Document 12787382

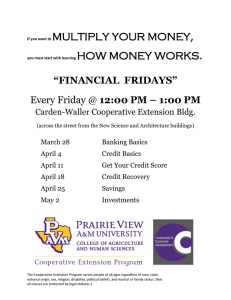

advertisement

High-Resolution Mapping of Inherent Growth Variation 1n Coastal Douglas-Fir Roy R. S11en.!./

Six high-resolution maps of genetic height variation for small breeding zones

in western Oregon are presented in this paper. Production of such maps is

becoming routine. Two maps were presented 1n the April 1983 issue of the

Journal of Forestry (Silen and Mandel 1983). Since then four more have been

produced as part of an analysis package as 5-, 10-, or 15-year data are

processed for progeny tests of breeding zones for the Progressive Tree

Improvement Program (Silen and Wheat 1980). Full or partial data on 26 more

breeding zones in Washington and Oregon are scheduled for analysis in 1984.

Within a reasonably short period, the 1. 3 million acres now mapped may expand

to over 3 million acres. Total height, or incremental height, is the only

genetic trait now routinely mapped. My purpose is to display the maps,

describe the data base and analysis, briefly discuss computer processing and

enhancement, and highlight patterns of geographic genetic variation co1111o

1 n to

the six maps. Implications for genetic programs are not covered.

Coverage

Figure 1 shows 8. 2 million acres in western Washington and Oregon in the

Progressive Tree Improvement Program. There are 90 breeding zones of 100,000

to 300,000 acres. Within zones, the sampling of parent trees 1s fairly

dense--usually two trees per square mile of forest ownership. For these six

maps the number of parent trees ranges from 161 to 900. In other words, there

are a lot of sample points per map. Parents are evaluated at 5-year intervals

from metric height measurements of progeny on 6 to 12 sites, each with 12 to

20 progeny. With over 100 progeny per parent the family mean is a fairly

precise statistical estimate of performance. This large number of individuals

per family probably accounts for the clarity with which patterns of geographic

genetic variation often appear when unprocessed family means are plotted on a

map. Sometimes the patterns are improved by computer enhancements, and

sometimes not.

Highlighted on the figure are five presently mapped Douglas-fir cooperative

program areas--Vernonia, Molalla, Burnt Woods, Gold Beach, and Dallas. The

sixth map applies to a program in western hemlock--the Tillamook Hemlock Tree

Improvement Program.

Vernonia Tree Improvement Cooperative

Figure 2 shows a 350,000-acre forest area directly west of Portland, Oregon,

of this Cooperative mainly owned by Crown Zellerbach Corporation, Longview

Fibre Corporation, International Paper Corporation, and the State of Oregon,

known as the Vernonia Tree Improvement Cooperative. The basic procedure for

constructing the genetic maps is to plot the family mean height at its

coordinate location, then draw in isoheight contour lines. The Vernonia map,

the first such map, was prepared by hand. With 900 parent trees to be plotted

.!./The

Author--Roy R. Silen, is genetics project leader, Forestry Sciences

Laboratory, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, USDA Forest

Service, Corvallis, Oregon 97331.

581

and with decisions needed about map scales and background information such as

topographic contours, rivers, roads, and towns, the several trials of various

alternatives proved to be tedious. For the map shown, we used the height

growth increment from years 7 to 10 as the plotted variable, mainly to

eliminate the large variation in heights in the first 7 years caused by

animals, brush competition, and frost.

Without applying any computer enhancement techniques, the basic data itself

provides clear geographic patterns. Note that in the hilly area south of the

Nehalem River, nearly all family height growth over 200 cm can be included in

a 1- to 6-mile-wide band on the rolling ridgetop, at 1,200-1,500-feet

elevation, and that two parallel bands 1- to 6-miles wide downslope include

the 190-199 cm, and then the 180- to 189-cm trees in this valley bottom. On

this gentle, 10-mile slope there is a genetic cline from the Nehalem River

bottom to the ridgetop. Note the similar band of 200+ cm growth on the ridge

that parallels the Columbia River north of the Nehalem River. The parentage

at the western edge of the Willamette Valley and in the lowlands northward to

Vernonia are relatively slower growing. A most striking feature concerns the

70 families on the south end of the map located at 1,500- to 2,400-feet

·elevation on the southeast flank of Saddle Mountain, all with below average

growths of 178 to 190 cm.

