THE CASE OF INDIA COMPETITION POLICY IN TELECOMMUNICATIONS: INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION

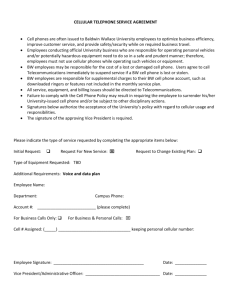

advertisement