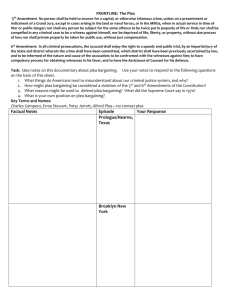

THE ABOLITION OF PLEA BARGAINING: A TEXAS Robert A. Weninger*

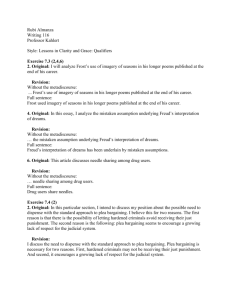

advertisement