Gastroduodenal Disorders Peptic Ulcer Disease Definition:

advertisement

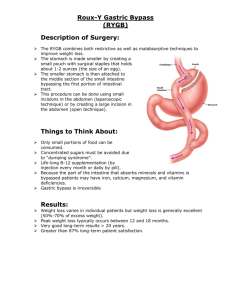

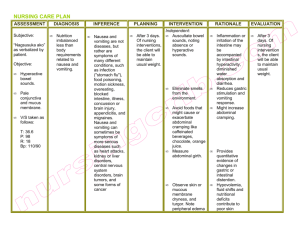

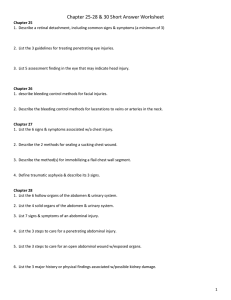

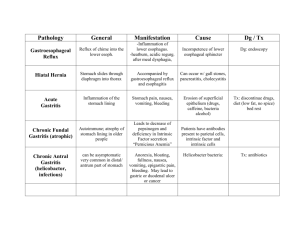

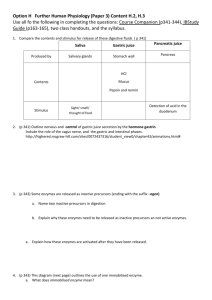

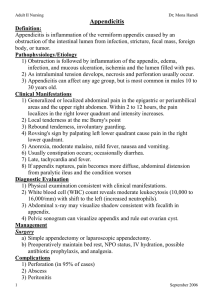

Gastroduodenal Disorders Peptic Ulcer Disease Definition: A peptic ulcer is a lesion in the mucosa of the lower esophagus, stomach, pylorus or duodenum (Fig. 1). The stomach is divided on the basis of the physiologic function into two main portions. 1) The proximal two third, the fundic gland area, acts as a receptacle for ingested food and secrete acid and pepsine. 2) The distal third, the pyloric gland area, mixes and propels food into the duodenum and produces the hormone gastrein. "Peptic" lesions may occur in the esophagus (esophagitis), m stomach, (gastritis), or duodenum (duodenities). Note peptic ulcer sites and common inflammatory sites in the previous Fig. Pathophysiology/Etiology 1) Helicobacter pylori infection—exact mechanism is unclear. 2) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced ulcers. a. The risk of gastric ulcers is much greater than duodenal ulcers. b. Aspirin is the most ulcerogenic NSAID. 3) Hypersecretion of acid: a. Believed to be caused by an overactive vagus nerve, which stimulates the release of gastrin. b. Methylxanthines (tea, coffee, cola, and chocolate) and smoking may also increase gastric acidity c. Found in disorders such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome tumors of the pancreas which increases secretion of gastrin(multiple peptic ulcers). 4) Genetic predisposition and stress appear to be controversial factors. Clinical Manifestations Gastric ulcers Lesion. Location of lesion. Clinical Manifestations Duodenal ulcers Superficial; smooth margins; round, oval or cone shaped. Antrum. Also in body and fundus of the stomach. Penetrating Pain occurring in the high left epigastric area radiating to the back & upper abdomen Described as dull, aching, and gnawing Pain located to the right of the midline epigastric region radiating to the back Describes as burning , cramping, pressure like pain across midepigastrium & upper abdomen Pain is worse with food Pain may increase when the stomach is empty, approximately 1½ to 3 hours after eating. Patients may report relief from pain after eating or taking antacids Pain may awaken person at night, periodic and episodic Not relieved with antacids as well as with duodenal Some clients have constant pain or no clear pattern of discomfort Weight loss Black or tarry stools from bleeding First 1-2 cm of duodenum. Weight gain if food relieves the pain Diagnostic Evaluation 1) Upper GI series usually outlines ulcer or area of inflammation 2) Fiberoptic panendoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy)—visualization of duodenal mucosa; identifies inflammatory changes, ulcers, lesions, bleeding sites, and malignancy. 3) Cytologic brushings and biopsies may be performed to obtained samples. 4) Serial stool specimens to detect occult blood 5) Gastric secretory studies (gastric acid secretion test and the serum gastric level test)—elevated in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome 6) Serum test for H. pylori antibodies may be positive. Management A. Specific Pharmacotherapy 1) H2 receptor antagonists, such as cimetidine (Tagamet), ranitidine (Zantac), famotidine (Pepcid)—inhibit action of histamine on the H2 receptors of the parietal cells, thus reducing gastric acid output and concentration. 2) Antisecretory or proton pump inhibitor drug omeprazole (Prilosec)— inhibits the production of hydrochloric acid in the stomach. Heals ulcers quickly (in 4 to 8 weeks). 3) Cytoprotective drug sucralfate (Carafate)—adheres to and protects the ulcer surface by forming a protective barrier against acid, bile, pepsin. 4) Acid-neutralizing agents (antacids)—provide additional relief of symptoms. Not used alone as treatment. 5) Antisecretory and cytoprotective drug misoprostol (Cytotec)— prostoglandin analogue inhibits hydrochloric acid production in the stomach. 6) Antidiarrheal agent bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol)—has antibacterial action against H. pylori and enhances mucosal protection through bicarbonate and prostaglandin production. 