Dial ‘Mobile’ for Monitoring: Using Technology to Increase Sisir Debnath

advertisement

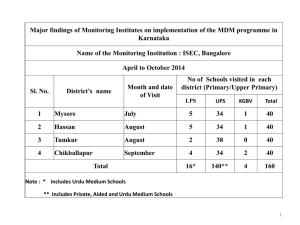

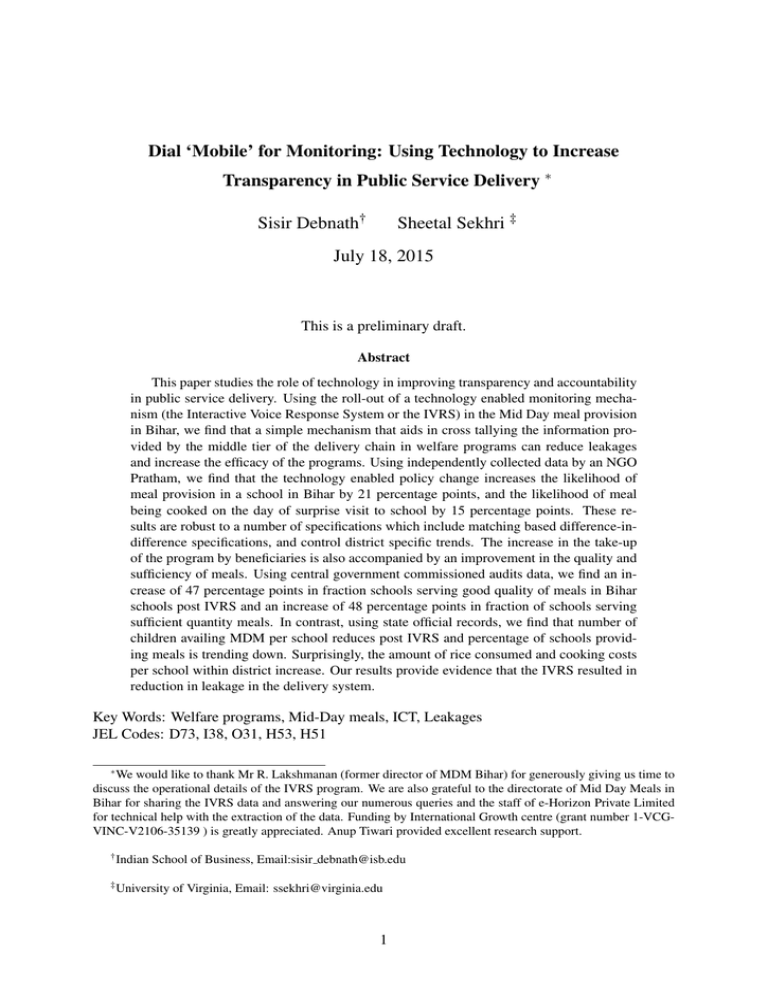

Dial ‘Mobile’ for Monitoring: Using Technology to Increase Transparency in Public Service Delivery ∗ Sisir Debnath† Sheetal Sekhri ‡ July 18, 2015 This is a preliminary draft. Abstract This paper studies the role of technology in improving transparency and accountability in public service delivery. Using the roll-out of a technology enabled monitoring mechanism (the Interactive Voice Response System or the IVRS) in the Mid Day meal provision in Bihar, we find that a simple mechanism that aids in cross tallying the information provided by the middle tier of the delivery chain in welfare programs can reduce leakages and increase the efficacy of the programs. Using independently collected data by an NGO Pratham, we find that the technology enabled policy change increases the likelihood of meal provision in a school in Bihar by 21 percentage points, and the likelihood of meal being cooked on the day of surprise visit to school by 15 percentage points. These results are robust to a number of specifications which include matching based difference-indifference specifications, and control district specific trends. The increase in the take-up of the program by beneficiaries is also accompanied by an improvement in the quality and sufficiency of meals. Using central government commissioned audits data, we find an increase of 47 percentage points in fraction schools serving good quality of meals in Bihar schools post IVRS and an increase of 48 percentage points in fraction of schools serving sufficient quantity meals. In contrast, using state official records, we find that number of children availing MDM per school reduces post IVRS and percentage of schools providing meals is trending down. Surprisingly, the amount of rice consumed and cooking costs per school within district increase. Our results provide evidence that the IVRS resulted in reduction in leakage in the delivery system. Key Words: Welfare programs, Mid-Day meals, ICT, Leakages JEL Codes: D73, I38, O31, H53, H51 ∗ We would like to thank Mr R. Lakshmanan (former director of MDM Bihar) for generously giving us time to discuss the operational details of the IVRS program. We are also grateful to the directorate of Mid Day Meals in Bihar for sharing the IVRS data and answering our numerous queries and the staff of e-Horizon Private Limited for technical help with the extraction of the data. Funding by International Growth centre (grant number 1-VCGVINC-V2106-35139 ) is greatly appreciated. Anup Tiwari provided excellent research support. † Indian School of Business, Email:sisir debnath@isb.edu ‡ University of Virginia, Email: ssekhri@virginia.edu 1 1 Introduction Social welfare programs in developing countries are infamous for poor administration and “leakages” from the distribution networks. Large swathes of benefits do not reach the intended beneficiaries (World Bank, 2003). In many countries, institutional capacity to implement safety net programs successfully is diminutive to the point of being deemed “failing” (Pritchett, 2009). Development outcomes tied to the public institutions that deliver them are undermined as a result of this failing. Yet, there is little empirical evidence uncovering what can improve the efficacy of public service delivery and importantly, reduce leakages in the delivery system. Finding low cost ways in which social program implementation can be improved remains an important constraint in improving development outcomes. Devolving the power of the government machinery by contracting delivery to private vendors (Galiani et al., 2005), involving NGOs in distribution (Bloom at el, 2006), encouraging community participation in monitoring (Björkman and Svensson, 2009) and incentivizing public delivery agents (Debnath, 2014) have been demonstrated as effective strategies in certain contexts. But these approaches are not policy-driven mechanisms that strengthen the public institutions so delivery can be improved across a broad range of services. In this study, we focus on a state driven technology enabled reform and show that information and communication technologies (ICT)can be harnessed to improve transparency and accountability in public delivery systems. We demonstrate that technology enabled improvements in delivery system enhance the efficacy of the system leading to significant increase in the delivery to the beneficiaries. Our paper uses the statewide roll-out of Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) introduced by the state of Bihar in India to improve the functioning of the Mid Day Meal Program to establish that ICT technologies can improve service delivery in developing countries. Even though India is one of the top three global producers for wheat, rice, and pulses, the incidence of malnutrition among children in India is very high. By one estimate, India accounted for 40 percent of malnourished children in the world (von Braun, Ruel, and Gulati, 2008). In order to combat mal-nutrition, the Indian government launched the National Program of Nutritional Support to Primary Education (popularly known as the Mid-day Meal or MDM Scheme) in 1995. The scheme entitles each enrolled child to a meal on the school premises each school day. The program currently benefits 120 million primary school children across the country making it one of the largest school feeding programs in the world (Ministry of Human Resource Development, India). However, this program is fraught with corruption and inefficiencies.1 Improving the effectiveness of this program can potentially induce better nutritional and educational outcomes for children.2 A key challenge faced by the top tier administration is that they have to rely on the take-up estimates provided by the middle level delivery machin1 See for example http://www.dnaindia.com/india/1866691/comment-lack-of-monitoring-corruption-plaguemid-day-meal-scheme 2 Figlio and Winicki (2005) show that improving accountability in US schools leads to better nutritional outcomes. But this study does not address how best to improve accountability. 2 ery to determine the future allocations and performance of the program. This leaves room for rigging the statistics, siphoning off from the system, and inaction or shirking by the middle tier monitors of the system. As a result, a first order policy goal is to ascertain how to improve information flow from the grass root level to the top tier. To this end, in 2012 the state of Bihar side lined take-up information provision by middle tier of the delivery machinery and introduced a fully automated platform that calls the school teachers in every school every day to record whether the meal was provided by the school. There are two ways in which this system can curtail leakages and improve the efficacy of the delivery system. First, the IVRS provides a way to cross tally information provided by the middle tier of the distribution system. Second, since beneficiary take-up information is available at much disaggregated level under the new system, it is possible to identify the schools that are not providing meals consistently. The middle tier bureaucrats are then held accountable for the performance of the school there by inducing them to increase their effort to implement the MDM effectively. We use state government reports for MDM and independent assessments of MDM by central government and an independent NGO that monitors schooling outcomes in India every year to analyze the impact of this policy reform. We utilize the introduction of the program in 2012 in Bihar and compare the outcomes in districts of Bihar to comparable districts in its neighboring states before and after the introduction of the program. We find evidence of malfeasance in reporting. As per the government data, before the program the number of children availing the MDM per school was trending upwards in Bihar and the increase was statistically significant. However, after the program there was a substantial significant decline. This event study evidence is mirrored in our Difference-in-Difference estimates using district and time fixed effects, where we find a decline in the number of children availing MDMs per school post IVRS in Bihar. Analogously, the percent of schools providing MDM also declined. In Bihar, we find over reporting of the number of schools prior to the program. In independent assessment of the program where we employ Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) data collected by Pratham, a national NGO of repute, we find significant improvement in delivery. ASER team visits 30–40 schools in a district randomly every year and assesses a number of schooling outcomes. Using this data, we find improvements in the percentage of schools providing MDM, the likelihood of whether MDM was cooked on the day of surprise visit, and the likelihood of evidence that MDM was observed in schools in Bihar over time. Our DID estimates echo these event study results and show that the percentage of schools providing MDM increased by 21 percentage points, the likelihood that MDM was cooked by 15 percentage points and the likelihood that evidence of MDM being cooked was observed by 22 percentage points all significant at conventional levels of significance. These results are robust to a number of alternate specifications including controls for school characteristics, district specific trends, and a generalized DID where we match districts based on observables before implementing the DID estimates. 