WATER POLLUTION, THE FEDERAL WATER ... ACT, AND THE RIVERS AND ...

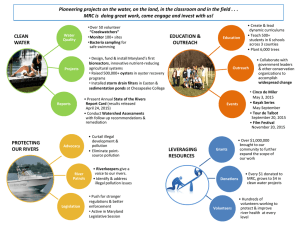

advertisement

WATER POLLUTION, THE FEDERAL WATER POLLUTION CONTROL

ACT, AND THE RIVERS AND HARBORS ACT OF 1899: EXERCISES IN FUTILITY

BRUCE ROBERSON

WATER POLLUTION, THE FEDERAL WATER POLLUTION ' CONTROL

ACT, AND THE R~VERS AND' HARBORS ACT OF 1899:

EXERCISES IN FUTALITY

AN OVERVIEW OF THE PROBLEM

~f t~e ' industrial

In analyzing the role

polluter of the

public waterways, one must realize what has for too long been

ignored by government, tndustry and the public at large, that

there is a limited amount of water., ' For too long 'America'S

,

water supply has been, the victim ' of over optimism.

To most

people, the water'supply

has consisted' of a never. ending com.,

,

modity, to ,be used

~

'

~ndiscriminately , for

drinking, for farm-

ing and for manufacturing, and i't has not been until the last

10 or 20 years, when the effects of ': pollution became apparent on the face of America's cherished and yet to of_ten

neglected waterways, that most Americans realized that there

were limits on the burden that could be borne by America's

water supply.

This attitude 'of

neglec~

is

ch~racterized

clearly by authors su~h as John V. Kritilla, uAmerican culture and character have been influenced profoundly by the

open rural country side and the wilderness beyond.

further we remove from the conditions of a more

The

prim~tive

America, the greater is our nostalgia for the conditions of

,

earlier times.

,

But despite the many influential and eloquent

1

2

advocates for preserving the American scene, the assaults upon the American landscape and the erosion of its

~natur~l

en-

vironment continue ... l

\ The urgency of the situation is best dramatized in Sigurd Grava's, The

~

Planning Aspects of Water Pollution

~

\

Control, where he states, ... (T) he time has come to apply this

knowledge of pollution control not as the basis for stop gap'

and emergency measures in crisis situations but in a systematic and preventive way for all urban settlements, regions

the President

of the

and the environment as a whole." 2 , Even

I

•

United States', when out).ining t~e legislative proposals and

administrative

ac~ions

to improve envi.ronmental quality,

~

noted the methodical past and ·the necessity for immediate

corrective action.

"(L)ike

tilled a plot of land to

tho~e

in the last century who

e~haustion

and the moved on to an-

other, we in this country have too casually and too long

abused our

enviro~~ent •

. ,The

ti~e

no longer to repair the damage

has come when we can wait

~lready

done, and to estab-

lish new criteria to guide us in· the future ... 3

advise of the

preside ~t,

it 'is not

~he

Heading the

objective of this

writer or this paper to search for villians among the rank

and file of industry, but to recognize that-industry, like

other parts of the American

pollution of ,the

so~iety,

public , water~ays,

have contributed to the

and once having estab-

lished that industry is responsible ·to some degree, to analyze

3

the possible effectiveness of two systems of enforcing acceptable standard short of zero pollution.

THE EXTENT OF THE WATER POLLUTION PROBLEM AND

THE NECESSITY. FOR ACTION

\

~

According to Harvey Lieber, director of ·the Washington

Semester Program, of the American "University, "The leading

I

source of man-made water po.i1ut~mts in the Unite,d States is

manufacturing, fo11o~ed by domestic or municipal wastes.,,4

The January 26, 1970 . issue of News.week: report,s that, "[N] ationa11y, Federal government experts' estimate the food, textile, paper and c1;lemica1, coal,

iro~, .

,rubber, metals, machin-

.\

ery and transportation iridustries ' spill a staggeri'ng 25 tri1lion gallons of waste water

c:

ann~a11y."J

In 1963 manufacturing

generated about three time's the amount of waste produced by

the 120 million people who were served by sewers in the United

States.

Today it ,~s est;i.mated ~hat this estimate would ap-

proach four to on~.6

Another consideration

when'd~a1ing

with the.prob1em of

water pollution at the indu$tria1 level is t~at industrial

"

pollution is more likely to

ammonia

arsenic

barium

boron

cho1oride

chromium

copper

iron

.

c~ntain

complex compounds such as:

lead

manganese

phosporous

su1phates

zinc

phenols

cyanide

4

It has also been noted that pollution control is complicated

by the 400 to 500 new chemical substances createG each year.'

