1974

advertisement

1974 PHILIP C. JESSUP I NTERNATIONAL LAW

r100T COURT MEt'10RIALS ON BEHALF OF

APPLI CANT AND RESPONDENT, THE STATE OF

INDUSTRIA V. THE STATE OF LATIA

DAVID C. CAYLOR

KENNETH Q. LARSON

, No. 1974-001

IN THE, INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE

AT THE PEACEI='ALACE, THE HAGUE, NETHERLANDS

March Term, 1974

THE

, ..,....

.STATE "OF INDUSTRIA,

.

"

Applicant,

v.

, ,

\THESTATEOF LATIA,

Respondent.

On Submission to the

Interriational Court of Justice

.

, .'"

1· , ' 1

,

••

'

TEAM NO. I

February 22, 1974 ,

. Agents for Industria :

I N 0 E X

Page

Index of Authorities

•

Jurisdiction • • • • •

• • • • • •

Questions Presented • . • ' .

Statement of Facts .

Summary of Argument .

• .

• .

.

• • .

• .

.

.

ii

•

.

.

.

• .

.

.

viii

• •

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

• • .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. ..

.

.

.

.

ix

.•

.

.

ix

.

. ix

Argument and Authorities • • • • • •

I.

THE DEEP OCEAN MINING ACT IS JUSTIFIED UNDER

INTERNATIONAL LAW.

• • • • • • • •

A.

B.

II.

1

1

Freedom of the high seas, both as customarily

practiced and as codified by the 1958 Geneva

Conference on the Law of the Sea, permits Industrian ships to mine the subsoil of the

high seas.

. ....

.. .. . .... .

1

The Deep Ocean Mining Act realistically

meets the needs of the world community by

ensuring adequate mineral suppli e s, preventing partitioning of the high seas , and promoting international cooperation.

•• • • • . • 4

BECAUSE TRACT #1 IS AN AREA OF THE HIGH SEAS

OVER WHICH LATIA HAS NEVER HAD JURISDICTION,

INDUSTRIA ' S MINING OPERATIONS WERE LAWFUL.

A.

Latia's claimed 200-mile fisheries zone

violates international law and cannot

serve as a basis for extending its territorial sea .

B.

C.

7

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Latia's claim to a 200-mile territorial

sea violates the Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone and customary international law.

•••••

.

.

. 7

• • • 9

Because Tract #1 is neither adjacent to

Latia's coast nor expl,oitable, Latia's

claim that its continental shelf extends

to Tract #1 violates the Convention on

the Co~tinental Shelf and customary inter-

national law. · . • • . • . • ••

. . . • . . . 12

ii

Page

D.

III.

Because Latia's claimed 300-mile economic resource zone neither conforms to the

1958 Conventions nor bears any relation

to Latia's capabilities or needs, the

claim violates international law.

..·..

15

• • •

18

·..

18

LATIA'S ACTIONS AGAINST INDUSTRIAN SHIPS

VIOLATED INTERNATIONAL LAW.

• •••••

By ini tiating armed aggression against

Industrian ships · on the high seas, Latia

violated international law.

•••• • •

A.

B.

Latia's unlawful pursuit of Carrier and

use of excessive force against Gatherer

entitl e Industria to compensation for all

damages..

Conclusion •

..

II

..

..

II

..

0

"

lit

..

..

•

Appendix B • •

• •

•

o

I N D E X

..

• •

• • •

• • •

•

. ...

"

..

..

..

..

20

..

• •

•

23

• • •

• •

24

•

• • • • • • •

Appendix A

..

•

• •

25

•

AUT H 0 R I TIE S

F

Page

Treaties

Deep Ocean Mining Act (1973) • • • • • • • • • • • • • ••

DOMA

§

2(b)

•

DOMA

§

2 (c)

• •

DOMA

§

3 •

DOMA

§

4 (c) • • •

DOMA

§

5

DOMA

§ 6 •

DOMA

§

7

.. •

•

• • • • •

.• ..

•

• • • •

• • • • • •

·

•

•

•

• •

• • •

• • •

..

...

..

•

4

.6, 14

• •

..• .• ·.• .....

. . • • • • . . . • • . • 2,

,

• •

.

•

5

7

6

•

• • • •

• • •

1

• • •

·

•

•

5, 6

•

•

.

6

iii

Page

Treaties (Cont.)

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, art. 2(1) (a),

done May 23, 19.69, U.N. Doc. A/CONF. 39/27 • • • • • • • 4

..., ..

Vienna Convention art. 26 •

.

• •

• •

.• .• .

Convention on the High Seas, done April 29 , 1958,

T. LA.S. No. 5200; U. N . T.s:-lf2 • •

•

.

16

..

•

. • · • 2, 3, 16 ,

23 . • . . . . • • . . • •

23 (7) . . .

·....·.

Convention on the High Seas art . 2 • • •

Convention on t he High Seas art .

18

21

'

Convention on the High Seas art.

2

22

Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous

Zone, done April 29, 1958, T.I . A.S . 5639;

516 U.N.T.S. 205 . •

.

.

•.•

.

.....

.

...

•.. 9

Convention on the Territorial Sea art . 24 • • • • • • • • • 16

Convention on the Territorial Sea art . 24(1)

17

Convention on the Territorial Sea art . 24(2)

Convention on the Continental Shelf, done April 28,

1958, T.I.A.S. No. 5578 ; 499 U.N.T.S . 311 •

Convention on the Continental Shelf art. 1 • •

Convention on the Continental Shelf art. 3 •

U.N . CHARTER art. 51 • • •

.......

.

•

....

9

3

• •

12

• • • •

16

.19 , 22

•

Cases

Fisheries Jurisdiction Case , 12 INT'L LEG. MAT.

300 (1973)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

• .

.

• • • • • .

•

8, 9

North Sea Continental Shelf Cases ,

I.C.J . .

.

Fisheries Case,

••

..

. . . . . . .[1969]

.....

.

' 12 , 13 , 16 , 17

[1951] I.C.J. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Corfu Channel Case (Merits),

[1949] I.C.J • • • • • • • • •

9

19

iv

Cases (Cont.)

Page

Claim of the British Ship "I'm Alone" v. United

29 AM. J .

.

Naulila Incident Arbitration 409, 2 U.N.R.I.A.A.

1012 (1928),6 HACKWORTH, INTERNATIONAL LAW

154 (1943) • • . . • • • • • • • • • .

.

" 22

• 22

•

Le Louis [1917] 2 Dods, 210-243 • • • • . • • • •

19

Treatises

J. ANDRASSY, INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE RESOURCES OF

THE SEA (1970)

" .. " " ..

II

"

III

..

"

"

"

•

•

"

•

•

B. BRITTIN & L. WATSON , INTERNATIONAL LAW FOR

SEAGOING OFFICERS (3d ed. 1 9 7 2 ) .

D. BROWN, PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW (1970)

•

•

14

24, 25

1

•

D. BOWETT , SELF-DEFENSE IN INTERNATIONAL LAW (1958)

19

I. BROWNLIE, PRINCIPLES OF PUBLIC I NTERNATIONAL LAW

(2d ed. 1973)

• • • • • • •

• • • . 20

C. COLOMBOS, THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF THE SEA

(6th ed. 1967) • . • • • • • • •

•• • • •

7, 19

Emery, Geological Aspects of Sea-Floor

Sovereignty , in THE LAW OF THE SEA

(L. Alexander ed . 1967)

•••

•

•

14

M. GREEN , INTERNATIONAL LAW (1968)

•

9 , 20

•

D. JOHNSTON & E . GOLD , THE ECONOMIC ZONE IN THE

LAW OF THE SEA : SURVEY, ANALYSIS, AND APPRAISAL OF CURRENT TRENDS, OCCASIONAL

PAPER No. 17 (1973)

•• •

• • • ••

• • •

1 H. LAUTERPACHT, INTERNATIONAL LAW (E. Lauterpacht ed . 1970) . • • • • • •

• ••

J. MERO, THE MINERAL RESOURCES OF

~HE

SEA (1965).

M. MCDOUGAL & W. BURKE , THE PUBLIC ORDER OF THE

OCEANS (1962)

• •• • ••• • • •••• • • •

16

2

5

7, 14

1 NEW DIRECTIONS IN THE LAW OF THE SEA 233 (S. Lay,

R. Churchill, & M. Nordquist ed. 1973) • • • • • • 11

v

Page

Treatises (Cant.)

S. ODA, INTERNATIONAL CONTROL OF SEA RESOURCES

(1963) • . . • • • . • • • •

• • • • • 3, 15

....

S. ODA, THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF OCEAN DEVELOPMENT (1972) • • • • • • • • • • • • •

....... 7

2 L. OPPENHEIM, INTERNATIONAL LAW (7th ed.

H. Lauterpacht 1952) • • • • • • • • •

. . . . . . 22

POULANTZAS, THE RIGHT OF HOT PURSUIT IN INTERNATIONAL LAW (1969) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 21, 22

1 G. SCHWARTZENBERGER, INTERNATIONAL LAW (3d ed .

1957) . . . . . . . . . . . • . . . . . . .

