WORKING PAPERS European Banking Union

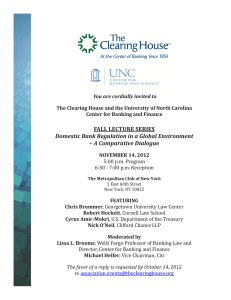

advertisement