307.8*

475.5*

749.8*

-48.4*

-94.1*

-127.2*

5.80

4.87

5.96

7.54

7.81

8.72

10.21

12.59

12.71

12.91

-0.7

3.3*

10.2*

18.0*

21.4*

21.4*

18.8*

-2.4

-2.4

13.6*

0.61

0.52

0.77

0.97

0.99

1.09

1.25

1.66

1.67

1.70

5.4

-10.0+

611.6*

-117.6*

1489.0*

-58.0*

4.31

5.64

19.92

6.92

44.16

3.76

11.1*

-10.9*

578.0*

-105.7*

1451.5*

-66.5*

4.24

5.59

19.39

6.82

42.71

3.68

-5.6*

0.9

33.6*

-12.0*

37.4*

8.5*

0.57

0.75

2.46

0.97

5.88

0.47

-292.8*

0.017*

5.9*

11.5*

21.2*

5.8

14.7

Yes

91.79

0.003

2.26

1.18

10.57

17.64

17.58

-141.9

0.008*

5.8*

7.6*

-1.8

25.0

25.3

Yes

89.97

0.003

2.26

1.15

10.49

17.39

17.37

-150.8*

0.009*

0.1

3.9*

22.9*

-19.2*

-10.6*

Yes

313.6*

21.71

248.4*

20.70

65.2*

2.62

231.0*

8.41

199.4*

8.30

31.6*

1.16

82.6*

20.89

49.0*

19.86

33.6*

2.52

11.96

0.001

0.32

0.15

1.44

2.55

2.31

Intercept

334.9*

58.98

435.3*

57.92

-100.4*

7.76

Adj. R-squared

0.0406

0.0413

0.006

Mean of dep. variable

831.7

830.8

0.862

Notes: *= significant at a 5% level or better. += significant at 10% level or better. n=2,261,766.

Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors in parentheses. The omitted age/gender category is

male under 5 years.

25

Table 5. Estimated effects of competition-related variables: Alternative specifications

Total annual costs

Coeff.

s.e.

Quantity index

Coeff.

s.e.

Price deviation

Coeff.

s.e.

(A) Basic difference-in-difference

Differential increase in the AOI,

1988-95

82.6*

20.89

49.0*

19.86

33.6*

2.52

82.7*

21.24

44.2*

20.22

38.5*

2.58

0.009*

120.7*

0.002

17.63

0.002

17.12

0.007*

133.9*

0.002

2.37

83.9*

21.28

47.5*

20.26

36.2*

2.59

0.006+

0.006

119.9*

0.003

0.006

17.62

-0.007*

0.019*

-15.6

0.003

0.005

17.13

0.013*

-0.013*

135.5*

0.001

0.001

2.38

105.7*

23.93

59.57*

22.95

46.17*

2.99

0.011*

66.2+

0.003

36.47

0.007*

-36.02

0.003

35.80

0.004*

102.26*

0.001

5.09

(b) Adding HHI and HMO enrollment

Differential increase for the AOI,

1988 vs. 1995

HHI

HMO enrollment

0.002

-13.2

(C) Adding HHI with a spline for

HHI>2500, and HMO enrollment

Differential increase for the AOI,

1988-95

HHI

(HHI>2500)*HHI

HMO enrollment

(D) Adding HHI and HMO enrollment,

confining analysis to counties with

pop. density<200/sq. mi.

Differential increase for the AOI,

1988 vs. 1995

HHI

HMO enrollment

Notes: *= significant at a 5% level or better. += significant at 10% level or better. All regressions

include individual and county-level characteristics as explanatory variables. The number of

observations is 2,261,766 in specifications (A)-(C) and 619,932 in (D). Heteroskedasticity-robust

standard errors in parentheses.

26

References

Abadie, Alberto (2005) Semiparametric difference-in-difference estimators, Review of Economic

Studies, 72(1): 1-19.

Alemayehu, Berhanu and Kenneth E Warner (2004) The Lifetime Distribution of Health Care Costs,

Health Services Research, 39(3): 627–642.

