18 Chapter THE LANGUAGE OF NON,ATHENIANS IN OLD COME,DY

advertisement

Chapter18

THE LANGUAGE OF NON,ATHENIANS

IN OLD COME,DY

Stephen Coluin

I

In Nicolas Roeg's fim The Witches,la comedy-thriller aimed at children but

equally enjoyablefor grown-upS,Anjelica Huston plays the evil and glamorous

chief witch, whose wicked plan is to turn all children into mice (the film is

an adaptation of Roald Dahl's book of the same name). The action is set in

England and Norway; the child protagonist is an American with a Norwegian

'What

is striking is that, in this slightly mixed ethnic setting,

grandmother.

Angelica Huston plays her role with a heavy and gratuitous German accent,

addressingher cat ('familiar') as mein Liebchen,and so on. The conclusion to be

drawn, though unpalatable, is unavoidable: the makers of the film (following

'phonetic'

spellings such as

Dahl's original text, which is characterizedby

Inkland) felt that at the end of the twentieth century it was still part of the

'baddie'

could be

dramatic convention of English-languagecinema that a

marked with a German accent - even when there is no dramatic reason for

a German characterto be introduced. The use of marked language(i.e. forms

which are felt to be linguistically deviant) to associateliterary characterswith

particular moral or intellectual qualities hasa long pedigreein English literature:

one need only think of Dr Caius (A French Physician) or Sir Hugh Evans

(A Welsh Parson')in Shakespeare's

Merry Wiues.Since a certain tribalism seems

to be built into the human way of looking at the world, even if it may have

ourgrown its evolutionary usefulness,and since linguistic variation is one of

the easiestways in which one social group may mark itself off from another

(or be defined by another), the associationof language and ethics in literary

activiry is common in cultures acrossthe world. Nevertheless,the claim of this

'linguistic

universal'is weakenedby the wide variations

phenomenon ro be a

which are found in the practice. First, it is clear that the extent to which

languageplays a role in ethnic identity, and the associationof moral or other

are sociopoliticalissues,and will

with linguistic characteristics,

characteristics

reflect the prevailing ideologiesof the communiry. Secondly,literary form and

convenrion vary from culture to culture, and this will influence the presentation

of linguistic variery and deviation.

285

StephenColuin

\fhen we examine the presentation of linguistic variety in Old Comedy we

are naturally inclined to find a range of meanings similar to that which we

'we'

anyway?Modern

might expectto find in our own comic literature (who are

western literatures are by no means uniform on this point). In defenceof this

approach one might advance(i) the frequent (supposedlyuniversal)association

of out-group languagewith negative characteristics,and (ii) the link (whether

conceivedasgenetic or ideological)berweenancient Greek and modern western

culture. \7e need not spend too long on (i) in view of the caveatsraised

above,and especiallywhen we consider that even within the history of English

literature the implications of dialect and non-standard languagehave changed

from period to period: it is not clear,for example,that the northern dialect of

the students in Chaucer'sReeudsThle is a target of ridicule or censure;and in

D.H. Lawrencedialect may be a sign of spiritual integriry.The link in (ii) is

more interesting:it is undeniablethat aspectsof political thought and literary

'inherited'

from classicalantiquiry by the modern world,

convention havebeen

including perhapsthe notion of barbarismoswithwhichthe Greek and later the

Roman world sought to define itself in the faceof alien cultures.A nice example

of the projection of later attitudes to dialect and language on to the ancient

world is furnished by the lusciousopening sceneof Flauberr'sSalammbf, the

banquet of the army of Hamilcar:

cehiquesbruissantes

On entendait,h cbti du lourdpatois dorien,retentirlessyllabes

du

ioniennes

selteurtaientaux consonnes

commedescharsdebataille,et lesterminaisons

disert,hprescommes

descrisdechacal.

Sideby sidewith the heavyDorian patois,Celtic syllablescould be heardringing

and Ionian terminationscameup againstthe

out, clatteringlike battle-chariots,

harsh

of

the

desert,

as

the

cry of the jackal.2

consonants

'When

we consider, however, that the ethnic and linguistic jokes of Old

hardly

survived into the Middle period of that genre, partly owing

Comedy

to changed social and political circumstances,and partly no doubt because

of developments in literary taste, it becomes clear that modern intuitions

about the comic potential of foreigners and barbarians should be tested very

thoroughly against the availableevidence.This is particularly important in

the case of Greek dialect, firstly becauseattitudes towards the dialects seem

to have changed radically in the Hellenistic period (owing to the spread of

the koine), and secondly because,owing to the peculiar political and cultural

structureswhich underpinned them, the dialectshad no real equivalentsin the

Roman or medieval worlds.