3 Although government estimates show a decline in number of children availing meals per school, surprisingly, amount of rice consumed and cooking cost which includes cost of other materials added to meals increased. The delivery system that delivers MDM is also responsible for providing Vitamin A and deworming tablets in schools and periodically conducting health check-ups in schools. Although these services were not targeted by IVRS, we find evidence that provision of these services also improved after the IVRS introduction in Bihar over time. In addition, in our DID specifications, we find large and economically significant effects on these outcomes.3 Finally, we examine the effects on quality of meals using independent assessment conducted by the central government who routinely audits the schools for quality. We find that quality of good meals went up dramatically and the quality of bad meals dropped commensurately. Also, provision of sufficient quantity of meals went up and insufficient quantity meals declined in our DID specifications. Using school level administrative data and IVRS data, we find that the improvements accrue due to changes in the middle tier machinery’s operations. Using school and year fixed effects, we compare changes in MDM provision by school before and after the policy change in Bihar employing (i) annual school administrative data alone for pre- and post- policy change periods, and (ii) using administrative data for pre-period and IVRS for post period. Since, head masters reporting in these specifications is no different in the post policy period, we interpret this as evidence that head masters do not change behavior post IVRS. We also geo-referenced the administrative data of approximately 70,000 schools in Bihar and examined if the improvements in Bihar accrued in schools closer to the district head quarters and do not find evidence of such heterogeneity. This further casts doubt on changes in head masters behavior. Our paper extends two strands of literature. The first strand has focussed on establishing low cost monitoring or other mechanisms to improve the provision of public service delivery. Technology based monitoring by beneficiaries coupled with non-linear incentives has been demonstrated in inducing agents to exert effort (Duflo et al., 2012), but this mechanism may not work so well where agents can also be co-opted to steal from the system. Encouraging communities to hold service providers more accountable may improve accountability in public service provision (Björkman and Svensson, 2009). Informal networks may facilitate monitoring and enforcement (Nagavarapu and Sekhri, 2015). But when large swathes of data and information are required to facilitate such empowerment, ICT technologies can reduce costs and be useful. More importantly, we show that ICT technologies can also reduce the level of bureaucratic involvement in information flows within the systems, and thus reduce possibilities of malfeasance and shirking. Another salient contribution of our paper is to isolate a technology based policy change that can increase state capacity in delivering services. Using an experiment, Muralidharan et al (2014) show that payment infrastructures can be improved using biometric 3 In contrast, when health services were contacted out to NGOs in Cambodia, only those outcomes improved which were targeted (Bloom et al, 2006). 4 payment cards. Complementing this new evidence, our paper shows that technology can be used to design simple mechanisms that can increase state capacity to monitor agents in welfare delivery programs so that agency problems can be curtailed. Our paper also extends the burgeoning literature examining the effects of ICT enabled platforms on development outcomes. ICT enabled technologies have been demonstrated to improve producer surplus and reduce price dispersion in markets in India (Jensen, 2007; Goyal, 2010). Mobile phones have been demonstrated to increase access to credit, financial services like banking, information, and have served as reminders in health care provision.4 However, role of ICT technologies in improving transparency and public service delivery is not well established. Our study addresses this gap. Rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a background highlighting the features of the MDM program and the IVRS reform in Bihar. Section 3 discusses our data sources. In section 4, we provide a discussion of our estimation strategy. Section 6 discusses the results, and Section 7 concludes. 2 Background 2.1 MDM Program and Subsidies The National Program of Nutritional Support to Primary Education, commonly known as the Mid-Day Meal Program, was launched in India in 1995. The program entitled each school going child with a free meal each school day. Initially the program was introduced in 2,408 blocks but was extended nationwide in 1997, to cover all primary-school (grade 1 through 5) going children in government and local body public schools. The original program provided 100 grams of take home food grains per child per day including summer breaks. In September of 2004, the program transitioned from raw grains to cooked meals, that provided a minimum of 300 calories and 8-12 grams of protein per child. In 2006 the provisions under the program were changed again requiring 450 calories and 12 grams of protein per child per day with special stipulations to provide iron, folic acid, and other essential micronutrient. The 2006 revision also entailed subsidies to states for cooking and preparation costs. 5 The coverage of the program now includes upper primary classes in Government and Government aided schools. The meals are supposed to provide 700 calories and 20 grams of protein for children in upper primary grades. Under the program the central government provides free grains, while state governments are responsible for financing cooking costs. States that were unable to finance the costs were 4 Aker and Mbiti (2010) provide an excellent overview. subsidies consisted of 1.80 rupees per child per school day for States in the North Eastern Region, conditional on the state governments contributing 0.20 rupees per child per school day, and 1.50 rupees per child per school day for all other states, conditional on these other state governments contributing 0.50 rupees per school day. 5 These 5 initially allowed to distribute raw grain conditional on attendance. However, a Supreme Court judgement in 2001 mandated that all public schools must provide cooked meals within six months. In order to comply with this, the state provides subsidies to the schools in forms of financial grants. These financial grants, given to schools to provide meals, can be broadly classified as recurring and non-recurring grants. Recurring grants include cooking costs and salaries for the cooks and helpers. While non-recurring grants include infrastructure costs such as kitchen devices and kitchen sheds. These grants vary by school and are based on school level consumption. Schools estimate and report their annual requirement based on the number of students consuming meals and the number of working days. These data are aggregated at the block, district, and state levels. Based on these aggregated reports, state governments prepare an Annual Work Plan and Budget (AWP&B) and submit them to the Project Approval Board (PAB) of the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) for review and approval. Actual allocations and release of funds are based on the PAB approvals. 2.2 Monitoring and Allocation Disbursal This program is extensively monitored by states and the central government authorities. Some of the monitoring mechanisms for the implementation of the program are uniform across the states. For example the Government of India (GOI) has empaneled several Monitoring Institutes that are responsible to assess the progress and quality of the midday meal program at the district level. These institutes are required to cover 5 percent of total schools that serve midday meals in a period of two years. States submit their Quarterly Progress Reports (QPR) to the GOI that is used to assess performance. States may also have their own monitoring systems. 6 Under the system of manual monitoring, which was prevalent in India in 2012, schools submitted monthly reports to the Block Resource Person (BRP), a government functionary responsible for assisting the implementation of the mid day meal (MDM) at the block level. These reports measure the performance of the MDM provision and report the number of beneficiaries, details of meals served, and the status of funds and food grains supplied. Monthly requisitions for funds were collected by the BRPs from schools and were submitted to district offices. Based on school specific requirements, cheques were prepared manually. This entire process involved to 15-20 man days. School head masters deposited the cheques in bank accounts after receiving them from the BRPs. The process of requisitioning funds and crediting it to the schools account, took somewhere between 2 to 3 months. The monthly progress reports were not available and quarterly progress reports were compiled with a delay. Capability to take preemptive actions was also limited as monthly reports allowed only post facto analysis and could not adequately predict upcoming supply chain bottlenecks. BRPs were also required to inspect certain number of schools randomly each month 6 For example the state of Orissa has opened a control room and installed toll free telephones for students as a measure for grievance redressal. To promote compliance, all schools are also required to publicly display information on the meals and to expect periodic visits by State Government officials. 