2 G. SCHWARTZENBERGER, INTERNATIONAL LAW (196B)

...

•

1

• 19 , 21

Z . SLOUKA, INTERNATIONAL CUSTOM AND THE CONTINENTAL SHELF (1966) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 14

J. STARKE, AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNATIONAL LAW

(7th ed. 1972)

• • • • • • • •

R. SWIFT, INrERNATIONAL LAW (1969)

•

• •

11

4 M. WHITEMAN, DIGEST OF INTERNATIONAL LAW (1965) • • •

5

22

•

M. WHITEMAN, DIGEST OF INTERNATIONAL LAW (1965)

B, 11

• ••

19

Periodicals

Bowett, Collective Self-Defense Under the Charter of

the United Nations, 32 BRIT. Y. B. INT'L L.

1955-56, at 130 (1957) • • • • • • • "• • • •

Friedmann , Selden Redivivus--Toward a Partition

of the Seas? , 65 AM. J . INT'L L . 757 (1971)'.

. . . 19

....

Goldie , International Law of the Sea: A Review of

States' Offshore Claims and Com etences , 24

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REV .

Fe • 1

•• •

• • • . 10

4

Knight, The Deep Seabed Hard Miner al Resources

Act--A Neyative View, 10 SAN DIEGO L . REV.

446 (1973

. • • • • • •

...............

10

vi

Page

Periodicals (Cont.)

Sea Minin , 7 SAN

5, 6, 13, 14

Nelson, The Patrimonial Sea, 22 INT'L L. &

COMPo L. Q. 668 (1973).

• ••• •

.. .. .. .. . . .

10

Pardo, An International Regime for the Deep

Seabed: Develo in Law or Develo in Anarch?,

TEX . INT L L. F.

.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. • • • 13, 17

Phleger, Recent Develoements Affecting the Re,ime

of the Hilh Seas, ~n DEP'T STATE BULL. 93

(June 6,

955) . ... ...... . .... . . .... .. . .

.. . .. ..

11

428 (1969) ...... . ...... . . . .. . .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. .

lB

Note, Seizure of United States Fishing Vessels-The Status of the Wet· war, 6 SAN DIEGO L. REV.

Misc e llaneous

American Tuna Boat Association, DATA ON SEIZURES

OF U.S. TUNA BOAT CLIPPERS DURING PERIOD JANUARY

1961-JUNE, 1969, Table 1 (1969) • • • • • • • • • • • • • B

The Bulgaria--Czechoslovokia--Hungary--U.S.S.R.

Declaration of 1972, 12 INT'L LEG. MAT. 215

(1973)

......

..

..

..

..

....................

. .. . . ..

..

The Colombia--Mexico--Venezuela Declaration of 1973,

12 INT'L LEG. MAT. 570 (1973) • • • • • • • • •

11

• • • 11

COMM'N TO STUDY THE ORG. OF PEACE, Nineteenth Rep.,

THE UNITED NATIONS AND THE BED OF THE SEA 16

(1970) ..........

..

..

..

........

....

..

.. -.

.. ...

..

7

COMM'N TO STUDY THE ORG. OF PEACE, Twenty-First Rep.,

THE UNITED NATIONS AND THE BED OF THE SEA (II)

17

(1970)

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

4, 15

..

The Comm. on Deep Sea Mineral Resources of the Am.

Branch of the Int'l L. Ass'n, Second Interim Report on Deep Sea Mineral Resources pt. VII, in

THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF THE OCEAN DEVELOPMENT

(5.. Oda ed..

1972)

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

...

3

vii

Miscellaneous (Cont . )

Page

Henkin, The Continental Shelf , in FOURTH ANNUAL

CONFERENCE OF THE LAW OF THE SEA INSTITUTE,

THE LAW OF THE SEA: NATIONAL POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS 171 (L. Alexander ed. 1969) • •

·..

10

G.A. Res. 2574, 24 U.N. GAOR. U.N. Doc. A/7834

(1969) . . . . . .. • . . • • . . . . . . . • • • •

16

Inter-American Juridical Comm., Opinion on the

Breadth of the Territorial Sea 1969 O.A.S'./OD

O. E.A./Ser.l/VI.2 (English) CIJ-80, at 33

& n.49 • • • .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

17

·..

Int'l L. Comm'n, Report, 11 U.N . GAOR, Supp. 9 ,

at 24, U.N . Doc . A/3l59 (1956) • • • • • • •

2, 9, 16

Int'l L. Comm'n, Report, 23 U. N. GAOR, at 9, 10,

U.N. Doc. A/AC. 135/19 Add. 1 (1968) • • • • • • • • 1

Report of the 358th Meeting, 1 Y. B. INT'L L .

COMM'N 136 (1956) • • • • • • • , • • • • ..

Santo Domingo Declaration, 11 INT'L LEG. MAT,.

892 (1972) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

.. ..

.

..

12

..·..

11

23 U.N. GAOR, Ad Hoc Comm. To Study t he Peaceful

Uses of the Sea-bed and the Ocean Floo'r Beyond

the Limits of National Jurisd. , A/AC.135/R.l

(1968)

..

..

....

..

........

..

..

....

....

..

..

..

..

..

4, 7

23 U.N. GAOR, Ad Hoc Comm. To Study the Peaceful

Uses of the Sea-bed and the Ocean Floor Beyond ,

the Limits of National Jurisd. , A/AC.135/R.5

(1968)

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

5, 6

24 U.N. GAOR, Report of Comm. on the Peaceful Uses

of the Sea-bed and the Ocean Floor Beyond the

Limits of National Jurisd., Supp. 22 , at 108,

1 09. U. N• Doc . A/7 622 (1969) • • • • • 3, 5 , 6 , 7 , 13

viii

BEFORE THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE

. MARCH TERM

1974

CASE NO. 1974-001

THE STATE OF INDUSTRIA,

Applicant

v.

THE STATE OF LATIA,

Respondent

MEMORIAL FOR THE APPLICANT

J URI S D I C T ION

The parties have agreed to submit this dispute to the

International Court of Justice for its determination.

ix

oU

I.

II.

III.

EST ION S

PRE SEN TED

WHETHER THE DEEP OCEAN MINING ACT IS JUSTIFIED UNDER

INTERNATIONAL LAW?

WHETHER LATIA HAS JURISDICTION OVER TRACT 11?

WHETHER LATIA'S ACTIONS AGAINST INDUSTRIAN SHIPS

VIOLATED INTERNATIONAL LAW?

o

STATEMENT

F

F ACT S

The parties have ' stipulated the facts before the Court.

SUMMARY

o

F

A R GUM E N T

The Deep Ocean Mining Act is justified under international

law.

Under the principle of freedom of the high seas, Indus-

trian ships

~ave

the right to mine the subsoil of the high seas.

Furthermore, the Deep Ocean Mining Act complies with the 1958

Geneva Conventions by protecting the freedom of the high seas

and ensuring the orderly development of ocean resources.

Because Tract #1 is an area of the high seas, and Latia

has never had jurisdiction over it, Industria's mining operations on Tract #1 were lawful.

By initiating armed aggression against Industrian ships

on the high seas, Latia violated international law.

Latia's

unlawful pursuit of Carrier, and its use of excessive force

against Gatherer, entitle Industri'a to compensation for ' all

damages.

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES

I.

THE DEEP OCEAN MINING ACT IS JUSTIFIED UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW.

A.

Freedom of the high seas, both as customarily

practiced and as codified by the 1958 Geneva Converence on the Law of the Sea, ~ermits Industrian ships

to mine the subsoil of the h~gh seas.

The ri hts authorized b the Dee

tent w~t ~nternat~ona law.

Ocean Minin

Act are consis-

The high seas are those parts of the oceans which lie seaward of any nation's territorial sea.

INTERNATIONAL LAW 338 (3d ed. 1957).

1 G. SCHWARTZENBERGER,

The principle of the free-

dom of the high seas as recognized by customary international

law applies to all the waters of the open sea.

INTERNATIONAL LAW 102 (1970).

D. BROWN, PUBLIC

One corollary of this principle

is that all states may exploit the minerals and organic

resources of the high seas and its subsoil.

Id. at 103.

The International Law Commission Special Rapporteur on the

Law of the Sea has noted that the subsoil of the high seas is

capable of at least temporary occupation for scientific and

economic activities as long as there is no unreasonable interference with navigation.

Int'l L. Comm'n, Report, 23 U.N.

GAOR, at 9, 10, U.N. Doc. A/AC. 135/19 Add. 1 (1968). Accord,

ingly, the Deep Ocean Mining Act [DOMA) permits only temporary occupation of licensed areas of the high seas, for the

limited purpose of extracting minerals, and prohibits

2

unreasonable interference with any customary use of the ocean.

DOHA § 4(c).

DOHA therefore, is consistent with customary

international law.

DOHA complies with the 1958 Geneva Conventions by protecting

the freedom of the high seas and ensuring the orderly development of ocean resources.

The 1958 Geneva Conventions produced the most successful

codification of the customary law of the sea .

PACHT, I NTERNATIONAL LAW 98

1 H. LAUTER-

(E . Lauter pacht ed . 1970).