Computer Aids

All this former handwork, except drawing of the 1soheight lines, is now done

by computer. Cooperators are asked for coordinates of parent tree using the

military grid found on all U. S. Geological Survey (USGS) Quadrangle sheets.

The metric grid on USGS maps is shown in 10,000-meter marginal tic marks. The

0,0 origin is somewhere in the Pacific Ocean to assure that all coordinates

are positive. The 10,000-meter grid (6.2 x 6.2 miles) will be prominent on

most subsequent maps. Up to 900 points were impossible to plot on a map of

useful scale, so the number of points was reduced by plotting the mean of all

families with parents in a 500-meter squilre. The density of points also made

necessary the coding of heights into classes represented by -single-digits.

Typically the range of heights is divided into five to ten classes represented

by the digits O through 9.

Computer maps are plotted on a 1:250,000 scale to correspond with a convenient

USGS map series. The coded values and a coordinate grid are plotted directly

on acetate sheets so that they can be overlaid on the USGS contour maps. The

isoheight lines are drawn on Xerox copies of the map plus overlay.

As

with the processing of satellite data, systematic and random variation can

sometimes be reduced by computer techniques. Krieging, a procedure that uses

a moving average, sometimes helps in smoothing out statistical variation. The

main statistical smoothing and data strengthening has been done with multiple

regression to predict an expected family height at the parents latitude,

longitude, and elevation. The method is described in a previous paper (Silen

and Mandel 1983). The method produces a response surface for which isoheight

contours are mapped.

Maps from Multiple Regression

The next map of the Vernonia area (figure 3) is based on parent tree values

estimated by multiple regression for their coordinate location. T this data

set there were significant effects of latitude and elevation squareo. The

582 response-surface map shows that parents in the north half would be expected to

perfonn better than average. The better perfonnance on the hills south of the

Nehalem River is also shown, as well as the poor performance of those

southeast of Saddle Mountain. The map becomes somewhat absurd in its

prediction that trees from the northeast corner should be 7-1/2 percent better

than average--a case of carrying trends too far.

The next map (figure 4) generated from 111Ultiple regression techniques applies

to the Molalla Cooperative. This cooperative of four landowners is located

southeast of Portland in the foothills of the Cascade Range and east of the

Willamette Valley. The forests range from about 1,000 feet to 2,600 feet.

The 375 selected parent trees are not well distributed and only about

40 percent of the mapped area is owned by the four landowners. But the data

is generally excellent and a number of factors were significant in multiple

regression analysis (latitude squared, latitude times elevation, elevation

squared, longitude times elevation, and longitude squared). The result was a

response surface of considerable complexity that fit the basic data reasonably

well.

The map shows a strong trend of better parent perfonnance to the north.

Parallel bands representing a change of 2-1/2 percent in total height at

10 years are spaced at 2- to 5-mile intervals. Best perfonnance in the north

is at 1,000 feet along the edge of the Willamette Valley. Performance drops

off upslope to about 1,800 feet, then improves again at elevations up to

2,500 feet. At the south end of the map the poorest perfonnance is from

parentage on the valley edge. Perfonnance there rises as parent elevation

increases. This is quite a complex geographic pattern. A feature of the

Molalla Cooperative data is that the top 10 of the 375 parent trees originate

in a 1- by 2-mile rectangle at 1,000 feet elevation near Colton, Oregon.

Burnt Woods Cooperative

The remaining four maps were constructed from basic data. No attempt has been

made at computer enhancements because newer data will soon become available

from 10- or 15-year measurements.

The Burnt Woods Cooperative (figure 5) tested only 161 parent trees on

70,000 acres owned by the State of Oregon and Starker Forests. The lands lie

west of Corvallis in an east-west oriented pair of drainages with flanking

highlands to north and south. Several points about the isoheight contouring

are of interest.

As with the Molalla Cooperative map, the top-perfonning parentage is confined

to a small area. One such area is south of Blodgett at 1,200 feet elevation.

Other areas of good parentage are associated with coves near the top of low

hills in the main drainages. At the northeast corner is a major ridge. A

clinal banding of the successively poorer growing parents occurs on the east

side of this ridge that forms the forest edge of the Willamette Valley, a

similar pattern to the Vernonia Cooperative map. The isoheight lines are

mainly oriented east to west paralleling the drainage pattern.

