Securing the Crime Scene 2

advertisement

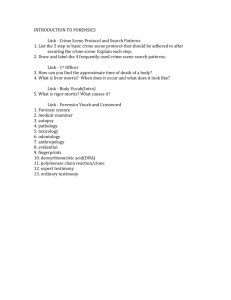

2 Securing the Crime Scene In an ideal world, crime scene investigators would be the first responders to all scenes, but in reality they are never that, and, for reasons of budget, may not even be called out to some incidents. A crime scene (CS) investigator will not be the first official at the crime scene, unless they happen to be the one who discovers the crime. Police will be called to the scene by the person reporting the incident, and are therefore responsible for the initial treatment of the area. A crime scene officer will be called out to the scene as a consequence of a decision by a police officer. It is important, however, for a CS officer to be aware of the protocols and responsibilities of the first response officer. 2.1 The role of the first response officer Some police forces describe the role with the acronym ARISN, which summarises the five key duties of the first officer on a crime scene: 1. Approach 2. 3. 4. Rendering first aid Identifying additional victims and potential witnesses Secure the crime scene Notify other appropriate authorities 5. There is a clear conflict in the need for the first response officer to help victims of the crime and prevent potential witnesses and suspects from leaving the area with the need to the avoid contaminating and damaging evidence at the scene. Minimising the problems associated with that conflict is something a police officer will gain with experience. Approach This refers to the time spent by the officer after getting the call to attend the incident. While it includes issues such as safe driving, from the crime scene investigator’s point of view, the most important aspect is the observations made by the officer as they approach the scene. Mark Hawthorne1 tells “of the many times I responded to a scene and found evidence altered or destroyed because it was lying in the street, and the officer who first responded to the scene ran over it with the patrol car because he or she was not looking for it”. Securing the scene and evidence It will be the first responder’s responsibility to ensure that the crime scene remains in a condition that allows later units (eg detectives, forensic officers) to do their work. If the evidence is disturbed before it is documented then it becomes nearly worthless, and certainly unlikely to be admissible in court (if the defence finds out!). To do this, he/she must actually identify the extent of the crime scene, which means carefully (to avoid treading all over it) identifying where the evidence is. For example, a burglar who cut himself on broken glass in a window may leave a trail of blood in the direction of escape. This expands the crime scene, and needs to be protected for further examination. There is obviously a limit to how far the crime scene can be expanded at this early stage, depending on the locality, the resources available and the time required to look. Later, secondary crime scenes may be established at separate locations. 1 Mark R Hawthorne, First Unit Responder, CRC Press, 1999, pg 12 2. Securing The Crime Scene EXERCISE 2.1 What is the crime scene secured against? CRIME SCENE– DO NOT CROSS The means by which the crime scene is secured will obviously depend on the size and nature of the crime scene. The way that we see on all police shows is the CRIME SCENE – DO NOT CROSS tape around the perimeter of the scene. EXERCISE 2.2 What other ways might there be to secure a crime scene? A crucial role of the first responder unit, and then their relief, is the establishment of a crime scene log. This documents who has entered the crime scene, when and when they left. Obviously, it is only authorised persons who will be allowed cross the secure boundary, but they must be recorded. EXERCISE 2.3 (a) Other than forensic officers and police, who else might be authorised to enter the scene? (b) Why is it necessary to record the arrival and exit of authorised persons onto the crime scene? (c) What information should be recorded on a crime scene log, other than the names of those who access the scene? Crime Scene Processing 2.2 2. Securing The Crime Scene EXERCISE 2.4 Read the following2, which describes the sequence of events in the “OJ Simpson” case from the initial report to the point at which forensic officers arrive. Underline the significant aspects of the account as they relate to the first response officers and the securing of the crime scene. Anything that appears incorrectly done should be indicated. The report The dog kept barking late on this foggy Sunday evening, June 12, 1994. Pablo Fenjves, a screenwriter, thought he heard it the first time at about 10:15. Elsie Tistaert, who lived just across the street, also heard it, and when she looked out of her window, she saw the dog, a white Akita, pacing up and down outside the front of 875 South Bundy Drive. Louis Kaupf, who lived next door to 875, returned late from the airport and went out to clear his mail at 10:50. The dog was still barking and trotting up and down in an agitated manner. Just before 11:00, Steven Schwab, who was walking his own dog, came across the distressed animal. It followed him home. There, he noticed that the dog's belly fur and paws were matted in red. Schwab asked his neighbour, Suka Boztepe, to care for the dog overnight. He agreed, but as the dog persisted in his restless behaviour, Boztepe and his partner, Bettina Rasmussen, decided to walk the dog and try and calm it down. The dog dragged them back to number 875, where it stopped and gazed down a dim, tree‐shaded pathway. Following the dog's stare, they saw a shape of someone lying at the foot of some steps, part of the body sprawled under an iron fence. First response At 12:13 a.m., the first LAPD black and white patrol car arrived on the scene in response to a call from Tistaert. In it were Officers Robert Riske and Miguel Terrazas. They went through the entranceway of the off‐white stucco, three‐level condominium and made their way cautiously up the pathway. Officer Riske was mainly concerned about not stepping in a small lake of blood as he proceeded up the tiled walkway where he reached the first body, which lay about 15 feet from the sidewalk. It was a woman, sprawled face down, left cheek pressing into the ground, her right leg jack‐ knifed under the gate frame to the left and her