II

The role of marked languagein the fragments of Old Comedy is often difficult

to evaluateowing to the loss in most casesof the dramatic context. There are

rwo problems in particular: (i) without the immediate context it is difficult to

286

The languageof non'Athenians in Old Comedy

seewhether a form which looks like Doric or Ionic indicatesthe presenceon

srageof a foreigner,or is (for example)paratragic;(ii) evenwhen a foreigner can

be identified with certainry without the larger dramatic context it is difficult

to see what sort of role the character is playing, and hence what effect the

linguistic marking is supposedto have.There is a further, practical worry: nonstandardlanguagesuch as dialect is vulnerable to scribal corruption, and this is

particularly seriousin the caseof fragments,which are typically short quotations

taken out of context (cf. Arnott in this volume, PP.2-3, and Page195I,103).

Seriouscrucesare noted without comment in the following discussion.

Given the parallels which Aristophanic and Menandrean drama provide,

a list of porenrial dramatic situations for the exploitation of non-standardAttic

might include the following:

(a) Barbarianson srage,speakingeither unmarked or barbarizedGreek;

(b) Slanderedpoliticians on stage,speakingunmarked or barbarizedGreek;

(c) Non-Attic Greeks on stage, speaking in dialect, or unmarked Attic, or

conceivablybarbarizedGreek;

(d) Slavesand rustics, speaking unmarked Greek, or dialect, or barbarized

Greek, or substandardGreek;

(e) 'Stock' figures such as the Doric-speaking doctor on stage.

If we can match the fragments against the above list it may be possible in

somecasesro userhe Aristophanic parallelsto fleshout the dramatic possibilities.

Although the titles of plays which have not survived give a good idea of the

fascination exertedby the foreign on Old Comedy, they do not necessarilygive

much indication of the potential for charactersspeakingnon-standard Greek in

the plays:titles such asHelots,Lydians,ThracianWomen,Laconiansetc. (Eupolis,

Plato, Nicochares, Eubulus) are obvious candidatesfor foreign characters,but

we need only consider the Aristophanic titles which actually contain extended

to

passagesin non-standard Greek (Acharnians,Qristrata, Thesmophoriazusae)

realizehow deceptivethe exerciseis likely to be.

(a) Barbarians

In the Aristophanic corpus two types of Barbarian speech have survived:

occasionalrepresentationof Barbarian language(i.e. gibberish, as at Acharnians

100),3and (morecommonly) barbarizedbut intelligibleAttic. No clearexamples

of barbariansspeaking barbarizedGreek have survived in the fragments of the

Rivals.This is not surprisingin view of the natureand purposeof the quotations

in which mosr comic fragments have survived: later writers interestedin Attic

terminology were unlikely to be interestedin quoting barbarizedGreek,whether

they were literary in inclination (Athenaeus) or grammatical (Apollonius

Dyscolus). That the humorous treatment of foreignersand their languagewas

as popular with the other comic playwrights as it was with Aristophanes is

indicated only obliquely in the fragments, by the preservation of occasional

'air'

in Philyllius fr.1.9.1' €l.retv to Be6u

glossessuch as the Phrygian BeSu

287

StephenColuin

orrlrqptovnpooerilopar ('I pray that I may breathedeep the healing air'): this

does not appear to be part of a rendering of barbarized Greek, but seemsto

involve useof a Phrygian glossto give a mystic (perhapsOrphic)a flavour to the

speechof an Attic-speaking character,who is no doubt being mocked for this

display of alazoneia(pretentiousness).

If plays with titles like Lydians and Thracian Women contained foreign

characters,it is worth reflecting that the roles played by charactersspeaking

barbarized Greek are unlikely to have been substantial (the longest extant

since short

example is the Scythian archer at the end of Thesmophoriazusae),

scenesextracting humour from barbaric Greek will have been more in keeping

with the spirit of Old Comedy (compareDover'sprinciple (1976187,238) of

one joke at a time) than extendedrepresentation.If such playswere named after

their choruses,the foreign characterizationis likely to have consistedof hoots,

ululations and unusual glossesrather than faulry phonology or morphology,

perhapslike a comic version of the chorus in Aeschylus'Persians.5

A fragment (83) from the Metics of Plato Comicus may contain a solecism

which Plato put into the mouth of a foreign character(a residentalien?),but

the absenceof context makes this no more than a guess.Apollonius Dyscolus

warns that one cannot use the nominative of epouto0 (i.e. epout6q instead

of eyrirout6g), adding that it is found in the Metics iooq €vero toO yel"oi.ou,

'perhaps

for the sakeof a joke'.

