Document 12756729

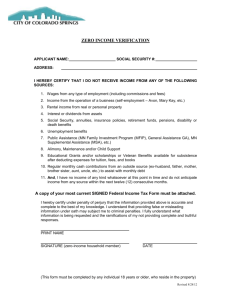

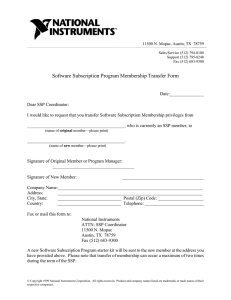

advertisement