THE IMPACT OF SUPERSTORM SANDY ON NEW JERSEY TOWNS AND HOUSEHOLDS

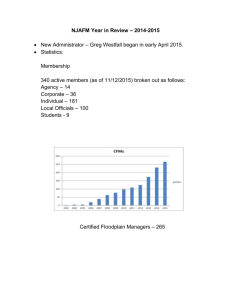

advertisement