Achieving fairness in trading between supermarkets and their agrifood supply chains

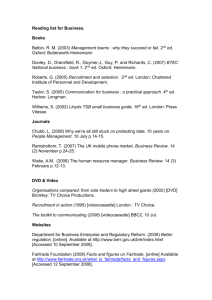

advertisement