Can States Enforce Their Civil Rights Laws Against National Banks? BANKING

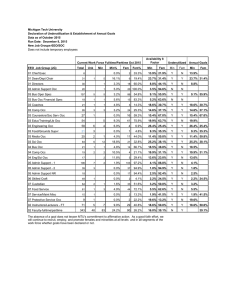

advertisement

BANKING Can States Enforce Their Civil Rights Laws Against National Banks? by Ann Graham PREVIEW of United States Supreme Court Cases, pages 435-439. © 2009 American Bar Association. employ a two-step analysis to determine the validity of a federal Ann Graham is a professor of law agency's interpretation of a federal at Texas Tech University School of statute. First, the courts look to the Law. In addition to private law statute to determine whether practice representing financial Congress has directly spoken to the institutions, she has served in ,. precise question. If the intent of FDIC's Washington Office, as Congress is clear, the courts must FDIC's Dallas Regional Counsel, follow it. In the second step, if the as General Counsel for the Texas statute is silent or ambiguous, the Department of Banking and as courts must defer to the federal Chief Regulatory Counsel for agency's interpretation if it is perthe Texas Bankers Association. missible-not the best interpretaShe can be reached at tion or even one that the court ann.graham@ttu.edu, blogging at would prefer. This doctrine comes http://lawprofessors. typepad.coml from the 1984 Supreme Court opinbankingl, or (806) 742-3990, ion in Chevron USA Inc. v. Natural ext. 295. Resources Defense Council, 467 U.S. 837. ISSUES Should the OCC's regulation, 12 C.F.R. § 7.4000, be upheld because of "Chevron deference" or should the Court determine that "Chevron deference" is not warranted because the OCC's interpretation deprives the states of authority to enforce state laws against a national bank even when the laws themselves have not been preempted? The Office of Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the federal agency that regulates national banks, contends that the New York attorney general cannot interfere with the OCC's exclusive "visitorial power" over national banks and that the states may not take advantage of an exception in federal statute that makes national banks subject to powers "vested in the courts of justice." The attorney general counters that the OCC regulation at issue in this case is invalid because it is inconsistent with the National Bank Act and prior case law and, further, that it is not entitled to deference from the courts. In this case, the attorney general of the state of New York is challenging a regulation adopted by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), which was invoked to prohibit a state from investigating or filing suit against a national bank when the state is seeking to enforce a state antidiscrimination law. The parties agree that the state law itself is not preempted, only the state's enforcement authority. (Continued on Page 436) CUOMO V. CLEARING HOUSE L.L. C. No. 08-453 ASSOCIATION, DOCKET ARGUMENT DATE: The case raises issues concerning the Chevron Doctrine and "Chevron deference" under which courts APRlL 28, 2009 FROM: THE SECOND CIRCUIT 435 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1571628 Is the OCC's regulation invalid because it is inconsistent with the authoritative construction of the National Bank Act in First National Bank in St. Louis 'V. Missouri, 262 U.S. 640 (1924)? FACTS This case arises out of an investigation by then-Attorney General Spitzer into possible racial discrimination by national banks located in the state of New York with regard to mortgage loans. In 2005, new data became publicly available under the federal Home Mortgage Disclosure Act relating to race, ethnicity, gender, and income of loan applicants as well as interest rate charged (the HMDA data). The HMDA data do not include all information necessary for prudent underwriting and pricing; therefore, the data do not conclUSively establish lending discrimination in violation of New York State antidiscrimination laws or federal antidiscrimination laws. In March 2005, the New York attorney general's office sent "letters of inquiry" (in lieu of formal subpoena) to national banks, including Wells Fargo, HSBC, J.P. Morgan Chase, Citibank, and others that are members of the financial institution trade association Clearing House ASSOCiation, L.L.C. These letters stated that each bank's II11DA data indicated racial disparities in interest rates charged for white borrowers as compared with African American and Hispanic borrowers. The letters requested nonpubHc information that could be used to prove or disprove discrimination with regard to real estate loans made in New York State. The Clearing House Association, L.L.C., and the OCC responded by filing separate suits in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on June 16, 2005. They sought to bar the New York attorney general's investigation because they said it infringed on OCC's exclusive visitorial powers over national banks. OCC had adopted a regulation in 2004 (12 C.F.R. § 7.4000) that purports to "clarify" and interpret federal law to prohibit the states from going to court to enforce state laws against national banks. The New York attorney general filed a counterclaim asking to have the OCC's visitorial powers regulation declared invalid as arbitrary, capricious, and contrary to law, under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), 5 U.S.C. § 706. of the National Bank Act: "No national bank shall be subject to any visitorial powers except as authorized by Federal law, vested in the courts of justice or such as shall be, or have been exercised or directed by Congress .... " The OCC, which charters and regulates national banks, adopted a new regulation in 2004, 12 U.S.C. § 70001, which defines the