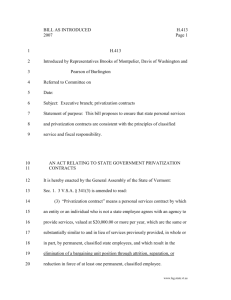

Working Paper Number 87 March 2006

advertisement