7) Antibiotics such as tetracycline and metronidazole (Flagyl) used with bismuth as “triple therapy” to eradicate H. pylori. 8) For NSAID ulcers—discontinue NSAID and treat as mentioned above. If NSAID is restarted, administer with misoprostol. B. Dietary Measures 1) Well-balanced diet, high fiber content, meals at regular intervals ( 6 meals a day). 2) Avoid caffeine, colas, and alcohol. 3) Avoid smoking—decreases healing rate and increases recurrence. C. Surgery Indicated in emergency situations for uncontrolled bleeding or bleeding that developed despite chronic drug maintenance therapy. 1) Vagotomy: (cutting of vagus nerve) To eliminate the stimulus that triggers gastric acid secretion by the gastric cells; can choose to cut all or portions 2) Subtotal gastrectomy a. The resected portion includes a small cuff of the duodenum, pylorus, and from two thirds to three quarters of the stomach. b. The duodenum or side of the jejunum is anastomosed to the remaining portion of the stomach. 3) Total gastrectomy esophagus is anastomosed to jejunum Complications 1) GI hemorrhage 2) Ulcer perforation 3) Gastric outlet obstruction Post Operative Complications: 1) Dumping Syndrome. 2) Postprandial hypoglycemia. 1-Dumping syndrome: The term used for a group of unpleasant vasomotor and gastro intestinal symptoms includes reducing the reservoir capacity of the stomach, associated with meal having a hyperosmolar composition. Occur after gastric surgery in approximately one third to one half of patients. The stomach no longer has control over the amount of gastric chyme entering the small intestine. Consequently a) A large bolus of a hypertonic fluid enters the intestine and result in fluid being drawn into the bowel lumen. This creates a decrease in plasma volume. b) Distension of the bowel lumen (as a result of this bowel shift) which stimulate intestinal motility and the urge to defecate. The onset of symptoms occurs at the end of the meal or within 15-30 min after eating, lasts for no longer than an hour after meals. The patient usually describes a) Feeling of generalized weakness, sweating, palpations, tachycardia, and dizziness. (Theses symptoms attributed to the sudden decreases in plasma volume). b) Abdominal cramp, borborygmi, and the urge to defecate. 2-Postprandial Hypoglycemia. As a bolus of fluid high in carbohydrate get into the small intestine results in hyperglycemia and the release of excessive amounts of insulin into the circulation. A secondary hypoglycemia then occurs 2 hours after meals. The immediate ingestion of sugared fluid or candy relieves the hypoglycemic symptoms. To avoid similar occurrence: the patient should be instructed to limit the amount of sugar consumed with each meal , and to eat small frequent meals with moderate amount of proteins and fat. Nursing Assessment 1) Determine location, character, radiation of pain, factors aggravating or relieving pain, how long it lasts, when it occurs. 2) Ask about eating patterns, regularity, types of food, eating circumstances. 3) Take a social history of alcohol consumption and smoking. 4) Ask about medications (especially aspirin, anti-inflammatory drugs, or steroids). 5) Determine if GI bleeding has been experienced. 6) Take vital signs, including lying, standing, and sitting blood pressures and pulses, to determine if orthostasis is present due to bleeding. Nursing Diagnoses A. Fluid Volume Deficit related to hemorrhage B. Pain related to epigastric distress secondary to hypersecretion of acid, mucosal erosion, or perforation C. Diarrhea related to GI bleeding or antacid therapy D. Altered Nutrition, Less Than Body Requirements, related to the disease process E. Knowledge Deficit related to physical, dietary, and pharmacologic treatment of disease. Nursing Interventions A. Avoiding Fluid Volume Deficit 1) Monitor intake and output continuously to determine fluid volume status. 2) Observe stools for occult blood. 3) Monitor hemoglobin and hematocrit and electrolytes. 4) Administer prescribed IV fluids and blood replacement, as prescribed. 5) Insert an NG tube as prescribed and monitor the tube drainage for signs of visible and occult blood. 6) Administer medications through the NG tube to neutralize acidity, as prescribed. 7) Prepare patient for saline lavage, as ordered. 