OCC's exclusive "visitorial powers" over national banks and explains what the exception which subjects national banks to the exercise of visitorial powers "vested in the courts of justice" means. The suits filed by OCC and Clearing House were consolidated. The district court dismissed the attorney general's challenge to the OCC's regulation. The district court granted the declaratory and injunctive relief sought by OCC and Clearing House, based on Chevron deference to OCC's regulation interpreting federa1law. The OCC's interpretation bars all state investigative and enforcement actions, not only by administrative proceeding but also by filing suit in the courts, when the state seeks to enforce state laws dealing with lending by national banks. The new regulation purports to be merely a clarification of existing law. The 2004 regulation clearly provides that "visitorial powers" include "(i) Examination of a bank; (ii) Inspection of a bank's books and records; (iii) Regulation and supervision of activities authorized or permitted pursuant to federal banking law; and (iv) Enforcing compliance with any applicable federal or state laws concerning those activities." A three-judge panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that the District Court did not err in deferring to the OCC's interpretation of federal law as set forth in its regulation. The majority opinion, in which two judges joined, rejected the attorney general's argument that the OCC's'interpretation was not entitled to Chevron deference because it involves a preemption determination made by the agency in-the-ahsence-ef-a-clear-statement of congressional intent. CASE ANALYSIS This case turns on the interpretation of 12 U.S.C. § 484, a provision OCC's regulation explains the "courts of justice" exception as follows: "National banks are subject to such visitorial powers as are vested in the courts of justice. This exception pertains to the powers inherent in the judiciary and does not grant state or other governmental authorities any right to inspect, superint~£1d, direct, regulate or compel compliance by a national bank with respect to any law, regarding the content or conduct of activities authorized for national banks under Federal law." The New York attorney general highlights_the follOwing fo:ur Leasons for gr~nting Supreme Court review:-(I) The Second Circuit's decision squarely conflicts with First National Bank in St. Louis 'V. Missouri, which held that the 436 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1571628 Issue No.7 Volume 36 National Bank Act does not prevent states from enforcing their own nonpreempted laws; (2) The case presents the important and unresolved question of when, if at all, Chevron deference is due to a regulation declaring the preemptive scope of a federal statute; (3) The Second Circuit's decision profoundly shifts the federal-state balance and deprives states of their core sovereign power to enforce their non preempted laws against national banks; and (4) The OCC's interpretation of federal statute, 12 U.S.C. § 484, effectively immunizes national banks from enforcement of state consumer protection and fair lending laws. A closer analysis of both the majority and dissenting opinions from the Second Circuit in Cuomo 'V. The Clearing House Association sets the stage for the Supreme Court's review of this case. To begin, the majority opinion clearly rejected the attorney general's reliance on the 1991 Supreme Court case Gregory 'V. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452, and its gUiding principle that, "If Congress intends to alter the usual constitutional balance between the states and the federal government, it must make its intention to do so unmistakably clear in the language of the statute." Another threshold question for the Second Circuit was whether a presumption against preemption should apply. The majority concluded that, although ordinarily a presumption against preemption applies to regulation traditionally allocated to the states, "this presumption 'disappears' in the context of national bank regulation." The majority also refused to apply the doctrine of constitutional aVOidance, which instructs a court that, when an otherwise acceptable statutory construction would raise serious constitutional problems, the court should construe the statute to avoid constitutional issues unless Congress plainly intended otherwise. The Second Circuit acknowledged a 2001 Supreme Court case noting "heightened" necessity for a clear statement from Congress "where the administrative interpretation alters the federal-state framework by permitting federal encroachment upon a traditional state power." Solid Waste Agency of N. Cook County 'V. U.s. Army Corps of Eng'rs, 531 U.S. 159, 173. However, the majority opinion concluded that a clear congressional statement of preemption was not required to justify the OCC's regulation. Guthrie 'V. Harkness, 199 U.S. 148 (1905), represents the Supreme Court's first interpretation of "visitorial powers" and concerned the issue of whether the National Bank Act precludes an individual from bringing a lawsuit to require permission to inspect the books and records of a national bank. The attorney general would extend Guthrie to permit not only a private citizen but also a state official to bring a lawsuit to inspect the books and records of a national bank for a limited purpose. The Second Circuit's majority opinion rejects that argument. The Second Circuit relied on the 2007 Supreme Court decision in, Watters 'V. Wachovia Bank, 550 U.S. 1, in upholding the OCC's regulation in this case, even while acknowledging that Watters does not directly address the questions