Ali Ankudowich Rebekah Garder Jaimi Inskeep Elizabeth Moran

advertisement

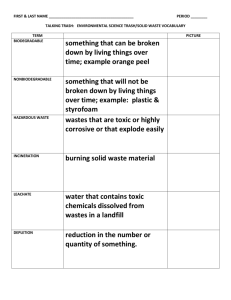

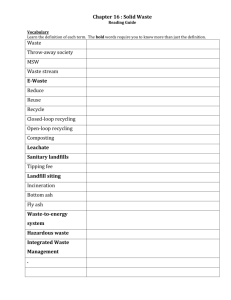

Ali Ankudowich Rebekah Garder Jaimi Inskeep Elizabeth Moran 5/8/2012 Final Draft A Turning Point for Waste Management in Northampton? I. Introduction Over the past several decades, national trends in waste management have emerged that affect the ways that the US deals with its trash. The first trend, which should come as no surprise, is that the amount of waste Americans produce is increasing. According to the EPA, in 2010 Americans produced about 250 million tons of municipal solid waste (waste that does not include construction debris or hazardous waste), an increase of about 65% since 1980 (Fig. 1) (EPA 2010). Figure 1: MSW Generation Rates from 1960-2010. (EPA 2010). Figure 2: Disposal of municipal solid waste per person per day in the U.S. (Kaufman 2009). A second trend is that the destination of the waste is also changing. In 1960, almost all municipal solid waste went to landfills (Fig. 2). Beginning in the 1980s, some waste was also combusted (Fig. 2). Combustion includes simply burning trash or burning it to produce electricity, a process that is known as waste-to-energy. Recycling showed the biggest increase out of the different disposal methods (Fig. 2). The EPA attributes this growth to market demand and increased infrastructure for recycling. According to researcher Jonathan Bloom (2010), food scraps make up 19% of the national waste stream (a figure which does not include food discarded through in-sink garbage disposals); landfilling of food doubled nationally between 1980 and 2007, and composting rates have increased little (Bloom 2010). Composting currently only represents a small proportion of waste disposal (Fig. 2). Composting food scraps reduces methane production and returns nutrients to the soil. Landfills are nationally the largest source of methane, a greenhouse gas about 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide (Bloom 2010). Methane forms when organic waste decomposes in a low-oxygen setting, such as a trash pile. Despite increases in the proportion of waste that gets “diverted” (recycled or composted), it is important to note that the amount of waste going into landfills per person per day is still similar to what it was in 1960 (Fig. 2). The final trend to note is that the size and location of landfills is changing. Across the country, the number of landfills has steadily decreased while the average size of landfills has increased, representing a trend towards consolidation (EPA 2010). The capacity of landfills in Massachusetts is expected to decline from 2 million tons to 600,000 between 2009 and 2020 (MDEP- Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs 2010). At the national level, landfill capacity “appears to be sufficient, although it is limited in some areas” (EPA 2010, p. 10). The Northampton Sanitary Landfill on Glendale Road in Northampton, Massachusetts (hereafter referred to as the Glendale Road landfill, or “Glendale”), reflects national trends in waste disposal at a local level. Glendale is a regional landfill, accepting waste from 44 municipalities in Western Massachusetts (Fig. 3). Like many landfills in the area, Glendale is nearing capacity. In 2009, citizens of Northampton voted not to expand the landfill because of environmental safety concerns (Cain 2012). Due to this decision, the Glendale landfill is expected to close in 2013, meaning that 50,000 tons of trash per year it can collect will need to be sent to other landfills (City of Northampton DPW 2009). Figure 3: Municipalities utilizing the Glendale landfill. (CCON 2007). The landfill’s imminent closure raises several questions. First of all, is it a possibility that Northampton could build a new landfill in another location? We believe that a new landfill is not the best solution from a sustainability perspective, and also that siting a new landfill would be extremely difficult given the NIMBY pressure that has built up against the current landfill. NIMBY, an important phenomenon in environmental politics, stands for “not in my backyard” and makes reference to citizens’ opposition to unappealing and sometimes high-risk facilities sited in their locality. Some view NIMBY as a “selfish unwillingness to accept the costs of one’s lifestyle” while others view it as a rational response to perceived risk or inequity (Layzer 2011, p.1). If individuals were concerned about the health risks associated with landfill expansion, it would be difficult to go through the process of finding an entirely new location that citizens would be content with. Living near a landfill is not desirable because of potential health risks, increased traffic in the area from dump trucks, and the smell of trash. Social justice concerns usually come up because wealthier areas can lobby to keep the landfill out of their neighborhood while areas of lower income either do not have the time and resources to oppose the facility or feel forced into the situation due to the potential financial benefits. Because of these NIMBY pressures and social justice concerns, siting a new landfill would be a long, difficult, and unlikely process to complete. If expansion and a new landfill are out of the question, Northampton is left with two options: to ship the waste farther away and/or reduce trash. As of May 2011, there were 24 active landfills in the state of Massachusetts, 7 of which are in the western part of the state. These landfills were located in Adams, Agawam, Chicopee, Granby, Northampton, South Hadley, and Warren. According to the most recent list of active landfills from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MDEP), the landfill in Warren closed in 2011. Along with Glendale, the waste facilities in Granby and South Hadley are also expected to close in 2012 or 2013. With these closings, only three more landfills will be open in the western part of the state. It is projected that these final three will reach capacity in 2015, 2017, and 2022 (MDEP 2011). The closure of neighboring dumps will likely lead the remaining ones to experience an increase in waste tonnage per year, causing them to fill up more quickly than expected. Some waste haulers, such as Duseau Trucking of Northampton, now ship their trash to New York State where there is more landfill space and where tipping fees (the cost for dumping one ton of trash) are cheaper. Since regional waste disposal looks tenuous, waste reduction could be an alternative. Though it would be