Freedom of the high seas is defined in Article 2 of the

Convention on the High Seas.

The Convention observed that

freedom of the high seas i s comprised of not only the freedoms of navigation, fishing, cable-laying and overflight, but

also of other freedoms which are recognized by the general

principles of international law.

Convention on the High

Seas , done April 29 , 1 958 , T.I.A . S. No . 5200; 450 U. N. T.S.

82 [ hereinafter cited as CHSJ .

The International Law Com-

mission explained that these other freedoms include the freedom to mine mineral resources .

Int ' l L. Comm'n , Report, 11

U.N. GAOR, Supp. 9 , at 24, U.N. Doc . A/3l59 (1956)

after cited as 11 1. L.C.J.

[herein-

DOHA violates none of the free-

doms enumerated by the Convention; on the contrary , DOHA

makes express provision for protecting the traditional freedoms of the seas by authorizing it,!> secretary to prevent any

unreasonable interference with ocean usage.

DOHA 5 4(c).

DOHA thereby gives its member-states the administrative control deemed neces s ary by t he U.N. Permanent Sea-bed Committee

3

to ensure the protection of these freedoms.

24 U.N. GAOR,

Report of the Comm. on the Peaceful Uses of the Sea-bed and

the Ocean Floor Beyond the Limits of National Jurisd., Supp.

22, at 108, 109, U.N. Doc. A/7622 (1969)

[hereinafter cited

as Sea-bed Comm.J.

The right of DOMA licensees to exploit submarine resources requires no

~ew

doctrinal justification:

herent in freedom of the high seas.

CONTROL OF SEA RESOURCES 151 (1963).

it is in-

S. ODA, INTERNATIONAL

Indeed, as long as min-

ing operations are conducted with reasonable regard for the

interests of other states, as Ocean Mining Company's operations

are, the operations are permitted and protected by international law.

The Comm. on Deep Sea Mineral Resources of the

Am. Branch of the Int'l L. Ass'n, Second Interim Report on

Deep Sea Mineral Resources pt. VII, in THE INTERNATIONAL LAW

OF THE OCEAN DEVELOPMENT (S. Oda ed. 1972).

Since DOMA

operations are specifically limited to extracting hard minerals from the subsoil of the high seas, no DOMA state purports to subject any part of the high seas to its sovereignty.

Therefore, DOMA complies with the CHS by respecting the freedom of the seas.

CHS art. 2.

The Convention on the Continental Shelf [CCSJ, to ensure

the orderly development of the ocean's resources, limited

mining by non-coastal nations to the subsoil of the high seas.

Convention on the Continental Shelf, done April 28, 1958,

T.I.A.S. No. 5578; 499 U.N.T.S. 311 [hereinafter cited as ccsJ.

DOMA recognizes and implements this aspiration by incorporating

4

the Convention's definition of continental shelf.

2(b).

DOMA S

This explicit reference to the Convention on the Con-

tinental Shelf is convincing evidence that the framers of

DOMA intended DOMA to reflect the spirit of all the Conventions.

B.

The Deep Ocean Mining Act realistically meets the

needs of the world community by ensuring adequate

mineral supplies, preventing partitioning of the

high seas, and promoting international cooperation.

Multilateral treaties are particularly desirable for meeting the needs of the world community.

Friedmann, Selden Re-

divivus--Towards a Partition of the Seas?, 65 AM. J. INT'L

L. 757, 770 (1971) .

DOMA is a multilateral treaty as defined

by the Vienna Convention.

Treaties,

39/27.

art~

Vienna Convention on the Law of

2(1) (a), done May 23, 1969, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.

Such treaties are an efficient and equitable method

for ensuring the orderly and progressive exploitation of the

resources of the high seas.

23 U.N. GAOR, Ad Hoc Comm. to

Study the Peaceful Uses of the Sea-bed and the Ocean Floor

Beyond the Limits of National Jurisd., A/AC.135/R.l, at lB

(196B)

[hereinafter cited as Ad Hoc Comm.l.

Multilateral

treaties impose enforceable self-restraints on their participants and avoid the unlimited and disruptive claims resulting

from unreasonable unilateral actions such as Latia's.

See

COMM'N TO STUDY THE ORG. OF PEACE, -'Twenty-First Rep., THE

UNITED NATIONS AND THE BED OF THE SEA (II) 17 (1970)

[here-

inafter cited as U.N. & BED OF THE SEAl.

DOMA requires its

members to adhere to specific regulations

~hich

prevent

5

unlimited prescription of the high seas.

DOMA § 3.

Thus,

DOMA prevents a massive race to partition the seas through

unilateral action.

Manganese nodules contain at least fifteen metals essential to the world's continuing industrial and technological

development.

Mero, A Legal Regime for Deep Sea Mining, 7 SAN

DIEGO L. REV. 4BB, 496 (1970)

DIEGO].

[hereinafter cited as 7 SAN

Although these minerals are being rapidly depleted

on land, the oceans contain vast reserves sufficient to meet

the world's needs.

27B (1965).

J. MERO, THE MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE SEA

Most developing coastal states with extended

jurisdiction cannot effectively exploit the resources within

these areas because they lack sufficient technology.

The re-

sult will be a critical shortage of vitally needed resources.

Ad Hoc Comm. 11.

DOMA prevents the void resulting from lack

of adequate production by encouraging mutual assistance and

cooperation among participating states.

DOMA § 6.

Securing adequate supplies and systematic production of

minerals from ocean resources will stabilize world markets by

averting fluctuations in market prices caused by shortages.

Sea-bed Comm. 109.

The cooperation engendered by DOMA dis-

courages price manipulation by single-nation monopolies.

Additionally, the security which DOMA provides its licensees

will attract · the investment

capit~l

exploitation of ocean resources.

needed to realize effective

6

DOMA's ~rovision for recognition of its licensees by any

future ~nternational regime is necessary for the realization of orderly ocean development.

Section 7 of DOMA protects the investments of licensees

under any forthcoming international regime.

This provision

is reasonable and necessary for DOMA to be a viable solution

to the problems involved in ocean mining.

DOMA § 7.

The

high costs involved in exploring and developing ocean mineral

sites would render non-recognition by an international regime

an inequity to licensees and would greatly discourage investment, exploration, and exploitation.

Because experts suggest licensing tracts of 1,000 to 5,000

square miles, the 100-square-mile maximum tract size allowed

by DOMA would be reasonable under any future regime.

§

2 (c); 7 SAN, DIEGO 488, 500.

DOMA

DOMA' s trust fund contr ibutes

an equitable amount to developing states; therefore, permitting

the continuation of mining operations under DOMA licenses

would not impair the functioning of the regime.

Ad Hoc Comm., U.N. Doc.

A/AC.13~/R.5,

DOMA § 5, 6;

at 11.

The restrictions placed on licensees by DOMA are extremely

stringent and would probably exceed those of any future international regime.

Sea-bed Comm. 153.

Moreover, DOMA's licens-

ing period of twenty years is brief, so that even if it

proved incompatible with an international regime the remaining licensing period would be relatively short.

The licensing provisions of DOMA are consistent with

those of the U.N. Seabed Committee's Legal Sub-committee.

Both licensing programs employ a "double C?oncession system"

7

in which the state acts as the administrator of the mining

operations.

Sea-bed Comm. 108 & n.26.

As administrators of

these operations, DOMA nations can ensure effective exploitation while protecting the other uses of the oceans.

DOMA

§

4(0), ~ Ad Hoc Comm., U.N. Doc. A/AC.l35/R.l, at 16.

Moreover, a prime requisite of the proposed regime will

be to grant companies the security of tenure necessary for inducing investment of the large sums essential to ocean development.

COMM'N TO STUDY THE ORG. OF PEACE, Nineteenth Report,

THE UNITED NATIONS AND THE BED OF THE SEA 16 (1969).

It is

reasonable for DOMA to give its licensees the same protection

that an international regime will give its licensees.

II.

BECAUSE TRACT #1 IS AN AREA OF THE HIGH SEAS OVER WHICH

LATIA HAS NEVER HAD JURISDICTION, INDUSTRIA'S MINING

OPERATIONS WERE LAWFUL.

A.

Latia's claimed 200-mile fisheries zone violates

international law and cannot serve as a basis for

extending its territorial sea.

Latia ' s claim to fisheries jurisdiction does not conform

to the customary practice of nations.

The 1958 Geneva Con-

ference did not recognize exclusive fisheries zones such as

Latia has claimed.

M. MCDOUGAL & ·W. BURKE, THE PUBLIC ORDER

OF THE OCEANS 539 (1962)

BURKE]

I

[hereinafter cited as MCDOUGAL &

C. COLOMBOS, THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF THE SEA

(6th ed. 1967).

§

27a

Over two-thirds · (fifty-seven) of the world's

developing coastal states do not claim exclusive fisheries

jurisdiction beyond twelve miles.

S. ODA, THE INTERNATIONAL

LAW OF OCEAN DEVELOPMENT 372 (1972).

8

Regular protests of fisheries zones such as Latia's

demonstrate that such zones are inconsistent with international

law.