(b) Comic Slander

The practice of ascribing barbarian and/or servileorigins to one'spoetic victims

is alreadyevident in archaic song (e.g. Anacreon 388), and all the surviving

referencesto barbaric speechin the comic fragments come from this rype of

'real'

context rather than one involving

barbarians (the distinction is slightly

tricky in view of the Persian in the opening scene of Acharnians, who has

a rather fluid identiry). In Old Comedy the poetic victim is most often a leading

politician (cf. MacDowell 1993 and Sommerstein in this volume), and the

rwo most popular candidatesfor lampoon in the fragments are Cleophon and

Hyperbolus: it is worth noting that most of our information on the activiry

of Aristophanic rivals in this regard comes from scholia on passagesin the

Aristophanic corpus where these two politicians are under attack. At Frogs

679-83 the chorus singsof Cleophon

eQ'o0611

letl,eotv oprQrl,dl"orq

8ervdventBpepetat

@plria 1el,t6rrlv,

eni BdpBopov

e(opevqnetol"ov

lips the Thracianswallowshriekshorribly,perched

...upon whosedouble-speaking

1996,214).

on barbarianleafage(cf. Sommerstein

288

The languageof non-Atheniansin Old Comedy

A scholiast ad loc. tells us that Plato Comicus in his Cleophonportrayed

the politician'smother speakingbroken Greek to him (fr.61: popBcpi(ouoov

'Thrassa'.

A scholiaston Clouds

rrpoqoutov) and notes that she was called

the

same with the mother

much

did

in

Artopolides

552 saysthat Hermippus

Maricas in

the

pseudonym

of Hyperbolus, a politician who starred under

Eupolis'play of the samename (Lenaea,42I: seeSommersteinin this volume,

pp.440-2). Fragments from this play (..g. 193) indicate that Hyperbolus

himself did not in fact speak barbarized Greek: the playwrights seem to have

portrayed him as a cultural rather than a linguistic barbarian, qypical perhaps

of the new classof politician. Quintilian (1.10.18), after identi$'ing Maricas

explicitly with Hyperbolus, saysnihil se ex musicisscire nisi litteras confitetur

('he admirs thar he knows nothing of the liberal arts exceptfor the alphabet'),6

which suggeststhat the character was a coarseupstart similar to Cleon in

Knights. It is interesting here to compare a fragment (183) from Plato's play

Hyperbolus,quoted by the grammarian Herodian, who was interested in the

phonology:

trlv civeutoOy 1pfrotvdlqBdpBopov,

lll.rirov pdvtot ev'TnepB6l,rrl8tenatfe

l"eyrrlvoiJtroq'

o 6'ou yop qttirt(ev, 6 Moipot Qtl'ot,

"

"

al.l"'on6te pdv lpeiq 6t1tropr1vl"eyetv,

",

"

€Qoore 61tropr1vofiote6' eineiv 6eor

">

",

"

..

ol"(yov <"ol.tov d),eyev.

asfollows:

mockedthe droppingof g asbarbarous,

Platohoweverin hisHyperbolus

"He didnt speakAttic, ye Fates(Mo0oat (Muses)ci. Meineke),but whenever

he

had to saydiatamenhe saiddjetamen,and when he had to sayoligoshe cameout

wrtholios..." .

'barbarous'

appearsin the mouth of the grammarian,not

While the adjective

the playwright, it certainly looks as though a notion of attikismosis already at

work here in the lampoon of the politician. The barbarousor (to avoid begging

a question) marked Greek looks like a substandardsocial variety ('sociolect')

rather than an attempt to representthe idiosyncratic Greek of a foreigner (for

Now it should be clear

which compare the Scythian in Thesmophoriazusae).

that a dialect or sociolect is not judged with value terms such as pleasant,

'aesthetic'

grounds; our judgment on

harsh,vulgar, etc. on purely objectiveor

such matters is coloured by political, social and ideological factors. For the

ancient Athenians, for example, a Laconian accent will have triggered a range

basedon Athenian perceptionsof Laconian socieryand history

of associations

(anyone familiar with a range of Greek literature will realizethat by no means

all of the associationswill have been negative,and that Flaub ert'slourd patois basedperhapson belleipoquescorn for Spartancultural achievementin the face

of a romanticized view of Athens - is likely to have been closer to Athenian

attitudes towards Boeotian). \7e can have a h"ppy time speculatingwhy it was

289

.-

StephenColuin

a bad thing for a politician to speak the substandardAttic that Plato accuses

Hyperbolus of coming out with. For example,one of the very few referencesto

a socialvariery ofAttic occursin a fragment of an unknown play ofAristophanes

'the

(K-A 706 = 685 Kock) quoted by Sextus Empiricus:

grammarians say

that...the ancientAthenian idiom is different againfrom the modern one, and

the idiom of those who live in rural areasis different from that of city dwellers.