It should be remembered that in . addition to these comparatively new wastes, that in 'many cases defy present methods of

treatment and or

o

removal,~

that increasing production of goods

increases the amount of common industrial waste products that

are dumped into the waterways. 'Estimates of the

,

services dramatically

protr~ys,

'in billions of

~ublic

g~llons

health

per day,

'j

the increasing demand · for water

.

and

e~perienced

by all sectors of

,

the American society,

Municipal

Industrial ,

especially industry:

1900

1920

1940

1950

1960

1970

1980

3.0'

6.0

10.1

14.1

22.0

27.0

37.2

15.0

27.2

52·.0

14.0

159.9

218.3

394.2

74.l"

104.6

141.0

165.9

165.7

..

Agricultural

22.2

58.4

The net effect of this increasing demand among all sectors of the societ}!"

for

. Americ~s

limited water resourc-e, is

that there has been a dramatic increase in the· amount of

pollutants "dumped" into a

demin~s~ing

supply of

~'usable"

water.

POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS TO THE PROBLEM:

THE PRIVATE SECTOR

Having established that some action is necessary to pro··

tect the water supply, the next question then is what agency

5

is the proper channel to deal with the problem.

be considered is the private sector (i.e. the

The first to

in~tatio~

of

action by the individual citizens or private interest groups).

It is apparent from even a cursory reading of material available on the subject that the private sector lacks both the

willingness ,and the financial abil{ty to cop~ with the problem.

"Although some industriaYwastes are very difficult to

I

advance~

remove from water and technOlogy has not

sufficiently

~

to handle such a· problem, most

to control. iO

in~ustrial

The problem is cost. ll

wastes are subject

Next is the proposi-

tion that industry itself can effectively deal with the problem.

Again the

f~nancial considera~io~

comes into

play~

but

this time its effect is substantially 'different •. ~ndustry,

I

,

like practically all other , segments of the American economy

is based on the cornerstone of competitive 'advantage, and it

would be foolish to conceive of any industrialist, no matter

how well intentioned, who would _sacrifice a competitive-ad!

-

vantage no matter how small, and thereby jeopardize the very

existence of his 'company, for the goal of pollution control

or elimination.

Secondly, there is the very real probability

.

"'

.

that many industrialists don't, feel that it is , their obligation to deal with the problem. l2

ized by statements like:

'This attitude is character-

"Some degree of pollution is part

of the cost involved in achieving benefits made possible by

a

technologiC~l society.~~3

"Industry can spend nothing on

6

water pollution control it does not first earn in profit.

nl4

npublic enthusiasm for pollution control 'is matched by ,reluctance to pay even a modest share of the cost.n lS

Therefore

it would seem unrealisti9 to assume that industry will, without a significant change in the attitude of either, the public,

\

or an improbable reversal in the American economic structure,

make more than a publicity orientated effort to ~eal with

the problem of industrial P9llution of the public waterways.

The final possible solution to the water pollution problem is

the government, and

~merica

has seen a , defini~e response from

the governmental sector, with

v~rying

levels of achievement.

I

POSSIBLE &OLUTIONS TO

T~E ' PROBLEM:

TH~

GOVERNMENT AND CONFLICTING INTERESTS

It is because of these varying degrees of success that

it became important that this paper deal with the pollution

problem.

Not only/is it

,necess~ry 'th~t

something be done

about the problem of pollution, ,but it is additionally necessary that the problem be deal~ wltbon a ~niversally equal

plane.

To do otherwise woul'd , be to '_place an impossible bur-

"

den on certain industries which, although they do contribute

to the problem, contribute no more and no less than any other

industry.

In addition to the necessity of evenhandedness, that

must be an overriding consideration,' is the additional con-

?

sideration that was observed by Roscoe Pound when he stated,

"the end of law is the adjustment or harmonizing of con.flicting or overlapping desires and

~laims,

so as to give effect

to as, much as possible -'with the least sacrifice. ,,16

What then are the conflicting and overlapping.desires and

claims that'JDust be harmonized by any solution to the ' pollution problem?

First there is the desire of the various inI

The tradi~.ional ap-

dustries involved to maximize profit.

-~

proach to the goal of , maximum

pro~it

has been to lower the

costs of production by disposing industrial wastes in the most

inexpensive manner possible, which in many cases necessitates

disposal in public waterways.l?

I

As was noted by Arnold W.