Gold Beach Cooperative

Several features seen in maps from the Gold Beach Cooperative (figures 6-8)

are unusual. The area is located astride the Oregon-California border and

583 includes a 15-mile-wide strip along 50 miles of the Pacific coastline. Two

major drainages are included--the Rogue River at the north and the Chetco

River at the south of the mapped area. The nine landowners in the Gold Beach

Cooperative own about 80 percent of the forest land. Sampling of

1,066 parents is more uniform than for any other of the six maps. This is

shown in figure 6 in which the coded values in each sampled 500-meter square

range from 2 to 6 with 4 the average value.

An enlargement of the Oregon-California border area is next shown with

isoheight lines (figure 7). The pattern of these lines is complex, but some

simplifications become obvious. The "average-growth" parentage along the

coast grades inland into "above-average" parentage, and then into islands of

"top" parentage, finally grading eastward into "average" and "below-average"

parentage.

Figure 8 covers the pattern for the 50-mile stretch of coastline. There is a

5- to 15-mile-wide band of average parentage (slant shading) that parallels

the coastline. The eastern edge of the sampled area has below-average

arentage (vertical shading). Each of the two major drainages has a basically

simple pattern. The east-west orientation of the Rogue River is characterized

by slow-growing parentage at the river mouth, then relatively fast-growing

parentage (heavy shading) for about 15 miles upstream in the valley bottom.

On either side of this faster growing band is a 1- to 4-mile-wide band of

average-growth parentage, and still more distant from the river is a band of

slow-growing pa entage. This pattern is like that for the east-west drainage

in the Burnt Woods Cooperative map. The Chetco River, with north-south

orientation, has the same banding pattern except that the valley bottom has

slow-growing parentage banded by average, then slow-growing parentage to the

west and fast-growing parentage to the east and south.

The most interesting feature has to do with location of the fastest growing

parentage. Other than an area of such parentage described for the Rogue

River, nearly all such parentage occurs either near the Oregon- California

border, or on a ridge paralleling the ocean north of the Rogue River. Note

how the small areas of best growing parentage ·are within island-like isoheight

contours of better than average parentage. Of these two areas, the one nearer

the Oregon-California border is interesting because it delineates nearly all

the extension of the range of coast redwood into southern Oregon. An

ecologist from the Siskiyou National Forest, USDA Forest Service, has

suggested that the coastal strip of average parentage corresponds to the

narrow range of western redcedar along the southern Oregon Coast. Figure 9

shows the isoheight lines drawn on a 1:250,000-scale USGS map of the type sent

to each Cooperator.

Dallas Tree Improvement Cooperative

This cooperative (figure 10) of seven landowners is located south of the

Vernonia Cooperative and west of Salem, Oregon. It fringes the Willamette

Valley for about 40 miles.

About 300 parent trees at elevations below

1,500 feet provide the data base. Only about 35 percent of the land area is

sampled leaving large gaps with no parent tree sampling.

Even so, the pattern is consistently one of increasingly slower growing

parentage as sampling approaches the edge of the Willamette Valley. We see an

isoheight line following the forest edge that includes all the below-average

584

parentage. The band of average parentage is 3- to 6-miles wide, with better

growing parentage generally westward. This is the similar pattern as reported

for the Vernonia and Burnt Woods Cooperatives. With so much of the forest

area unsampled, a lot of the isoheight lines are shown as dashes between solid

lines where sampling occurred.

Tillamook Hemlock Tree Improvement Cooperative

A cooperative involving five landowners of western hemlock forests along the

north coast of Oregon (figure 11) provides 5-year data for the last map. The

coastal strip samp'led with 300 trees varies from O to about 12 miles in width

along 70 miles of coastline. The pattern seems quite clear: Virtually all

parentage of below average performance can be delineated with a band

paralleling the coastline extending into each estuary about to the limit of

tidewater. Inland from this tidewater line are parent trees of average

performance. At intervals along the coast are island-like isoheight lines

that delineate the above-average parentage. Most of these islands of faster

growing parentage involve upland basins, ridges, and south-facing slopes

somewhat back from the coastline.

Discussion

There are some features in common to all six maps that support the concept of

a highly precise adaptation to local environments (Silen 1982):

1. Clinal variation is the rule. There are clear examples of gradual

changes of inherent growth along gradients of moisture or ¢emperature.

2. Fastest or slowest inherent growth rates are geographically localized.

There are clear examples in each of the six cooperative areas.

3. The correspondence of genetic isoheight lines with topographic features

is clear in many cases, and best where sampling of locales is dense.