"

Concerning which Aristophanesthe comic poet says: [his] languageis the

normal dialect of the city - not the fancy high-society accent, nor uneducated,

rustic talk"':

...roi. ou1 q outrl;.revt6v roro trlv oypotriov, 11ouq 6e tdv ev ciotet

l,eyetAproroQdvqq'

6totptB6vtov.noporoi o KopLKoq

IXOPOI?]

6td]"ertov61ovtop€onvno].eoq

otit' ooteiov uno0ql.ut6pov

o'iir'ovel"eu0epov

unoypotrorspov.

Since, then, we appear to have evidence for a popular awarenessof rustic

language we might suppose that Hyperbolus' speech is mocked by Plato for

featureswhich recalled the language of the Attic countryside. This seemsan

unlikely assumption.The evidencefrom Old Comedy points to a vision of

the Attic countryside which was, on the whole, regardedas a repository of

positive ideological values: although the Acharnians can be stiff-necked and

quick-tempered,it is their gullibility that inclines them to support the foreign

policy of a sleazypopulist in the ekklesia rather than a shared sleazinesswith

its roots in the countryside (after all, the urban massesare inclined to make

the same mistake, but this lends itself more easily to the plot of Knights or

The featuresof Hyperbolus'speechpicked out for comment are ones

Wasps).

'sloppy'

speech,since they appearto be the result of an

which could count as

attempt to minimize the effort of articulation: the pronunciation of 8rrltrrlprlv

and o),iyov which Plato attacksmay have been approximately'd(i)slomer'7 and

'oli(y/y)on'.

'low

It seemsmore likely that Hyperbolus' substandardis a

urban'

'international'

Attic

rather than a rural variery of Attic: perhaps the nascent

of the ciry which was also attacked by the Old Oligarch (ps.-Xen.Ath. Pol. 2.

7-8, perhapswritten c.425 nc8) and which culminated in the koin1. If this is

true, it is worth remarking that a rype of Greek which is likely to have been

heard quite commonly on the streetsof Athens and Piraeuseis characterized

by the playwrights (at least implicitly, and perhaps explicitly) as barbarous a character with a Thracian mother revealshis low background by his low

morals, his deficient paideia, and his substandardGreek.l0

The category of slandered politicians, then, involves a double senseof

'barbarous':

the first and most obvious is the common accusation (by no

means restricted to comedy) that non-citizen blood in a particular public

figure disqualified him for political office or public influence. The second

290

The languageof non-Atheniansin Old Comedy

senseintroduces the notion that a particular figure comes from a low social

background and is therefore not fit to be a member of the ruling classdue to

lack of an appropriate education and (if this can be distinguished) the inherent

criminaliry of his milieu. For this ideacompareDemosthenes'tauntsat Aeschines

in the De Corona(Demostheneshad a liberal education,while Aeschinesworked

asa second-rateactor,etc.). Demostheneshimself,coming from a'good' family,

was nor open to this line of abuse,but was the target of accusationsthat he had

barbarianfamily connectionsfor variouscontorted reasons.r'

It is worth remarking, finally, that there are no fragmentsin which a slandered

with a non-Attic dialectof Greek:they areeither no-good

politician is associated

Atheniansor barbarians.

(c) Non-Athenian Greehs

The depiction of non-Athenian Greeksin the comic fragmentsis particularly

difficult to analyse,since as a result of the absenceof dramatic context we

generallyhave no idea of who is speakingthe fragmentary lines that have been

preserved.It is the presenceof dialectwhich alertsus to the presenceof a foreign

speaker,and this leadsto a dangerof circulariry.Neither is it possibleto tell from

fragments whether any of the comic playwrights introduced non-Athenians

speakingperfectAttic, nor whether they everpresentedsuchcharactersspeaking

Greek marked not with dialect forms but with barbarisms(such as epoutdq

in (a) above).Thus, for example,a fragment of Eupolis (341, unknown pl"y)

preservesthe line pn rpnxuq io0r ('Don't be difficult') where the Ionic form

rpnxuq might lead us to think that an Ionic characterhas been introduced. On

the other hand, the form is found at Peace1086 in pseudo-Epicdiction as part

of a parody of oracles.The most significantsnatchesof dialectare lines or short

'choral'

Doric does turn up in Old

in Doric and Boeotian.Although

passages

if

Comedy (in the parodosof Clouds,for example), one has more than a single

word it is generallymuch easierthan in the caseof Ionic to be sure that one is

dealingwith representeddialect rather than a lfterarylparodicform.

