Young bimodal bilingual narrative acquisition: Overt lexical sequence marking... video-retellings – ASL

advertisement

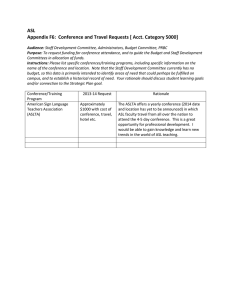

Young bimodal bilingual narrative acquisition: Overt lexical sequence marking in ASL video-retellings – ASL The literature shows that spoken (Hickmann, 1995; Peterson & McCabe, 1983) and signed (Morgan, 2006; Reilly, 2006) language narrative development is protracted, emerging around preschool age and continuing to develop until age 10. However, narrative development by bimodal bilinguals is limited to one study by Morgan (2000) tracking referential devices in two young children (ages 7;01 & 09;10) in British Sign Language (BSL) and British English. Child narratives offer a unique context for studying changes in function of specific forms throughout acquisition; where old forms take on new functions or new forms taking on old functions (Slobin, 1973). Bilingual narrative development studies of young bimodals may provide insight to the robust interaction between two langauges in two modalities. This study contributes to the burgeoning bimodal bilingual acquisition field by examining two lexical sequence markers (AND and THEN, signed equivalents of English and and then) in the signed narratives of four young bimodal bilingual children acquiring ASL and English (ages range 5;11-6:09). The acquisition of the coordinating conjunction and in spoken child narratives has been studied in Hewbrew (Berman, 1996), French (Jisa, 1985), and English (Peterson & McCabe, 1988). At about 5-7 years and sometimes beyond, and is overused, as an overt marker of sequentiality (as seen example 1). Finally, the connector becomes adult-like and is only used ocassionally to link clauses, since events in adult narratives are inherently sequential. This study shows the overuse of lexical markers to indicate sequentiality by all four bimodal bilingual children in their ASL narratives in a video-retelling task. Although the literature lexical marking (NOW & NOW-THAT) in ASL on this area is limited to a lecture setting (Roy, 2001), it seems reasonable to assume that Deaf adults frame sequential events much like hearing adults, noting that it is not modality specific. Moreover, preliminary analysis of an adult ASL narrative elicited using the same video confirms that the signer did not use the overt lexical markers that the children did. This is not surprising, as AND THEN are typically considered English borrowings. Instead, he marked sequential events through prosodic means, repetition of events through different depictive perspectives. We may expect the observed adult sequential devices to develop later, and indeed some of those aspects do appear the child renditions. Table 1 displays the most frequent lexical markers of sequentality produced by the children. Each child seems to prefer one lexical marker over another with GIA & BEN preferring THEN (see figure 1), while VAL prefers AND (see figure 2). TOM prefers his own idiosyncratic form of BUT-G followed by the indexical sign, IX(event) seen in figure 3. For an example of both AND and THEN in use to connect two sequence of events, see example 2. A casual observer might attribute the prevelance of AND THEN to English influence and the underdevelopment of ASL. However, a more sophisiticated analysis reveals a systematic use of these connectors functioning as sequence markers. This follows the same description of the changing functions of specific forms posited by Slobin. 500 Words Young bimodal bilingual narrative acquisition: Overt lexical sequence marking in ASL video-retellings – ASL Table 1: Most Frequent Lexical Markers of Sequentiality Participant Age AND THEN AND THEN Total BEN 06;09 1 10 0 11 GIA 06;04 4 12 2 19 THEN AND TOM 06;09 3 2 7 (BUT-G) BUT-G 12 IX(event) n=5; IX(event) BUT-G n=2 VAL Adult Control 05;11 8 4 1 13 0 0 0 0 (1) Ten year old boy, from Berman, 2009, p. 360: There’s a boy who has a pet frog and a pet dog, and one night after he goes to bed, the frog sneaks out. And he wakes up and its gone (2) GIA: AND THEN FS(a) BUG STILL FS(on) FS(it). AND THEN DV(path-dwn) FAST DV(fast-pathdwn) Figure 1: BEN, THEN Figure 2: GIA, AND Figure 3: TOM, BUT-G IX(event) Selected References Berman, R.A. (2009). Beyond the sentence: Language development in narrative contexts. In E. Bavin, ed. Handbook of Child Language. Cambridge University Press, 354-375. Morgan, G. (2006). The development of narrative Skills in British Sign Language In, B. Schick; M. Marschark & P. Spencer (eds). Advances in Sign Language Development in Deaf Children. Oxford University Press. Morgan, G. (2000). Discourse Cohesion in Sign and Speech. International Journal of Bilingualism, 4, 279-300. Reilly, J. (2006). Development of Nonmanual Morphology. In: Schick, B., Marschark, M, & Spencer, P.E. (eds.), Advances in Sign Language Development by Deaf Children. New York: Oxford University Press, 262-290. Roy C. Features of discourse in an American Sign Language lecture. In: C. Lucas (Ed.) The Sociolinguistics of the Deaf communitiy. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1989: 231–252. Slobin, D. (1973). Cognitive requisites for the development of grammar. In, C.A. Ferguson & D. Slobin (eds). Studies of child language development. New York: Holt Rinehart & Winston. 175-208.