extremely difficult to divert all waste due to the laws of entropy and the increased costs relative to benefits as diversion approaches zero, it is possible to get close. The term “zero waste” refers to a 90% or higher diversion rate, meaning 10% or less of trash ends up in a landfill or incinerator. Later in this paper, we discuss what some cities, businesses and institutions are doing to make zero waste a reality. First, however, we begin the case study of the Glendale Road Landfill by providing some of its history and the controversies surrounding it. Next, we review the economics of the Glendale landfill--an important subject for understanding what future options are viable. We then examine some of these waste disposal alternatives, focusing on zero waste, which we believe is the most sustainable option in the long term. We also explore the barriers to the implementation of zero waste in Northampton. Finally, we offer our conclusions on what steps Northampton needs to take to achieve zero waste, and we resituate the case study within the larger context of national and international waste management. II. The Historical Backdrop The history of Glendale Road sheds light on the current situation. There are two points in particular that are salient to the rejection of the most recent proposal for the expansion of the landfill. The first is the fact that Northampton has expanded the landfill several times before. The second is the fact that there has been a sustained discourse concerning pollution at the landfill throughout its history of expansions that culminated in the rejection of the most recent proposal. The past expansions of the Glendale Landfill began in the late 1980’s. According to The Daily Hampshire Gazette, many municipalities and state leaders considered the state to be in a veritable trash crisis (Pollard 1986, Stone 1987). At the time, several landfills in Massachusetts were slated to close within the decade and only a few were being built (“Garbage woes” 1987). Meanwhile, other states were hesitant to take the trash; Rhode Island even set up a special force of police cruisers to stop Boston trash haulers from crossing the border. At the same time, the cost for using the existing landfills was increasing due to tighter environmental regulations and increasing demand. The situation got to the point where trash haulers protested outside of the Department of Environmental Quality Engineering headquarters in Springfield (“Dump trucks” 1987). At this point, Northampton, along with other municipalities, had to decide what to do with the trash being produced. The more progressive long-term solutions that were available then very closely resemble those being considered today: resource recovery with waste-to-energy plants, recycling, and composting. At the time, the state was recycling about 5% of its waste and was processing 17% of its waste in waste-to-energy facilities; additionally, it had 5 composting pilot projects in operation (“Garbage woes” 1987). In the end, Northampton decided to expand its landfill, and construction of the first phase began in 1988 (“Dedham firm” 1988). The outcome of the situation in the 1980’s was the opposite of that of 2009, even though the issues and the proposed solutions were fairly similar. The evolution of the pollution discourse in the most recent expansion controversy appeared to be a game-changer in terms of whether history was to repeat itself or not. The pollution issue stems from the very inception of the landfill in 1969. At that time, according to Smith geology professor Robert Newton (2012), landfills were often created from the pits left over from sand and gravel mining. Glendale was one such landfill; waste was dumped into the pit without any form of lining. This siting practice is problematic because the sand and gravel of these pits are extremely porous. That means that leachate (rainwater contaminated from running through the landfill) could travel quite easily through the ground, posing a potential risk of groundwater contamination. The fact that the original portion of the landfill was completely unlined has also been a source of concern for decades (Newton 2012). As early as 1980, groundwater tests were run to monitor groundwater pollution. While these tests came back negative, there was still concern due to the fact that nearby Hannum Brook was showing elevated levels of iron oxide that turned the water orange (Gorenstein 1980). Concerns about the groundwater flared again with the proposed expansion in the late 1980’s due to the fact that part of the landfill would fall within 100 feet of a wetland (Oh 1987, Pollard 1988). The city had to obtain permission from the Conservation Commission to go ahead with the project. There was no opposition voiced at the Conservation Commission’s public hearing, so the city was granted approval. Additionally, there were concerns about arsenic in the water. The depletion of oxygen in the groundwater from aerobic decomposition of organics in leachate from the landfill could cause arsenic to precipitate out of surrounding rock (Newton 2012). In 2007, a study was done to assess whether or not residents living near the landfill suffered from higher rates of cancer, autism and asthma, with an emphasis on cancer (Crowley 2007). Despite the fact that a definitive causal link between the proximity to the landfill and higher incidence of cancer could not be found (Newton 2012), the perceived risk was still high and was an important factor in mobilizing citizens against the landfill. The pollution discourse came to a head with the proposal to expand the landfill further over the Barnes Aquifer, an expansion which would have covered a recharge area for Easthampton’s Maloney Well (figure 4). The part of the aquifer over which the landfill was set to expand was designated as a Zone II area, which, according to the MDEP, “contributes water to a well under the most severe pumping and recharge conditions that can be realistically anticipated (180 days of pumping at approved yield, with no recharge from precipitation)” (Mass. Drinking Water 2009). Massachusetts state regulations prohibit building a landfill over a Zone II area, but the city applied for and obtained a waiver from the state to go ahead with the expansion. Figure 4: Barnes Aquifer. From: Barnes Aquifer Protection Advisory Committee, <http://www.pvpc.org/bapac/diag_maps/aquifer_map.html> In 2007, a group calling themselves Concerned Citizens of Northampton (CCON) published a report on the Glendale controversy provocatively titled “Water Supply Protection