DO ENTREPRENEURS REALLY LEARN? EVIDENCE FROM BANK DATA Working Paper No. 98

advertisement

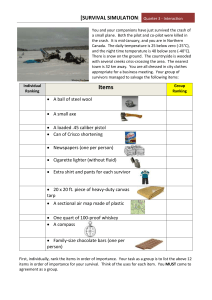

DO ENTREPRENEURS REALLY LEARN? EVIDENCE FROM BANK DATA Working Paper No. 98 June 2008 Julian S. Frankish*, Richard G. Roberts* and David J. Storey** Warwick Business School’s Small and Medium Sized Enterprise Centre Working Papers are produced in order to bring the results of research in progress to a wider audience and to facilitate discussion. They will normally be published in a revised form subsequently and the agreement of the authors should be obtained before referring to its contents in other published works. The Director of the CSME, Professor David Storey, is the Editor of the Series. Any enquiries concerning the research undertaken within the Centre should be addressed to: The Director CSME Warwick Business School University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL e-mail david.storey@wbs.ac.uk Tel. 024 76 522074 ISSN 0964-9328 – CSME WORKING PAPERS Details of papers in this series may be requested from: The Publications Secretary CSME Warwick Business School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL e-mail sharon.west@wbs.ac.uk Tel. 024 76 523692 2 Do entrepreneurs really learn? Evidence from bank data Julian S. Frankish*, Richard G. Roberts* and David J. Storey** *Barclays Bank plc **Warwick Business School Abstract: This paper examines the theory and evidence in support of entrepreneurial leaning (EL). Under this theory entrepreneurial performance is argued to be enhanced by EL which itself is enhanced by business experience. However, if business performance is strongly influenced by chance then evidence of EL will be difficult to identify. We test for EL using a large scale data set comprising 6,854 new firms. We choose business survival over two years as our performance measure and use three tests for EL. None of the three tests provide compelling evidence in support of EL. Keywords: start-up, survival, learning, chance. 3 1. Introduction Those familiar with the classic, tightly theorised, text by Casson (1982), will recall that author’s efforts to link entrepreneurship theory with the fictional Jack Brash. Casson says: “Jack Brash starts with very little information. But information is generated continuously as a by-product of his trading activity, and Jack uses this information to the full. He learns from the deals that he makes, and he learns from the deals that fall through. By analysing his experience he is able to turn adversity to advantage”, page 386-7. In his later writing Casson (1999) sees the key role of the entrepreneur as being to process information when that information is both costly and volatile. Casson postulates that the economic environment is continuously disturbed by shocks, which may be either transitory or persistent. The entrepreneur who runs a business has to respond to these shocks by making decisions – whether or not to invest in new plant and machinery, develop new products or services or shed labour. To make such decisions the entrepreneur is assumed to require costly information. However, not all entrepreneurs choose to collect the same amount of information and, even if they all had the same information, some make better decisions than others. Casson views the former as better entrepreneurs because of their greater skill in processing information. In terms of Jack Brash, if all individuals start with little information, then it is the ability of some to learn faster than others that distinguishes the successful entrepreneur from the less successful. But there are two powerful reasons for believing the opportunities for entrepreneurial learning (EL) may be limited or perhaps even non-existent. The first develops the Casson notion of shocks and asks what if these shocks are persistent and bear little resemblance to previous shocks that the entrepreneur has experienced? In this case learning cannot take place because each shock is different. The second is the role of chance in influencing entrepreneurial outcomes. Where outcomes are a random draw then, by definition, this excludes entrepreneurial learning (EL). This is most clearly reflected in the limited extent to which a lottery player can ‘learn’ from past experience to be more successful in the future. That individual may buy more tickets and so increase their chance of a win, but it does not imply they have ‘learnt to play the lottery’. So, despite its beguiling plausibility, EL is a concept that requires empirical support. Curiously, however, testing of EL has relied, as De Clerq and Sapienza (2005) point out, on asking the entrepreneur “how he or 4 she [the entrepreneur] has gained new insights or broader understanding”. They justify this on the grounds that “objective learning is nearly impossible to verify” 1 . This paper rejects that assertion and argues, following Casson, that if learning takes place it has to be reflected in enhanced entrepreneurial performance. This paper identifies three tests for the presence of EL that rely on the outcomes of learning rather than the self-reporting of learning. Our chosen measure of entrepreneurial performance is that of the survival/ non-survival of a new enterprise. The three tests assume that if learning takes place then an individual’s entrepreneurial talent, θ, would be expected to