'

,

Rei tze, Jr., in "Was'tes, Water., and Wishful Thinking: . The

,

Battle of Lake Erie," in Vol. 20, Case Western Reserve L.R.,

"(I)n the extreme case, .a businessman faced · with removing a

building might burn it down rather than remove it piece by

piece even though tfe burni~g p ~ocess would destroy a town.

This is not very different from

~hat

is presently being done

to our environment by industrial·.w~ter pollution. ,!18

And as

is noted later in the article: by Mr. Reitze, "the capitol

,

-

'

requirements of dealing with the ·pollution problem are astronomical, and any attempt to regulate pollution would likely

bring a cry of anguish followed , by "scientific" proof that

it would drive the company out of business and cost-many

workers their jobs.,,19

8

On the other side of the coin of conflicting interests

that will need to be balanced by any action that 'is in~tiated

to deal with the problem of water pollution,' is the necessary

quali.ty of life that is to be: maintained by citizens of the

united States and the world.

Conservationists are quick to;point out that unless some

action is' taken within the immedi~te ' future, no amount of

I

action will suffice to meet.; the ' needs of future generations.

"

As was pointed out by Rene' Dubos,in the Environmental Handbook, "Man has a remarkable ability to:

develo~

some form of

tolerance to conditions~extreme~y different from those under

which he evolved.

. This ' has , led

to the . belief that through

~

\

social and technological 'innovations, 'he can endlessly modify

his ways of life without risk.

But the facts do not justify

-

this euphoric attitude. : Modern man can adapt biologically to

the technological environment · only in so far as the mechanisms

of adaptation are }fotentially

For this reason, we can almost

cannot achieve successful

p ~ esent

~ake

biologic~l

in his generic code.

it for granted that he

adaptation to insults

with which he has had ,no experience. with in

h~s

biological

past, such as the shrill noises of modern equipment, the exhausts of automobiles and factories, the countless new synthetic products that'get into t?e air, water and food.

The

limits that m~st be imp~sed o~ social and technological innovations are determined 'not by scientific knowledge or

9

practical know how, but by the biological and mental nature of

man which is essentially unchangeable. ,,20

This seems t;.o re-

present the attitude of many of . the ecologists, in that they

are Of the opinion that

~he

ecosystem of the United States

has reached the point of diminishing returns and that unless

effective aQtion is taken man will 'no longer 'b e able to adapt

to the environment which he has" p~oducted for himself.

r

In addition to this co~sideration it seems ~at many

believe that efforts to produce the technology to deal with

the problem will only result in further additions to the

problem and thereby compound the situation.

Jon Breslaw in

th~

As was noted by

Environmental HaItdbpok, "Market economies

~

are effective instruments' for ·organizing production and al1

locating resources insofar . as

th~

utility functions are as-

sociated with two-party .transactions.

But 'in connection with

waste disposal, the utility functions involve third parties,

and the automatic ~arket exchan<J:e process fails.,,21

THE GOVERNMENTAL APPROACH:

VARYING

DEGREES OF SUCCESS

It is this failure of the\market exchange process that

has precipated governmental intervention into the field of

water pollution control.

The PFocess . of effecting change

within the sy~tem has evolved .on many different levels with

varying approaches, and with these varying approaches have

10

corne varying degrees of success (as previously noted).

The

unifying factor has been that legislators have refused to conceive any new enforcement approaches and have stuck doggedly

with ~pproaches that have worked in the past in other areas,

with blind faith that they will work in the future.

These

\

approaches are best emphlified in two acts; the Federal water

Pollutioh "Control Act as amended,2,2 and the Rivers· and HarI

bors act of 1899 as amend~d.~ 23

'i

These acts, and their respec-

tive enforcement provisions,have·been the major tools of

congress and its enforcement agencies

~ike th~

Environmental

'"

Protection Agency in dealing

with the water pollution prob-

lem.

Each has stated objectives

or ~ enforcement

provisions

~

which makes obvious the goal o~ achieving a high standard of

\

water quality.

The first '·of these acts, the Federal Water

Pollution Control Act

point~

to this priority in section One,

the "Declaration of Policy," wherein it states, "The purpose

of this act is to enhance the

q~ality

and value of water re-

sources and to establish a national policy for' prevention,

control, and abatement of water pollution."