and the Landfill: An Inconvenient Truth” (CCON 2007) referencing Al Gore’s 2007 documentary about global climate change. The document, still available online, includes an original 11-page report as well as supplemental reference materials from the MDEP and other sources. The report attempts in a political and persuasive way to persuade Northampton residents to oppose the granting of the state waiver that would allow the expansion. The CCON report represents in many ways the “narrow parochialism” that Wheeler (1994) identifies as a component of NIMBYism. For example, the authors focus heavily on a handful of studies linking landfills and human health risks, and they imply that the state was pressuring the town to expand the landfill (CCON 2007). Calling on the precautionary principle and framing the town as a victim of larger, more powerful forces are examples of why NIMBY-related rhetoric can be evocative and politically successful. In spite of some opposition, the state waiver allowing the expansion was granted, and the ensuing citizen resistance became even more pronounced. In addition to the CCON, groups such as the Barnes Aquifer Protection Advisory Committee (BAPAC) and Water Not Waste mobilized the public against the proposed expansion. A petition was organized to gather the signatures necessary to put the expansion to a ballot vote; 1,993 were collected in all. Thus, the question “Shall the City of Northampton expand the Northampton landfill over the Barnes Aquifer?” made it onto the ballot and was subsequently voted down by the citizenry in 2009 (Cain 2009a, Cain 2009b). The potential danger posed by the landfill expansion was not universally accepted; the area was considered by some as a recharge water source that would not significantly impact primary drinking supplies (Contrada 2012). Some believe that the arguments about risk used by expansion opponents may have been oversimplified. For example, many of the health studies cited were considered inconclusive by other authors (Goodman 2007). The expansion would have been double-lined and would have featured state-of-the-art engineering (Contrada 2012; Veleta 2012), possibly posing much less risk than the original, unlined portion of the landfill. However, there were concerns about the synergistic effects of the various pollutants on public health, which is to say that despite the fact that each individual pollutant might appear in small quantities that were deemed not significantly harmful, the impact of all these pollutants together could be hazardous (Odgers 2012). The crossing of a symbolic political boundary, when the state waived its environmental regulation in order to make the expansion possible, may have been what finally sparked a public outcry against any further expansion of the landfill. This outcry was fueled by so-called NIMBYism and was framed in terms of environmental and human health risk. The results of this outcry--a rejection of the expansion and the subsequent pending closure of the landfill--will have profound consequences for waste management in Northampton. One of the most important consequences will be economic effects due to the closure of Glendale. III. The Economics of the Glendale Landfill In the case of the Glendale Landfill, the city owns the facility but has contracted a private company, Solid Waste Solutions, to operate the landfill. The Glendale landfill is currently financed by the fees received from municipalities, haulers, and community members that utilize the dump. Unlike some cities, Northampton does not utilize taxes to fund municipal waste services. Thus, Northampton residents must pay for their trash out-of-pocket. They have the option of either paying for a curbside collection service or dropping off their own trash at the Locust Street transfer station or the landfill itself. For waste haulers to use the Glendale landfill, there is a $67.50 per ton tipping fee (Veleta 2012). For citizens who drop off their own trash, they must purchase a $25 per year transfer site permit. An additional fee is required for each bag thrown away based on its size. Closing the landfill already means that the city of Northampton will experience a loss in annual income. In 2011, the city made $363,400 from waste management. It is predicted that expansion would have brought in $25.4 million by 2039 (Cain 2012). Since the city will no longer be gaining revenue from other towns that use the dump and will have to pay to dispose of their trash elsewhere, the impact on the budget will be significant: the closure of Glendale is predicted to cost the city $8.3 million by 2039. Additionally, there are costs the city must face in order to properly close the site. Capping and monitoring Glendale for 30 years will cost an estimated $1.65 million and $1.95 million respectively. Additional liabilities (i.e. costs for previous expansions) will run around $2.125 million (Cain 2012). The decisions that Northampton makes regarding trash collection and disposal will alter the revenue and expenses that the city, and indirectly, the citizens, will have to face. Once the landfill is closed, the city will still get some revenue from the site. Until 2028, $35,000 per year can be gained from methane gas collection. There is currently a cell phone tower at Glendale which provides $60,000 per year for Northampton. Revenue of $25,00050,000 a year is estimated to be gained by metal recycling from transfer stations, and $40,00080,000 per year for recycling other materials (Cain 2012). The Northampton Department of Public Works (DPW) Enterprise Fund pays for a number of other municipal services, such as water treatment, in addition to the city’s waste management activities. The Fund had an annual budget of approximately 15.8 million dollars in 2010, 92% of which came from rates and fees paid by users of these services (Dwyer and Holle 2010). Because the landfill accepts waste from so many other municipalities, these “users” are not only Northampton residents; it is because of this outside source of revenue, according to David Veleta (2012) of the DPW, that the Fund is able to maintain a positive balance. The Enterprise Fund pays the salaries of DPW staff, including a full-time staff member who works on promoting waste diversion, recycling, and composting programs in the city of Northampton. According to Veleta (2012), the city’s recycling program is a cost, not a source of revenue. The city receives some money for recyclable materials when they are delivered to the recycling center in Springfield, but the costs of collecting and transporting