RESE ARCH The Emergence of Culture-led Regeneration: A policy concept

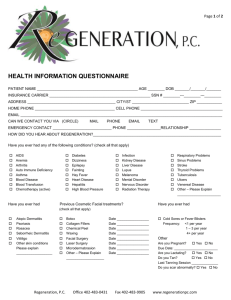

advertisement