Doric dialect can be divided into rwo categories:Laconian and the rest.As

a superpowerdialect it is clear why Laconian should have a high profile in

comedy: of the other Doric dialectstoo little remainsfor us to be able to tell

how sharply they were distinguishedfrom eachother and from Laconian.The

longest fragment, fr.4, comesfrom Epilycus' Coraliscus:

nottav ront6',oi6, o6irat.

ev Apurl"ototvt nop' Anel,l,crt

Boporeqnol"l.oirciptot

rai 8orpoq

tot ;rol.oobuq...

I reckonI'll go to the Kopislfestival].In Apollo'splaceat Amyclaethereareplentyof

anda broththat'sreallygood...

andwheatenloaves,

barley-cakes,

In this short passagewe are able to seethat it is not lexical items alone that

29r

StephenColuin

characterizethe dialect. The phonology is in line with Laconian, and also the

syntax (in nop' Andl.l.ro,where an accusativereplacesa dative). It is striking that

the rendering of dialect featuresin these lines (as in other, shorter fragments)

appearsto be at the same level of accuracyas Aristophanes' fairly convincing

rendering of Laconian in Lysistrata.l2There are other fragments of Doric where

it is impossible to guesswhich dialect is being represented(e.g. one line of

Philyllius' Cities, fr. 10); while a line from Apollophanes' CretAns(fr.7) may

have been spokenby one of the eponymousislanders.

Athenaeus quotes a three-line fragment (fr. 11) from Eubulus' Antiope

(c.380?) which is clearly uttered by a Boeotian. Enough survives for us to

be able to tell that the Boeotian dialect is renderedrather lesspreciselythan

the Laconian of the fragments,which reflectsthe situation in Aristophanes'

Acharnians quite closely (Aristophanes'Boeotian is not rendered as accurately

as his Laconian or his Megarian).This may be becauseBoeotian had a greater

proportion of peculiar featuresthan other dialectsto an Attic-speaker,t'which

would have been inconvenient and unnecessaryto representon the stage:the

playwrights merely had to pick out a convincing number of salient features

to identify the dialect to the audience. A well-known passagefrom Strattis'

PhoenicianWomen (fr.49) seemsto attack the Thebans for the peculiarities

of their dialect:

n6l"tq,

luviet' ou66v,ndoa OrlBoirrlv

ou6i:vnot'cil.),'.o'i np6tc pevtrqvoqnfov

ontr0ottl,av,rilgl,eyouo',ovopti(ete...

Firstof all,

nothing,all you peopleof Thebes,nothingwhatsoever!

You understand

a

cuttlefish

opitthotila...

theysaythat you call

continuesin this vein for eight lines,highlighting the phonological,

The passage

morphological and (ashere) lexical differencesbetweenAttic and Boeotian.

The evidencefrom the fragments suggeststhat Aristophanes' use of dialect

on rhe stagewas not unusual. The playwrights seem to have known enough

about the other Greek dialectsto representthem convincingly, from which we

can draw some conclusions:(i) we are not dealing with an artificial literary

'rustic'

dialect found in some English

dialect (such as the comic west-country

from a literary tradition; (ii)

inherited

merely

literature)which the playrvrights

there is no evidencefor confusion beween literary Doric and real Laconian; and

(iii) so far as we can tell, the humour extractablefrom putting foreign Greeks

on the sragewas not basedon dialect pastiche (i.e. inaccurateor barbarizing

representationof dialect,or substandardAttic).

(d) Slaues,rustics,mechanics

Although many slavesin Athens were foreign (either Greek or barbarian), and

slaves'names such as Thratta ('Thracian girl') turn up in comedy, it does not

seem to have been part of the convention of the comic stage to characteize

292

The languageof non-Atheniansin Old Comedy

slaves'language as foreign.la This is perhaps best explained in terms of their

dramatic role: their foreign-nessis not important for the comic drama, and is

not emphasizedlinguistically. An obvious exception is the Scythian archer in

who speaksbarbarizedGreek the reasonfor this is perhaps

ThesmophoriAzusae,

connected with the unusual behaviour permitted to this body of public slaves

(such as certain powers of corporal restraint over citizens). It seemsalso to

emphasizehis stupidiry and to help in the reconciliation of the two estranged

citizen groups (Euripides'team and the women). It is tempting to seea reference

to the linguistic difficulry causedby a householdslaveof foreign origin infr.74 of

Pherecrate

s' Corianna,quoted by Athenaeusto illustrate the name of a fig:

A:

o).1"'ioXri8oqpol np6el"etdv rueQrrlyp€vov.

[roi pet'o].iyo6e'l

our iolti8og oioetg;tdv pel.otvdv;pcvOdvetq;

ereivotqBopBopotq

[?B:] ev toiq Moptov8uvoiq

y'6rpac,

rol,o0ot taq pel.oivoqio1d6oq.'5

Fetchme someof the toastedfigs![anda little furtheron] \fon't you fetchthe figs?