recyclables are greater. The city has been able to keep recycling services free to Northampton residents by covering these costs under the Enterprise Fund budget. Veleta was uncertain about the future of free recycling in Northampton once the landfill closes and the sources of extra revenue for the Fund dwindle. He asserts that, without revenue from the landfill, the Fund will become a “revolving” fund, possibly breaking even--rather than carrying a positive balance--even if recycling fees are imposed. This financial situation raises serious questions about the affordability of future waste-diversion initiatives. It also raises questions of whether or not the costs of trash disposal should be passed directly on to citizens. As several interviewees have noted, citizens in Northampton--like people in many parts of the country--have gotten used to very cheap waste disposal, leading to the formation of irresponsible attitudes and behaviors regarding trash (Odgers 2012, Contrada 2012, Newton 2012). IV. Business as Usual? Or Zero Waste? Other than waste reduction, there are several options still on the table. These are wasteto-energy and shipping waste to a different landfill. Sending trash to a waste-to-energy incineration facility produces energy and saves resources traditionally used to produce energy while reducing landfill buildup. Using such a facility can reduce the amount of waste Northampton needs to send to another city’s dump. While utilizing an incineration facility can reduce the pressure on landfills, such facilities are criticized for their negative impact on air quality. Some of the pollutants that are released from this form of disposal include lead, mercury, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, and sulfuric acid. These chemicals contribute to acid rain, which has a negative effect on wildlife, rivers, soils, and infrastructure ("Alternatives to Landfill" 2005). Nevertheless, these facilities are regulated and scrubbers are used to reduce the pollution (Wieman 2012). Incineration is also criticized because ash is left over that must still be transported to a landfill; thus, the need for the landfill still exists. The cost of incineration is often disadvantageous unless energy recovery is utilized. In spite of these concerns, one potential option for waste management in the region is the Springfield Covanta incineration facility in Agawam, MA. The facility can take in 131,400 tons per year and can produce 9.4MW of electricity when running at full capacity ("Covanta Springfield, LLC." 2012). This incinerator utilizes scrubbers as well as energy recovery; the heat and steam that is produced is used to create electrical energy ("Alternatives to Landfill" 2005). According to Mr. Dombkowski (2012) at Smith College Facilities, the Springfield facility also sorts out recyclables so they can be reused and not burned along with the rest of the trash. Covanta Energy operates many additional incinerators across the U.S. The company has been cited for environmental violations at various locations. In 2008, the MDEP fined Covanta for surpassing the acceptable amount of pollutants emitted into the atmosphere. The amount of dioxins and furans exceed the limit by 350% at the Pittsfield location. The company has also experienced citations in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Zero waste, on the other hand, is a goal to create a more sustainable future where less than 10% of waste ends up in landfills and incinerators. The other 90% of material is reused, composted, or recycled (Liss 2004). It is a process that takes time to accomplish, but has been implemented and achieved by some communities, including San Francisco and Nantucket. Not only does it reduce the amount of waste to be dealt with, but it can also increase jobs within a community. It is estimated that recycling plants create twenty-five times more jobs that landfills dealing with the same amount of materials (MDEP-Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs 2010). Turning to a zero-waste initiative will reduce the amount of trash that needs to be dealt with by the municipality. With a decrease in the amount of waste going to either a landfill or an incineration facility, the potential hazardous effects of such facilities will be limited. Decreasing waste production in Northampton will reduce the amount of materials that need to be sent to other towns for disposal or incineration; this reduction will lead to a decrease in fuel usage by dump trucks and will decrease the amount of carbon dioxide entering the atmosphere. Reducing the amount of waste sitting in a landfill can also lessen the risk associated with leachate. Increasing recycling will create more starting material for products that can be used instead of spending energy to harvest raw materials. The best part of the zero-waste plan is reducing waste by reusing products, whether it is in one's own home or selling things at reuse centers or secondhand shops. By increasing the amount of use for each product, materials and energy can be saved, which eliminates an additional carbon footprint. A few trailblazing municipalities have shown that zero waste is an achievable goal. One example is Nantucket Island, located off the coast of Cape Cod. Before it took on zero waste, Nantucket saw its landfill space dwindling, and residents worried about the costs of shipping all their waste thirty miles to the mainland. Due to a strict trash management program in 2008, Nantucket has diverted 92% of its waste (Kaufman 2009). On top of recycling the usual items like cans and bottles, Nantucket mandated the recycling of more difficult objects like tires, batteries and household appliances. They also began picking up composting and taking it to a municipal composting facility. For reusable items like clothing, books, or furniture, the town set up collection sites (Becker 2009). San Francisco is also working towards zero waste. The changes in the city began in 1989 when the state of California implemented an act requiring all cities and counties to divert 25% of waste by 1995 and 50% by 2000. The state supported the development of new markets for recycled products and also required certain products like newspapers and plastic bags to contain some post-consumer recycled material (Tam 2010). San Francisco surpassed the state goal with a 72% diversion rate in 2010 (Fig. 5) (Tam 2010). In 2001, the city implemented curbside compost collection. Since 2006, multiple ordinances have been passed: recycling of construction debris, utilizing compostable or recyclable