at issue here. In Watter$, a Michigan statute required all mortgage lenders, other than national banks, to register with the state financial institutions regulator and make disclosures. The Watters opinion held that state laws are preempted with respect to operating subsidiaries of national banks to the same extent that they are for the national bank itself. The Supreme Court in Watters quite surpriSingly skipped over the question of whether the OCC regulation there was entitled to Chevron deference and found the source of preemption in the National Bank Act itself. The Second Circuit says that the Supreme Court in Watters "implied" that investigation and enforcement by state officials are just as much a part of visitorial authority as the Michigan mortgage lender registration statute. It will be enlightening to have the Supreme Court adopt or reject this "implication." It will also be interesting to see whether the Supreme Court will provide gUidance on the Chevron Doctrine. Further, the Second Circuit rejected the attorney general's argument that no deference is owed to the OCC's regulation because it interprets purely legal concepts rather than technical matters within the agency's expertise. The Supreme Court could very well address the issue of whether judicial deference is warranted when a federal agency, by regulation interpreting a federal statute, announces preemption of a state law. Preemption is a legal issue rather than a technical issue. The Second Circuit's dissenting opinion by Judge Cardamone forcefully disagrees with the majority. His dissent begins with his view that the OCC has "altered the compact between the state and national governments." One of his key concerns is that the constitutional concept of federalism, an "indispensable component of our free society," is at risk. He raises Tenth Amendment issues that were raised but dismissed in Watters. Judge Cardamone views the National Bank Act, not as displacing the state banking system but rather as establishing the dual banking system in which state and national (Continued on Page 438) American Bar Association 437 banks coexist in relative "competitive equality," quoting the Supreme Court in First National Bank in Plant City 'D. Dickinson, 396 U.S. 192 (1969). Judge Cardamone distinguishes "visitorial powers" that include analyzing national bank's activities under their national banking charter from what he sees as the New York attorney general's exercise of authority under the state's police power to investigate civil rights violations being committed by New York entities in New York. Judge Cardamone finds support in the 1994 Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act for his conclusion that Congress specifically subjected interstate branches of national banks to the laws of their host states in the areas of community reinvestment, consumer protection, fair lending, and intrastate branching, including the follOWing statement in the Conference Report: "States have a strong interest in the activities and operations of depository institutions doing business within their jurisdictions, regardless of the type of charter an institution holds. In particular, States have a legitimate interest in protecting the rights of their consumers, businesses, and communities ... Congress does not intend that the Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 alter this balance and thereby weaken States' authority to protect the interests of their consumers, bUSinesses, or communities. " First National Bank in St. Louis 'D. Missouri, 263 U.S. 640 (1924), is a cornerstone of Judge Cardamone's dissent as it is for the New York attorney general'scas~ before the Supreme Court. In St. Louis, the IvIissouri attorney general brought suit against a national bank in state court to enforce a state law prohibiting branch banking. The national bank contended that even if the state law could be validly applied to the national bank, the attorney general could not sue the national bank to enforce it. The Supreme Court in St. Louis upheld the attorney general's position in that case. OCC, however, would distinguish that case on grounds that branch banking was not authorized for national banks at that time. The New York attorney general counters that discriminatory lending is not authorized for national banks at this time, but the OCC argues that the focus should be on lending itself as a core banking function authorized for national banks rather than the manner of performing that function illegally. The attorney general points out that it was not until 1966 that Congress first gave the federal financial institution regulators, including the OCC, power to enforce state law, with no suggestion that the new power to enforce state law administratively was meant to displace state enforcement of state laws against national banks. According to the attorney general, OCC's regulation adopted in 1971 expressly acknowledged the authority to require production of national bank records using normal judicial procedures. That regulation was broadened in 1999 to limit, for the first time, a state's ability to enforce its own valid and nonpreempted laws against national banks. The New York attorney general identifies numerous examples over the past several decades in which the New York attorney general has investigated and settled cases against national banks involving enforcement of state consumer protection laws, pointing out that until this case, national banks_c_ooperat~d-yYithJ;h~attorney general's investigations. The OCC relies' on the Supreme Court opinion in National Cable & Telecommunications Ass'n 'D. Brand 438 X Internet Services, 545 U.S. (2005), for