4 M. WHITEMAN, DIGEST OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 1102 (1965).

General lack of recognition of claims to extended fisheries

jurisdiction has been fur.ther demonstrated by continued fishing of the declared zones by foreign nationals.

See American

Tuna Boat Association, DATA ON SEIZURES OF U.S. TUNA BOAT

CLIPPERS DURING PERIOD JANUARY 1961-JUNE 1969, Table 1 (1969) .

In fact, periodically, Latia has had to exclude foreign fishing ships from its own declared zone.

This continued non-

recognition of Latia's claimed fisheries jurisdiction, viewed

in conjunction with widespread protest and infringement of

similarly claimed zones, demonstrates that Latia's claim has

no basis in international law .

In the Fi~heries Jurisdiction Case of 1973, Judge Sir

Gerald Fitzmaurice recognized that there is no generally accepted method of validly asserting exclusive fisheries jurisdiction unilaterally, except as part of a valid claim to

territorial waters .

Fisheries Jurisdiction Case, 12 INT'L

LEG. MAT . 300 , 312 (1973).

When Latia cla'imed its fisheries

zone, it had no territorial sea upon which to base this claim.

Thus, Latia's claim to a 200-mile fisheries zone is invalid.

A void exercise of jurisdiction can never be the basis for

further assertions of jurisdiction,.

Therefore, Latia cannot

base its claim to a 200-mile territorial sea upon an invalid

claim to a 200-mile fisheries zone.

9

B.

Latia's claim to a 200-mile territorial s e a violates

the Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous

Zone and customary international law .

This Court has declared arbitrary, unilateral extensions

of territorial seas to be unlawful.

I.C.J. 132.

Fisheries Case,

[1951]

Extensions of two hundred miles are arbitrary

under any circumstances.

The vast majority of states agree

that claims to more than twelve miles violate international

law.

M. GREEN, INTERNATIONAL LAW 205 (1973) .

In preparing

its draft of the 1958 Territorial Sea Convention, the International Law Commission expressly sta t ed that extensions

beyond twelve miles derogate from freedom of the seas and are

not permitted under international law.

11 I.L.C . 13.

Arti-

cle 24(2) of the Convention on the Territorial Sea and the

Contiguous Zone states that a nation claiming a twelve-mile

territorial sea is entitled to no . contiguous zone .

Conven-

tion on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, art . 24(2),

done April 29 , 1958 , T.I.A.S. 5639; 516 U.N.T.S. 205 [hereinafter cited as CTSCZ]; Fisheries Jurisdiction Case, 12 INT ' L

LEG. MAT. 310, n.l (1973).

The implication of this provision

is that no state may claim a territorial sea beyond twelve

miles .

Fisheries Jurisdiction Ca se, 12 INT'L LEG. MAT. 310 ,

n.l (1973).

Twelve miles, therefore, is the prescribed outer

limit of the territorial sea , and ,,any extension beyond that

distance is contrary to the CTSCZ.

International law prohibits claims of limited jurisdiction,

such as Latia's claim to a 200-mile fisheries zone, from

10

ripening into claims of total national sovereignty.

Knight,

The Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act--A Negative View,

10 SAN DIEGO L. REV. 446, 456 (1973).

This device, sometimes

called creeping jurisdiction, would allow Latia to do indirectly that which it cannot do directly .

Henkin , The Con-

tinental Shelf, in FOURTH ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE LAW OF THE

SEA INSTITUTE, THE LAW OF THE SEA:

NATIONAL POLICY RECOMMENDA-

TIONS 171, 175-76 (L. Alexander ed. 1969).

Creeping juris-

diction jeopardizes local, regi9nal, and international interests in the freedom of the seas.

the Sea:

Goldie, International Law of

A Review of States ' Offshore Claims and Competences,

24 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REV. 43, 52 (Feb. 1972) .

The reality of the danger is manifest in Latia ' s past and

present actions.

Latia's 200-mile fisheries zone, although

excessive, was at least limited in its allegation of sovereignty.

In 1966, however, Latia shed any pretense of preserv-

ing the limitation, and even today it purports to exercise

full sovereignty over the entire 200-mile zone .

Now another

new claim , unfounded and vaguely defined, stretches across an

unprecedented three hundred miles of high sea.

The survival

of the traditional freedoms of the sea in this extensive area

is seriously threatened.

Latia's past claims reinforce the

probability that it is attempting to lay the foundation for a

future claim to a 300-mile territorial sea.

See Nelson, The

Patrimonial Sea, 22 INT'L & COMP o L. Q. 668, 683 (1973).

The

prohibition against creeping jurisdiction protects the high

11

seas from such unilateral nationalization of seabed resources.

R. SWIFT, INTERNATIONAL LAW 264 (1969).

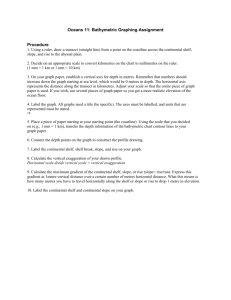

The effect of all

nations' claiming territorial seas of two hundred miles would

be to reduce vast areas of the high seas to national sovereignty.

[See Appendices.)

There are additional reasons for this Court to reject

Latia's claim to a 200-mile territorial sea.

Numerous multi-

lateral declarations have affirmed the principle that no state

may validly extend the limits of its territorial sea beyond

twelve miles.

~.,

Santo Domingo Declaration, 11 INT'L LEG.

MAT. 892 (1972); The Columbia--Mexico--Venezuela Declaration

of 1973, 12 INT'L LEG. MAT. 570 (1973); The Bulgaria-Czecholovokia--Hungary--U.S.S.R. Declaration of 1972, 12

INT'L LEG. MAT. 215 (1973).

Attempted extensions of terri-

torial seas beyond twelve miles have been vigorously protested .

Phleger, Recent Developments Affecting the Regime of the High

Seas, in DEP ' T STATE BULL. 937 (June 6, 1955).

Because of

such protests, most states which formerly claimed territorial

seas of two hundred miles have recanted, now declaring that

they are exercising only limited jurisdiction .

See 1 NEW

DIRECTIONS IN THE LAW OF THE SEA 233 (S. Lay . R. Churchill,

& M. Nordquist ed. 1973); 4 M.

~iITEMAN,

DIGEST OF INTER-

NATIONAL LAW 69 (1965).

Even Latia has manifested insecurity in its position.

On one hand it asserts sovereignty over Tract #1, while on

the other hand it admits an obligation to the world community

12

which is inconsistent with its claim of total sovereignty.

If Latia had exclusive sovereignty over Tract #1, it had no

obligation to share the income from this area.

By setting

aside ten per cent of the profits from Tract #1, Latia

tacitly admits that the tract is on the high seas.

Since Tract #1 is outside Latia's jurisdiction, this

Court should uphold Industria's right to mine that tract.

C.

Because Tract #1 is neither adjacent to Latia's

coast nor exploitable, Latia's claim that its continental shelf extends to Tract #1 violates the

Convention on the Continental Shelf and customary

international law.

The CCS stated that beyond the depth of two hundred

meters, the limits of the continental shelf are to be determined by applying the criteria of adjacency and exploitability

conjunctively.

CCS art. 1.

Tract #1 is neither adjacent to

Latia's coast nor is it exploitable.

The term adjacency was originally proposed by Frederico

Garcia Amador, chairman of the International Law Commission,

who stated that adjacency would not encompass extensions

beyond 25 miles.

Report of the 358th Meeting, 1 Y. B. INT'L

L. COMM'N 136 (1956).

This Court has recently taken the position that "by no

stretch of the imagination can a point • • • say a hundred

miles, or even much less, from a given coast, be regarded as

'adjacent' to it • • • • "

[19691 I.C.J. 30.

North Sea Continental Shelf Cases.

13

Tract #1 is no more exploitable than it is adjacent.

Under any application of exploitability, Latia's claim to

sovereignty over Tract #1 is invalid.

This Court, as well as

other authorities, has recognized that the 1958 Convention's

definition of exploitability was not intended to authorize

unlimited extensions of jurisdiction.

Id. at 103; Sea-bed

Comm . 83; 7 SAN DIEGO 488, 494.

Latia has attempted to use the exploitability criterion

· to claim jurisdiction over an area of the seabed 120 miles

off its coast.

To base the exploitability criterion on either

Industria's present or Latia's future exploitative capabilities,

would allow any state to extend its sovereignty to mid-ocean.

Because Latia's technology is not sufficiently advanced to

utilize the resources of Tract #1, Latia has no reasonable

basis for asserting jurisdiction over the area.

Latia ' s at-

tempted extension of its continental shelf to Tract #1 is,

therefore, just as unreasonable as an extension to mid-ocean:

neither bears any relation to Latia's capabilities ' or needs.

Permitting a coastal state to denominate the deep seabed

as a continental shelf on the basis of its future capability

or other nations' present capability to utilize shelf resources would be disastrous .

When nations realized that sover-

eignty could be obtained by simple proclamation there would be

a massive rush to partition the high seas.

national Regime for the Deep Seabed:

Pardo, An

Inter-

Developing Law or De-

veloping Anarchy?, 5 TEX . INT'L L. F. 204, 207

(1970).