take-out containers at restaurants, and making recycling and composting mandatory. The city plans to meet zero waste standards by 2020. San Francisco attributes its success to aggressive public policy, a positive public-private partnership with the waste-hauler, and a community that understands the importance of waste diversion (Tam 2010). Northampton has shown similarities to both Nantucket and San Francisco. Like Nantucket, the Glendale landfill is nearing capacity and siting new landfills or incinerators is getting harder. Furthermore, Northampton has a relatively progressive public like San Francisco, so education and public participation might be easier than in a place where citizens were less concerned about their environmental impact. Figure 5: Waste diversion in San Francisco compared to California and the U.S. (Tam 2010). V. Can Northampton adopt zero waste? Northampton has not yet decided where it will send its own trash once Glendale closes or how it will handle municipal waste, but a city-commissioned task force composed of interested citizens, as well as a reuse committee composed of DPW employees, have both looked into the various options available (Odgers 2012; Veleta 2012). There have been discussions about whether to keep the transfer stations open and allow the use of private curbside waste collection services, have a citywide curbside pick-up service only, or use a citywide pick-up service with a transfer station opt out. Each of these scenarios has economic, social, and environmental benefits and disadvantages. Having a curbside pick-up service is more costly for citizens than using a transfer station. However, if a family or individual wants a curbside pickup service, it would cost them less to use a citywide collection service than a private service. According to Karen Bouquillion of the Northampton DPW (2012), for the citywide service to make sense financially to the city, at least 70% of residents need to utilize the service. Bouquillon is currently managing a number of waste diversion programs in the city. Household food wastes and non-recyclable paper can be dropped off at the Locust Street Transfer Station to be composted; areas of the Locust Street station have been set aside for the exchange of used clothing and books, and a variety of annual events are held to collect reusable materials such as building materials, electronics, and bicycles. The city has a popular compost bin distribution program and promotes backyard composting (Bouquillon 2012). Bouquillon also states that the DPW, and the city government more broadly, are amenable to waste diversion and even zero waste as long-term goals, but no comprehensive plan is currently in place. As the DPW task force considers its options in the face of Glendale’s closure, she anticipates the possibility of a zero-waste committee being appointed, which may be bolstered by the availability of a new EPA grant designed to assist municipalities in adopting zero waste. She considers zero waste a feasible goal for Northampton, but notes that publicity, coordination, and advocacy will all be needed. Furthermore, financial sustainability could be a barrier. The creation of a zero-waste infrastructure could theoretically have been funded by the Enterprise Fund (as many of the city’s current waste-diversion initiatives already are), but with the landfill slated to close--leading to the loss of finances for the Fund--such an infrastructure would depend initially on grants to get started. In the long run, citizens would have to pay more in user fees than they currently do for services such as recycling, but reuse and recycling services would remain cheaper than disposal. The financial viability of a city-managed system would also depend on sufficient demand, a factor that is not an issue for cities whose waste management systems are tax-funded. Indeed, Bouquillon agreed with Veleta that moving away from the use of private haulers and toward a city-wide curbside system--whether funded by a tax or by user fees-would make the development of a zero-waste system much more viable. She cited the example of San Francisco’s three-bin system. Citizens who currently save money by dropping off their own trash at the transfer station would likely resist such a change, and private haulers such as Duseau might try to undercut the city’s rates. Northampton recently implemented the SMART program (Save Money and Reduce Trash), which involves the mandatory use of official blue trash bags in different sizes for landfill disposal. Small bags cost $0.50, medium bags cost $1.00, and large bags cost $2.00 (NDPW 2011). The goal of the program is to make people more aware of the volume of trash that they produce. In the context of increasing costs, pressure to reduce waste will fall on individuals, institutions, and businesses. There are multiple options and actions that can be taken depending on the desired long-term goal, whether the desired change will occur on a small or large scale. The opportunities available to individuals and groups are also dependent upon their social and financial capital and availability. Local businesses, institutions, and schools in Northampton are already implementing their own waste reduction programs. In the absence of a widespread municipal composting program, a number of individual businesses in Northampton have begun to divert more of their food waste into compost. In 2003, as part of a project in Amherst and Northampton supported by the MDEP, 10 Northampton restaurants were diverting a combined total of over six thousand pounds of food per week into compost (CET 2003). Engaging restaurants in composting is critical if total waste is to be reduced, especially considering that Americans spend on average over 40% of their food dollars eating out (Bloom 2010). Restaurants face a number of challenges in implementing composting regimes, such as increased labor costs and the possibility of food waste odor in or around the restaurant (CET 2003). In addition to being a major part of the American diet and therefore a major contributor to the food waste stream, eating in restaurants creates extra waste due to takeout containers, napkins, and similar items. Some restaurants, such as the Northampton Brewery, make sure that compostable paper waste is collected in addition to food scraps (CET 2003). The Northampton Brewery also has a larger business philosophy of waste minimization; the owners asserted that all new staff is automatically trained in recycling and composting procedures and the composting program does not incur any extra