Law and Natural Rights: Montesquieu and Rousseau Dr John Snape,

advertisement

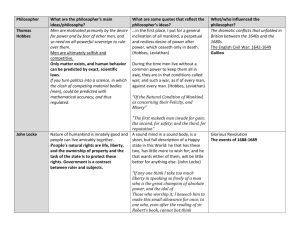

Law and Natural Rights: Montesquieu and Rousseau Dr John Snape, Associate Professor, School of Law Mme Geoffrin’s ‘Salon and Times’ (Darach Sanfey found this) The Questions • Since Ancient Greece, people have been obsessed by variants of one question - how can we best live together? • Their answers have always been about law – create laws that best promote values held dear (religious, ideological) • Pre-Enlightenment thought looks to God or gods • Enlightenment thought looks to mankind - preoccupied with how we discern those values - how can we create the laws that realise them? By a ‘science of politics,’ of ‘political law’, of ‘public law’, of a ‘science of legislation’ Two Sorts of Answer • One type of answer – ‘scientifically’ – what are men and women really like? What laws best address their true nature? – Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755) • Separation of Powers – ésprit général • Less all-embracing • Another type of answer – ‘speculatively’ – knowing what we know about people, how could laws be made legitimate? – Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) • General will – sovereignty of the people • More all-embracing Rousseau (1712-1778) Discourse: ‘Sur l’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité’ (Dijon, 1755) Du Contrat Social (Amsterdam, 1762) Émile, ou de l’éducation (Holland and France, 1762) Montesquieu (1689-1755) Lettres persanes (Anon, 1721) Réflexions sur la Monarchie universelle en Europe (1734) De l’ésprit des lois (Anon, Switzerland, 1748) Montesquieu and Rousseau (1) • Montesquieu deploys new version of natural law (sc ‘law of nature’) to state what laws best address true nature of men and women – Laws in general (he says) are ‘the necessary relations arising from the nature of things’ (EdL, I.i) • Rousseau largely rejects natural law in favour of the customs of people, all natural rights being surrendered on man’s entry into political order – Laws are “Nothing but the declaration of the general will” – Can there be ‘any reliable and legitimate rule … taking men as they are, and laws as they can be’? (CS, I) Montesquieu and Rousseau (2) • Backgrounds and mentalities of each man as different as possible to be in eighteenth century Europe • Montesquieu - a nobleman (de la robe) - a former judge, président à mortier (hence ‘President M’): a cautious, empirical, reasoner - privileged • Rousseau a ‘Citizen of Geneva’ – son of a philosophical clock-maker, learned in early-modern political thought – not at all privileged! • Views that each developed expressed this difference in backgrounds and outlooks – Montesquieu occluded – Rousseau strident and direct: ‘Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains’ (CS, I.i). Natural Law (1) • Each thinker engaged in different ways with the claims of natural law – the law of nature • For centuries, in the West, this had been defined by St Augustine (354-430CE) and by St Thomas Aquinas (c1225-1274CE) – about the soul and reaching heaven • Thinkers such as Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) and John Locke (1632-1704) had sought to redefine natural law – more about mankind, less about God • To the Lockeian mind, precepts of natural law had to be formulated by reference to empirical observation, not (mainly) the transcendence of the human soul – nonetheless, natural law ‘conservative’ (Courtney) Natural Law (2) • Even as reformulated, there are problems. Natural law – is deterministic (‘Whatever is, is right’ – Alexander Pope) – might imply there can never be real change • Montesquieu and Rousseau respond to these problems in different ways – Montesquieu by a (Lockeian) reformulation of natural law, in terms of climate and regimes • Esprit des lois (1748) – explanation of why positive laws as they are (building both on Grotius and Samuel von Pufendorf (1632-1694) – Rousseau by (largely) rejecting natural law and supplanting it with ‘public reason’ and societal customs, beliefs, morality • Du contrat social (1762) – argument for a better political society than the reality of European states Natural Rights • Men and women ‘born free’ and good, with ‘natural rights’ (‘inalienable rights’) - radical, not conservative • Issue is whether can reserve natural rights on entering political society –Yes, Montesquieu • No, Rousseau, Hobbes. Must all be surrendered to the state • Lying, cheating, killing, etc did not apply in the state of nature because no property (contra Hobbes, Montesquieu) – but ‘we should not expect anything different from the noblesse de robe’ (Loughlin, p 138, of Rousseau’s view) • When natural rights become civil rights, justice is substituted for instinct (or ‘pity’) in the state of nature – effect of politics is therefore ‘utterly transformative’ (Loughlin, p 345) Separation of Powers • Montesquieu – men are fearful - must be checks and balances in the state (see also Locke) – legislative and executive (plus judicial) – a