S VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW IR

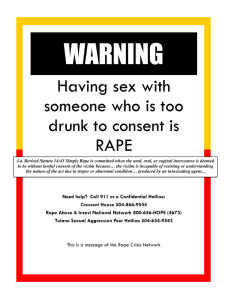

advertisement