Assessing impact submissions for REF 2014: An evaluation

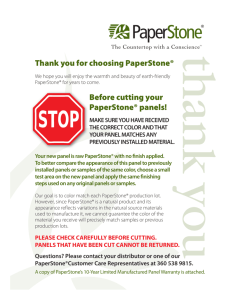

advertisement