6 in order to audit the school records. However, there was no overall system for tracking number of inspections, inspections with adverse remarks that required additional action, and the status of any follow-up actions. Under manual reporting, late submission of reports by schools was typically the norm. These delays in turn led to shortage of funds and foodgrain. There was also a significant scope for siphoning both funds and food grains from this system. Data provided by the intermediary officials on the number of requisitions submitted and processed, student attendance, number of beneficiaries, number of meals served, and infrastructure provided (such as kitchen devices) were routinely inflated and reported inaccurately as there were no means to authenticate the data. 2.3 IVRS Reform The state government used the IVRS system in several ways to improve the provision of MDM in the state. First they hired district coordinators to monitor the implementation of the MDM program using the IVRS data. They are are hired on a contract basis and given an unique username and password. Coordinators periodically visit schools Bihar streamlined the requisitions and allocations by making use of an Management Information System (MIS) for the requisition and transfer of funds and food grains. The middle tier machinery of the system was still the main conduit of beneficiary take-up data to the top tier adminstration. Thus to better assess and monitor school level provision of meals on real time basis, Bihar MDM authority implemented Dopahar, an Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) that collected real time data directly from the head masters. Prior to this system, monitoring authorities had to rely on complaints by the public and audit inspections by BRPs to asses MDM performance. Although, audit inspections are supposed to cover roughly 8-9 percent of all schools, these are not conducted frequently as BRPs are severely time constrained owing to the large number of other duties. Also, it was easy to siphon off from the distribution system. As a result, figures of expenditure, beneficiaries served, number of days the school was open, and other performance indicators were not very accurate or reliable and often were inflated. IVRS was a simple technology enabled mechanism that would allow to cross tally the reports of the BRPs. Under the IVRS, each school had to register 5 points of contact (cellular numbers) including one head master, 2 teachers, and 2 para-teachers. The IVRS calls any one of the five teachers in each school at random and collects data on the numbers of meals served in each school every day. If no meals were served the teacher is supposed to press 0 and provide reason for the same. All the responses are categorical and pre-coded for the ease of data collection through mobile phones. In 2012, there were about 70,000 schools in Bihar that were supposed to serve meals to students. Table A.1 shows the cell phone penetration of the head masters collected from the ‘Dopahar’ records. Over 99 percent of the head masters had 7 a mobile phone and were contacted every day. After completing the calls to all of the schools, the IVRS system summarizes the data and generates reports at the district, block, village, and school level on attributes such as number of attendees, meals served, adherence to menu etc. The district level reports are e-mailed and sent to the District Magistrate as an SMS, while the block level reports are sent to the Block Education Officer (BEO). The mid-day meal department hires District Coordinators (DC) on a contract basis to monitor the implementation of the MDM program. They are given a unique username and password to log into the Dopahar website and monitor the implementation of the program. The system counts the number of times these coordinators log into the system during a particular period. These coordinators visit schools and check the veracity of the data. Later several add on features were added to the IVRS to increase the efficiency of data collection.7 Since IVRS collected data from all schools it was possible to identify the schools that are not providing meals consistently. The middle tier bureaucrats could be held accountable for the performance of the school inducing them to exert more effort. Dopahar data is also used to crosscheck the MIS data. It, therefore, acts as a supplement to existing monitoring systems. IVRS data is shared freely with the public through a web-interface. Thus making the headmaster’s report open to public scrutiny. Complaints or grievances from the public are recorded and followed up. 3 Data We use three primary sources of data for carrying out our analysis. The independent assessment is based on the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), carried out by an NGO Pratham to primarily collect information about the educational achievement of primary and upper primary school children in every rural district in India. Each year the survey roughly covers 570 districts, 15,000 villages, 15,000 government schools, 300,000 households and 700,000 children between 5-16. We use ASER survey data to estimate the effects of the IVRS on provision of Midday meals. These surveys are available from 2005 onward but the survey instruments are uniform and variables of interest are readily comparable for the period 2009–13. Therefore, we restrict our estimation sample to this period. Furthermore, we restrict our analysis to five states in India which are similar to the state of Bihar in terms of many socio-economic aspects and geographical proximity. Our sample includes: Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa, and Madhya Pradesh.8 The estimation sample is a representative repeated cross section at the school and household level. 7 These included miss call facility and increased call response time. If a headmaster could not receive the call from IVRS she could received it at a convenient time by dialing a particular number. 8 Uttar Pradesh is also comparable and is an immediate neighbor. We do not include Uttar Pradesh in our sample as it introduced IVRS in 2010. However, we do not have access to the government records for the state.As a result, we are not able to include it in our sample. 8 For each village surveyed under ASER, one government school (if any) is inspected randomly. For each of the inspected schools between 2009-13, ASER collected information on three vital variables: whether MDM was served in a school on the date of interview, whether the interviewer found any evidence of meals being served to the students on that day such as used utensils and meals bought from outside, and whether the interviewer found food being cooked in the school premises. Other than these observations on MDM, ASER also collects information on physical school infrastructure such as source of drinking water, provision of toilets, whether the school has a boundary wall; and questions regarding teaching staff such as the number of teacher appointed and the number of teacher present on the day of interview. The sample includes 5041 schools for Bihar and 19771 schools for the entire sample of five states. Our second dataset comes from government records. We use district level Annual Work Plan Budgets (AWPB) that are submitted by the state midday meal authorities to the Government of India for review of their performance and approval of their budget for the period 2009-13. Each state has a district wise annual target of number of children that they want to serve MDM. In addition to these targets, these reports include total number of schools serving midday meals, children availing meals, total amount of rice consumed, total amount of cooking cost, expenditure on cook’s wages. The MDM distribution channel is also responsible for school health program that distributes vitamins and deworming tablets in schools. This AWPB data also provides total number of schools and children under school health programme, total number of schools where vitamin A and deworming tablets were distributed, and total number of children who consumed vitamin A and deworming tablets. These data are provided for both primary and upper primary schools at district level. Our Bihar data has 38 districts and 189 district-year observations. Our event study analysis are based on this sample. Overall, there are 157 districts and 785 district-year observations in our sample of five states. For the health care program, we have 152 district-year observations for Bihar and 632 in the overall sample. In order to shed light on the quality of meals provided, we make use of data collected by the central government’s independent auditing of the state MDM programs. The Government of India has appointed several independent institutes to monitor the government and aided schools. Each district is assigned to one of the empaneled monitoring institutes and within a period of two years, 5 percent of the elementary schools in the district are inspected by them using surprise visits. Most of these institutes are headed by tenured professors at state universities. Post monitoring the institutes submit half yearly reports to the authorities. Apart from inspecting the daily operations of a schools, these reports assess the quality and quantity of midday meals on the day of their visit. These assessments are qualitative and the reports publish the number of schools where the quality and quantity of the meals are found to be good, satisfactory, or bad. We use these reports to create a panel dataset that entails information about fraction of the inspected schools that serve good and bad quality meals, and sufficient and insufficient quantity meals.9 We have 180 district-year observations in this sample. 