Allard, Marie, Pierre Thomas Leger, and Lise Rochaix (2009). "Provider Competition in a Dynamic

Setting." Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 18(2): 457-486.

American Bar Association (1996) Proving Antitrust Damages (Chicago, IL: American Bar Association).

Aizcorbe, Ana and Nicole Nestoriak (2011). “Changing Mix of Medical Care Services: Stylized Facts and

Implications for Price Indexes.” Journal of Health Economics, 30(3): 568–574.

Area Resource File (ARF) (2004) US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and

Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, Rockville, MD.

Associated Press (1997) Marshfield Clinic to pay $4 million under settlement, Milwaukee Journal

Sentinel (Oct. 25): 2D.

Baker, Laurence (1994) Does Competition from HMOs Affect Fee-For-Service Physicians? NBER

Working Paper No. 4920.

Baker, Laurence and Kenneth S. Corts (1995) The Effects of HMOs on Conventional Insurance

Premiums: Theory and Evidence. NBER Working Paper No. 5356.

Berndt, Ernst, David M. Cutler, Richard Frank, Zvi Griliches, Joseph P. Newhouse, and Jack E. Triplett

(2001). Price Indexes for Medical Care Goods and Services: An Overview of Measurement Issues. In

David Cutler and Ernst Bernt, eds., Medical Care Output and Productivity, pp. 141-200. (Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press for the NBER).

Blair, Roger D. and James M. Fesmire (1994) The Resale Price Maintenance Policy Dilemma, Southern

Economic Journal, 60: 1043-7.

Bork, Robert H. (1978) The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War With Itself (New York: Free Press).

Capps, Cory, David Dranove, and Mark Satterthwaite (2003). Competition and Market Power in Option

Demand Markets. RAND Journal of Economics, 34(4): 737-763.

Cohen, Sheldon (2004) Social relationships and health, American Psychologist, Nov.: 678-684

Comanor, William S. (1985) Vertical Price-Fixing, Vertical Market Restriction, and the New Antitrust

Policy, Harvard Law Review, 98: 983-1002.

Coombs, Jan G., (2005) Rise and Fall of HMOs: An American Health Care Revolution (Madison, WI:

University of Wisconsin Press).

Easterbrook, Frank H. (1984) The Limits of Antitrust, Texas Law Review, 63(1): 1-40.

Emanuel, Ezekiel and Victor Fuchs (2008) The Perfect Storm of Overutilization, Journal of the

American Medical Association, 299(23): 2789-2791.

27

Feldstein, Martin (1973) The Welfare Loss of Excess Health Insurance, Journal of Political Economy,

81(2): 251-280.

Frech III, H.E., James Langenfeld and R. Forrest McCluer (2004) The Sensitivity of Elzinga-Hogarty

Tests and Alternative Approaches for Market Share Calculations in Hospital Markets, Antitrust Law

Journal, 71(3): 921-947.

Gaynor, Martin (2006) What do we know about competition and quality in health care markets? NBER

Working Paper No. 12301.

Gaynor, Martin, and William Vogt (2000) Antitrust and Competition in Health Care Markets. In A. J.

Culyer and J. P. Newhouse, eds., Handbook of Health Economics, Vol. 1B, pp. 1460-1487

(Amsterdam: North Holland).

Greenberg, Warren. (1998) Marshfield Clinic, Physician Networks, and the Exercise of Market Power,

Health Services Research, 33(5):1461-1476.

Grossman, Michael (2000) The Human Capital Model. In A.J. Culyer and J.P. Newhouse, eds.,

Handbook of Health Economics, Vol. 1, pp. 348-408 (Amsterdam: North Holland).

Haas-Wilson, Deborah (2003) Managed Care and Monopoly Power: The Antitrust Challenge.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Haas-Wilson, Deborah and Martin Gaynor (1998) Increasing consolidation in healthcare markets: What

are the antitrust policy implications? Health Services Research, 33(5): 1403-1419.

Hammer, Peter J., and William M. Sage (2002) Antitrust, Health Care Quality, and the Courts,

Columbia Law Review, 103(3): 545-649.

Ho, Katherine (2009) Insurer-Provider Networks in the Medical Care Market, American Economic

Review, 99(1): 393-430.