Prime examples are the gradient of lesser growth toward the timber edge

of the Willamette Valley, the tidal relationship of slower growth in the

western hemlock area, the cline associated with the slope of the

Cascades, the band of similar performance along the 50 miles of coastline

near the Oregon-California border, and the faster growing parentage

associated with the redwood area in Curry County.

4. The north-south orientation of many isoheight bands follows predictions

from general regional studies. East-west valleys of the Burnt Woods and

Gold Beach cooperatives, however, demonstrate the overriding effects of

local topography.

5. All six cooperative maps display a 10- to 15-percent difference in

progeny height associated with geography. How much of this genetic

variation is applicable to use for upgrading growth in the area of poorer

growth on each map is a major question.

There is ready acceptance by geneticists of stable racial differences in

growth rate occurring along major latitudinal or elevational transects where

pollen exchange is unlikely. Here is added evidence that clinal variation is

maintaineo over distances so short that pollen exchange must occur. Any of

585 the six cooperative areas have as great or greater environmental variation as

might occur over whole states in the eastern United States. Obviously the

species would benefit from a similar precise genetic and environmental matchup

as occurs along the major environmental gradients. It would appear that such

a matchup is occurring even though the mechanism isn't understood.

Most Ranger Districts in the Pacific Northwest will soon have high-resolution

maps of inherent growth variation.

Literature Cited

Silen, R. R. Nitrogen, corn, and forest genetics. The agricultural yield

strategy--implications for Douglas-fir management. Gen. Tech. Rept.

PNW 137. USDA Forest Service, Pacific· Northwest Forest and Range Experiment

Station, Portland, Oregon 20 p; 1982.

Silen, R. R.; Mandel, N. L. Clinal genetic growth variation within two

Douglas-fir breeding zones. Journal of Forestry. 81:216-220; 1983.

Silen, R. R.; Wheat, J. G. Progressive Tree Improvement Program in coastal

Douglas-fir. Journal of Forestry. 77:78-83; 1979.

r

586 MSMllllGTON

COOP

...OGll.Uot S

··-

......

•I D t 0 I

...

I

-

.. , .,.....

Figure 1. --Twenty-three tree improvement cooperatives are outlfned fn western

Oregon and Washington, fnvolving 8.2 million acres and 44 landownfng

organizations. .Cooperatives for which maps of genetic varfation are presented

are shaded. Progeny test data from 161 to 1,066 parent trees were used to

prepare the six maps.

587

I'"· .......

,,,

'· .

'

L- '' 'i

.....- .:

.:··-- ::

'

,

I

"''"··· ·

Figure 2. --Vernonia Cooperative in the Coast Ranges west of Portland involved

900 parent trees tested on 12 sites by four landowners. This was the first

map attempted, so was prepared by hand methods. Decreasing progeny heights in

a cline from the hills of the Coast Range to the edge of the Willamette Valley

is a prominent feature of the map. Figures are centimeters of incremental

growth from 7 to 10 years.

588

}[

•

!

·'

•i

,,

,,

'I

i11

L

:1It

:1

ii ii!J I

i

:I

Q,···

.

\:j°;1:;C 'L' •JB82

i1•"1tOl PHfr

7""4 1C'r'1.Ni'51N:.Jll'

fs• Pllr'CTtP

Ml

"" '""

L•Rliio(\I""

E•o:trri'911""

--

·I.

AT ll 11N!'S

IT'JP(

(llllO.rrMl'l UR: '

""A" 9'(#. Ml;./n.R"f ....::;

T'ICll••rrt1'"

Figure 3.--Yernonia Cooperative map was prepared from 7- to 10-year

incremental growth predicted for each parent location by the regression

equation shown in the box below the map. The equation reduces statistical

variation, thus smoothing the data of the previous map which shows the

unprocessed data.

589

11 -

--

}{

•

•

r, 6BJ.Jo.. L•

•

-+2JO•

-

s ;s-1:r' 1.E.

E1+ 4.olO·J ·•:ir

- 2 32•Ill"' P'566

Figure 4.--Molalla Cooperative is in the foothills of the Cascade Range

southeast of Portland. Progeny from 375 parents were tested on nine sites.

The 10-year total heights produced the multiple regression equation in the box

below the map. The equation was used to estimate heights at parent

coordinates. Note that northern parents show superior heights. Clinal

variation is displayed up the slope of the foothills.

590

Mlf P

OF

CENEr"IC V,,,e1ATION

'·· ·

.S,.,0.,....,1: 0 .S-10 YrAR

f:ll.OwTM 'NClll,..,£NT

8v11Nr WOODS CooP£11tAT1>'£

/

..·

I!