Among thosebarbarianMariandynithey call

The blackones!Do you understand?

figs'pipkins'.

blackened

The last rwo lines (perhapsspoken by a second parry) look like an explanation

of the slave'sinaction in terms of a failure to understand the Greek, but since

the slave'sown words are not preserved (if there were any) it is difficult to

comment on the linguistic characterization:as the passagestands it looks

like a comic version of the scenebetween Clytmemnestra and Cassandrain

Aeschylus'Agamemnon.The abuseof stupid and incompetent slavesis in any

casea perfectly normal ingredient of Old Comedy.

The absenceof any convincing parallelin Old Comedy to the rustic English

'Pyramus

and Thisbe' scenein Midsummer Nighti Dream was

of Shakespearet

touched on under (b) above:apart from the specialcaseof sleazypoliticians,it

was not in the interest of the playwrights to focus attention on the low linguistic

habits of a particularpart of the citizenpopulation (the foppish Ionicismsof the

jeunesse

dorde,td perportq...tov t0 puprp('the young men who hang out in the

perfume shops',Knighx I375-81) were a safetarget). It would be interesting

'Piraeus

Greek'

to know if metics could be characterizedwith a low variery of

similar to the politicians,but the evidenceis lacking.

(e) 'Stock'figuressuclt as tlte Doric-speakingdoctor on stage

Stock figures such as the foreign doctor are particularly associatedwith the

later development of comedy in the fourth century, the best-known surviving

example being in Menander's Aspis 439-64. However, the gap between the

foreign doctors that we hear were typical of early Doric farce (Athenaeus 14.

62ld) and the later stock figures of Middle and New Comedy is filled by an

instance from Crates, who, according to Aristotle (Poetics1449b5-9) was the

293

;

StephenColuin

'plots

of a generaland non-personal

first of the Attic comediansto move towards

narure' (sincedoctors were notorious for fraud and incompetence,it may be

that the dialect markers pointed not only to professionalbut also to moral

character).Fragment46 of Crates(from an unknown play) is a line in medical

Doric: ol,),o otniov notrBo),6 tot roi rr) ),r1qonooldoro ('...but I shall apply

my cup, and lanceit too if you like'). We havealsoa likely Ionic-speakingdoctor

(or impostor) in a fragment of Ameipsias' Sling (Sphendone,fr.17) quoted by

Athenaeus:l.oyov ropci(oqni0t tdv Ool.tioorov('Stir in the hare of the seaand

drink'), where the markersof Ionic arethe word l.cy6q (the object ofAthenaeus'

commenr) and the -oo- in Ool"cioorov.These two examples illustrate that

already in the fifth century dialect could be used to identify a stock character,

which is not a situation one might have guessedon the basisof Aristophanes'

surviving work, where the prevailing iopBrrq i6eo (the comedy of invective,

or lampoon) is such that specific individuals only are presentedspeakingin

dialect, and the dialect indicatesprovenancerather than professionor moral

character(of course,Thebans may be hated and consideredstupid, but this

does not mean that any hateful or stupid characteris for that reason given

of medical Doric or Ionic

aTheban accent).If we had a more extendedpassage

it might be possibleto tell whether the dialect is intended as a representation

of a real epichoric dialect (Coan, for example),orwhether it is merely'generic'

Doric/Ionic, basedon a mish-mashof dialect features.

..

..','.**-.-..@

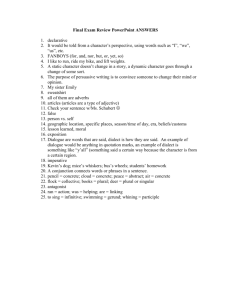

Fig.7(b).

Fig.7(a).

294

The languageof non-Athenians in Old Comedy

m

The fragments confirm that there was in Old Comedy enormous scope for

marking up languagefor various dramatic effects.This is a feature shared by

modern comic and light-hearted drama, perhapsby coincidence,or perhaps

becausethe humorous manipulation of languageis universallyfound in such

'W'hatever

contexts.

the truth of this, it is worth noting some of the specificways

in which linguistic jokes in Old Comedy work, for this seemsto be very closely

tied to particular culturesand political circumstances.

The inadequatecommand of Greek by foreignerswas clearly considered

a legitimate source of mirth by the Greeks, as by many moderns, despite

Fig.7(a). The New York Goose Play

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Callx-krater by the trporley

Painter,painted in Thrasc.400 ec. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 24.97.104.

Height 30.6cm.

(b) Policeman on the Beat?

Detail of the New York Goose Play.