9 These reports are available at http://mdm.nic.in/#. While it is possible that these data are not accurate 9 As described previously, the IVRS system in Bihar introduced in year 2012 collects data on the numbers of meals served for every school day using a technology enabled reporting system. We use this data in conjunction with another administrative data discussed below to asses the discrepancy between reporting of midday meal status by the school headmaster to the local authorities vis-a-vis IVRS.10 This data consist of information at a monthly level on number of days the system attempted to call the headmaster, number of days calls were actually received by the headmaster, attendance and number of student availing mid day meal. Using this monthly data for the period between April 2012 to November 2014 we calculate status of midday meal at the school level for the academic years 2012 to 2014, which is a binary variable taking the value one if any student availed midday meal in a school in a given academic year and zero otherwise. Finally, we also use school level administrative data from the District System for Education (DISE) reports for the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh,Orissa and Madhya Pradesh. DISE is published annually by the National University of Education Planning and Education (NUEPA). Each year the report roughly covers 662 districts, 1.4 million schools, 199.71 million students, and 7.35 millions teachers. We use this data for the period 2009 to 2013 to cross tally the status of midday meals reported by the headmasters to the IVRS and to the DISE authorities. Like with IVRS data, the status of midday meals is a binary variable taking the value one if meals are served in a school in a given academic year and zero otherwise. 4 Estimation In order to assess the effect of the IVRS on provision of midday meals, we estimate two types of empirical models. First, we use a event study framework to investigate the effects of the program on outcomes in Bihar before and after the introduction of the IVRS examining how the outcomes trend over years, and whether changes in outcomes occur precisely after the policy change. The three outcomes are: percent of schools serving meals, average number of children availing meals, and a measure of performance defined as the ratio of actual meals served against the target. The empirical model is specified as: ydt = α0 + ∑ αk × IVRS operational for k periods + αX Xdt + δd + εdt , (1) −3≤k≤1 where ydt is an outcome variable measuring provision of meals in district d in year t. IVRS operational for k periods is an indicator variable equal to one if IVRS is in effect since k years and zero otherwise. A negative value of k implies it is a pre-IVRS period. Xdt is a vector due to co-opting of monitors, these data were used to flag non-compliance and quality issues to Bihar government in 2010 preceding an accident where due to poor storage, school food rations got mixed with fertilizers and caused the death of several students who consumed the food. 10 IVRS data is obtained from e-Horizon Private Limited, the company responsible to maintain the IVRS technology in Bihar. 10 of schools characteristics at the district level.11 The specification also includes district fixed effects (δd ). We estimate equation 2 after restricting data to the state of Bihar. The parameters of interest are αk s. Second, in order to allay the concern that secular trends over time may be responsible for the changes that we are attributing to the IVRS, we estimate a difference-in-difference model. We compare the effects of the IVRS on meals provision across the districts of Bihar and control states before and after the policy change.12 The empirical model is as follows: ydt = β0 + ∑ βk × Bihar × IVRS operational for k periods + βX Xdt + δd + εdt , (2) −3≤k≤1 While other control variables remain the same as in the event study, here we interact the indicator for IVRS operational for k years with an indicator for treatment which is equal to 1 for Bihar and 0 for the other control states. Thus, the parameter of interest, βk is the treatment on treated DID estiamte which shows the effect of IVRS on outcomes in districts of Bihar after the program has been implemented. Any secular unobserved changes in outcomes are controlled for under the standard difference-in-difference identifying assumption. Our other auxiliary outcome variables, for which we estimate analogous empirical models, are rice consumed, cooking costs, cook’s wages, health checkups, distribution of vitamin A, and deworming tablets. 5 Results 5.1 Main Results We show our main results using three different datasets. The first two aid in understanding if there are any discrepancies in the assessment of beneficiary take-up based on state’s official and independently collected data. The third sample is used to determine the impact on quality metrics based on independent assessments conducted by institutes engaged by the central government. 5.1.1 Independent Data Based Assessment In Table 2, we use school level ASER data for Bihar with district fixed effects to conduct an event study analysis. In column 1, we estimate whether a school provides MDM or not. In the pre-policy years, this estimate is negligible and statistically insignificant. In 2012, there is a 17 percentage point increase in the likelihood of a school serving MDM. This effect is statistically 11 School level characteristics include fraction of schools with separate girls toilet, drinking water, playground; number of head teachers, total appointed teachers. 12 Districts are the administrative unit under the state. Our control states are in close proximity of Bihar and have a comparable poverty profile. 11 significant at the 1 percent significance level and persists in the first post policy year 2013. The pre-post comparison indicates an improvement of 18 percentage points. On a baseline average of 0.562, this is a 9.5 percent increase. This is robust to inclusion of school level controls reported in column 2.13 In column 3, we examine the effect on whether MDM was cooked on the day of the surprise visit by the survey team. Prior to the policy change, this estimate was also close to 0. This jumps to 0.19 in 2012 and and persists at 14 percentage points in 2013 both significant at the 1 percent significance level. Comparison of pre-post coefficients indicate an improvement of 12 percentage points. This is an 6 percent increase over a base of 0.503. Again, the estimates are robust to including school level controls in column 4. An analogous estimations for whether the team observed evidence of MDM served in the school on the day of the visit is presented in columns 5 and 6 without and with school level controls respectively. The results echo the previous findings. The estimates jump from nearly 0 in 2011 to around 0.20 in 2012 and 0.14 in 2013 significant at the 1 percent significance level. The pre-post comparison reveals an improvement of 10 percentage points. This is a 4 percent increase over a base of 0.425. Overall, we find consistent evidence that MDM provision in treatment schools improved after the policy was implemented.14 Next, we focus on our DID estimation and report the results in Table 3. Here, our sample includes 19,771 schools.15 Our DID estimates are remarkably similar to the event study estimates reported in Table 2. For the first outcome whether a school provides MDM or not, the estimates in column 1 indicate interaction coefficients of 0 prior to the policy change, and an 18 percentage points increase in the likelihood of serving MDM in 2012 in Bihar districts, which persists at 16 percentage points in 2013. Both these estimates are statistically significant at the 1 percent level. Results are robust to inclusion of school level controls in column 2. A pre-post difference in coefficients of 23 percentage points, on a baseline average of .562, indicates an improvement of 13 percent in the likelihood of provision of MDM in schools in Bihar. Similarly, we find evidence of an increase in the likelihood of MDM being cooked on the day of the surprise visit by the survey team in the school in districts of Bihar. Point estimates in columns 4 reveal that the interaction coefficient for 2011 is negative -0.08, statistically significant at the 10 percent significance level. Then it changes sign and is estimated to be 0.16, significant at the 1 percent significance level in 2012. Subsequently, it is 0.14 and statistically significant at the 1 percent significance level in 2013. A comparison of the interaction effects for the pre and post IVRS years indicate that the likelihood of MDM being cooked on the day of inspection increased by 20 percentage points. On a baseline of .503, this is a 10 percent increase. For whether the team observed evidence of MDM served in the school on the day of the 13 These controls include indicators for blackboards in grade 2, drinking water facilities, toilets for girls and boys, and school type fixed effects. 