14

Assuming, arguendo, that the test to be applied in determining exploitability is the technical ability of other

states to exploit, Latia still cannot claim Tract #1.

The

ability to extract small quantities of minerals does not

prove that bulk recovery is possible.

J. ANDRASSY, INTER-

NATIONAL LAW AND THE RESOURCES OF THE SEA 78

(1970).

The

measure of exploitative capability includes not only technical potential but also such practical limiting factors as

the economics of the enterprise.

leas t

~ ne

MCDOUGAL & BURKE 690.

At

thousand square miles of seabed will be necessary

to render the recovery of manganese nodules profitable.

DIEGO 500.

7 SAN

By this standard the maximum tract size granted

under DOMA is too small to yield a profit • . DOMA § 2(c).

Additionally, the cost of metals extracted from manganese

.nodules will exceed that of land based sources for years to

come.

Emery, Geological Aspects of Sea-Floor Sovereignty, in

THE LAW OF THE SEA 154 (L. Alexander ed. 1967).

Exploitation

is only proven possible when shown to be economically feasible.

z.

SLOUKA, INTERNATIONAL CUSTOM AND THE CONTINENTAL SHELF 104

(1966).

Since extraction of nodules from - Tract #1 has not

been proven to be profitable, Latia cannot successfully maintain that Tract #1 has been proven exploitable.

If one ship-

load of unrefined ore were deemed to be proof of exploitability,

other states would attempt to follow Latia's lead.

Subsequent

extensions by Latia and other states would create vast areas

which no one could develop and states with little or no coast

15

would be totally excluded from deep ocean development.

U.N.

& BED OF THE SEA 17.

Prior to its seizure of Gatherer, Latia had no technological ability to exploit manganese nodules.

The technical

knowledge which Latia now possesses was seized illegally from

Industria, and therefore Latia has no valid claim to technological ability.

Assuming, arguendo, that this Court finds that Latia now

possesses the technological ability to mine Tract #1, Latia

still could not employ the exploitability criterion as a

basis for extending its sovereignty.

Latia cannot now extend

sovereignty over Tract #1 because subsequent technological

discoveries cannot be used as the basis for validating prior

claims.

Moreover, technological ability to exploit requires

a showing of the capacity to ensure an effective long-range

development of the claimed area.

Because neither Ocean Mining

Company nor Latia has proven Tract #1 to be exploitable,

. Latia's assertion has no basis in international law.

There-

fore, this Court should find that Latia has no jurisdiction

over Tract # 1.

D.

Because Latia's claimed 300-mile economic resource

zone neither conforms to the 1958 Conventions nor

bears an relation to Latia's ca abilities or needs

the c a1m V10 ates 1nternat1onal law.

International law does not recognize the economic resource

zone concept employed by Latia.

OF SEA RESOURCES 20 (1963).

S. ODA , INTERNATIONAL CONTROL

As a party to the 1958

16

Conventions, Latia is bound to recognize areas beyond its

twelve-mile territorial sea as being high seas not subject

to the jurisdiction of any state.

CHS art. 2; CCS art. 3.

Latia's claim to a three ' hundred-mile zone violates its

treaty obligations and thus violates international law.

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, art. 26, done May

23, 1969, U.N. Doc. A/CONF,' 39/27.

The purpose of the Geneva Conventions is to promote the

orderly development of the oceans.

North Sea Continental Shelf Cases,

See 11 I.L.C. 2-4;

(1 969) I.C.J. 92.

Uni-

lateral extensions based on eonomic resource zones undermine

this purpose.

Actions such as Latia's would subject the en-

tire ocean floor to similar unjustified claims, thus violating

principles espoused by the international community.

G.A. Res.

2574, 24 U. N. GAOR, U.N. Doc. A/7834 (1969) .

There is no essential difference between an economic resource zone and a contiguous zone.

Under both the economic

resource zone concept and the contiguous zone concept, coastal

states would exercise limited jurisdiction for specific purposes over areas lying adjacent to their coasts.

D. JOHNSTON

& E. GOLD, THE ECONOMIC ZONE IN THE LAW OF THE SEA:

SURVEY,

ANALYSIS AND APPRAISAL OF CURRENT TRENDS, OCCASIONAL PAPER No.

17, at 1

(1973); CTSCZ art. 24.

The economic resource zone concept alluded to by the InterAmerican Juridical Committee would permit a coastal state to

exercise limited jurisdiction over adjacent coastal waters

17

for the regulation of fiscal matters.

Inter-American Juridi-

cal Comm., Opinion on the Breadth of the Territorial Sea [19661

O.A.S./OD O.E.A./Ser.l/VI.2 (English) CIJ-80, at 33 & n.49.

This limited authority is identical to that which the CTSCZ

grants the coastal state.

CTSCZ art. 24(1).

Latia's econo-

' mic resource zone, therefore, is nothing more than a contiguous zone.

Since the CTSCZ expressly prohibits the establish-

ment of such a zone beyond twelve miles, Latia's claim to a

300-mile economic resource zone i s unlawful.

This Court has recognized that extensions of national

jurisdiction over the ocean must conform to the 1958 Conventions and be reasonabl e in relation to the coastal state ' s

particular needs.

I.C.J. 50 , 51 .

North Sea Continental Shelf Cases,

[19691

Latia ' s actions do not guarantee the freedom

of scientific research.

Mr . Arvid Pardo , Malta's ambassador

to the United Nations , pointed out that unilateral acts such

as Latia's will probably interfere with the freedom of scientific resea rch and al l other traditional freedoms of the high

seas .

Pardo , An International Regime for the Seabed :

Devel-

oping Law or Developing Anarchy? , 5 TEX . INT ' L L. F. 204, 206

(1970).

Latia ' s unlawful attempt to extend its jurisdiction

has prevented Industria from exerc i sing its rights to the

freedoms of scientific research , navigation , and exploitation.

Latia's ~laims neither conform to the 1958 Conventions,

nor bear any relation to Latia ' s capabilities or needs .

Thus,

Latia's actions are contrary to international law, and should

18

be so declared by this court.

III.

LATIA'S ACTIONS AGAINST INDUSTRIAN SHIPS VIOLATED

INTERNATIONAL LAW.

Latia ' s seizure of Industrian ships and its subsequent

actions violated international law .

lawful for two reasons:

These actions were un-

first, Latia initiated armed aggres-

sion against Industrian ships; and second, Latia used excessive force following . an unlawful pursuit on the high seas.

A.

By initiating armed aqqression against Industrian

ships on the high seas, Latia violated international

law.

No state may lawfully claim sovereignty over the high seas.

CHS art. 2.

Latia's unwarranted extension of its territorial

sea is an indefensible attempt to usurp the freedom of all nations to use the high seas .

Because Latia gave notice to the world that it would use

force to further its unfounded claims , Industria was entitled

to give its citizens a modicum of protection by arming

Gatherer .

Note , Se i zure of United States -Fishing Vessels--

The Status of the Wet War , 6 SAN DIEGO L. REV . 428, 439-40

(1 969).

That these token arms were- not intended for aggres-

sive use was demonstrated by Gatherer's refusal to retaliate

against Latia's unprovoked attack . ,

Gatherer was engaged in lawful mining activities on the

high seas when Interceptor appeared and demanded that Gatherer

depart .

Gatherer had the right to give notice by firing a

19

return warning shot that it would not willingly give up its

rights on the high seas unless forced to do so.

This Court

has recognized that states are not bound to refrain from

exercising lawful rights merely because they may be challenged

or even resisted by coastal states.

Corfu Channel Case

(Merits), [19491 I.C.J. 29.

Latia's use of force was excessive and unjustified on

any grounds .

A universally accepted doctrine of international

law establishes that " a merchant ship flying the flag of a

recognized state is immune from interference on the high seas

by the ships of any nation other than its own.

Le Louis [19171

2 Dods, 210-243; COLOMBOS, THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF THE SEA

S 333 (6th ed. 1967).

Nevertheless, Interceptor attacked

Gatherer without provocation, damaged the ship and injured

some of its crew.

Certainly the doctrine of self-defense cannot be invoked by Latia to defend its actions on the high seas.

SCHWARTZENBERGER,INTERNATIONAL LAW 32 (1968).

2 G.

Self-defense

cannot be exercised against one who is acting lawfully.

BOWETT, SELF-DEFENSE IN INTERNATIONAL LAW" 256 (1958).

defense is a response to the act of aggression.

MAN, DIGEST OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 979 (1965).

D.

Self-

5 M. WHITE-

For the doc-

trine to be invoked, the accused aggressor must be the first

to act.

In the absence of such an act there can be no self-

defense.

Because Industria committed no act of aggression

Latia cannot validly assert a right to self-defense.

U.N.

CHARTER art. 51; Bowett, Collective Self-Defense Under the

20

United Nations, 32 BRIT. Y. B. INT'L L. 1955-56, at 130, 148

(1957).

Latia's use of force, therefore, was unlawful.

Furthermore, self-help cannot be used to resolve disputes

over territory:

[T)he territorial privilege is subject to curtailme nt in cases of dispute:

the. claim to the privilege cannot be supported by self-help which would

render the right , ~ post facto, extraterritorial,

and serious breaches of the peace are not a justifiable means of upholding exceptional rights .

