Teacher Voice Omnibus May 2013 Survey Pupil behaviour Research Report

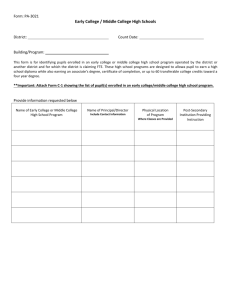

advertisement