8) Observe the patient for an increase in pulse and a decrease in blood pressure (signs of shock). B. Achieving Pain Relief 1) Encourage bed rest to reduce physical activity and to separate patient from usual environment if pain continues. 2) Provide small, frequent meals to prevent gastric distention if not NPO. 3) Teach the patient that caffeine, alcoholic beverages, and nicotine may increase gastric acidity and promote erosion of the gastric mucosa. 4) Advise the patient about the irritating effects on the gastric mucosa of certain drugs, such as aspirin, NSAIDs, and certain antibiotics. 5) Administer prescribed medication C. Decreasing Diarrhea 1) Monitor patient’s elimination patterns to determine effects of medications. 2) Monitor vital signs and watch for signs of hypovolemia. Persistent diarrhea may be a sign of bleeding. 3) Restrict foods and fluids that promote diarrhea: raw vegetables, fruits, whole grain cereals, carbonated drinks. 4) Administer antidiarrheal medication as prescribed. 5) Watch for signs of impaired skin integrity (erythema, soreness) around anus to promote comfort and decrease risk of infection. D. Achieving Adequate Nutrition 1) Eliminate foods that cause pain or distress; otherwise, the diet is usually not restricted. 2) Provide small, frequent feedings on time. This will decrease distention and the release of gastrin. Frequent feedings also help neutralize gastric secretions and dilute stomach contents. However, eating small, frequent meals or snacks can lead to acid rebound, which occurs 2 to 4 hours after eating. 3) Advise the patient to avoid coffee and other caffeinated beverages as well as carbonated drinks; these may increase acid. 4) Advise the patient to avoid extremely hot or cold food or fluids, to chew thoroughly, and to eat in a leisurely fashion for better digestion. 5) Administer parenteral nutrition if bleeding is prolonged and patient is emaciated, as ordered. E. Educating About the Treatment Regimen 1) Explain all tests and procedures to increase knowledge and cooperation; minimize anxiety. 2) Review the health care provider’s recommendations for diet, activity, medication, and treatment. Allow time for questions, and clarify any misunderstandings. 3) Give the patient a chart listing medications, dosages, times of administration, and desired effects to promote compliance. 4) Instruct the patient to notify health care provider immediately if there is any evidence of bleeding, tarry stools, or dizziness; may indicate an acute bleeding episode. Patient Education/ Health Maintenance Teach the patient the following: 1) Modify lifestyle to include health practices that will prevent recurrences of ulcer pain and bleeding. 2) Plan for rest periods and avoid or learn to cope with stressful situations; avoid fatigue. 3) Avoid specific foods known to cause the individual patient distress and pain. 4) Recognize signs of potential problems (midepigastric pain). Reinstitute anti-ulcer medication if necessary. 5) Take antacids 1 hour after meals, at bedtime, and when needed. Warn the patient that antacids may cause changes in bowel habits. 6) Do not take H2 receptor antagonists at the same time as sucralfate. This reduces the therapeutic effects of the drugs. Evaluation A. Vital signs stable; intake and output equal B. Demonstrates improved comfort C. Decreased frequency of stools D. Eating several meals a day; reports no loss of weight E. Can describe peptic ulcer disease, its treatment, and complications; complies with treatment regimen Appendicitis Definition: Appendicitis is inflammation of the vermiform appendix caused by an obstruction of the intestinal lumen from infection, stricture, fecal mass, foreign body, or tumor. Pathophysiology/Etiology 1) Obstruction is followed by inflammation of the appendix, edema, infection, and mucous ulceration, ischemia and the lumen filled with pus. 2) As intraluminal tension develops, necrosis and perforation usually occur. 3) Appendicitis can affect any age group, but is most common in males 10 to 30 years old. Clinical Manifestations 1) Generalized or localized abdominal pain in the epigastric or periumbilical areas and the upper right abdomen. Within 2 to 12 hours, the pain localizes in the right lower quadrant and intensity increases. 2) Local tenderness at the mc Burny's point 3) Rebound tenderness, involuntary guarding. 4) Rovsing's sign by palpating left lower quadrant cause pain in the right lower quadrant. 