matter of empirical observation – based on Montesquieu’s view of the English constitution (a commercial republic disguised as a monarchy) – English a people gripped by anxiety • Tyranny - the failure to use power for the public good – what Montesquieu really worried about is despotism, or government by fear – Rousseau – men should be free – necessary to separate will from force – legislative from executive and two make sure two operate together The General Will (1) • Rousseau, rather than Montesquieu – – – – We, the people, can decide what to do By a majority Directly, not through representatives By a size of majority according to nature of issue • Will = sovereignty – Not about a sovereign – Not, as such, about the state – About the surrender of individual rights to the general will • Not natural right but political right The General Will (2) • Rather than the general will, Montesquieu has ‘the general spirit’ (l’esprit général), consisting of seven causes, all balanced, all requiring the attention both of legislator and historian: – – – – – – – climate (the only physical cause); religion; laws; ‘maxims of government’; past examples; customs; and manners Liberty • For Montesquieu, about security, especially of property – ‘Freedom from fear’ – Rule of law – Not about surrender of natural rights to general will • Rousseau – about being free within political order – an exchange of natural freedom for political freedom – obedience to selfprescribed law – civil freedom unlike natural freedom constrained by general will (see Loughlin, pp 113-5): ‘if anyone refuses to obey the general will he will be compelled to do so by the whole body; which means nothing else than that he will be forced to be free’ (CS I, vi) • ‘State of Nature’ v Political order – inequality of state of nature ‘institutionalized’ in political order (Brooks) • Only a lawgiver is wise enough to found a political order ‘Influence’ and Reception • In France – Montesquieu – read by Rousseau, by later philosophers and by French revolutionaries of 1789-1799 – Rousseau – likewise as regards revolutionaries - Robespierre (17581794) an avid early reader (as too of Montesquieu) • In England – Montesquieu – very popular among elite, even ‘fashionable’ (Langford) – Edmund Burke (1729-97) a great admirer – Rousseau – popular with Radicals – eg Thomas Paine (1737-1809) – but conservative Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) thought he was a ‘bad man’, along with Rousseau’s (one-time) friend David Hume (17111776) • In America – Montesquieu key to framers of US Constitution – Federalist Papers (Hamilton, Madison) Rousseau on Montesquieu • Rousseau in Émile: ‘The science of politics is and probably always will be unknown. […] In modern times the only man who could have created this vast and useless science was the illustrious Montesquieu. But he was not concerned with the principles of political law; he was content to deal with the positive laws of settled governments; and nothing could be more different than these two branches of study.’ (E, pp 421-2) • But Rousseau like Montesquieu in some ways – both think custom important – both think such a concept as natural right • Whether two men met ‘quite likely’ but not certain – Rousseau report’s Diderot’s presence at Montesquieu’s funeral in Paris (Shackleton, p 37) – personal knowledge? Concluding Thoughts (1) • Difference of perspective between Montesquieu and Rousseau: – Empirical (Montesquieu) – ‘sociology’ of positive laws – Idealistic (Rousseau) – about deliberative political philosophy – ‘What’s the right thing to do’? (Sandel) • History and nature – Montesquieu cautious about history but nature rethought – History an aspect of the general will for Rousseau • Moderate and radical – Moderate (Montesquieu) – Radical (Rousseau) – Robespierre, above Concluding Thoughts (2) • Montesquieu – Influential early on in economics and commerce (see Céline Spector’s work) – Implies small government – Regarded as great liberal thinker • Rousseau – About politics, ethics, deliberation – Suggests idea of big government – At best an ambiguous liberal – libertarians hate him! • Neither Montesquieu or Rousseau atheists – both still have some idea of God – envisage, though, a distinct place for the Deity in human affairs Some Further Reading • Rousseau, Social Contract (CS), Book I; Émile, esp Bk V (‘Of Travel’); Montesquieu, Spirit of Laws, Bks I, VI and Bk XIX, chs 4, 27 • Secondary: Martin Loughlin, Foundations of Public Law (Oxford, 2010) pp 112-9, 137-9, 343-6; R Wokler, Rousseau: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2001); N Dent, Rousseau (Abingdon, 2005); L Damrosch, Jean-Jacques RousseauRestless Genius (New York, 2005); R Shackleton, Montesquieu, A Critical Biography (Oxford, 1961); C Courtney, Montesquieu and Burke (Oxford, 1963)C Spector, ‘Honor, Interest, Virtue: The Affective Foundations of the Political in The Spirit of Laws’ in Montesquieu and his Legacy (RE Kingston (ed)) (Albany, 2009); T Brooks, ‘Introduction’ in Rousseau and Law (Aldershot, 2005)