buttocks pressed up against the first riser of the four steps that led up to the path leading to the front door of the condominium. She was wearing a short black dress, drenched in the blood that had poured out of wounds to her upper body and throat. To her right, just beyond an agapanthus bush in a small garden enclave off the walkway, lay the body of a man. He was crumpled over on his right side, sprawled against a garden fence. His eyes were open and his light brown shirt and blue jeans were saturated in blood. After establishing that both victims were dead, Riske and Terrazas radioed for backup. Within minutes, Sergeant Martin Coon and officers Edward McGowan and Richard Walker arrived and went about securing the crime scene and controlling the traffic flow on South Bundy, which was busy even that early in the morning. At 12:45 a.m., paramedics from a nearby fire station arrived and confirmed that the man and woman lying in the grounds of the condominium were indeed very dead. By then, Riske and another patrol officer had established that the woman was probably Nicole Brown Simpson, the owner of the building and the ex‐wife of O.J. Simpson, the retired football player and sports newscaster. Upstairs in their bedrooms, they found her two young children, 9‐year‐old Sidney and 6‐year‐old Justin, fast asleep. The officers awakened them, got them dressed and arranged for them to be taken to the West Los Angeles Division to await formal identification by a family member. An animal control officer arrived and picked up the Akita, which was taken to a pound in West Los Angeles. At this point in time, the identity of the dead man had not been established. 2 Source: http://www.crimelibrary.com/notorious_murders/famous/simpson/brentwood_2.html Crime Scene Processing 2.3 2. Securing The Crime Scene Follow‐up At 2:10 a.m., West Los Angeles Division Homicide Detective Supervisor Ron Phillips, accompanied by Detective Mark Fuhrman, arrived at South Bundy and carried out a visual inspection of the area, without approaching the bodies or getting too close to the immediate crime scene. By then, Fuhrman's partner Brad Roberts had arrived, logging in at 2:30 a.m., on the sign‐in sheet set up by Officer Terrazas. He was the 18th police officer on the scene by this time. Division Head Captain William O. Gartland assigned Detectives Third Grade Tom Lange and Phil Vannatter as the lead investigators. They arrived at the crime scene and logged in at 4:05 and 4:25 a.m., respectively. By this time, no one other than the responding officers had come close to the bodies or the area of their containment. Phillips had summoned a police photographer who had arrived at 3:25 a.m., but his function was restricted to general area photographs because police department policy prohibited him taking shots of the bodies or evidence except under the supervision of a lead detective or a Special Investigation Division criminalist. These are civilian employees of the LAPD engaged in the scientific analysis of physical and chemical evidence materials. Their essential functions are to collect, test and analyse evidence such as drugs, blood, paint, glass, explosives, hair, clothing and other crime‐related materials. They are also expected to compile data, maintain records and reports, and present testimony in court as required. Detective Phillips briefed Vannatter and walked him through the crime scene. Without physically disturbing the bodies, which could only be done by a coroner's investigator, the two police officers could not be certain of the cause of death of the two victims. The two men never got closer than six feet to the two crumpled figures. They did however see a number of objects adjacent to the dead man. There was a set of keys, a dark blue knit cap, a beeper, a blood‐spattered white envelope and a bloodstained left hand leather glove lying under the agapanthus plant only a few inches from Nicole Brown's body. There seemed to be a trail of bloody footprints leading away from the bodies towards the back of the property and alongside these, drops of blood trailing in the same direction. EXERCISE 2.5 The continuing story of the burglary at the Jones house. This part deals with the actions of the first police officer on the scene, PC Brown and the handover to the CSI officer. The first police officer to arrive in response to such a phone call would be logged at the police Control Room as the ‘First Officer Attending’ or FOA. In this instance the FOA was PC 1153 Brown and an essential part of his job was to reassure the victim, Jane Jones, to check the house and to outline to her what has to happen next. At the same time, he was starting the process of the investigation by thinking through the burglar’s likely actions, asking himself such questions as ‘What did he do?’, ‘What evidence might he have left behind?’ and ‘Where might he be now?’. The FOA informed the Control Room that the burglar might still be in the area and that he would require scientific support. PC Brown asked Mrs Jones not to touch anything or to walk around whilst he assessed whether any evidence needed protecting. Clearly the intruder had stood on the dustbin lid which was outside and exposed to the weather; this PC Brown removed to the security of the garage. Then PC Brown and Mrs Jones entered the house through the front door, thus ensuring that they did not disturb any evidence in the kitchen. Leaving Jane Jones in the doorway, PC Brown quickly looked round the house to check that no intruder remained in the building and to make an initial assessment. He then walked round it again, this time more slowly and accompanied by Mrs Jones so that she could confirm what had happened whilst she was out and also what appeared to have been taken. They were both careful of where they walked and of what they touched. Crime Scene Processing 2.4 2. Securing The Crime Scene He gave clear instructions to Mrs Jones so that no potential evidence would be destroyed or compromised by her actions. He was aware of her wish to tidy her home and to make it secure and so offered practical advice about which parts of her home she could enter. Before he left, PC Brown also told her exactly what was going to happen in the next stage of the investigation. He obtained, via his personal radio, an estimate of the time a Scientific Support Officer might arrive and left for him a written