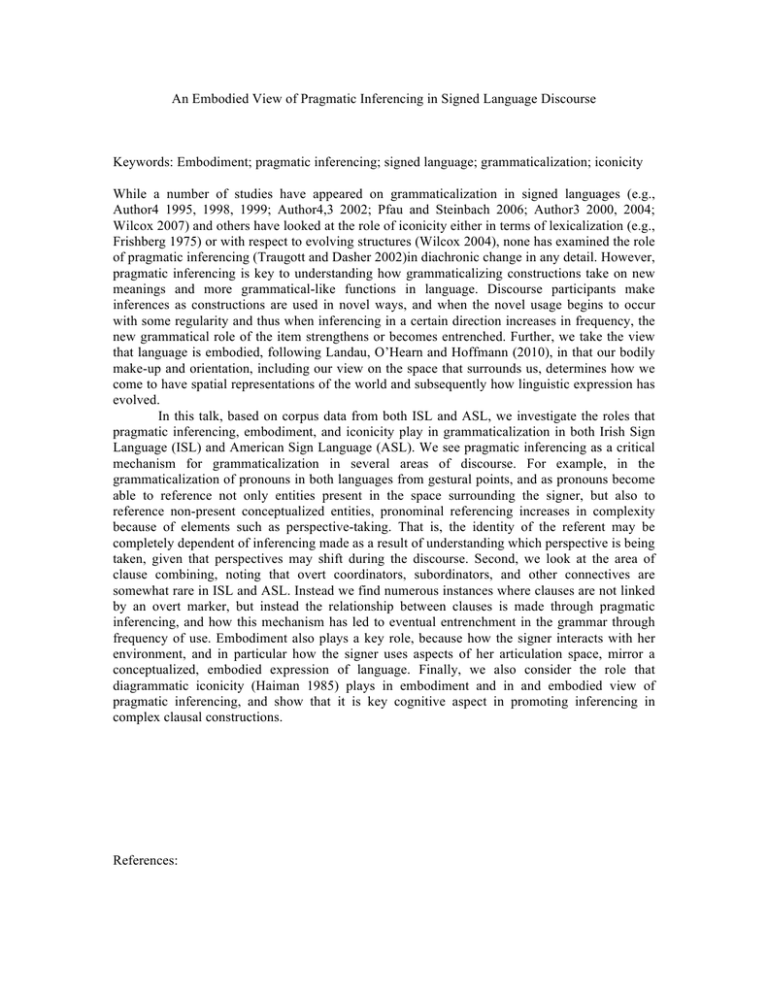

An Embodied View of Pragmatic Inferencing in Signed Language Discourse

advertisement

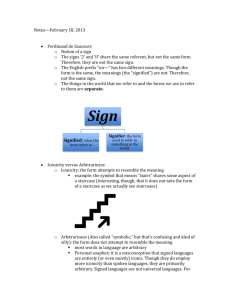

An Embodied View of Pragmatic Inferencing in Signed Language Discourse Keywords: Embodiment; pragmatic inferencing; signed language; grammaticalization; iconicity While a number of studies have appeared on grammaticalization in signed languages (e.g., Author4 1995, 1998, 1999; Author4,3 2002; Pfau and Steinbach 2006; Author3 2000, 2004; Wilcox 2007) and others have looked at the role of iconicity either in terms of lexicalization (e.g., Frishberg 1975) or with respect to evolving structures (Wilcox 2004), none has examined the role of pragmatic inferencing (Traugott and Dasher 2002)in diachronic change in any detail. However, pragmatic inferencing is key to understanding how grammaticalizing constructions take on new meanings and more grammatical-like functions in language. Discourse participants make inferences as constructions are used in novel ways, and when the novel usage begins to occur with some regularity and thus when inferencing in a certain direction increases in frequency, the new grammatical role of the item strengthens or becomes entrenched. Further, we take the view that language is embodied, following Landau, O’Hearn and Hoffmann (2010), in that our bodily make-up and orientation, including our view on the space that surrounds us, determines how we come to have spatial representations of the world and subsequently how linguistic expression has evolved. In this talk, based on corpus data from both ISL and ASL, we investigate the roles that pragmatic inferencing, embodiment, and iconicity play in grammaticalization in both Irish Sign Language (ISL) and American Sign Language (ASL). We see pragmatic inferencing as a critical mechanism for grammaticalization in several areas of discourse. For example, in the grammaticalization of pronouns in both languages from gestural points, and as pronouns become able to reference not only entities present in the space surrounding the signer, but also to reference non-present conceptualized entities, pronominal referencing increases in complexity because of elements such as perspective-taking. That is, the identity of the referent may be completely dependent of inferencing made as a result of understanding which perspective is being taken, given that perspectives may shift during the discourse. Second, we look at the area of clause combining, noting that overt coordinators, subordinators, and other connectives are somewhat rare in ISL and ASL. Instead we find numerous instances where clauses are not linked by an overt marker, but instead the relationship between clauses is made through pragmatic inferencing, and how this mechanism has led to eventual entrenchment in the grammar through frequency of use. Embodiment also plays a key role, because how the signer interacts with her environment, and in particular how the signer uses aspects of her articulation space, mirror a conceptualized, embodied expression of language. Finally, we also consider the role that diagrammatic iconicity (Haiman 1985) plays in embodiment and in and embodied view of pragmatic inferencing, and show that it is key cognitive aspect in promoting inferencing in complex clausal constructions. References: Frishberg, Nancy. 1975. Arbitrariness and iconicity: Historical change in American Sign Language. Language 51, 696-719. Haiman, John. 1985. Symmetry. In John Haimain Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. 73-95. (Ed.), Iconicity in Syntax. Landau, Barbara, Kirsten O’Hearn, and James E. Hoffman. 2010. Tethering to the world, Coming undone. In Kelly S. Mix, Linda B. Smith, and Michael Gasser (Eds.), The Spatial Foundations of Language and Cognition. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. 132-156. Author4. 1995. The Polygrammaticalization of FINISH in ASL. MA thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. Author4. 1998. Topicality in ASL: Information Ordering, Constituent Structure, and the Function of Topic Marking. Doctoral dissertation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Author4. 1999. The grammaticization of topics in American Sign Language. Studies in Language, 23:2, 271-306. Author4,3. 2002. Gesture as the substrate in the process of ASL grammaticization. In Richard Meier, Kearsy Cormier, and David Quinto-Pozos (Eds.), Modality and Structure in Signed and Spoken Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 199-223. Pfau, Roland, and Markus Steinbach. 2006. Modality-Independent and Modality-Specific Aspects of Grammaticalization in Sign Languages. Linguistics in Potsdam 24, Potsdam: Univ.Verl. Author3. 2000. A Syntactic, Pragmatic Analysis of the Expression of Necessity and Possibility in American Sign Language. Doctoral dissertation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM. Author3. 2004. Information ordering and speaker subjectivity: Modality in ASL. Cognitive Linguistics 15(2), 175-195. Traugott, Elizabeth Closs, and Richard B. Dasher. 2002. Regularity in Semantic Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wilcox, Sherman. 2004. Cognitive iconicity: Conceptual spaces, meaning, and gesture in signed language. Cognitive Linguistics 15(2), 119-147. Wilcox, Sherman. 2007. Routes from gesture to language. In Elena Pizzuto, Paola Pietrandrea, and Raffaele Simone (Eds.), Verbal and Signed Languages: Comparing Structures, Constructs and Methodologies. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter. 107-131.