14 The number of observations is different in columns 1,3, and 5 because of missing values of outcome variables and further reduced in columns 2, 4, and 6 due to missing values of control variables in the data. 15 The data is a repeated cross section of schools in a district level panel data. 12 visit, as seen in columns 5 and 6, there is a negative and statistically significant trend in Bihar prior to the policy change. The 2010 interaction coefficients are -0.13 and -0.15 in columns 5 and 6 respectively (both significant at the 1 percent significance level), and the 2011 are -0.12 and -0.14, significant at conventional levels of significance. There is a change in this trend in 2012, and the interaction coefficients are now positive 0.11 and 0.08 in columns 5 and 6, significant at the 1 and 10 percent significance levels respectively. The pre-post comparison of the interaction coefficients corroborates the findings in the event study analysis reported earlier. 5.1.2 Official (State Government) Data Based Assessment We present the results of our event study, where we compare outcomes related to MDM provision before and after the policy change in Bihar, in Table 4. In column 1, the number of children availing MDM per school for primary schools was trending upwards in a statistically significant manner in 2010 and 2011 relative to 2009. In 2011, one year before the policy change, there was an increase of 57 children availing MDM per school and the estimate is statistically significant at 1 percent significance level.In 2012, the year IVRS was introduced, this was still positive but statistically indistinguishable from 0. In the first post year, this dropped precipitously to 74 fewer children per school availing MDM. The estimate is significant at the 1 percent significance level. A comparison of the pre-post coefficients reveals that on average 130 fewer children were availing meals per school one year after the IVRS was introduced. On a baseline of 353 children per school this translates to a decline of 37 percentage points. In upper primary schools (column 2), the estimates for 2010 to 2012 are small and statistically insignificant. However, in the first year after the policy change, almost 57 fewer children availed MDM per school. On a baseline of 177 children per upper primary school this was a decline of 28.5 percent. In rest of columns we turn to examining what happens to other inputs such as rice and cooking costs which include costs of other materials used in the meal preparation. Results are provided separately for primary and upper primary schools. For primary schools in column 3, rice consumed in 2010 relative to 2009 was 342.7 higher but imprecisely measured. In 2011, the estimate was -76.2 statistically indistinguishable from 0. In 2012, it was 289 but statistically insignificant. This jumped to 1182 in 2013, a year after the policy change, and is now statistically significant at 1 percent significance level. For upper primary schools, this estimate is small and statistically insignificant in the pre years and jumps to 460, significant at the 5 percent significance level. It dramatically increases to 1284, significant at 1 percent significance level in the same year when the number of children availing MDM per school decline. A prepost comparison of these coefficients indicate that consumption of rice increased by 1258 and 1180 metric tonnes at primary and upper primary schools, significant at 1 percent level. Given the baseline average consumption levels this was an increase by 52 and 117 percent. Cooking costs show a similar pattern. For primary schools, in column 5, one year before the policy 13 change the coefficient was 8.04 statistically indistinguishable from 0. One year after, in 2013 it jumped to 61.4, statistically significant at the 1 percent significance level. For upper primary schools, in column 6, the estimates are similar. In Table 5, we document the results for the DID analysis in which we use as controls, districts from 4 states from the same geographical area that have comparable poverty profile as Bihar. In column 1, we see that relative to 2009, there was a statistically significant increase of 61 in the number of children availing the MDM per school in 2011, a year before the policy change. This estimate dropped to 30 in 2012 but was still positive and statistically significant at the 5 percent significance level. In the first post year in 2013, the number dropped to 68 fewer children availing MDM per school. The coefficient is significant at the 1 percent significance level. The difference-in-difference estimate between 2011 and 2013 is 129 fewer children reported at bottom, and is significant at the one significance level. In column 2, for upper primary schools, the estimate for 2011 is 2 and statistically insignificant. This drops to -17.5 in 2012 but again statistically indistinguishable from 0. In 2013, 52 fewer children availed MDM per school, significant at 1 percent significance level. The difference-in-difference estimate between 2011 and 2013 is suggests that 54 fewer students availed MDM in Bihar, and it is precisely estimated. The rest of the columns in Table 5 show the DID estimates for other inputs used to prepare meals. The results mirror the event study evidence reported earlier. The interaction coefficient for 2011 is -12.1 for primary schools and statistically insignificant. This jumps to 670 for 2012, and 1530.6 for 2013 both significant at the 1 percent significance level. The analogous interaction coefficients for upper primary schools are -25.1 in 2011 (statistically insignificant) and 268.8 in 2012 and 1082 in 2013 both significant at conventional levels of significance. The coefficients for cooking costs increase from statistically insignificant -3.75 in 2011 to 19.3 in 2012 and 53 in 2013 both significant at the 1 percent significance level. In upper primary schools, the estimated interaction coefficient is -14 in 2011, statistically significant at 1 percent level. It dropped to -5.03 in 2012 but not distinguishable from 0, and jumped to 22.7, statistically significant at 1 percent significance level. The difference in the pre-post interactions are similar to the estimated differences in the event study analysis and they are statistically significant at 1 percent level. 5.1.3 Improvements in Other Services Using the Official Data The MDM machinery is also responsible for running another health program ongoing since 2010, where health check-ups are done for children in school, and vitamin A and deworming tablets are distributed for consumption by the school going children. IVRS did not directly target these services. By examining the impact of IVRS on the delivery of these services, we want to shed light on whether the overall system efficacy improved. In Table 6, we report the results for health check-ups, vitamin A take-up, and de-worming 14 take-up with 2010 as reference year. Specifications in columns 1, 3, and 5 control for total number of schools within each district, and 2, 4, and 6 control for enrollment in primary schools. Column 1 shows that number of schools providing health check-ups dramatically improved from 93.7 in 2011 to 1113 in 2013. Number of children who were provided health check-ups increased from 31522.2 to 88809.8. Number of schools distributing vitamin A went from -54.4 (statistically significant at the 5 percent significance level) to a positive 218.2, significant at the 1 percent significance level. Number of children receiving vitamin A went from -488 in 2011 to 78864.1. The latter estimate is statistically significant at the 1 percent significance level. The number of schools providing deworming tablets increased from 134 to 454 and and number of children receiving deworming tablets went from 21242 in 2011 to 123244 in 2013. Our DID estimates are reported in Table 7. The interaction coefficient on number of schools providing health check-ups went up from a statistically insignificant -401.2 in 2011 to 1182.3 in 2013 significant at the 5 percent significance level. The number of children who were provided health check-ups also shows such patterns although estimates are imprecisely estimated (column 2). The estimate for the interaction coefficient for children receiving vitamin A in column 3, is -26526 (statistically insignificant) in 2011 relative to 2010, but changes to 83773.1 in 2013, significant at the 10 percent significance level. In case of deworming tablets, the interaction coefficient for the number of schools for 2011 is -419.5 statistically indistinguishable from 0 but jumps to 540 for 2013 (column 4), significant at the 5 percent significance level. The interaction coefficient for number of children (reported in column 5) receiving deworming tablet went from -34844 (statistically insignificant) to 107288, significant at the 5 percent significance level. 5.1.4 Central Government Commissioned Audits Data Based Quality Assessment The quality audit data contains an unbalanced panel of districts from 2010 to 2013 for the states in our sample and has a total of 180 district year observations. Hence, we are not able to estimate an event study empirical model due to the small number of observations per year. We show our condensed DID estimates in Table 8. Fraction of schools among the audited schools that served good quality meals increased post IVRS policy change increased in Bihar relative to other states. The point estimate is 0.47 implying a 47 percentage points improvement in Bihar (column 1). The coefficient is significant at the 1 percent significance level. This is commensurate with a decline in bad quality meals. 16 In column 2, bad quality meals declined by 67 percentage points. In column 3, we report the estimate for fraction of audited schools providing sufficient quantity of meals. This went up by 48 percentage points, statistically significant at the 5 percent significance level. The fraction providing insufficient meals declined by 60 percentage points. The interaction coefficient is significant at the 1 percent significance level. 