costs (CET 2003). Two restaurants in Amherst, whose landfill had already closed at the time of the CET report, found that while labor costs may have been a barrier to composting programs in the past, the increase in trash hauling costs after the landfill closure made it economically viable to divert part of their waste into compost (CET 2003). In the long run, businesses like the Northampton Brewery, which has chosen to adopt a business philosophy that includes environmental concerns, cannot be expected to be the norm, but if trash hauling fees increase dramatically in Northampton with the landfill closure, there will be more financial incentives to motivate businesses to compost. In addition to these restaurants, Smith College, located near downtown Northampton, has also integrated systematic composting into its waste management practices. With 2,500 undergraduates on campus and numerous faculty and staff, it creates a great deal of waste that must be sent somewhere ("Smith at a Glance"). According to Mr. Dombkowski (2012) from Smith Facilities, previously 900 tons of trash were produced a year. Once the school discovered that the Glendale landfill, where they were sending their trash, was going to close, the school decided to immediately find an alternative. Administrators were concerned that larger waste collectors would force the school out of opportunities at open landfills. In 2010, Smith stopped shipping its trash to the landfill. To reduce the amount of trash that needs to be disposed, Smith dining implemented a compost program. What started out in a pilot program in three of the dining halls is now running in all eleven. As a result, 300 tons of waste is diverted during the year. The compost is sent to a farmer in Westhampton who owns a large former dairy farm. The farmer is paid $28 per ton. While Dombkowski says that there is little likelihood of implementing a zero-waste program at Smith, the target is to recycle and compost 50% of waste. The college is currently around 38% (Dombkowski 2012). The waste that Smith cannot divert is sent to the Covanta incineration facility in Agawam, MA. It costs Smith $89 per ton to bring waste to Covanta. Since it is cheaper to dispose of the compost, the compost program is financially beneficial. Northampton public schools are also utilizing the closing of the landfill and the community discussions on trash as a stepping point for waste reduction. A pilot zero waste program has been started in some of the local schools. The Jackson Street School was the first to initiate the program, then 5 more schools joined. With the program, children learn about the importance of reducing consumption and waste. Instead of just trash cans, there are recycling and compost bins for the students to use (“Green Action” 2011). Staff in the cafeteria was hesitant about the changes but found the switch to be very easy (CET 2003). Composting at the schools has diverted 40.8 tons of food from the landfill and has reduced the trash pickups from two days a week to one; this is nearly a 90% reduction in waste (“Green Action” 2011). The compost is sent to the Smith Vocational Agricultural School Farm where it is mixed with manure and other yard waste and sold as usable compost and fertilizer. The children are not only helping to reduce their waste but are learning about the importance of waste reduction. They can go home and tell their parents about the program and potentially initiate discussions within the household about the concept. Energy use reduction is an additional component of the program, one which administrators have seen immediate financial benefits from (“Green Action” 2011). Reducing waste is projected to save the schools $1,000 during the year (CET 2003). The success and spread of the program within the schooling system provides information on the logistics, feasibility, and community response to such an initiative. It has also provided a working infrastructure for other institutions. Although these individual initiatives by businesses and institutions are positive developments, there are limits to what such initiatives can achieve on a city-wide level. These same limits, of course, also apply at other levels: there are limits to what individual cities can achieve in the absence of state-level waste-reduction commitments, and so on. In our conclusion, we take a wider view of some of these issues, and then argue that, for Northampton, a municipallevel zero-waste commitment is the most far-sighted and sustainable option. VI. Conclusions The impending closure of the Glendale Road landfill could represent a turning point in how the city of Northampton approaches its waste. In a kind of “reverse NIMBYism,” David Veleta (2012) of the Northampton Department of Public Works noted that it might have been more responsible to go ahead with the expansion, so that the city of Northampton is forced to deal with its own waste. He was concerned about the possibility that merely sending trash “somewhere” else might encourage people to worry less about the environmental consequences of waste disposal. Furthermore, the Enterprise Fund revenue currently supports many waste-diversion initiatives, as we’ve discussed, and the closure of the Glendale landfill will result in a loss of that revenue. However, Veleta also acknowledged that there would be an inherent tension in keeping the landfill open while also pursuing waste-diversion initiatives: revenue from the landfill supports such initiatives, but because the revenue comes from waste that has not been “diverted” that revenue is dependent on such initiatives being less than fully successful. If too much waste is diverted, revenue dries up. If Northampton pursued a comprehensive zero-waste plan within its own borders, but kept the landfill open, it could still theoretically bring in revenue by landfilling waste from other municipalities that were not pursuing zero waste. However, such an arrangement would still present a conflict between the need for revenue and any zero-waste vision that might develop on a regional level. Given this problem of conflicting incentives, we propose that incentives could possibly be changed by charging high prices for landfilled trash while keeping recycling and composting free or relatively inexpensive, or by switching to a taxfunded municipal waste management system. Other types of incentive changes might require action beyond the municipal level; expanding the geographic and political scope will probably be necessary if zero waste is to become a sustainable vision for more than just a handful of