I.

BROWNLIE, PRINCIPLES OF PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW

366 (2d ed. 1973).

Territorial privileges over Tract #1 were in dispute.

Latia

wrongfully claimed full sovereignty, while Industria engaged

in limited activities universally permitted on the high seas.

Latia resorted to armed aggression against a merchant ship

and a mining rig, thereby violating international law.

B.

Latia's unlawful pursuit of Carrier and use of

excessive force against Gatherer entitle Industria

to compensation for all damages.

Latia's seizure and adjudication of Gatherer and Carrier's

cargo violate international law .

Where recognized responsi-

bilities under international law are violated, municipal law

is irrelevant.

M. GREEN , INTERNATIONAL LAW 244-45 (1973).

Even if Latia's actions are in compliance with its municipal

law, reliance upon municipal legislation cannot validate

actions otherwise invalid under international law.

Under t he CHS hot pursuit may be commenced only within

the territorial sea and then only after the pursued ship is

21

notified by visual or auditory signals.

CHSart. 23.

The

only notice given Carrier occurred beyond Latia's claimed

territorial sea, making Latia's pursuit and seizure direct

violations of international law.

Because no notice was given

Carrier, as required by this convention, hot pursuit could

not have been commenced lawfully.

Furthermore, although Industria's mining operations had

been in progress for several days, Latia waited until the

first load of nodules had been recovered before commencing

pursuit of Carrier.

Even if Latia at one time had the right

to pursue, its failure to take timely action constituted an

abuse of rights which is a breach of international law.

The

substantial lapse of time between commencement of mining

operations

a~d

the pursuit was unjustifiable .

N. POULANTZAS ,

THE RIGHT OF HOT PURSUIT IN INTERNATIONAL LAW 209 (1969)

[hereinafter cited as POULANTZAS).

Therefore, Latia lost its

right to rely on the doctrine of hot pursuit.

Gatherer was outside Latia ' s territorial sea in an area

beyond its continental shelf.

Latia, therefore, had no

jurisdiction to interfere with Gatherer's activities.

Assum-

ing, arguendo, that this Court finds that the actions took

place within Latia's territorial sea or above its continental

shelf , Latia's responses were unjustified.

Only responses

which do not involve the use of armed force, i.e. pacific reprisals, conform with Latia's obligations as a member of the

United Nations.

2 G. SCHWARTZENBERGER, INTERNATIONAL LAW 58

22

(1968); U.N. CHARTER art. 51.

A·s suming, further, that international law permits Latia

to use force, nevertheless, Latia's actions were unlawful.

Latia's positive reprisal by use of excessive force constituted a violation of international law, because the act must

'be in proportion to the wrong.

LAW

§

2 L. OPPENHEIM, INTERNATIONAL

389, at 140-41 (7th ed. H. Lauterpacht 1952) .

A state

may exert only the amount of compulsion necessary to achieve

its ends .

Id.Latia ' s unprovoked attack, which rendered the

mining rig inoperative and injured its crew members, was excessive by any standard.

Even if Industria's actions had

been unlawful, Latia's use of unjustifiable force permits

Industria to be indemnified for its costs a.nd damages.

POULANTZAS

26~-65.

Failure to observe a rule of international

law gives a state a claim for satisfaction whether it be

diplomatic in character or in the form of indemnity or reparation.

J. STARKE, AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNATIONAL LAW 20-21

(7th ed. 1972);

~

also CHS art . 23 (7).

For the above reasons, this Court should award Industria

return of the nodules, return of Gatherer, reimbursement of

all fines and assessments, and compensation for all other

costs including lost profits on the mining operation and prejudgment interest .

POULANTZAS 265.

The Court would also be

justified in awarding Industria moral damages.

Claim of the

British Ship "I'm Alone" v. United States, Report of Commissioners, 29 AM. J. INT'L L. 326, 331 (1935); Naulila Incident

23

Arbitration 409, 2 U.N.R.I.A.A. 1012 (1928), 6 HACKWORTH,

INTERNATIONAL LAW 154 (1943).

C O ' N C L U S ION

WHEREFORE, for , the reasons set forth above, Applicant

respectfully prays that the International Court of Justice

render its decision in favor of Industria, finding that:

(1)

Tract #1 is outside Latia's jurisdiction.

(2)

Latia ' s actions against Industrian ships violated the

freedom of the seas.

(3)

Industria is entitled to the return of all confiscated

property, reimbursement of all fines and assessments,

compensation for lost profits, and moral damages.

(4)

Industria may exploit Tract #1 under a DOMA license.

Respectfully submitted,

Team No. 1

Agents fo~ Industria

,

/

/

/

.

"\-"r-'~,--",. , ... '

ClJ~;;- -~

I,," ....... "

I

I

I"

-

J

..'''C,

:;_..

I'

I

--1

~

........T"'-..........

I' ...... ,

\ '" \ \ \\

\.)

,...'<' \

, 4..

'-

.

~

. s~ I.- '

'.

. ...-:,

( DOMIN. REP, '.

I'

ok t·

......

PUERTO

RICO

.

_

-

,

-",

A1

- - ~ ~,

V I / "..""

~ ..("'LEEWARD

/ of r.

ISLANDS"

SEA:'~

/ .tt 'I}

~,.,- -r<:.., ::."":.c........'" j'w

t

/

I, /""' , - -....:-_....r.'

... /" / I

.........

{V""~---3Il

--t-'"

\

.ft\. ..... _ -4..::-: ..... /

I .......

\•~. . . . . . _ 1.

,.,'"

,

... ..

1, '..

.. _

".,

WINOWARD

ISLANDS

,-.L. - / ,,- /

\ ,'"

...

// ~;:..,

/ .

\- - - " ,

-/

I

\ )

~/

/

I/'\

c:;z;;I_V'/ "I"'I

\

,

/ :r\J ' "j- ....... ,

/ /....-7 ~/

......~~\

\

_"7'_

.j.,...... :•. /

,.. 1i~'

:":""" ': ' .

\

--- ,

\,,-"

"

CARIBBEAN

r~·~.I~H .,.:,.~

1/

, .. '

, ../

I

-----j/

lo-.

-

.'

I',"""

.. " " ~_,,,-

~1//

"..- --..;:-,

..... ,

.. ....... ~,

----,.'<""J

._

..... - - - - ' /

',\

/.......

II

•

'- - _ . - ...." ' /

:JJ-..-

H

i.; ...• ..•."

'-

.

VENEZU.El.A

.~' -">

: .- . ,:-:~ .. '

~,

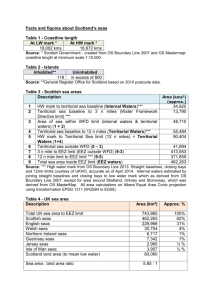

The Caribbean Sea and a Two-Hundred-Mile Limit

B. BRITTIN . & L. WATSON, INTERNATIONAL LAW

FOR SEAGOING OFFICERS 83 (3d ed. 1972)

[A hypothetical division: The adverse effects of a

universal 200-mile territorial sea, as claimed by Latia.)

...

IV

JAMAICA

~

HIGH

SEAS

-~~12MllES

NICARAGUA

o

110

WW

120

240

MILES

The Caribbean Sea and a Twelve-Mile Limit

B. BRITTIN & L. WATSON, INTERNATIONAL LAW

FOR SEAGOING OFFICERS 80 (3d ed . 1972)

[The desirable effects of allowing

universal extensions to the maximum

twelve-mile limit, as recognized by

international law.]

No. 1974-00 1

IN THE ' INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE

AT THE PEACE PALACE; THE HAGUE; NETHERLANDS

March Terin, 1974

THE,','STATE OF INDUSTRIA,

',

,

Applicant:

THE STATE OF LATIA,

Respondent.

On Submission to the

.1nternationaf Court 'of Justice

:'COUNTER~MEMORIAL FOR THE RESPONDENT

:; ':

,

"

: ,.' .

. '. , ;

,

.'

, "-

'

. '",

•

.'

•

'

.

,

.

'

!

" ,'

,

':

TEAM NO . .1

Agents fot Latia,

I N D E X

Page

Index of Authorities

ii

Jurisdiction • • • •

viii

• •

Questions Presented

•

ix

•

Statement of Facts •

ix

Summary of Argument

•

ix

Argument and Authorities •

1

I.

LATIA HAS SOVEREIGNTY OVER TRACT #1

UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW

A.

International law does not prohibit

Latia from exercising exclusive sovereignty over a 200-mile territorial

sea. . . . . .. ..

..

.. .. .. .. .. .

1

Latia's exercise of sovereignty over

Tract #1 is justified under international law by the continental shelf

doctrine .. .. .. .. .. . .. . .. .. .. . .. ..

9

'Latia' s establishment of a 300-mile

economic resource zone is recognized

under international law • • • • • •

16

..

B.

C.

II .

1

.

INDUSTRIA BREACHED INTERNATIONAL LAW BY

GRANTING A LICENSE WHICH AUTHORIZED THE

VIOLATION OF LATIA'S SOVEREIGNTY OVER

TRACT #1 ..