Further in the

act, at Section · 1 (B),.., it states,' "j..n consequ~nce of the

benefits resulting to the publlc ' health and welfare by the

prevention and control of water pollution, rt is hereby declared to be the policy of cong.ress to recognize, preserve,

and protect tpe primary ,responsibilities and rights ' of the

states in preventing and 'controlling water pollution,

,,24

11

Unlike the Federal Water Pollution Control Act the Rivers

and Harbors Act of 1899 has no declaration of po~icy but its

goals and objectives become obvious with a careful reading

of section 407 of the act, which states, "It shall not be

lawful to throw, discharge, or deposit or cause, suffer, or

procure to ~e thrown, discharged, ~r deposited either from or

out of any ship, barge, or ot.her floating craft ~fi any kind,

I

or from the shore, warf,

ma~ufa6turing

establishment,

~r

mills

'j

of any kind, any' refuse matter of.any kind or description

,, 25

whatever • • • , into any navigable water,

These two statements quoted from the texts of the respective acts

dra~atize·the

.almost

~niyersal

concern for the

quality of America I ~ water supply,' and · yet the effectiveness

I

~

of the two 'm ethods of enforcemen~ is severely limited and

hampered by the legislative construction of the enforcement

provisions, with net result of almost universal ineffectiveness of the acts. .IThe. two acts ...provide for approaches to the

problem of water pollution which are different' and the effectiveness of each will be analyzed t.o determine which is most

capable to deal with t?e

wat~r poll~tion prob~em

as it exists

in the United States.

THE FEDERAL WATER POLLUTION CONTROL ACT

The first approach

~hat

has been utilized is that of

abatement, embodied in section 10 (A) of the Federal Water

12

Pollution Control Act, and it states:

"The pollution of in-

terstate or navigable waters in or adjacent to any

stat~

• • • ,

which endangers the health or welfare of any persons shall be

,

~~

subject to abatement as provided by the

act." ~ -

This statement of determination seems at first to be a

clear statement directing action on a broad scale to restrain

polluters and pollution.

However, the last five words of the

f

quoted section are the limiting 'factor which has, up to this

point, and logically will in the future, limited the overall

effectiveness of the act.

The procedure of the act, which

must be followed, provides loopholes, and opportunities for

delay unequaled in, contemporary

leg;sl~tion.

The primazyloop-

hole in the enforcement provision ~s contained in section 10

(H), wherein it states:

"The court shall receive into evi-

dence in any such suit a transcript of the proceedings before

the board and a copy of the recommendations and shall receive

such further evidence as the

proper.

co~rtin

-

its discretion deems

The court, giving due consideration to the practcal-

ity and the physical and economic

abatement of any

pollu~ ion

proved,

~easibility

~hall

of securing

have jurisdiction

to enter such judgment and order enforcing such judgment, as

the public interest and the equities of the case require.,,27

This loophole, of magnificent proportions, allows wholesale disregard for the general policy of the act.,

Simply by

establishing a production' facility of enorrnouscost which re-

13

lies on, to a large extent, the use of water, either for production or waste disposal purposes, in such manner to ppllute the water, the industrialist avoids the necessity of complying with the provisions of the Federal Water Pollution

Control Act.

This f~ature is doubly true i~ light of provisions 10 (0)

of the act which relates to initiating action to bring about

abatement under the terms of the act.

vides in part:

Section 10 (0)

(1) pro-

"whenever requested by the governor of any af-

fected state or a state water pollution control agency, or

• • • the governing body of any municipality, the secretary

shall. • • give fO,r mal notification thereof to the water pollution control agendy • • • if any • • • and shall'call a

1

conference. ,,28

The significant language is, "whenever re-

quested by the governor of , any affected state."

This pro-

vides an immediate out for industries to locate in states

where the priority" for one , or C?ne of any number of reasons,

is on short run economic advantage as opposed to long term

ecological stability.

Without the request of the governor or

the state water pollutfon control

a~ency

or the governing body

of a municipality, the secretary has no means to enforce the

provisions of the act.

The immediate response to

~his

argument is two fold;

first, that the governor of a state, or the state water pollution control agency or the governing body ofa municipality,

14

has a more intimate knowledge of the problems and the requirements of that state's economic system, and should· there,fore

have the final veto over agency action to regulate the industry

that.is involved, as such regulation might have an effect on

the economy of that state; secondly that the provisions mentioned and referred to above apply only where' the water pollution problem is confined in

bot~

origin and effects to one

!

state, and it should therefore be up to that state to police

itself, without the interference of a higher governmental

agency.

In reply to this argument it should be noted that the

time has long since passed where either the economic system

or the problems of anyone state are confined in ultimate

effect to that state, and ' so with water pollution problems

and their effects.