cities. While there are barriers to achieving a “zero-waste” or other coherent waste-reduction vision within the city of Northampton, there are also barriers on a larger scale, and there are limits to how far an individual municipality can go toward zero waste. In our interviews, both David Veleta (2012) and Karen Bouquillon (2012) of the Northampton DPW expressed the importance of the “upstream” end of waste production. That is, numerous products are currently on the market that are difficult to recycle or reuse, and the social and environmental costs of disposal are not reflected in the prices consumers pay for these products, nor do producers necessarily take any responsibility for the “life cycle” of the products they sell. This lack of involvement of producers systematically undermines efforts toward waste diversion, and without addressing this problem, zero-waste initiatives are limited in the scope of what they can accomplish. Bartl (2011), writing primarily about European initiatives, advocates for turning from a “waste management” model to a “resource management” model. Focusing on only the “end of life” of a product is the traditional approach to waste management. Resource management, however, as Bartl describes it, would be an approach that would look for ways to create “cycle processes,” where production, consumption, and reuse are considered from a holistic perspective. Europe has made a number of strides toward this more holistic approach, such as through Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) directives. EPR directives were initially implemented in some individual European countries in the early nineties, and eventually adopted as policy by the European Union, though implementation varies by nation (Cahill 2010). Some countries enforce mandatory regulations that require producers to incorporate end-of-life processing into the cost of some their products and develop infrastructure to take back and reuse certain products or product wastes; in other nations EPR directives take the form of voluntary agreements. Products that have been especially focused on include vehicles and electronics, and well as packaging in general (Cahill 2010). There are no nationwide EPR initiatives in the United States, but many states have implemented similarly-minded “product stewardship” laws (EPA 2012, Product Stewardship Institute 2012). The federal EPA does have a Product Stewardship program, which operates primarily to support and facilitate efforts by smaller-level actors like state governments, businesses, and non-governmental organizations (EPA 2012). According to the Product Stewardship Institute, as of January 2012, there were 32 states that had a product stewardship law for at least one product category (Product Stewardship Institute 2012). The only category covered under Massachusetts law is mercury-added products: manufacturers are required to finance and operate collection of mercury-added automobile switches, and manufacturers of other mercury-added products are fined if they do not use some combination of collection services and public awareness outreach to achieve a minimum collection rate of these products (Product Stewardship Institute 2012). Interestingly, the current mayor of Northampton, David Narkewicz, is a member of the Massachusetts Product Stewardship Council, which is also affiliated with the Product Stewardship Institute. The fact that he is involved in upstream issues in waste management may bode well for the municipality in any future zero-waste endeavors. It seems clear that efforts in the U.S., happening mainly in a scattered fashion at state and local levels, must accumulate greater momentum if a larger scale movement toward producer responsibility is to take place. Northampton certainly is in a position to be part of that momentum. However, on another level, even the national and international EPR measures achieved in Europe have been limited in their ability to affect producer behavior or consumption on a significant scale. As Bartl (2011) points out, trends such as ever-shorter product life in personal electronics are continuing. He argues that a cultural shift is still needed--from thinking in terms of “waste” (even if we are nominally reusing that waste) to thinking in terms of sustainable resource use. Local actors may feel powerless to affect such a shift, or may believe that in the absence of strong EPR-type laws there is a limit to what can be achieved in terms of waste reduction at the local level. However, as the case of Northampton perhaps illustrates, it may in fact be pressures at the local level--political, environmental, and economic--that ultimately push communities toward zero waste. The key may be to learn to “think like an island.” In a New York Times article, Rosenthal (2010) argues that environmental regulations, careful planning practices (such as making sure that communities with waste-to-energy facilities also reap the savings in electricity costs), and government support at the national level have all been important factors in making incineration programs successful in Denmark, and the lack of similar support systems in the United States can partly explain why the U.S. “lags” in developing efficient waste-to-energy technology on a large scale. Importantly, though, Rosenthal also points out that a country like Denmark--with a much smaller land base than the United States--may have an added incentive to look for alternatives to landfilling. Geographic constraints also played a significant role in Nantucket’s move toward zero waste: the fact that Nantucket is an island meant that the costs it would face to ship its waste elsewhere would have been extremely high. Can environmental and economic constraints operate on a city like Northampton in the same way that geographic constraints operate on Denmark or Nantucket? Will the closure of the Glendale landfill be a strong enough catalyst to change the way Northampton thinks about waste? While that question is impossible to answer at this time, it is clear to us that Northampton currently faces the possibility of a serious and exciting turning point and would benefit in the long run from using this opportunity to take a leap in the direction of zero waste. REFERENCES "Alternatives to Landfill as a Waste Management Technique" (2005). Queen's University Belfast. <http://www.qub.ac.uk/ep/online/evp822/group4/alternatives.htm>. Bartl, A. (2011). “Editorial: Barriers towards achieving a zero-waste society.” Waste Management. 