A.

B.

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

20

The licensing of Tract #1 violates

international law by not respecting

Latia's territory and ignoring the

purpose of the 1958 Conventions

20

Industria's breach of Latia's sovereignty violated both DOMA and international law, justifying Latia's actions in preventing mining operations

' and protecting its la~ful interests.

23

. . . . . . .. .. .. .. . .. .. . .. .. .. .. ..

25

Conclusion • ..

ii

I N D E X

0 F

AUT H 0 R I TIE S

Page

Treaties and U.N. Resolutions

Deep Ocean Mining Act (1973)

DOHA

§

1 .

DOHA

§

2(b)

DOMA S 4 • •

DOMA

§

4 (c) •

DOHA

§

6

•

8

•

..

21

21, 23

•

• • •

•

•

•

•

•

.

20

21, 22, 23

•

22

DOHA S 7

21

•

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, art . 2(1) (a),

done May 23 , 1969, U.N. Doc. A/Conf. 39/27.

Vienna Convention art . 26

....

~

.. .. .. .. ..

8, 23

• •

23

Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone ,

done April 29 , 1958 , T . 1.A.S . 5639; 516 U.N . T.S.

'2l5"5 " . .. .. . . . . . .. .. . .. . .. .

4

Convention on the Territorial Sea art. 1

8

Convention on the Territorial Sea art . 2

6, 8

Convention on the Territorial Sea art . 14

7

Convention on the Territorial Sea art. 16 -

7

Convention on the Territorial Sea art. 16 ( 1 )

8

Convention on the Territor i al Sea art . 24.

. .

Convention on the High Seas, done .Apri1 29 , 1958 ,

. . .. 0\ .. . . . .

450 U.N.T.S . 82

....

. .

16

.

Convention on the Continental Shelf, done April 28,

195 B, T. 1. A. S • No • 5578; 499 u. N:T:S . 311

Convention on the

. ..

20

• • • • 9

Continental Shelf art. 1 • • • • • 9, 14, 23

iii

Treaties and U.N. Resolutions (Cont.)

Page

Convention on the Continental Shelf art. 2(1)

10, 15

·

Convention on the Continental Shelf art. 2(2) •

U.N. CHARTER art. 2, para. 3

15

•

23

• •

U.N. CHARTER art. 33, para. 1 • •

•

G.A. Res. 2749, 25 U.N. GAOR U.N. Doc. A/C./544

·...

(1970)

•••••••••••.•...

23

•

21

Statutes

Deep Seabed Hard Minerals Resources Act, S.2801,

92d Cong., 1st Sess . (1971)

• • • •••••

·..

17

Cases

North Sea Continental Shelf Cases, [1969] I.C.J.

South West Africa Cases, [1966] I.C.J.

Fisheries Case ,

11

• • •

[1951] I.C.J • •

2

•

• • • • 6

•

In the Matter of an Arbitration Between Petroleum

Development (Trucial Coast) Ltd. and the Sheikh

of Abu Dhabi, 1 INT'L & COMPo L. Q. 247 (1952)

(full text rep'd). • • • • • • • • •

•••••

12

Treatises

J. ANDRASSY , INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE RESOURCES OF

THE SEA (1970) • • • • • • • • •

• • • • • • 6, 11

O. ASAMOAH, THE LEGAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE DECLARATIONS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE UNITED

NATIONS (1966) • •

•

•

• •

• •

. ..

.

.

.

22

"\

W. COPLIN, THE FUNCTIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW

(1966)

•

•

• •

• •

.

... . ...........

.

2

H. HALL, INTERNATIONAL LAW (Higgin's 8th ed.

(1924)

•

e.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

••

23

iv

Treatises (Cont.)

Page

D. JOHNSTON & E. GOLD, THE ECONOMIC ZONE IN THE

. LAW OF THE SEA: SURVEY, ANALYSIS AND

APPRAISAL OF CURRENT TRENDS , OCCASIONAL

PAPER No. 17, (1973) . • • • • • • . • • • 16, 18, 19

Laque, Deep Ocean Mining: Prospects and Anticipated

Short-Term Benefits, in PACEM IN MARIBUS 131

(E. Borgese ed. 1972)

•••••••••••

H. LAUTERPACHT, INTERNATIONAL LAW (E. Lauterpacht

ed. 1970)

.. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

5

..

..... .

4

M. MCDOUGAL & W. BURKE, PUBLIC ORDER OF THE OCEANS

(1962)

.

.

.

..

.

..

..

..

.

..

..

..

..

.

.

.

.

8, 13

.

2 NEW DIRECTIONS IN THE LAW OF THE SEA (S. Lay,

R. Churchill, & M. Nordquist ed. 1973) • •

•

1 D. O'CONNELL , INTERNATIONAL LAW (2d ed. 1970) •

12

6

S . ODA , INTERNATIONAL CONTROL OF SEA RESOURCES

(1963)

.

....

......

" ..

....

.. 14

1 L. OPPENHEIM, INTERNATIONAL LAW (8th ed. H.

Lauterpacht 1955)

•• •

• • • • • •

..

.. ..

.. 24

2 L. OPPENHEIM, INTERNATIOl~AL LAW (7th ed . H.

Lauterpacht 1952)

• • •

••• ••••

•

24

C . RONNING, LAW AND POLITICS IN INTER-AMERICAN

DIPLOMACY (1963) • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

18

0

"

..

1 G. SCHWARTZENBERGER , INTERNATIONAL LAW (3d ed .

1957) . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

2 G. SCHWARTZENBERGER, INTERNATIONAL LAW (1968)

2

•

24

Z. SLOUKA , INTERNATIONAL CUSTOM AND THE CONTINENTAL

SHELF (1968) • • • • • . . • • • • • •

J. 'STARKE , AN INTRODUCTION TO INTER~ATIONAL LAW

(7th ed . 1972) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

4 M. WHITEMAN, DIGEST OF INTERNATIONAL LAW (1965)

5 M. WHITEMAN, DIGEST OF INTERNATIONAL LAW (1965)

10

.. .. 13

••

7

24

v

Periodicals

Page

Auburn ,T

~ih:;:e:-il'-i9r-:.7:;3~C::.o~n.::f~e:;:r~e~n:::c~e:.:-:o:::;n~t=h:;;e7'L~a:.:w:--;0<if~t2h=-e=-.::::s.::e~a

in the Light of Current Trends in State

Seabed Practice, 50 CANADIAN B. REV. 87

(1972) . .

. . .

• • 5, 14

. . . .....

Bernfeld, Developing the Resources of the Sea-Security of Investment, 2 INT'L. LAW. 67

(1967) . • . . . . •

. . . . · . 2,

Brown & Fabian, Diplomats at Sea, 52 FOREIGN

AFFAIRS 301 (1974) • • • . • . • • • • •

·..

f;I

13

• • • • •

Goldie, International Law of the Sea--A Review

of States' Offshore Claims and Competences,

24 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REV. 43 (Feb. 1972).

19

• •• 3

Heinzen, The Three-Mile Limit: Preserving the

Freedom of the Seas, 11 STAN. L. REV.

597 (1959)

............ .

5

Knight, The Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources

Act--A Neyative View, 10 SAN DIEGO L. REV.

446 (1973

••.•••.•.••••••

• 17, 22

Lecuona, The E uador Fisheries Dis ute (A new

approach to an old problem, 2 J. MARITIME

L. & COMM. 91 (1970)

••••••

..

4

H. Lauterpacht, soverei~nty Over Submarine Areas,

27 BRIT. Y. B. INT L L. 1950, at 376 (1951) • • • 12

Laylan, Past, Present, and Future Developments of

the Customar International Law of the Sea and

Deep Seabed,S INT L LAW. 442

• • •

1

Report of the Australian Branch Committee on Deep

Sea Mining, AUSTL. Y. B. INT'L L. 1968-69,

at 149

(1971)

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. 11

Note, Seizure of United States Fishing Vessels--A

Status of the Wet War, 6 SAN ~EGO L. REV.

428 (1969) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

Shuman, Pacific Fisheries Conservation Conventions,

2 SYDNEY L. REV. 436 (1958) • • • • • • • • ••

2

vi

Periodicals (Cont.)

Page

Young, The Develoeing Law of the Deep Seabed:

American Att1tudes, 5 TEX. INT'L L. F.

235 (1958) • • • • • • • • • •

....

• • • .

• 11

Young, The Geneva Convention on the Continental

Shelf: A First Impression, 52 AM. J. INT'L

L. 733 (1958)

••••••••

.......

9, 14

Miscellaneous

African States: Conclusions of the Regional

Seminar on the Law of the Sea, 12 INT'L

LEG. MAT. 210 (1973) • • • • •

.....

.

.

COMMON TO STUDY THE ORG. OF PEACE, Twenty-First

Report, THE UNITED NATIONS AND THE BED OF THE

SEA (II) (1970). • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

. . 19

10, 12

Declaration of Santo Domingo , 11 INT'L LEG. MAT.

89 2 (1972) • • . • • • .