An old man standsin the middle, naked (i.e. wearing a padded body-stockingwith comic

phallos) and on tip-toe, with his arms stretchedabovehis head. He saysKATEAHIAN'He

OTOXEIPE,

has bound my hands up', and looks apprehensivelytowards a younger,

uncouth-looking man on the left. He too is naked, holds a stout stick, and is saying

NOPAPETTEBAO. On the right an aged woman on a stage-likestructure extends her

'I

arm and saysEfC)IAPI-EEO, will hand <him> over'. In front of her lie a deadgoose,

two(?) kids in a basket,and a mantle. At the extreme left standsa smaller figure, labelled

TPAfOIAOI, whose stiff posesuggestsa statue;a comic mask floats in space.

It is generallyagreedthat the old man must have stolen the objects on the right, and

'The

that he is about to be beaten by the younger man as a punishment for his theft.

'has

man with the stick', saysBeazley,

disorderedhair and a rough face;and what he says

is not Greek. He has alwaysbeen recognizedto be a barbarian, a foreign policeman or

the like.' It is not clear why he is naked: perhaps his clothes (including the mantle) are

'The

among the stolen goods.

senselof NOPAPETTEBAO] is dark', Beazleycontinues.

'Characters

in Aristophanesmay speak (1) dialect Greek, or (2) pidgin Greek, or (3)

a foreign language,or (4) make noisesthat sound like a foreign language.This seemsto

be either (3) or (4).' In that case,this scenefrom an unknown play by a contemporary

of Aristophanesforms a fascinatingvisual complement to the literary evidencediscussed

by StephenColvin in this chapter.

But the old man'shands are not tied, and Beazleyseeshim as the victim of a binding

spell, a hatadesis(defixio): he is literally spell-bound. Could NOPAPETTEBAO be the

words of the magic spell?If so, the man with the big stick need not be a barbarian.

'The

"Phlyax-Vase"'

BeazleyJ.D.

New York

, AJA 56 (1952) 193-5 with pl. 32.

Gigante M. Rintone e il teatroin Magna Grecia,Naples l97I,7I-4.

Thplin O. ComicAngels,Oxford 1993,20,30-2,62; bibliographyat ll2-3 (the mo

items listed aboveare the most helpful); plate 10.2

295

StephenColuin

evidence that the Greeks themselveswere lazy at learning foreign tongues

(Momigliano 1975, ch.1). There is also evidencethat villains (politicians)

could be associatedwith substandardGreek. The implication that a speaker

of this substandardGreek lacks an appropriate Hellenic paideia may point to

its associationwith a low socio-economicbackground;such charactersare also

rourinely given barbarous family connections.Apart from this special case,

however,we do not find much evidencefor the comic spotlight being turned

on linguistic differencesberweenthe various socialclassesin the citizen body or

even berween citizens and slaves.The small amount of dialect which survives

suggeststhat dialect alone was not used to attack: other Greeks might be

hated for various reasons,but the fairly careful depiction of non-Attic dialects

indicatesthat they do not seemto have been representedasspeakinginadequate

or substandardforms of Greek. This is in sharp distinction with many modern

western literatures, where before the nineteenth century dialect was routinely

treated as a substandardvariery of the standard language.

Acknowledgement

I am gratefulto David Harveyfor manyhelpfulcommentson this Paper'

Notes

'

Films1990.

Ji- HensonProductions/Lorimer

2 Thesecharacteristic

wereusingincluded,

terminationswhich the Ionianmercenaries

in -tr6g and the abstractnounsin -otq which beganto

the adjectives

presumably,

invadethe old Attic languagein the fifth century(for the comic potentialcf. Knights

r375-8r).

3 There havebeen attemptsto make senseof this passage(seee.g. Dover 1963,7-8 =

'gibberish

made from Persiannoises'

1987,289-90).It seemsto me most likely that it is

('West1968, 6). Seealsothe discussionby Morenilla-tlens 1989.

a Cf. the conrext of the fragment: Clement of Alexandria Strom. 5.46.3-6, printed

in K-A ad loc.

5 Frogs 1028-9 with Sommersteinad loc. (1996, 247), Hall 1989, 83-4 and Hall

1996,23,152-3 with the quotation from Cavafr facing the title-page.Cf. Ar. Babylonians

fr.81 K-A = 79 Kock fr nou roto oroilouq rerpd(ovtct tt popBoptoti,'standing in

formation they'll screamsomething foreign - a referenceto a similarly constituted chorus,

and Ar. Danaidesfr.267 K-A = 253 Kock.

6 A similar boast is made by the sausage-seller

at Knighrs 188-9.