5) Anorexia, moderate malaise, mild fever, nausea and vomiting. 6) Usually constipation occurs; occasionally diarrhea. 7) Late, tachycardia and fever. 8) If appendix ruptures, pain becomes more diffuse, abdominal distension from paralytic ileus and the condition worsen Diagnostic Evaluation 1) Physical examination consistent with clinical manifestations. 2) White blood cell (WBC) count reveals moderate leukocytosis (10,000 to 16,000/mm) with shift to the left (increased neutrophils). 3) Abdominal x-ray may visualize shadow consistent with fecalith in appendix. 4) Pelvic sonogram can visualize appendix and rule out ovarian cyst. Management Surgery a) Simple appendectomy or laparoscopic appendectomy. b) Preoperatively maintain bed rest, NPO status, IV hydration, possible antibiotic prophylaxis, and analgesia. Complications 1) Perforation (in 95% of cases) 2) Abscess 3) Peritonitis Nursing Assessment 1) Obtain history for location and extent of pain. 2) Auscultate for presence of bowel sounds; peristalsis may be absent or diminished. 3) On palpation of the abdomen, assess for tenderness anywhere in the right lower quadrant, but often localized over McBurney’s point (point just below midpoint of line between umbilicus and iliac crest on the right side). 4) Assess for rebound tenderness in the right lower quadrant as well as referred rebound when palpating the left lower quadrant. 5) Assess for positive psoas sign by having the patient attempt to raise the right thigh against the pressure of your hand placed over the right knee. Inflammation of the psoas muscle in acute appendicitis will increase abdominal pain with this maneuver. 6) Assess for positive obturator sign by flexing the patient’s right hip and knee and rotating the leg internally. Hypogastric pain with this maneuver indicates inflammation of the obturator muscle. Nursing Diagnoses 1) Pain related to inflamed appendix 2) Risk for Infection related to perforation Nursing Interventions A. Relieving Pain 1) Monitor pain level, including location, intensity, pattern. 2) Assist patient to more comfortable positions, such as semi-Fowler’s and knees up. 3) Restrict activity that may aggravate pain, such as coughing and ambulation. 4) Apply ice bag to abdomen for comfort. 5) Give analgesics only as ordered after diagnosis is determined. 6) Avoid indiscriminant palpation of the abdomen to avoid increasing the patient’s discomfort. 7) Do not give antipyretics to mask fever and do not administer cathartics, because they may cause rupture. B. Preventing Infection 1) Monitor frequently for signs and symptoms of worsening condition indicating perforation, abscess, or peritonitis: increasing severity of pain, tenderness, rigidity, distention, ileus, fever, malaise, tachycardia. 2) Administer antibiotics as ordered. 3) Promptly prepare patient for surgery. Evaluation 1) Verbalizes increased comfort with positioning and analgesics 2) Afebrile; no rigidity or distention Peritonitis Definition Peritonitis is a generalized or localized inflammation of the peritoneum, the membrane lining the abdominal cavity and covering visceral organs. Usually it is result from bacterial infection. Pathophysiology/Etiology A. Primary Peritonitis Acute, diffuse, relatively rare 1) Occurs primarily in young females; often due to pathogenic bacteria (streptococci, pneumococci, gonococci) introduced through uterine tubes or through hematogenous spread. 2) In patients with nephrosis or cirrhosis, the offending organism is most often Eschericia coli. B. Secondary Peritonitis Contamination by GI secretions. 1) Complication of appendicitis, diverticulitis, peptic ulceration, biliary tract disease, colon inflammation, volvulus, strangulated obstruction, abdominal neoplasm. 2) May occur after abdominal trauma: gunshot wound, stab wound, blunt trauma from motor vehicle accident. 3) Postoperative complication a) May occur after intraoperative intestinal spillage. b) Compromised patients are vulnerable (those with diabetes, malignancy, malnutrition, or receiving steroid therapy). Clinical Manifestations 1) Initially, local type of abdominal pain tends to become constant, diffuse, and more intense. 2) Abdomen becomes extremely tender and muscles become rigid: rebound tenderness and ileus may be present; patient lies very still, usually with legs drawn up. 3) Percussion—resonance and tympany due to paralytic ileus; loss of liver dullness may indicate free air in abdomen. 