,,.,,,,,, ' i�

1! :

·- \.-:.

...

i:

· .

I!

·

'-··

I!

II Ii

···

,,

1,'i

'i

1!!1 "

ii

-

- ..,..,

lj'

i

I,

I•

I'

'

'

!

!

--.....

'\.

'.

o

s ..

o

a '----'----J

,:

M I t.., E !I

Figure 5.--Burnt Woods Cooperative in the hills of the Coast Range west of

Corvallis displays coded 5- to 10-year progeny height in 10-cm increments

based on 161 parents tested on eight sites (1•260 cm; 7•320 cm). Drainage

orientation and isoheight lines are mainly east-west. Note concentrations of

fastest growing families south of Blodgett and steep clinal variation in

northeast corner associated with the rain shadow created by Little Grass

Mountain.

591

f

Figure 6.--Gold Beach Coo erative along the Oregon and California Coasts

embraces acreage of nine andowners with 1,0

. 66 tested trees. The better

distribution of parents is shown by the coded progeny heights. Note the

east-west alignment of the Rogue Rfver and northeast-southwest alignment of

the Chetco River for details explained in the text.

592

/ A

: 'I

. .

/

/

l•t()Q·ft#-·

• •/10· II• •

,

1 11-1••

.

•

(•)

,.,,_,,..

_,

v

..

Figure 7.--An enlargement of figure 6 in the area of the Oregon-California

border. Isoheight lines delineate locations of above-average (4'sl and

top-performing (S's) parent trees. Average parentage are fn a 3- to 6-mfle

coastal band, with top-performing parentage fnside islands of above-average

percentage.

593

•7200

C7100

.

•1000

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.-.

•

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

'6700

0

I

I

10

20

MILES

Figure 8.--Gold Beach Cooperative. Mapping for about 50 miles of coastline

forests displays the band of average-growth parentage along the coast, a

contrasting pattern for the Chetco and Rogue valleys, and islands of

above-average parentage near the California border and on a ridge north of the

Rogue River.

594

..

\ t+-,_

-- f

:,

-

_.. .

c_...,.,.;..

-- ·

,

- r-:::

S·YEAll.HTJ.

I• 1-.a•­

•• ••

4•1

I

.s.. i. ,.

J•

)

TI

;;::

.+--...-t-:-�"""!""'!'6il

I

, : .... a.•1.•

Figure 9.--All cooperative members receive more detailed maps of the kind in

this figure. Coded parental infoMnation and isoheight contours are drawn on a

USGS 1:250,000-scale topographic map.

595

•

I

I

i

••

:

50200

0

low

5

_,

10

I

I

I

\

MILES c

--

.

:· .. ..··

. .

-,

.

'

\

--

I

..

.

I, /

.

I

...

..

-.

'

..

50100

•

lfi:

.

..

.

.··

McMinnville

I

.·

Figure 10. --Dallas Valley Cooperative. The map, like that of the Vernonia

Cooperative area, displays a banding of below-average parentage fringing the

Willamette Valley. Successive bands of average growth and above-average

growth are indicated westward into the Coast Ranges.

596

Columbia River

�-..,,,,..""""'--- ,.,

- .____...,..

'

--8%

I

'

......

-

,, I ""'L

...,

I:/

I

I

I

,..._,

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

\,_,...,

c

I

,--+1%

L..

I

'"I

w

I

I

,I

,.-...

, ___ _

.

I ''

•,.:;.e.

....

Tiiiamook

­

+1%

- +1%

I ,-- \ ._. ___ _

S.Y:

,_

'

iw'"1

...,,

I

I

DI --0

,..-,. t,,:--+r.-

'-;'+a•;.

''I

IV

I

,_ .... , I

,...J ,,.,

,,,,-;

,,

I ,,

I

'..'l,

... \' _,,.

,, ..._,

"' ....."'

. ol

·

, ... ,

,

..... , ...,

,

I ,._,,

I "

I ­

I \';

Ao

Jiii '

!

l

-+ ...-

....

.

_.,,

0

5

10

,___...._

.__

_,

MILES

Figure 11.--Tillamook Hemlock Cooperative. Below-average parentage can be

delineated by a line along the coast into each estuary to about the limit of

tidewater. Average-growth parentage is found inland of this line. Several

scattered island-like areas of parentage with above-average growth occur in

basins, south slopes, and ridges somewhat back from the coast.

597