the proposition that a federal agency is still entitled to Che'Cron deference even when the agency adopts a new statutory interpretation that differs from the judicial interpretation previously reached by a federal court. The OCC dismisses all cases that predate the 2004 regulation on the same grounds. Another OCC argument is that when the state is precluded from exercising visitorial powers over a national bank directly, it should not be permitted to achieve the same result by filing a lawsuit. However, the attorney general's response is that if private parties can sue a national bank for violations of state law, the state attorney general should not be precluded from doing so. SIGNIFICANCE Intriguing questions abound in this case. As the multipliCity of amicus briefs filed indicates, many different interests beyond those of the OCC and the New York attorney general will be affected. Particularly in light of the subprime lending criSiS, state financial institution regulators and state attorneys general want to protect their citizens from predatory or discriminatory lending by any financial institution doing business in their states. Forty-nine states joined in an amic:!:ls brief opposing the OCC regulation at issue in this case. They argue the basic prinCiples of federalism and our dual banking system. They see the potential for incursion on state sovereignty as highly undesirable both from a constitutional standpoint and from the practical perspective that state government is closer to its own citizens and can better address problems \vithin its own boundaries-although they welcome additional (but not preclusive) enforcement help from the federal Issue No.7 Volume 36 agency. The Conference of State Bank Supervisors sharply questions whether the OCC has the resources or the will to be the primary enforcer of 50 different state consumer protection and antidiscrimination statutes. State regulators are troubled that the OCC uses its power to preempt state laws for national banks as a marketing tool to recruit banks to the national charter, which they characterize as a selfinterested campaign to expand the OCC's jurisdiction. They perceive that the OCC has issued a series of preemption opinions, regulations, and positions in litigation that constitute a deliberate, step-by-step accretion of power to the federal agency and a concomitant diminishment of traditional state authority. The presumption against preemption is important to the states and they contend that there should be no special exception for the OCC. The OCC staunchly contends that Congress intends it to be the sole regulator of national banks. Any state intrusion could result in conflicting requirements, enforcement poliCies, and expertise. This would be difficult and costly for national banks with nationwide operations, and the increased costs would fall on consumers. The agency argues that lending is a core banking activity authorized for national banks and only the OCC can address violations of state or federal law committed in the exercise of this basic banking function. Further, the OCC cites extensive case law deferring to the OCC. The OCC emphasizes that it does actively enforce state consumer protection laws and that it does cooperate \vith state regulators in doing so. Congress is also looking over the shoulders of the federal banking regulators and will be taking account of the Supreme Court's opinion in this case, regardless of the outcome. American Bar Association This case gives the Supreme Court an opportunity to answer questions left open in its 2007 opinion in Watters '0. Wachovia Bank. Because the Watters opinion relied on the National Bank Act itself, the Court did not directly answer questions concerning deference to a federal agency under the Oh€'Oron Doctrine. Administrative lawyers in every practice area, not just financial institutions, will be waiting with bated breath for whatever may come out of this case in terms of Ohevron deference analysis. The Watters decision was five to three, with a vigorous dissent, and Justice Thomas did not partiCipate. As a result, the tea leaves indicate that this case could go either way. ATTOlli~YS FOR THE PARTIES For Petitioner Andrew M. Cuomo, Attorney General of New York (Barbara D. Underwood (212) 4168016) For Respondent Clearing House Association, L.L.C. (Seth p. Waxman (202) 663-6000) For the Federal Respondent (Elena Kagan (202) 514-2217) AMIGGS BRIEFS In Support of Petitioner Andrew M. Cuomo, Attorney General of New York American Association of Residential Mortgage Regulators (Stefan L. Jouret (617) 951-2300) Center for Responsible Lending et aL (Eric Halperin (202) 3491850) Comptroller of the City of New York (Lewis S. Finkelman (212) 669-2048) Conference of State Bank Supervisors (DaVid T. Goldberg (212) 334-8813) Connecticut Fair Housing Center (Jonathan R. Macey (203) 4327913) 439 Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law et al. (Amy Howe (301) 941-1913) .Ylembers of Congress (Linda Singer (202) 778-1800) North American Securities Administrators ASSOCiation, Inc. (Keith R. Fisher (603) 513-5174) National Association of Realtors (David C. Frederick (202) 3267900) National Governors Association et al. (Richard Ruda (202) 4344850) ~orth Carolina et al. (Christopher G. Browning Jr. (919) 716-6900) In Support of Respondent Clearing House Association, L.L.C. All Former Comptrollers of the Currency since 1973 (Drew S. Days III (202) 887-1500) American Bankers Association et al. (Theodore B. Olson (202) 9558500) The Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America (Sri Srinivasan (202) 383-5300) Financial Services Roundtable (Robert A. Long Jr. (202) 662-5212)