If an economic problems arises within a

state, then its effect will determine, to some degree, the

policies and

progr~ms

their eco-systems.

lution.

of the other 'states in dealing with

The same is true in cases of water pol-

When one state sacrifices its vital water resources,

it places an additional burden on the water

jacent states.

r~sources

of ad-

"

While a governor might have intinate knowledge

of his state, it cannot be said that the water pollution problems of that state must therefore be automatically within his

exclusive "domain, it simply isn't, and this should be recognized.

15

Like the previously discussed loophole of requiring gubernatorial sanction to proceed under the terms of-the Federal

Water Pollution control Act, another road block to the effectiveness of the act is found in the second part of section

10 (D)

(1), wherein it provides that the secretary, at the

request of the governor or the designated agency shall call a

conference under the provisions of the act, " . . . . . unless, in

t

the judgment of the Secretary, the effect of such pollution

on the legitimate uses of the water is not of sufficient significance to warrant exercise of Federal jurisdiction under

this section.,,29

While 'it was probably the intent of congress ,

by including this phrase, to eliminate vexacious proceedings

when there is little' or no effect on the water regulated

under the terms of the act, the words chosen by congress to

impliment this intent do far more.

Not only does the secre-

tary have the power to refuse to pursue compliance with the

provisions of the

~ct

in the instances mentioned above but

also the secretary is cloaked with the power to make determinations, independent of any approved state or federal

water pollution standards, that a water pollution problem

doesn't exist in such substantial proportion to warrant action under the jurisdiction conferred by congress.

seemingly innocuous power

grant~d

This

to the secretary is para-

mount to that granted to the , governor of a state, or 't he

designated agency, to refuse to request action under the act,

16

for even if a governor or the appropriate state or local

agency were to request the initiation of procedures to bring

about abatement under the terms of the act, the secretary has

a veto, and can refuse on the; basis of his subjective determination that the problem is not of sufficient significance.

The fuhdamental stumbling blodk to effective action

under the provisions of the Federal Water Pollution Control

,

Act is that there are time requirements that are. unrealistic

in light of the urgency of the water pollution problem.

In

considering the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, as it

presently stands, it takes a minimum of twelve months before

the secretary can .initiate anything other than jawbone diplomacy to deal with industrial polluters of the public water

ways.

While there are undoubtedly examples of voluntary

compliance with the pollution standards that have been promulgated under the auspices of the act or because of the

secretaries

jawbon~

tactics,

mo~e

than likely this form of

voluntary compliance will not be forth coming from those polluters in industries which operate with high cost risk fac-

,

tors as an integral part of the industry struyture.

This

high cost risk factor makes voluntary compliance, on other

than an industry wide scale, economic suicide, and yet it is

in many cases these very industries that contribute to the

urgency of the water pollution problem.

In sum the Federal Water Pollution Control Act is fraught

17

with inconsistencies that make it's application difficult if

not impossible at times.

If the Federal Water ' Po~lutio~ Con-

trol Act is anything more than an example of the water pollution control acts that attempt to utilize abatement as the

att~mpts

enforcement device, if it does exemplify those

to

control water pollution, then the entire effort is doomed to

' less than spectular results.

If on the other hand· some of the problems of the Federal

Water Pollution Control Act have

~een

cured with additional

legislation or could be~ured with additional legislation

then abatement procedures would in fact be a significant tool

in dealing with the water pollution problem.

However, it is

the proposition of tbis writer that it' is a tool that is

\

best saved and utilized only as a last resort, for the effect

of abatement as is devastating on the industry involved as it

is dramatic in the results that it can achieve.

It should be

further remembered ,abatement does nothing about the pollution

that already exists.

In addition there is the ' problem that

systems like the Federal Water Pollution Control Act have no

power to generate operating funds and depend

~n

the gener-

osity of the congress to supply its operating capitol.

In

this respect legislation like the Rivers '· and- Harbors Act of

1899 have the advantage.

THE RIVERS AND HARBORS ACT OF 1899

Under the terms of the Rivers and Harbors Act much of

18

the operating capitol that is needed to make the program successful is made available through the fines that are imposed

on the polluters, secondly as much as one-half of the fines

that are collected goes to the individual that provides the

information necessary for the conviction of the polluter.

This second'provision that one-half of the fine goes to the

individual or group responsible

,

f~r

the conviction. has the

additional advantage that a 'much smaller enforcement staff is

necessary.