4) Auscultation—decreased bowel sounds. 5) Nausea and vomiting often occur; peristalsis diminishes; anorexia is present. 6) Elevation of temperature and pulse as well as leukocytosis. 7) Fever; thirst; oliguria; dry, swollen tongue; signs of dehydration. 8) Weakness, pallor, diaphoresis, and cold skin are a result of the loss of fluid, electrolytes, and protein into the abdomen. 9) Hypotension and hypokalemia may occur. 10) Shallow respirations may result from abdominal distention and upward displacement of the diaphragm. Note: With generalized peritonitis, large volumes of fluid may be lost into abdominal cavity (can account for losses to 5 L/day). Diagnostic Evaluation 1) WBC to show leukocytosis (leukopenia if severe). 2) Arterial blood gases—may show metabolic acidosis with respiratory compensation. 3) Urinalysis—may indicate urinary tract problems as primary source. 4) Peritoneal aspiration (paracentesis)—to demonstrate blood, pus, bile, bacteria (gram staining), amylase. 5) Abdominal x-rays—may show gas and fluid collection in small and large intestines, generalized dilatation. 6) CT of abdomen—may reveal abscess formation. 7) Laparotomy—to identify the underlying cause. Management 1) Treatment of inflammatory conditions preoperatively and postoperatively with antibiotic therapy—may prevent peritonitis. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy to cover aerobic and anaerobic organisms is initial treatment, followed by specific antibiotic therapy after culture and sensitivity results. 2) Bed rest, NPO status. 3) Parenteral replacement of fluid and electrolytes. 4) Analgesics for pain; antiemetics for nausea and vomiting. 5) Nasogastric intubation to decompress the bowel. 6) Possibly rectal tube to facilitate passage of gas. 7) Operative procedures to close perforations, remove infection source (i.e., inflamed organ, neurotic tissue), drain abscesses, and lavage peritoneal cavity. 8) Abdominal paracentesis may be done to remove accumulating fluid. Complications 1) Intraabdominal abscess formation (ie, pelvic subphrenic space) 2) Septicemia Nursing Assessment 1) Assess for abdominal distention and tenderness, guarding, rebound, hypoactive or absent bowel sounds to determine bowel function. 2) Observe for signs of shock—tachycardia and hypotension. 3) Monitor vital signs, arterial blood gases, complete blood count, electrolytes, and central venous pressure to monitor hemodynamic status and assess for complications. Nursing Diagnoses A. Pain related to peritoneal inflammation B. Fluid Volume Deficit related to vomiting and interstitial fluid shift C. Altered Nutrition, Less Than Body Requirements, related to GI symptomatology Nursing Interventions A. Achieving Pain Relief 1) Place the patient in semi-Fowler’s position before surgery to enable less painful breathing. 2) After surgery, place the patient in Fowler’s position to promote drainage by gravity. 3) Provide analgesics as prescribed. B. Maintaining Fluid/Electrolyte Volume 1) Keep patient NPO to reduce peristalsis. 2) Provide IV fluids to establish adequate fluid intake and to promote adequate urinary output, as prescribed. 3) Record accurately intake and output, including the measurement of vomitus and NG drainage. 4) Minimize nausea, vomiting, and distention by use of NG suction, antiemetics. 5) Monitor for signs of hypovolemia: dry mucous membranes, oliguria, postural hypotension, tachycardia, diminished skin turgor. C. Achieving Adequate Nutrition 1) Administer TPN, as ordered, to maintain positive nitrogen balance until patient can resume oral diet. 2) Reduce parenteral fluids and give oral food and fluids per order, when the following occur: a) Temperature and pulse return to normal. b) Abdomen becomes soft. c) Peristaltic sounds return (determined by abdominal auscultation). d) Flatus is passed and patient has bowel movements. Patient Education/ Health Maintenance 1) Teach patient and family how to care for open wounds and drain sites, if appropriate. 2) Assess the need for home care nursing to assist with wound care and assess healing; refer as necessary. Evaluation A. Minimal analgesics needed; abdomen soft, nontender, and no distention B. Balanced intake and output, no evidence of dehydration or electrolyte imbalances C. Bowel sounds present; tolerating soft diet.