• • • •

• • • 19

FOURTH ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE LAW OF THE SEA

INSTITUTE, THE LAW OF THE SEA: NATIONAL

POLICY RECOMMEDNATIONS 152 (L . Alexander ed.

1969) . . . . . . . .

.

.

...

~

. ......

.

. 17

Inter-American Council of Jurists, Third Meetins,

Doc. A/AC. 4/102, at 249 (1956)

3

Inter-American Council of Jurists, Third Meetins,

Doc. A/AC. 4/Add. 1, at 252 (1956 )

• •

3

. · · · · · '. . .

·····

Inter-American Council of Jurists, Third Meetins,

Doc. A/CN. 4/102, at 249 (1956) • •

•

•

·

··

•

1

Inter-American Juridical Comm., Opinion on the

Breadth of the Territorial Sea, [1966] O.A.S.

/OD 0.E.A./Ser.I/VI.2 (English) CIJ-80 • • • • • . 18

Int'l Law Comm'n, Report, 11 U.N. ~OR,

Supp. 9, U.N. Doc. A/31S9

(1956) • • • • • • • • • • • • • 4, 7, 9, 13, 15, 21

11 INT 'L LEG. MAT 226 (1972)

•

.......

24

vii

Miscellaneous (Cont.)

Page

INTERIM REP. OF NAT'L PETROLEUM COUNCIL,

July 9, 1968, at 6 • • • • • • • • • • • •

·...

League of Nations Off. J., Doc . C. 196 . M.70.V ,

at 122 (1927) . . • . • • • . • • • • .

1 PUB. LAND. L. REV.COMM'N, STUDY OF OUTER

CONTINENTAL SHELF LANDS OF THE UNITED

••••

STATES pt. 2, (1st Rev . 1969)

..

Santiago Declaration, U.N. Doc. ST/LEA/SER.8/6 ,

223-24 (1952) • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .

11

• 5

• •

11, 14

·. ..

24 U.N. GAOR, Rep. of the Comm. on the Peaceful

Uses of the Sea-bed and the Ocean Floor

Beyond the Limits of Nat ' l Jurisd., Supp. 22,

at 108, U.N. Doc. A/7622 (1969)

••••• ,

17 U.N. GAOR A/5344/Add. 1, A/L.412/Rev. 2 (1962)

18

10

•

17

viii

BEFORE THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE

MARCH TERM

1974

CASE NO. 1974-001

THE STATE OF INDUSTRIA,

v.

Applicant

THE STATE OF LATIA ,

Respondent

COUNTER-MEMORIAL FOR THE RESPONDENT

J URI S D I C T ION

The parties have agreed to submit this dispute to the

International CouFtof Justice for its determination.

ix

o

I.

II.

U EST ION S

PRE SEN TED

WHETHER LATIA HAS SOVEREIGNTY OVER TRACT II UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW?

WHETHER INDUSTRIA BREACHED INTERNATIONAL LAW BY GRANTING

A LICENSE WHICH AUTHORIZED THE VIOLATION OF LATIA'S SOVEREIGNTY OVER TRACT II?

o

S TAT E MEN T

F ACT S

F

The parties have stipulated the .facts before the Court.

SUMMARY

o

F

ARGUMENT

Latia has sovereignty over Tract #1 under international law .

International law does not prohibit Latia from exercising exclusive sovereignty over a 200-mile territorial sea.

Latia's exercise of sovereignty over Tract #1 is justified

under international law by the continental shelf doctrine.

Because Latia has sovereignty over its continental shelf, Latia

has lawfully exercised those rights necessary to ensure that

sovereignty.

Latia's establishment of a 300-mile economic resource zone

is recognized under international law.

Industria breached international law by granting a license

which authorized the violation of Latia's sovereignty over Tract

u.

Industria's breach of Latia's' sovereignty justified Latia's

\

actions preventing mining operations and protecting its lawful

interests.

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES

I.

LATIA HAS SOVEREIGNTY OVER TRACT tl UNDER INTERNATIONAL

LAW .

A.

International law does not erohibit Latia from

over a 200-mile

exercis~ng exclusive sovere~gnty

terr~torial sea.

In 1966, Latia lawfully extended the limits of its territorial sea.

Its action is justified by the customary rule

that territorial seas have no uniform limits.

This custom-

ary rule was codified by the 1958 Conference on the Law of

the Sea.

Latia's action is further justified by its conform-

ity with the criterion by which any such extension must be

judged:

reasonableness.

1.

Customary international law prescribes no uniform

limits for territorial seas.

The customary rule limiting the breadth of a territorial

sea is founded on the criterion of reasonableness.

Laylan,

Pa st, Present, and Future Development of the Customary International Law of the Sea and Deep Seabed, 5 -INT'L LAW. 442,

444 (1971).

Historically, the three-mile limit was widely

applied because it adequately met the needs of earlier times.

While the three-mile limit was adopted as a reasonable measure of self-defense, states

motiva~ed

by other needs tradi-

tionally have acknowledged greater limits.

Such limits have

been recognized as being based on geographical, economic ,

biological, and security considerations.

Inter-American

2

Council of Jurists, Third Meeting, Doc, A/CN. 4/102, at 249

(1956).

The three-mile limit, which was never a universally

applicable rule of international law, is no longer reasonable.

No te, Seizure of United States Fishing Vessels--A Status of

the wet War, 6 SAN DIEGO L. REV, 428, 430 (1969).

Three-mile

territorial seas no longer guarantee the security of coastal

states against aggression by belligerent warships.

1 G.

SCHWARTZENBERGER, INTERNATIONAL LAW 351 (3d ed. 1957).

For

centuries the three-mile limit has been based on the pre-supposition that ocean resources are inexhaustible.

This miscon-

ception is no longer tenable in view of modern technology.

Shuman, Pacific Fishery Conservation Conventions, 2 SYDNEY L .

REV. 436 (1958).

Technological developments have opened the

ocean floor to wholesale exploitation of resources to the point

of exhaustion, rendering the three-mile limit obsolete.

Bernfeld, Developing the Resources of the Sea--Security of

Investment, 2 INT'L LAW. 67', 69 (1967).

The traditional bases for restricted territorial-sea limits

are no longer applicable because they do not meet the reasonable

needs of coastal states ,

When, as in this, 'case, the basis for

a rule no longer exists, the rule becomes invalid.

See W.

COPLIN, THE FUNCTIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 13-18 (1966).

Since the vast majority of nations cannot utilize the high

seas as industrialized states can, 'the three-mile rule does

not represent the interests of the world community and is contrary to international law.

South West Africa Cases,

[1966]

3

I.C.J. 248.

Accordingly, the territorial seas of most coast-

al states now exceed three miles.

Presently, Latia is one of

over eighty nations which have territorial seas extending beyond three miles.

Goldie, International Law of the Sea--A

Review of States' Offshore Claims and Competences, 24 NAVAL

WAR COLLEGE REV. 43, 66 (Feb. 1972).

Thus, Latia is not bound

to follow the three-mile rule.

2.

The 1958 Conventions codified the rule that

international law prescribes no uniform

limits for territorial seas .

The conference at Ciudad Trujillo in 1956 is representative of the law concerning the limits of territorial seas

existing prior to the 1958 Conventions.

The conference noted

a diversity of positions as to the breadth of territorial seas

under international law.

Inter-American Council of Jurists,

Third Meeting, Doc. A/AC. '4/Add. 1, at 252 (1956).

In the

same year, the Inter-American Council of Jurists passed a resolution declaring that the three-mile limit was not a general

rule of international law, and that enlargement of the territorial sea beyond three miles was justifiable.

Further, each

nation was to establish its territorial waters within reasonable limits, taking into account the geographical, geological,

biological, and economic needs of its population.

Inter-

American Council of Jurists, Third "Meeting,

Doc. A/AC. 4/102,

,

at 249 (1956).

The 1958 Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous

Zone recognized that there are no uniform limits to the

4

territorial sea.

Contiguous Zone,

Convention on the Territorial Sea and

~

April 29, 1958, T.I.A.S. 5639; 516

U.N.T.S. 205 [hereinafter cited as CTSCZ]; Int'l Law Comm'n,

Report, 11 U.N. GAOR, Supp. 9, U.N. Doc. A/3l59 (1956)

[hereinafter cited as 11 I.L.C.].

This convention is the most

successful codification of the law on territorial seas to date.

H. LAUTERPACHT, INTERNATIONAL LAW 98 (E. Lauterpacht ed. 1970).

The CTSCZ did not set any fixed limit on the breadth of

territorial seas.

This convention reflects the fact that a

rigid delimitation would in itself be unreasonable because it

fails to take into account the particular needs of individual

c o astal states.

Should this Court require Latia to refrain

from extending the limits of its jurisdiction, the law of the

sea would revert to pre-convention days when major maritime

powers sought ' a rigid three-mile delimitation.

then be free to exploit the ocean at will .

They would

Lecuona, The Ecua-

dor Fisheries Dispute (A new approach to an old problem), 2 J.

MARITIME L. & COMM. 91, 111-113 (1970).

Reasonableness, the

only viable standard for evaluating a state's actions, would

be eliminated from international law.