7 Cf. 'Woody Allent worry in Annie Hall that one of his colleaguesis saying 'Jew eat

'D[id]'

you eat yet?' (United Artists 1977, dir.'Woody Allen).

yet?'insteadof

s The date is controversial:see the literature cited by Mattingly 1997, who himself

arguesfor a later date (414).

o ..g.for ol,ioq seeThreatte1980,440 andTeodorsson

1974,266.

10 See Cassio 1981 and Brixhe 1988 for the connection between low-prestigeAttic

and the rype of mistake attributed to foreigners.At Clouds 876 Socratesimplies that

296

The language of non-Athenians in Old Comedy

Hyperbolus was launched into public life as the result of a sophistic education which

remedied his deficient education and disagreeablelinguistic habits.

" Demostheneson Aeschines:18 (deCorona)258-52,265; Aeschines

on Demosthenes:

3 (In Ctes.)L7I-3.

12 Dialect evidencecan be checkedin the standardhandbooks,such asThumb-Kieckers

1932, or Bliimel 1982. There is a brief discussionof Aristophanic accuracyin Colvin

1995,with a fuller accountin Colvin 1999; seealsoHarvey 1994, Svi.

13 See Coleman 1963 for a statisticalanalysisof shared featuresamong the Greek

dialects.

'a The scholia at Knights 17 see td Opdtte as a barbarism characteristicof a slave

(Opette ydp BopBcptrdq to Ocppeiv. Bappapi(et 6e rig 6o0l"o9). Opetre looks like

slang(so Sommerstein1981,145 ad loc.), but is more likely part of a low socialregister

than a barbarian idiom.

'5 People complain about the languageof their servants,but may in fact prefer

a distinction to exist;seePlato Laws777cd and Aristotle Pol. 1330a25_.8on the unwisdom

of having slaveswho speak the same dialect as their masters,and cf. George Orwell's

'Dont

"I

expatriate businessmanin colonial Burma:

talk like that, damn you find it

"Please,

very difficult!" Have you swalloweda dictionary?

master,can't keeping ice cool" .We

that's how you ought to talk.

shall have to sack this fellow if he gets to talk English

too well.' (BurmeseDays ch. ii, New York 1934).

Bibliography

Bltimel\W.

1982

Die aiolischenDialekte, Gottingen.

Brixhe C.

'La

1988

languede I'dtrangernon grecchezAristophane',in R. Lonis (ed.) L'Etranger

dansle mondegrec,Nancy, 113-38.

CassioA.C.

'Attico "volgare"

1981

e Ioni in Atene alla fine del 5 secoloAc', Annali Ist. Orient.

Napoli 3,79-93.

Coleman R.

'The

1963

dialect geographyof ancient Greece', Trs.Philol. Soc.61,58-126.

Colvin S.C.

1995

Aristophanes:dialect and textual criticism', Mnemosyne48,34-47.

1999

Dialect in Aristophanes: Tlte politics of language in ancient Greek literature,

Oxford.

Dover K.J.

'Notes

1963

on Aristophanes'Acharnians',Maia 15, 6-25. Reprinted in his Greek

and the Greeks,Oxford 1987, 288-306.

'Linguaggio

1976

e carratereAristofaner', Riu. di Cuhura Class.e Med. 18,357-71.

'Language

Tianslated as

and characterin Aristophanes' in his Greekand the

Greeks,Oxford 1987, 237-48.

Hall E.

1989

Inuenting the Barbarian, Oxford.

Hall E. (ed.)

1996

Aeschylus:

Persians,\(/arminster

297

..

Stephen Coluin

Harvey D.

'Lacomica:

1994

Aristophanes and the Spartans',in A. Powell & S. Hodkinson

(eds.) The Shadowof Sparta,London, 35-58.

MacDowell D.M.

'Foreign

1993

birth and Athenian citizenship',in A.H. Sommersteinet al. (eds.)

Tiagedy,Comedyand the Polis,Bari,359-71.

Mattingly H.B.

'The

1997

date and purpose of the pseudo-Xenophon Constitutionof Athens', CQ

47,352-7.

Momigliano A.

1975

AlienWisdom: The limits of Hellenization, Cambridge.

Morenilla-ThlensC.

'Die

1989

Charakterisierungder Ausldnder durch lautliche Ausdrucksmittel in den

Persern des Aischylos sowie den Acharnern und Vi)gelndes Aristophanes',

Indogerm. Forsch.94, 158-7 6.

PageD.L. (ed.)

Alcman: The Partheneion, Oxford.

I95l

SommersteinA.H. (ed.)

198l

1996

Thumb A.

1932

West M.L.

1968

Aristophanes:

Acharniazt'W'arminster.

Aristophanes:Frogs,'Warminster.

and KieckersE.

Handbuch der griechischenDialekte I, Heidelberg.

'Two

passages

ofAristophanes',CR 18, 5-8.

298