16 Since these measures in the reports are conducted from qualitatively assessments, both good and bad quality schools are reported. 15 5.2 Selection and Endogeneity Concerns One of the main empirical concerns might be that the districts of Bihar are trending differently and the results are confounded by these trends. We allay this concern for our independent assessment based results shown in Table 3 in two ways. First, we include district specific trends in our specifications. On inclusion of district specific trends, the results remain remarkably similar. Second, we match districts on observable school characteristics and estimate a generalized DID model on this sample. We provide results in Table 9. In the first panel, we show our baseline specification results condensing years into pre (2009, 2010, and 2011) and post (2012, 2013) policy change. We include a state specific trend in this specification in addition to the district and year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the district level. Additionally, we control for average district school characteristics.17 We find a 23 percentage points increase in the likelihood that the schools in the treated areas serve MDM post treatment (column 1), 29 percentage points increase in the likelihood that MDM was cooked on the day of the surprise visit (column 2), and 33 percentage points increase in the likelihood that the enumerators saw evidence of MDM being cooked in the school on the day of the visit (column 3). All three estimates are statistically significant at the 1 percent significance level. In the Panel B, we include the district specific trends. The results remain remarkably similar to the estimates reported in Panel A. In addition, we match the districts using propensity scores which we calculate using the above mentioned control variable. We trim the observations which are outside the common support of the propensity score distribution. Figure A.1 shows the relative distributions for treated (Bihar) districts and the control (other states) districts and highlights the common support. In the third panel, we restrict the sample to this common support and estimate a DID model.18 Our results, shown in the third panel, are very similar to the results documented in the first panel. In the last panel, we use a generalized DID method proposed by Heckman (reference) to estimate the treatment effect. We use a kernel based matching algorithm and employ a gaussian kernel for the procedure. We present bootstrap standard errors. Our previous results are confirmed using this specification as well. 6 Underlying Mechanisms and Alternate Hypothesis Our hypothesis is that there is less leakage from the MDM delivery machinery because the intermediate tier of the delivery system now has incentives to siphon off and shirk less. here, we investigate if the school headmasters change their reporting behavior as well. We rely on the 17 We include district level school infrastructure such as fraction of schools in a district with tap or hand-pump for drinking water, common toilet, separate toilet for boys and girls, and boundary wall; and average number of appointed teachers, teachers present during the survey as controls. 18 We show covariate balance in Table A.2. 16 fact that the head masters and the staff report the MDM provision to two different sources after the policy change but not necessarily at the same time. IVRS collects data on MDM provision every day from a randomly chosen teacher among the 5 designated teachers, and the school headmasters also manually report MDM take-up to the DISE authorities every year. We compare the effect of the policy change on MDM provision in Bihar pre and post policy change using the DISE data controlling for school and year fixed effects. Results are reported in the top panel of Table 10. There is an 11 percentage points increase in the likelihood that schools provides MDM in this sample and this is statistically significant at the 1 percent significance level (column 1). In column 2, we compare pre and post school level MDM provision in Bihar, except here we use school specific IVRS data for the post period. The effect is identical to what we reported in column 1. We infer from this that the school head masters do not change their reporting pattern after the policy change. 19 We carry out an additional test to shed light on this question. If headmasters expect more vigilance and monitoring after the policy change consonantly, change their reporting then the reporting chnage might be more pronounced in schools closer to district head quarters as these are relatively easy to physically audit. We geo-coded all 70,000 schools in Bihar and calculated their distance from the district headquarters. We then interact our post indicator with this distance measure. Bottom panel of Table 10 shows the results for the interaction effects for both the specifications used in the top panel described above. The double interaction with distance is negligible and statistically insignificant. The post indicator is identical to the top panel. Hence, results for schools closer to the district headquarters are no different than those farther from the district headquarters. 7 Future Directions We did not find any available observational data to investigate the impact of this policy reform on malnutrition or anthropometry of children. Most data sets such as the RCH focus on children between the ages of o to 5 years when they do not attend schools. There is a general need to conduct surveys which can help us to identify how nutritional status of children is changing in schools. With the help of IGC funding, we are conducting a survey to shed light on this aspect for IVRS. 8 Conclusion This paper studies the role of IT technology in improving transparency and accountability in public service delivery. We use the roll-out of a technology enabled monitoring mechanism 19 Although it is possible that school headmasters and the staff that IVRS calls keep extensive diaries so that they report consistently to each system. A very large number of headmasters would have to do this to get identical results here across samples and yet generate the improvements we observe using the ASER data. 17 (the Interactive Voice Response System or the IVRS) in the Mid Day Meal provision in Bihar, and show that a simple mechanism that aids in cross tallying the information provided by the middle tier of the delivery chain in welfare programs can reduce leakages and increase the efficacy of the programs. Using independently collected data, we find that the technology enabled policy change increases the likelihood of meal provision in a school in Bihar by 21 percentage points, and the likelihood of meal being cooked on the day of surprise visit to school by 15 percentage points. These results are robust to a number of specifications which include matching based difference-in-difference specifications, and control district specific trends. The increase in the take-up of the program by beneficiaries is also accompanied by an improvement in the quality and sufficiency of meals. Using central government commissioned audits data, we find an increase of 47 percentage points in fraction schools serving good quality of meals in Bihar schools post IVRS and an increase of 48 percentage points in fraction of schools serving sufficient quantity meals. In contrast, using state official records, we find that number of children availing MDM per school reduces post IVRS and percentage of schools providing meals is trending down. Surprisingly, the amount of rice consumed and cooking costs per school within district increase. Our results provide evidence that the IVRS resulted in reduction in leakage in the delivery system. Our findings have important policy implications. This study demonstrates that a policy driven reform initiated by a state government succeeded in improving the delivery in of a very important public service. Hence, state capacity can be increased by reforming the existing public institutions. Second, these improvements might be portable to other arenas of public service delivery which have similar delivery channels such as the public distribution system. 18 References Aker, J. C. and Mbiti, I. M. (2010). Mobile phones and economic development in africa. Björkman, M. and Svensson, J. (2009). Power to the people: Evidence from a randomized field experiment on community-based monitoring in uganda. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(2):735–769. Duflo, E., Hanna, R., and Ryan, S. P. (2012). Incentives work: Getting teachers to come to school. American Economic Review, 102(4):1241–78. Figlio, D. N. and Winicki, J. (2005). Food for thought: the effects of school accountability plans on school nutrition. Journal of Public Economics, 89(23):381 – 394. Galiani, S., Gertler, P., and Schargrodsky, E. (2005). Water for Life: The Impact of the Privatization of Water Services on Child Mortality. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1):83–120. Goyal, A. (2010). Information, direct access to farmers, and rural market performance in central india. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(3):22–45. Jensen, R. (2007). The digital provide: Information (technology), market performance, and welfare in the south indian fisheries sector. