K I : C

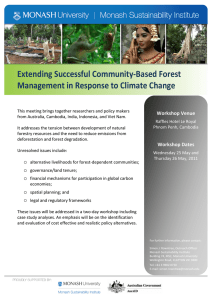

advertisement