31: 2369-2370 Becker, A. C. (2009). "Nantucket Becomes a No-Waste Society." GreenLegals. http://greenlegals.com/2009/11/nantucket-becomes-a-no-waste-society/ Bloom, J. (2010). American wasteland: How America throws away nearly half of its food (and what we can do about it). Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. Bouquillon, Karen (2012). Personal interview. 1 May. Cahill, R., Grimes, S. M., and Wilson, D. C. (2010). “Extended producer responsibility for packaging wastes and WEEE - a comparison of implementation and the role of local authorities across Europe.” Waste Management & Research. 29(5): 455-479 Cain, C. (2009). “Landfill Questions Rejected”. The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 31 Jul.: A1. Cain, C. (2009). “Petition on landfill qualifies for city ballot”. The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 16 Sep.: B1. Cain, C. (2012). “Northampton city council eyes future loss of trash revenue”. The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 3 Feb. <http://www.gazettenet.com/2012/02/03/council-eyes-futureloss-of-trash-revenue> Center for Ecological Technology (CET) (2003). “Composting in restaurants and schools.” <http://www.northamptonma.gov/dpw/uploads/listWidget/10609/res-schools-online.pdf> City of Northampton Department of Public Works (DPW) (2009). City of Northampton Solid Waste Management Alternatives Study. Rep. 15 Jul. <http://northassoc.org/files/8945478107/landfill_alternatives_draft_report_0714.pdf>. City of Northampton Department of Public Works (DPW) (2011). "Smart Bags Start Monday August 1st!" <http://www.northamptonma.gov/dpw/Recycling/>. Concerned Citizens of Northampton (2007). “Water Supply Protection and the Landfill: An Inconvenient Truth.” <http://74.94.173.233/DPW/landfill/p5/CCON_2070410.pdf>. Contrada, Fred (2012). Personal interview. 1 Mar. "Covanta Springfield, LLC." Covanta Energy. <http://www.covantaenergy.com/facilities/facility-by-location/springfield.aspx>. Crowley, D. (2007). “Glendale Road cancer study hits roadblock.” The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 29 Aug.: A3. “Dedham firm picked to construct first phase of city’s new landfill” (1988). The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 15 Jun: 3. Di Chiro, G. (2005). “Performing a ‘Global Sense of Place’: Women’s Actions for Environmental Justice.” In Nelson, L. and Seager, J. (ed.) A Companion to Feminist Geography, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Dombkowski, Robert (2012). Personal interview.15 Mar. “Dump trucks protest” (1987). The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 19 Jan.: 14. Dwyer, D. and Holle, L. (2010). “Final report for evaluation and design for renewable energy at the Northampton landfill,” Smith College Engineering Design Clinic. http://74.94.173.233/DPW/engineering/energy/solar/NDPW_FinalReport_20110502.pdf Environmental Protection Agency (2010). Municipal Solid Waste Generation, Recycling, and Disposal in the United States: Facts and Figures for 2010. Environmental Protection Agency. Web. 8 Apr. 2012. Environmental Protection Agency (2012). “Basic Information - Product Stewardship,” Mar. <http://www.epa.gov/epawaste/partnerships/stewardship/basic.htm#state>. Faber, D.R. and Krieg, E.J. (2002). “Unequal exposure to ecological hazards: Environmental injustices in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.” Environmental Health Perspectives. 110: 277-288. Frisch, T. (2011). “Residential food waste collection rolls out.” BioCycle. Dec.: 28-30. “Garbage woes are piling up” (1987). The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 26 Jan: 15. Goodman, J. (2007). “A review of studies of landfills and human health.” Prepared by the Gradient Corporation for the City of Northampton, MA. <http://74.94.173.233/DPW/Landfill/p5/Landfill%20Studies-1.pdf>. “Green Action in Northampton Schools has Students Aim for Zero Waste” (2011). The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 10 Aug. Gorenstein, N. (1980). “City to prevent leachate from leaking from landfill.” The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 30 Sep.: 1,3. Kaufman, L. (2009). “Nudging Recycling From Less Waste to None.” The New York Times. 20 Oct.: 1-3. Layzer, J. A. (2011). “Cape wind: If not here, where? If not now, when?” In The Environmental Case: Translating Values into Policy. Washington D.C.: CQ Press. 309-347. Liss, G. (2004). "Zero Waste Standards." Durham Environment Watch. <http://www.durhamenvironmentwatch.org/Incinerator%20Files/Zero%20Waste%20Sta ndards.pdf>. Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MDEP) (2011). “Active Landfills, Sorted by Municipality & Facility Name”. May. <http://www.mass.gov/dep/recycle/actlf.pdf>. Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MDEP) Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (2010). “Draft Massachusetts 2010-2020 Solid Waste Master Plan”. Rep. 1 July. <http://www.northamptonma.gov/dpw/uploads/listWidget/10609/dswmp10.pdf>. The Massachusetts Drinking Water Regulations: Definitions, Mass. Admin. Code. 310 CMR 22.02 (2009). Newton, Robert (2012). Personal interview. 13 Apr. Odgers, Mimi (2012). Personal interview. 7 Apr. Oh, P. (1987). “Landfill expansion gets no opposition.” The Daily Hampshire Gazette. Dec 19: 4. Pollard, P. (1986). “State official says landfills can be dangerous to health.” The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 5 Dec.: 4. Pollard, P. (1988). “Landfill criteria highlight concerns.” The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 8 Jan.: 4. Product Stewardship Institute (2012). “Extended producer responsibility state laws” <http://productstewardship.us/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=280>. Rosenthal, E. (2010). “Europe finds clean energy in trash, but U.S. lags.” The New York Times. 12 Apr. "Smith at a Glance." Smith College. <http://www.smith.edu/about_justthefacts.php>. Stone, K. (1987). “Trash crisis: areas mayors legislators ask state’s help.” The Daily Hampshire Gazette. 29 Jan.: 1, 8. Tam, L. (2010). "Towards Zero Waste." San Francisco Planning and Urban Research. Feb. <www.spur.org>. Veleta, David (2012). Personal interview. 25 Apr. Wheeler, M. (1994). “Negotating NIMBYs: Learning from the Failure of the Massachusetts Siting Law.” Yale Journal on Regulation. 11: 241-286. <http://www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic/?sterms=PUBLICATION(Yale+Journ al+on+Regulation)&verb=sr&csi=7384>. Wieman, B. (2012). "Recycling Vs. Landfills or Incinerators." Green Living. National Geographic. 9 Apr. <http://greenliving.nationalgeographic.com/recycling-vs-landfillsincinerators-3266.html>.