Iverson, Tor and Albert Ching-to Ma (2011) Market conditions and general practitioners’ referrals,

International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics, 11(4): 245-265.

Landes, William M. and Richard A. Posner (1981) Market Power in Antitrust Cases, Harvard Law

Review, 94(5): 937-996.

Lynk, William J. (1995) Non-Profit Hospital Mergers and the Exercise of Market Power, Journal of Law

and Economics, 38(2): 437-462.

Ma, Ching-To Albert and Thomas G. McGuire (2002) Network Incentives in Managed Health Care,

Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 11(1): 1-35.

McCluer, R. Forrest and Martha A. Starr (2013) Using Difference in Differences to Estimate Damages

in Healthcare Antitrust: A Case Study of Marshfield Clinic, International Journal of the Economics of

Business, 20(3): 447-469.

McCrary, Justin and Daniel L. Rubinfeld (2010) Measuring Benchmark Damages in Antitrust Litigation,

Paper presented in DG comp economist workshop October, 2010. Accessed electronically at

http://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/actionsdamages/rubinfeld_mccrary.pdf, 12/12/2013.

McGuire, Thomas G. (2000) Physician Agency. In A. J. Culyer and J. P. Newhouse, eds., Handbook of

Health Economics, Vol. 1A, 461-536 (Amsterdam: North Holland).

Office of the Commissioner of Insurance, State of Wisconsin (various years) Wisconsin Insurance

Report, Wisconsin Market Shares, Table E. State of Wisconsin.

28

Parker-Pope, Tara (2010) Is marriage good for your health? New York Times Magazine (April 18), p.

46.

Pauly, Mark (1986) Taxation, Health Insurance, and Market Failure in the Medical Economy, Journal of

Economic Literature, 24(2): 629-675.

Rey, Patrick and Jean Tirole (2007) A Primer on Foreclosure. In Mark Armstrong and Rob Porter, eds.,

Handbook of Industrial Organization, Vol. 3, pp. 2145-2220 (Amsterdam: North Holland).

Robinson, James C. (2001) Theory and Practice in the Design of Physician Payment Incentives,

Milbank Quarterly, 79(2): 149-177.

Rubinfeld, Daniel (2010) Econometric Issues in Antitrust Analysis, Journal of Institutional and

Theoretical Economics, 66(1): 62-77.

Ruhm, Christopher (2000) Are Recessions Good For Your Health? Quarterly Journal of Economics,

115(2): 617-650.

Sage, William (1997) Judge Posner's RFP: Antitrust Law and Managed Care, Health Affairs 16(6): 4461.

Salop, Steven C. (2005) Anticompetitive Overbuying by Power Buyers, Antitrust Law Journal, 72: 669715.

Schmidt, Donald R. (1999) Evolving Relevant Market Concepts: Product Market. In Douglas Ross, ed.,

Antitrust and health care: insights into analysis and enforcement, pp. 99-118. (Chicago, IL: American

Bar Association).

Schneider, John, Pengxiang Li, Donald Klepser, N. Andrew Peterson, Timothy Brown and Richard

Scheffler (2008) The effect of physician and health plan market concentration on prices in commercial

health insurance markets, International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics, 8(1): 13-26.

Town, Robert and Gregory Vistnes (2001) Hospital Competition in HMO Networks, Journal of Health

Economics, 20(5):733-752.

Troupis, James R. (1995). The Marshfield Clinic Case: A Primer in Conspiracy, Antitrust Healthcare

Chronicle, 9(3): 2.

U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (2010). Horizontal Merger Guidelines (Aug.

19). Accessed electronically at <http://www.justice.gov/atr/public/guidelines/hmg-2010.html#5c

on>, on 4/27/2013.

Vogt, William and Robert Town (2006) How has hospital consolidation affected price and quality of

hospital care? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Synthesis Project Issue No. 9 (Feb.).

http://www.rwjf.org/pr/product.jsp?id=15231

Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau (2007) Wisconsin Blue Book. (Madison, WI: Joint Committee

on Legislative Organization).