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3):879–924. Nagavarapu, S. and Sekhri, S. (2015). Informal monitoring and enforcement mechanisms in public service delivery: Evidence from the public distribution system in india. Journal of Development Economics, 111. Pritchett, L. (2009). Is India a Flailing State?: Detours on the Four Lane Highway to Modernization. Technical report. 19 FIGURE 1: Percentage of Primary Schools Serving Mid-Day Meals. Average Provision of Mid-Day Meals 1 .75 .5 .25 2009 2010 2011 Year Bihar 2012 2013 Other States Notes: We use school level data from the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) for the years 2009–13. Other states include Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and Chhattisgarh. 20 TABLE 1: Summary Statistics Bihar Obs All states Mean S.D. Obs Mean 329.86 165.83 2761.03 1311.24 82.37 40.66 417.83 38682.31 92.04 19082.27 247.11 43128.94 78.13 67.25 1345.87 800.89 43.38 26.24 858.32 83445.68 186.71 62615.61 487.28 99892.44 785 785 668 668 785 781 789 789 789 789 789 789 146.48 96.41 1898.54 1096.59 62.73 36.56 940.81 70803.31 631.80 29478.30 737.47 41069.79 S.D. Panel A: AWPB Data. Children Availing MDM per School (Primary) Children Availing MDM per School (Upper Primary) Rice Consumed Primary (MTs) Rice Consumed Upper Primary (MTs) Cooking exp. Primary Cooking exp. Upper Primary Schools under Health Check -ups Childrens under Health Check -ups Schools Distributed Vitamin A Childrens Consumed Vitamin A Schools Distributed Deworming tablets Childrens consumed Deworming tablets 189 189 189 189 189 185 190 190 190 190 190 190 115.35 58.12 1280.78 774.53 34.81 22.21 1329.94 106954.92 2908.37 74343.83 1083.52 78969.68 Panel B: ASER School Level Data. School provides meals MDM cooked MDM observed Tap or handpump for drinking water No. of Teachers appointed No. of Teachers present Common toilet in the school Separate boys toilet in the school Separate girls toilet in the school School has boundary wall 5041 5009 4882 5083 3847 3847 4031 4185 4299 5034 0.64 0.56 0.50 0.92 2.92 2.38 0.55 0.61 0.64 0.48 0.48 0.50 0.50 0.27 2.91 2.33 0.50 0.49 0.48 0.50 19771 19587 19064 20009 14663 14663 16015 16429 16742 19764 0.84 0.74 0.66 0.88 2.68 2.23 0.51 0.60 0.63 0.41 0.37 0.44 0.47 0.33 2.59 2.12 0.50 0.49 0.48 0.49 Notes:District level annual data used for Panel A and Panel B for the years 2009–13. ASER school and household survey used for Panel C and Panel D for the year 2009-13. Other states include Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and Chhattisgarh. 21 TABLE 2: Effect of Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) on Mid Day Meal provision in Schools in Bihar using ASER Data Dependent Var. Baseline average MDM Cooked School Provides Meal MDM Observed .562 .562 .503 .503 .425 .425 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Two years before IVRS -0.0067 (0.04) -0.0058 (0.04) 0.036 (0.04) 0.049 (0.04) -0.036 (0.03) -0.053 (0.03) One year before IVRS -0.035 (0.04) -0.058 (0.04) 0.024 (0.04) 0.0051 (0.04) 0.026 (0.05) -0.0012 (0.04) IVRS year 0.17*** (0.03) 0.14*** (0.04) 0.19*** (0.04) 0.15*** (0.04) 0.20*** (0.04) 0.16*** (0.04) One year after IVRS 0.15*** (0.04) 0.10** (0.04) 0.14*** (0.05) 0.10** (0.05) 0.14*** (0.04) 0.083* (0.04) Post IVRS - Pre IVRS School Characteristics R Squared No. of Observations .18*** No 0.081 5041 .12** Yes 0.084 3896 .11** No 0.081 5009 .16*** Yes 0.089 3874 .1* No 0.078 4882 .08 Yes 0.080 3783 Notes: : We use school level data from the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) for the years 2009–13. The sample is restricted to schools in the state of Bihar. All specifications control for district fixed effects. School characteristics include indicators for black boards in grade 2, tap or handpump for drinking water, availability of toilets for boys and girls and school type fixed effects. Standard errors are robust and clustered at the district level. 22 TABLE 3: Diff-in-Diff Estimate of Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) on Mid Day Meal provision in Schools using ASER Data. Dependent Var. Baseline average School Provides Meal .562 (1) .562 (2) MDM Cooked MDM Observed .503 .503 .425 .425 (3) (4) (5) (6) Bihar × 2010 -0.023 (0.04) -0.028 (0.04) -0.057 (0.04) -0.059 (0.04) -0.13*** (0.04) -0.15*** (0.04) Bihar × 2011 -0.048 (0.04) -0.064 (0.04) -0.061 (0.04) -0.084* (0.04) -0.12** (0.05) -0.14*** (0.05) Bihar × 2012 0.18*** 0.16*** (0.04) (0.04) 0.19*** (0.05) 0.16*** (0.05) 0.11*** (0.04) 0.080* (0.04) Bihar × 2013 0.16*** 0.14*** (0.04) (0.05) 0.17*** (0.05) 0.14*** (0.05) 0.033 (0.05) -0.0047 (0.05) Post IVRS - Pre IVRS School Characteristics R Squared No. of Observations .21*** No 0.164 19771 .15** No 0.124 19587 .2*** Yes 0.130 14898 .22* No 0.098 19064 .13 Yes 0.103 14579 .23*** Yes 0.161 15016 Notes: We use school level data from the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) for the years 2009–13. The sample is restricted to schools in the states of Bihar, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Orissa. All specifications control for district and year fixed effects. School characteristics include indicators for black boards in grade 2, tap or hand pump for drinking water, availability of toilets for boys and girls, and school type fixed effects. Standard errors are robust and clustered at the district level. 23 24 35.0 (25.14) -73.9*** (23.07) -130.84*** 0.775 189 IVRS year One year after IVRS Post IVRS - Pre IVRS R Squared No. of Observations -50.5*** 0.376 189 -57.6** (23.42) -9.83 (19.83) -7.12 (24.43) 1258.56*** 0.707 189 1182.4** (462.60) 288.9 (384.62) -76.2 (225.25) 342.7 (229.16) (3) 2417.44 Primary 1179.76*** 0.747 189 1284.1*** (252.92) 460.2** (214.88) 104.3 (157.83) 75.6 (99.07) (4) 1003.52 Upper Primary Rice Consumed (in M.T.) 53.36*** 0.741 189 61.4*** (12.97) 26.5** (10.12) 8.04 (6.39) 14.6** (6.89) (5) 66.69 Primary 42*** 0.758 185 44.8*** (6.41) 15.6*** (4.80) 2.78 (4.52) -0.049 (3.46) (6) 29.37 Upper Primary Cooking Cost (in Million Rs.) Notes: District level annual data used from the Ministry of Human Resource Development for the years 2009–13. The sample is restricted to the state of Bihar. All specifications control for district level fraction of schools with separate girls toilet, drinking water, playground, number of headteachers, total appointed teachers and district fixed effects. Total number of primary/ upper primary schools in a district is obtained from the District Information System for Education (DISE). Standard errors are robust and clustered at the district level. 57.0*** (12.74) One year before IVRS -18.6 (16.51) (2) (1) 19.0*** (6.44) 176.87 Upper Primary 353.38 Primary Children Availing MDM per School Two years before IVRS Baseline average Dependent Variable TABLE 4: Effect of Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) on Mid Day Meal provision for Schools in Bihar 25 30.3** (13.73) -67.9*** (13.16) -128.68*** 0.943 785 Bihar × 2012 Bihar × 2013 Post IVRS - Pre IVRS R Squared No. of Observations -54.13*** 0.689 785 -52.2*** (17.93) -17.5 (15.99) 1.91 (21.83) 1542.73*** 0.872 668 1530.6*** (298.30) 669.9*** (205.54) -12.1 (211.75) 207.4 (240.26) (3) 2417.44 Primary 1107.13*** 0.879 668 1082.0*** (187.91) 268.8** (113.67) -25.1 (136.17) -73.3 (101.02) (4) 1003.52 Upper Primary Rice Consumed (in M.T.) 56.73*** 0.859 785 53.0*** (8.87) 19.3*** (5.62) -3.75 (5.58) 1.12 (6.79) (5) 66.69 Primary 36.65*** 0.866 781 22.7*** (6.06) -5.03 (3.47) -13.9*** (4.10) -15.4*** (3.74) (6) 29.37 Upper Primary Cooking Cost (in Million Rs.) Notes: District level annual data used from the Ministry of Human Resource Development for the years 2009–13. The sample is restricted to the states of Bihar, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Orissa. All specifications control for district level fraction of schools with separate girls toilet, drinking water, playground, number of headteachers, total appointed teachers and district and year fixed effects. Total number of primary/ upper primary schools in a district is obtained from the District Information System for Education (DISE). Standard errors are robust and clustered at the district level. 60.8*** (11.53) Bihar × 2011 -15.9 (17.91) (2) (1) 11.1 (9.17) 176.87 Upper Primary 353.38 Primary Children Availing MDM per School Bihar × 2010 Baseline average Dependent Variable TABLE 5: Diff-in-Diff Estimate of Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) on Mid Day Meal provision for Schools in Bihar 26 439.8 (344.45) 1112.9*** (244.84) 0.509 152 IVRS year One year after IVRS R Squared No. of Observations 0.372 152 88809.8*** (14280.34) 61533.1* (31910.88) 31522.2** (12705.00) (2) 0.517 152 218.2*** (60.08) -5.53 (53.48) -54.4** (25.73) (3) # Schools 8722.2 (5499.81) -488.0 (4819.45) (4) # Children 0.409 152 78864.1*** (23548.48) Vitamin A 0.402 152 450.0*** (125.62) 183.8 (193.58) 133.9*** (40.03) (5) 0.399 152 123244.1*** (20260.26) 72507.0** (33636.18) 21241.6** (9028.93) (6) Deworming Tablets # Schools # Children Notes: District level annual data used from the Ministry of Human Resource Development for the years 2010–13. The sample is restricted to the states of Bihar. All specifications control for district fixed effects and time trends. In Column (1), (3), and (5) we control for total number of schools, while in Columns (2), (4) and (6) we control for total enrollment in primary with upper primary schools. Standard Errors are robust and clustered at the district level. IVRS was introduced in Bihar in the year 2012. 