t.r§ Douglas-fir- Western Hemlock Society of l\tleF.n�i'rP Rs t I'I:3

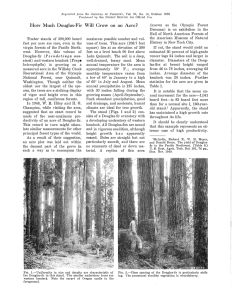

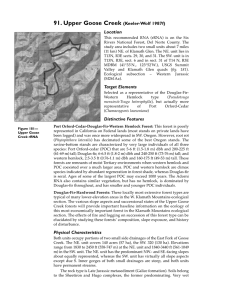

advertisement

FOREST COVER TYPES OF. THE UNITE t.r§ ATES AND CANADA Douglas-fir- Western Hemlock Society of l\tleF.n�i'rP ditor 230 Definition and composition. -Coast Douglas-fir and western hemlock are both present in substantial amounts in this mixed-species type , and together comprise at least 80 percent of the stocking. Douglas-fir usually is predominant (especially on drier sites), but hemlock may be so on more moist or less fertile sites. The most common associated conifer is western redcedar. Grand fir, western white pine, and Pacif­ ic silver fir are also quite often associated. Sitka spruce is frequently present at low elevations and noble fir is sometimes present at elevations above 000 m (2,000 ft.) in the Oregon and Washington Cascades.' Lodgepole pine may be an associate on drier sites. Western (Pacific) yew is often present, but always in a su rdinate position. Several hard­ wood species may be present in small quantities. These include red alder, bigleaf maple, black cot­ tonwood, giant chinkapin, Pacific madrone, vine maple, and cascara buckthorn. Geographic distribution.- The Douglas-fir­ western hemlock type occurs west of the Cascade Range from Vancouver Island and the British Co­ lumbia coast southward through western Washing­ ton and western Oregon. The northern limit is around Bella Coola (52° north· latitude). In Oregon the type is split into two major segments-Coast Ranges and Cascades. The southern limits, except for a narrow coastal strip that extends into northern California· (41 ° north latitude), are the Klamath Mountains on the coast and the divide between the North and South Umpqua rivers in the .Cascades. The type may be found at elevations ranging from sea level to about 1,100 m (3,600 ft.) (Franklin and. Dyrness 1973). Ecological relationships. - This cover type falls mostly within the Tsuga heterophylla forest zone defined by Franklin and Dyrness (1973). It also extends into their Picea sitchensis and Abies amabilis zones. These three forest zones are essentially anal­ ogous to Krajina's (1965) coastal western hemlock and wet subzone of the Douglas-fir biogeoclimatic zones to which the type is limited in British Colum­ bia (Packee 1976). The area occupied by this . als.o loosely corresponds with Mernam,s humid transition life zone as defined by Scott (Barrett . 1962). . This type thrives in mild, humid climates. Mean annual precipitation ranges from about 1,200 to 4,000 mm (50 to 16.0 in.); it may be as much as 6 000 mm (235 in.} at some places in the north. Commonly less than 10 percent of the precipitation falls during the summer. At lower elevations there is very little snow whereas at higher elevations snow­ fall may avera e more than 2 m (7ft.}. Within the major part of the type's range, mean annual tem­ perature is 7° 'to 10° C. Neither winter nor summer temperatures are extreme. Soils are derived from a variety of parent materials, but most are at least moderately deep and of medium acidity. Surf ce horizons are well aggregated and porous, With moderate to high organ,ic content (Franklin and J)yrness 1973). · · g Rs t I'I:3 F. H. Fyre, 1980 ·Stands of this type can be either mid-phases in the natural succession from seral Douglas-fir to clim ax hemlock- western redcedar (or hemlock), or even­ aged forest that became established after fire or other disturbance. At advanced ages, the Dougl as­ fir usually dies out and is replaced by more shade tolerant species, but on many drier sites the type persists. Douglas-fir is a long-lived species, and ages in excess of 500 years are not uncommon. Both Douglas-fir and western hemlock succumb to crow n . fires. but the thick bark of older Douglas-fir res ists surface fires (Fowells 1965). A new understory of hemlock, western redcedar, and true firs often be­ comes established under the survivin g old-growth. Douglas-fir. These understory species require a moist site for proper development. Following denudation by fire or logging, dense, nearly pure, even-aged stands of Douglas-fir com­ monly develop on areas previously occupied by the Douglas-fir-western hemlock type. This conver­ sion to pure Douglas-fir is now being further en­ couraged by extensive planting of Douglas-fir after logging. Hemlock, however, ofte n seeds in at about the same time and thus tends to recreate the mixed type Sometimes these hemlocks beco me a substan­ tial component of the main canopy . At other times particularly where they ar(i stres sed by high tern: perature or low soil moist\ll'e, hem locks, although numerous, remain in the understo ry (Packee 1976). Variants and associated vegetatio n. -There are many variations, involving both the relative impor­ tance of the two component spec ies of the type and associated tree and understory species. For ex­ m:ple, there is a rather regular incr ease in Douglas­ frr Importance from north to sou th in response to decreasing moisture (Franklin and Dyrness 1973). This type may merge with several other types, in­ cluding the Pacific Douglas-fir type on the drier sites and the western redcedar-w estern hemlock type the wetter sites. At these transitions it may . be diffiCult to assig n type names with accuracy . Within other types, Douglas-fir and western hem'lock often occur together, but generally they are overshadowed by other species. Shrubs commonly associated with the type in­ clude salal, Oregongrape, red huckleberry, 0\·alleaf huckleberry, salmonberry, thimbleberry, devils­ club,and rhododendron. Ass ociated herbaceous species include swordfern, dee r fern twinflower ' ' and Oregon oxalis. . · · DoNALD L. BEuKEMA USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station