note summarising his own thoughts and actions. PC Brown had now discharged his basic duties at a crime scene of assessing and controlling the situations, protecting the evidence from disturbance and contamination and communicating with those who would now take the enquiry forward. He then completed his required personal records of the incident. (a) What were PC Brown’s two key duties in attending this crime scene? (b) What were his first actions? (c) How did he go about assessing the interior of the house for evidence? (d) What instructions were provided to Mrs Jones during the course of PC Brown’s investigations? (e) How did PC Brown communicate with the crime scene officer regarding his assessment of the scene and his actions? What are your thoughts about this? Why do you believe it was done in this way? 2.2 Arrival of the crime scene officer The timing of the arrival of the crime scene investigating (CSI) officer or team will depend on the seriousness of the case and the fragility of important physical evidence. Of course, in many less serious cases where the attending police have assessed that there is little or no physical evidence, the CSI office will not even get a call. Their resources are stretched thinly in all police jurisdictions, so that priority must be given to serious crimes and to scenes where evidence is obvious. In cases of lower‐level crime (e.g. burglary), where the police have identified that valuable and useful physical evidence exists, the CSI officer’s arrival is likely to be when a window of opportunity arises in the work schedule. This could be the following day in some cases. Clearly, the police will have long since departed the scene, and the investigating officers will not meet the CSI at the scene at all. Communication between the two will be later when results are available. In serious cases (e.g. Crime Scene Processing 2.5 2. Securing The Crime Scene murder, rape), the call to the CSI team will go out almost immediately, and they will be there along with the first response police and probably detectives. Handover In many cases, especially the more serious ones, the arrival of the crime scene officer (and the detectives) marks the real start of the investigation. Up to that point, the first officer on the scene will have been carrying a holding operation at best. The officer on the scene will have had minimal opportunity to look at the physical evidence because of the risk of contaminating it (and it isn’t his/her job anyway), and access to witnesses and/or suspects may have been limited by the need to maintain a secure crime scene or render first aid or similar assistance. Regardless of the level of the case, the CSI officer should begin by consulting with the first response police officer, and obtaining as much information as possible about the crime scene. EXERCISE 2.6 (a) Why wouldn’t the CSI officer simply march onto the crime scene and begin work, without consulting with the first response officer? (b) What information can the first response officer provide to the just‐arrived crime scene officer? 2.3 The preliminary survey Armed with whatever information is available from the police officers attending the crime, the CSI officer can now proceed to do what he/she is paid for: investigate the physical evidence at the scene. However, it is not a matter of ploughing into the scene and picking up evidence randomly. It is likely that the officer will block off an area larger than the core crime scene because it's easier to decrease the size of a crime scene than to increase it – press vans and onlookers may be crunching through the area the CSI later determines is part of the crime scene. A "safe area" establish just beyond the crime scene where investigators can rest and discuss issues without worrying about destroying evidence. A plan of attack is necessary for an efficient and effective recovery of evidence and documentation of the crime scene. “What needs to be done first and by who?” and “What can be left until the end?” are some of the questions that can be answered by some planning at the start. If the crime is serious enough to warrant more than one CSI officer at the scene, then the senior officer will determine the sequence of actions, and carry out the preliminary survey. The survey will familiarise the officers with the layout of the crime scene, and will to help to identify important aspects of the scene beyond where the obvious pieces of evidence are. The key part of the survey is the walkthrough. This involves a cautious, relatively quick but comprehensive viewing of the crime scene. It will establish priorities for the full processing of the crime scene, and the documentation (written, photographic) establishes the condition of the scene as first observed. There is the problem of course with this initial process: how to avoid damaging evidence when you don’t know where it is? Experience, caution and following a path likely to contain the least amount of evidence. Crime Scene Processing 2.6 2. Securing The Crime Scene What can the walkthrough identify? whether the area needs to be expanded or reduced whether the scene may need to be separated into multiple smaller scenes location of physical evidence already found by the first response officer transient or fragile physical evidence which needs immediate action or protection OH&S issues the best means of entry and exit for authorised personnel the need for specialised personnel, extra equipment etc the need for special or extra equipment and evidence collection bags etc “wrong‐seeming” aspects of the scene EXERCISE 2.7 Give examples of the following identified in the walkthrough: transient or fragile physical evidence which needs immediate action or protection OH&S issues the need for specialised personnel, extra equipment etc the need for special or extra equipment and evidence collection bags etc “wrong‐seeming” aspects of the scene The walkthrough forms the start of the documentation process that is covered fully in the next chapter. What You Need To Be Able To Do define important terminology outline the roles of the first responding unit to a crime scene explain why a crime scene needs to be secured explain how the crime scene is secured outline the procedure for crime scene handover explain the purpose of the preliminary survey list what is done in the preliminary survey Crime Scene Processing 2.7