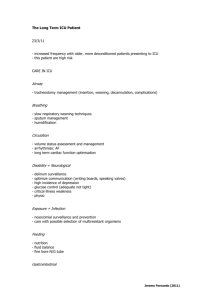

Protocol

advertisement