93.7** (42.17) (1) Health Check-ups # Schools # Children One year before IVRS Dependent Variable TABLE 6: External Benefits of Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) 27 1182.3** (269.67) Bihar × 2013 0.430 632 68449.0 (52913.30) 18967.5 (69861.50) -48777.2 (65010.02) (2) 0.294 632 -856.6 (944.23) 59.8 (466.21) -367.9 (593.75) (3) # Schools Vitamin A 0.405 632 83773.1* (30523.46) 31078.0 (22960.93) -26526.2 (21467.04) (4) # Children 0.634 632 539.4** (162.90) 247.5 (539.54) -419.5 (436.70) (5) 0.449 632 107287.7** (25991.86) 72334.3** (20487.37) -34843.7 (33221.02) (6) Deworming Tablets # Schools # Children Notes: District level annual data used from the Ministry of Human Resource Development for the years 2010–13. The sample is restricted to states of Bihar, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Orissa. All specifications control for district and year fixed effects. In Column (1), (3), and (5) we control for total number of schools, while in Columns (2), (4) and (6) we control for total enrollment in primary with upper primary schools. Standard Errors are robust and clustered at the district level. IVRS was introduced in Bihar in the year 2012. 0.478 632 546.8 (527.14) Bihar × 2012 R Squared No. of Observations -401.2 (485.16) (1) Health Check-ups # Schools # Children Bihar × 2011 Dependent Variable TABLE 7: External Benefits of Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) TABLE 8: Effect of the Interactive Voice Response System on Meal Quality and Quantity Dependent Variable treatment R Squared No. of Observations Fraction of Schools Observed Serving Good Quality Meals (1) Bad Quality Meals (2) Sufficient Quantity Meals (3) Insufficient Quantity Meals (4) 0.47*** (0.02) -0.67*** (0.03) 0.48** (0.11) -0.60*** (0.07) 0.339 180 0.576 180 0.562 180 0.610 180 Notes: We use district level monitoring data from the Ministry of Human Resource Development for the period 2010-13. The sample is restricted to the state of Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. All specifications control for state and quarter fixed effects, district level school characteristics such as fraction of schools with toilet for boys and girls, drinking water facility, a boundary wall; and average number of teachers by gender. Standard Errors are robust and clustered at the state level. IVRS was introduced in Bihar in the year 2012. 28 TABLE 9: Robustness Check: Effect of IVRS on Mid Day Meals Dependent Var. School Provides Meal (1) MDM Cooked MDM Observed (2) (3) Panel A: Diff-in-Diff with all Districts Bihar × Post R Squared No. of Observations 0.23*** (0.05) 0.29*** (0.06) 0.33*** (0.07) 0.701 740 0.622 740 0.555 740 Panel B: Diff-in-Diff with Districts with District Specific Trends Bihar × Post R Squared No. of Observations 0.24*** (0.06) 0.29*** (0.07) 0.33*** (0.08) 0.793 740 0.739 740 0.679 740 Panel C: Diff-in-Diff with Districts on the Common Support Bihar × Post R Squared No. of Observations 0.26*** (0.06) 0.29*** (0.07) 0.33*** (0.08) 0.742 454 0.677 454 0.676 454 Panel D: Kernel based Propensity Score Matching Diff-in-Diff Bihar × Post R Squared No. of Observations 0.20*** (0.02) 0.23*** (0.03) 0.15*** (0.03) 0.507 740 0.321 740 0.254 740 Notes: We use school level data from the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) collapsed at the district level, for the years 2009–13. The sample is restricted to the states of Bihar, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa. All specifications in Panel A and B control for the variables as in Table A.1. and state specific time trends, district and year fixed effects. Standard errors are robust and clustered at the district level. In Panel C we use the gaussian kernel and the standard errors are bootstrapped. 29 TABLE 10: Heterogeneity in the Effects of IVRS by schools’s distance from District Headquarters Dependent variable MDM Status: DISE (1) MDM Status: IVRS (2) Panel A: Effect of IVRS on midday meal provision in Bihar Post IVRS 0.11*** (0.02) 0.11*** (0.02) R Squared No. of Observations 0.624 281163 0.535 281163 Panel B: Effect of IVRS on midday meal provision in Bihar by schoolss distance from District Headquarters Post IVRS 0.11*** (0.02) 0.11*** (0.02) Post × Schools closer to Dist. Hqrts. -0.0049 (0.01) -0.0018 (0.01) R Squared No. of Observations 0.624 281163 0.535 281163 Notes: We use data for the state of Bihar for academic years between 2010-11 to 2013-14. Post IVRS takes the value one for the state of Bihar after academic year 2012-13 and zero otherwise. MDM Status DISE is a binary variable measuring school level midday meal status from the DISE data while MDM Status IVRS measures the same but it is constructed using headmaster reported status of midday meal in a school from the IVRS data. Both the variables take the value one if a school provides midday meals and zero otherwise. We calculate distance of each school from the district head-quarters. dist takes the value one if the euclidian distance between the school and the district head-quarters is below the median and zero otherwise. All specifications control for school, academic year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the district level. 30 0 .2 Density .4 .6 .8 FIGURE A.1: Common Support in Predicted Probability of Use of IVRS -3 -2 Bihar -1 Predicted Use of IVRS 0 Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, M.P. and Orissa Notes: . 31 1 FIGURE A.2: School Locations and District Headquarters in Bihar Notes: District town refers to the location of the railway station of the district town. The figure plots the location of all schools (about 69,000) in the state of Bihar. 32 TABLE A.1: Percentage of Headmasters with Mobile Phones in Bihar. District Fraction of Headmasters with Mobiles Araria Arwal Aurangabad Banka Begusarai Bhagalpur Bhojpur Buxar Darbhanga Gaya Gopalganj Jamui Jehanabad Kaimur (Bhabua) Katihar Khagaria Kishanganj Lakhisarai Madhepura Madhubani Munger Muzaffarpur Nalanda Nawada Pashchim Champaran Patna Purnia Purvi Champaran Rohtas Saharsa Samastipur Saran Sheikhpura Sheohar Sitamarhi Siwan Supaul Vaishali 0.99 1 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.97 0.99 0.99 0.98 1 0.9 0.99 0.99 0.9 0.98 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 1 0.9 0.99 0.99 1 0.99 Notes: We use school level data from the Bihar Mid-Day meal Department. 33 TABLE A.2: Covariate Balance Control Districts No. of Obs. (1) Tap or hand-pump for drinking water No. of Teachers appointed No. of Teachers present Common toilet in the school Separate boys toilet in the school Separate girls toilet in the school School has boundary wall Tap or hand-pump for drinking water No. of Teachers appointed No. of Teachers present Common toilet in the school Separate boys toilet in the school Separate girls toilet in the school School has boundary wall Treatment Districts Average No. of Obs. (3) (2) Average Difference t-stat p-values (4) (5) (6) (7) 0.008 0.229 0.133 0.037 -0.004 -0.011 0.028 0.86 1.6 1.06 1.38 0.14 0.38 1.38 0.3883 0.1105 0.2887 0.1681 0.8883 0.7053 0.1689 -0.003 0.339 0.231 0.028 0.009 0 0.02 0.28 2.73 2.32 1.2 0.35 0.02 1.05 0.7772 0.0068*** 0.0210** 0.2321 0.7246 0.9865 0.2934 Panel A: Districts on the Common Support 122 0.904 80 0.912 122 2.863 80 3.092 122 2.39 80 2.523 122 0.596 80 0.633 122 0.512 80 0.508 122 0.531 80 0.521 122 0.461 80 0.489 Panel B: Propensity Score Weighted Covariate Balance 331 0.905 111 0.902 331 2.766 111 3.105 331 2.28 111 2.511 331 0.59 111 0.618 331 0.509 111 0.518 331 0.53 111 0.53 331 0.448 111 0.467 Notes: We use school level data from the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) collapsed at the district level, for the years 2009–13. The sample is restricted to the states of Bihar, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa. 34 35 0.177 67279 R Squared No. of Observations 0.179 60495 0.19*** (0.06) 4 (2) No restriction 0.284 196551 0.18*** (0.05) ≤3 (3) 0.151 33223 0.29*** (0.07) 5 (4) 0.157 30791 0.24*** (0.07) 4 (5) Below Median 0.266 104152 0.20*** (0.06) ≤3 (6) 0.202 33620 0.11 (0.16) 5 (7) 0.205 29351 -0.015 (0.15) 4 (8) Above Median 0.308 91475 0.020 (0.09) ≤3 (9) Notes: We use school and household level data from the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) for the years 2009-13. The sample is restricted to children in grade 15 in the states of Bihar,Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa enrolled in schools eligible for midday meals. All specifications control for childrens age, gender, year and district fixed effects. Standard errors are robust and clustered at the district level. 0.26*** (0.06) 5 (1) Post × Bihar Grade Baseline average mid-day meal TABLE A.3: Diff-in-Diff Estimate of Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) on Arithmetic Test using Linear Probability Model 36 0.115 67535 R Squared No. of Observations 0.127 60849 0.089 (0.06) 4 (2) No restriction 0.279 198036 0.12** (0.05) ≤3 (3) 0.097 33355 0.19*** (0.07) 5 (4) 0.112 31007 0.15* (0.08) 4 (5) Below Median 0.258 105004 0.13** (0.07) ≤3 (6) 0.132 33743 0.058 (0.12) 5 (7) 0.142 29488 -0.090 (0.14) 4 (8) Above Median 0.300 92109 -0.00032 (0.09) ≤3 (9) Notes: We use school and household level data from the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) for the years 2009–13. The sample is restricted to children in grade 15 in the states of Bihar,Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa in schools eligible for midday meals. All specifications control for childrens age, gender, year and district fixed effects. Standard errors are robust and clustered at the district level. 0.15*** (0.05) 5 (1) Post × Bihar Grade Baseline average mid-day meal TABLE A.4: Diff-in-Diff Estimate of Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) on Reading Test using Linear Probability Model