Document 12580293

advertisement

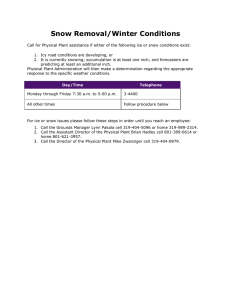

INCREASED WINTER-­‐SEASON SNOWPACK ABLATION FOLLOWING SEVERE FOREST DISTURBANCE: IMPLICATIONS FOR NEGATIVE FEEDBACKS ON WATER AVALIABILITY 1,2 2 2 3 Adrian Harpold , Paul Brooks , Joel Biederman , and David Gochis 1Ins$tute for Ar$c and Alpine Research, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, 2 University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, 3Na$onal Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO Background and Field Sites • Severe forest disturbance due to fire, insects, and drought is increasing in the Western US • We summarize the results of two studies inves?ga?ng winter-­‐season snowpack processes in the Rocky Mountain (Fig. 1) at three field sites: Chimney Park (tree morality from Mountain Pine Beetle (MPB) is >60%), Niwot Ridge (healthy control site), and Valles Caldera (100% tree mortality at Post-­‐burn site, 0% at Unburned site). Healthy Unburned MPB-effected Post-burn Competing Hypotheses for Snowpack Processes Following Disturbance 1. Reduced interception and sublimation from the canopy results in greater inputs to the snowpack (a) 2. Increased winter-season ablation from the snowpack surface results in reduced peak accumulation Snow depth (m) 0.3 Results and Discussion New Snow Accumulation Increases Following Disturbance Fig. 2 • Healthy forests intercept roughly 20-40% of incoming snowfall (Fig. 2 following MPB and 3 following fire). • Interception by grey phase trees is near zero (Fig. 2). • A single storm produces significantly more new snow in a post-burn area (Fig. 3b) than a healthy forest (Fig. 3a). 0.2 Mean = 0.143 m 0.2 x x a a,b 0.1 0.1 x b,c a,b Fig. 3 0.0 0.0 Open Snow depth (m) Fig. 1(b) 0.3 x Open Sparse Medium Dense (a) Mean = 0.512 m 0.9 b x x y c 0.3 0.3 0.0 0.0 Open Sparse Medium Dense y Sparse Medium Dense Fig. 4 140 (b) Mean = 0.456 m 0.6 b Sparse Medium Dense 0.9 a 0.6 Open Changes in Peak Snow Distribution Following Disturbance Fig. 5 a. 110 80 50 0.4 New snow accumulation 3/11 and 3/12/2012 b. 110 110 80 -80 -60 -40 -20 0 20 Position on Transect [m] 40 Declines in Peak Snow Following Disturbance 60 80 100 0.1 Fig. 6 None Sparse Medium Dense • There is no statistical difference in the SWE to P ratio (SWE:P), or the amount of SWE at max accumulation relative to total precipitation, in green, red, and grey MPB-effected areas (Fig. 6). • The SWE:P ratio declined relative to pre-burn snowpacks and suggested 10% greater losses than an Unburned area (Fig. 7). 0.75 a. 0.0 α 4/1/2010 ω 0.6 0.65 τ 3/10/2012 δ mean = 0.63 n = 923 0.6 d. ω, η (b) mean = 0.63 0.75 n = 1199 θ θ θ η µ 0.55 0.0 Sparse Medium Dense UnburnNone 2010 Pre-burn 2010 Sparse Medium Dense Canopy Density to a. δ2 H „ a a c 0.3 Snow Temperature (C) -6 -4 -2 -130 -140 -150 -150 -160 -160 -170 -170 -21 -20 -19 -18 -23 -22 -21 -20 -19 Unburn 2010 60 Conclusions and Implications 0 (b) 80 Pre-burn Unburn Post-burn 2010 2012 2012 60 40 40 20 20 Fig. 9 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 3 -4-4 -2-2 00 (a) (c) 80 80 0.0 100 100 60 60 40 40 40 40 20 20 20 20 -6 100 0.1 0.1 0.2 0.2 0.3 0.3 3 Snow density (kg/m3 ) Snow density (kg/m ) Snow Temperature (C) New Snow -190 80 0.4 0.4 -4 -2 Snow temperature 0.2 0.3 -6 -6 -4 -4 -2 -2 0 0 (b) (d) 0 0 0.0 0.0 0 0.1 0.1 0.2 0.2 0.3 0.3 -4 Rounds -6 -2 0 Small Facets (c) 80 60 60 40 40 20 20 0 0.4 0.4 3 Snow density (kg/m3 ) Snow density (kg/m ) Snow Temperature (C) 100 Crust layers 0.4 3 Snow density (kg/m ) Snow Temperature (C) Snow Temperature (C) 60 60 0.0 0.0 0.1 80 80 00 δ18O „ -2 (a) 80 -180 -18 -4 100 -6-6 100 100 -140 Snowfall Snowpack 6.2δ2H + 25.2 LMWL 8.1δ2H + 16.5 -6 0 Snow density (kg/m ) Snow Temperature (C) Snow Temperature (C) b. Snowfall Snowpack LMWL 8.0δ2H + 10 b 0.6 0 -130 -22 Fig. 7 0.0 Fig. 8 -23 0.3 100 0.0 -190 c Snow Temperature (C) 0.65 0.3 Evidence of Increased Snowpack Sublimation Following Disturbance -180 b 0.9 0.65 0.55 None Unburn 2010 Pre-burn 2010 0.6 (b) 0.9 η 0.3 a 0.0 0.55 Snow depth (m) SWE : P Snow depth (m) ε 0.55 c. a mean = 0.64 0.75 n = 746 π ε 1.2 0.75 0.9 Unburn 2010 Pre-burn 2010 (a) 0.0 • Isotopic enrichment of the snowpack relative to the local meteoric water line, suggests kinetic fractionation due increased sublimation following MPB disturbance (Fig. 8b). • The large facets in the Post-burn site (Fig. 9b) indicate strong temperature and vapor pressure gradients b. γ 1.2 0.9 mean = 0.62 n = 1766 β 0.65 None Sparse Medium Dense SWE:P (m/m) -100 0.2 North South 50 1.2 Snow depth (m) c. Snow depth (cm) 140 (a) 0.3 Snow depth depth (cm) Snow (cm) 50 none sparse medium dense Snow depth (m) 80 Snow depth (cm) 140 Depth [cm] • Snow surveys made at peak accumulation show a strong dependence on forest structure in healthy areas, where larger depths are associated with canopy gaps. • Spatial variability in snowdepths decline following loss of forest canopy by MPB (Fig. 4) and fire (Fig. 5). Mean = 0.094 m (d) Large Facets 0 • Despite a decrease in snow intercep?on following severe forest disturbance, there was liCle change (aEer MPB-­‐ effects) or a small decline in peak snowpacks (aEer fire). • Increased sublima?on is likely driving compensa?ng winter vapor losses due to increases in turbulence and/or radia?on following the loss of the forest canopy. • Snowpack energy balance modeling is needed to help quan?fy the importance of these compensa?ng effects. 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 3 Snow density (kg/m ) Please look for our papers submiCed to Ecohydrology: Biederman et al. (2012) and Harpold et al. (2012) Thanks to support from NSF for the Jemez Cri?cal Zone Observatory, NSF Pine Beetle Funding (Brook and Gochis), and NSF post-­‐doctoral funding (Harpold) 0.4 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 3 Snow density (kg/m ) Snow temperature Rounds New Snow Small Facets Crust layers Large Facets 0.4