It should be stressed that because the Rivers and

Harbors Act has the advantage in these two respects that it

i J;Without disadvantages, or that it is the ultimate solution

to the water pollution problem.

\

Like the Federal Water Pollution Control Act the Rivers

and Harbors Act has

utilization.

disadvantage~

and obstacles to effective

The first of ' these obstacles is that the Rivers

and Harbors Act provides for fines that, while they might

have been appropriate in 1899

passed, are unrealistic today.

w~enthe

act was initially

While the fines may have been

a deterrent in the early 20th century when the united States

had a gross national product' on One Hundred Billion Dollars

"

.

'

today when the GNP is soon to exceed One Trillion Dollars, and

major industries regularly have net earnings' in excess of

Five Hundred Million Dollars it is hard to expect that a fine

of Twenty-five Hundred Dollars would have more than ' an annoying effect on a polluter.'

This is especially true when the

19

polluter is faced with the prospect of spending millions of

dollars in order to comply with the terms of the 'act.

This compliance with the terms of the act brings to mind

another problem, that being the setting of standards under

the Rivers and Harbors Act.

As the act stands there are no

standards by which to judge the actions of the polluters.

There are no definitions in the' act, thereby necessitating

,

the expenditure of large,'unrecoverable sums in proving that

there is a pollution problem or

t~e

extent that anyone in-

dustry or factory contributes to a pollution problem.

until

this problem can be solved, there is ' little prospect that the

administrator of t ,h e Environmental Protection Agency, in effect the alter ego of the government in matters concerning

the environment, will undertake expensive litigation in cases

where the question will be difficult.

An additional limiting factor on the effectiveness of

the Rivers and

Har~ors , Act

of

1~99,

is found in Executive

Order 11574, which deals with the Rivers and Harbors Act.

Section one of the Executive Order provides for a system of

,

permits to allow industries to deposit waste products in the

waters that are subject to the · provisions of the act.

Sec-

tion Two (A) of the Executive Order, by using inverse logic,

implies that such a permit shall be issued when section 21

(B) of. the Federal Water Pollution Control Act has been complied with.

Section 21 (B) of the Federal Water Pollution

20

control Act provides that:

• shall provide

"Any applicant

the licensing or permitting agency with

a

certificatio~

from

the state in which the discharge originates or will originateA • • • that there ' is reasonable assurance, as determined

by the state

.' that such activity will be conducted in a

manner which will not violate the applicable

standards."

fac~s ~ the

This provision

~ater quality

same difficulty that was

I

faced by the Provisions of the Federal Water

Pol~ution

Control

'j

Act that were mentioned previously, in that it is up to the

state to make the deter~ination that a industry or factory

will be subject to the provisions of" the act.

If the state

.

has made the determination that it will sacrifice long run

,

'

ecological stability for short ruri economic gain then. there

\

is little if anything that,can

b~

done to prevent the pollu-

tion, except that the administration of the EPA can veto, a

power discussed earlier.

The net effec-ty. of,the,

prov~sions

outlined above is·that

the Rivers and Harbors Act is fa?ed with many of the same difficul ties that faces the Federal',Water Pollution Control Act,

in some cases out of necessi~y' in · that it uti~izes many of the

' .'

same provisions, and in some cases makes direct reference to

the Federal Water Pollution Control Act.

Orr the other hand

the difficulty arises in part because the Rivers and Harbors

Act is a product of the same limited in scope thinking that

produced the Federal Water Pollution Control Act.

Both acts

21

are devoid of a dirth of creative thinking so necessary if

there is to be an approach developed with any rea~onable

chance of success.

This is not to say that all of the pro-

posals that are incorporated in the two acts are ineffective

but only that the methodology through which they have been

employed lacks the requisite creativity to make the acts effective tools to deal with the pollution problem.

SOME CLOSING OBSERVATIONS

Perhaps the most eloquent statement of what is needed to

effectuate change within the present structure under which

polluters have found an apparent haven in which to operate

appeared in the message of the President of the United States

outlining legislative proposals and administrative actions

taken to improve the environmental quality,. wherein he stated,

"I propose that we take an entirely new approach:

one which

concerts Federal, s~ate .'and private .efforts, which provides for

effective nationwide enforcement, and which rests on a simple

but profoundly significant principle:

waterways belong to us all,

,

nor an industry should be

~nd

that the nation's

that neither a municipality

allo~ed

to discharge wastes into

those waterways beyond their capacity to absorb the wastes

without becoming polluted."

It was at this point that the President outlined a series

of proposals to effectively deal with the water pollution