increase with time in business or with prior business experience 2 and so raise the likelihood of new firm survival. Our first, and most rudimentary, test examines whether individuals who have previously been business owners are more likely to start firms that survive than otherwise similar businesses established by those without that prior experience. Our second, and novel, test hypothesises that business owners who learn will become less likely to undertake actions that are clearly linked to endangering the survival of their business. Therefore, the test is whether, with increasing time in business, owners are less likely to undertake ‘life threatening’ actions when he or she knows that they are life threatening. The life threatening measure we identify is unauthorised borrowing from the Bank. The strength of this measure is firstly that we show it is strongly related to subsequent business closure and second that the firm is made aware of the risks because it is informed of this by the bank and charged a penal rate for such borrowing. The third test uses the metric of sales variance – which we call volatility. Unsurprisingly, we show that new firms with high volatility are less likely to survive, and our test asks whether business owners learn to reduce this volatility with greater experience. To undertake these tests we use a bespoke dataset of 6,854 wholly new firms that began to trade between March and May 2004. They are a sample drawn from all new firms in England and Wales, the structural characteristics of which are identified prior to start-up. These new firms are followed over their first two years after start-up, with their structural data supplemented every six months by a selection of variables capturing their trading performance. We find little evidence of learning on any of our three tests. Confirming the results of other large scale empirical work on the topic, we find no support for the hypothesis that new firm survival is enhanced by the owner having prior business ownership experience. Second, we find that whilst unauthorised borrowing is strongly related to subsequent business closure, there is no evidence that new business owners become less likely to borrow in this way with increased business experience. Finally, we find no evidence that sales volatility reduces the longer the business has been trading. 1 This may explain why the Special Issue of Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice devoted to EL comprised eight articles of which only two contained any form of empirical analysis, but neither of which examined individual entrepreneurs. 5 The key contribution of the paper is therefore to interrogate the concept of EL using an economic lens. It takes the survival of a new enterprise as the metric of success and concludes that, far from learning, the business owner continues to take actions that will undermine the business. We do not infer from this that the owner is not capable, but rather that learning cannot take place because the range of situations faced by the business owner is so diverse. Superimposed on this is the key role of chance. By this we mean that business owner A can make the ‘wrong’ decision many times and still survive, whilst business owner B makes this bad decision only once and has to close. We conclude that it is the greater role played by chance in new firm survival that explains why EL is much less likely to be present in such enterprises than in large established ventures. The remainder of the paper is set out as follows. Section 2 reviews and develops the theory of entrepreneurial learning and then assesses the extent to which such theories are supported by empirical evidence. Section 3 summarises some key empirical studies into firm survival. Section 4 presents our hypotheses derived from the literature review. Section 5 sets out the variables used to test these hypotheses. Section 6 provides a summary of our data. Section 7 presents estimated models of conditional firm survival, enabling a simple test of entrepreneurial learning and also using the estimates to derive a more sophisticated measure of θ. Section 8 uses this chosen measure of θ to test for entrepreneurial learning among firms that survive the first two years after start-up. Section 9 summarises the paper and offers some concluding points relating to theory development. 2. Theory and Evidence on Entrepreneurial Learning Harrison and Leith (2005) provide a comprehensive review of the literature linking organisational and entrepreneurial literature from a cognitive perspective. This literature sees the core of entrepreneurship as the study of opportunities – their origins, nature and evolution. In practice it emphasises the recognition of opportunities and empirical testing of the theory relies almost exclusively upon self-report data. This contrasts starkly with the economic approach that sees entrepreneurship as an exercise in constrained choice, albeit in conditions of imperfect information. The focus in economic analysis is upon clear outcomes – starting or closing a business, and it places little weight upon self-report data. This section provides a review of the economic literature relating to EL. As Casson (1982) implies, if an individual begins a new enterprise with little, or perhaps no, knowledge one simple inference is that those individuals that either begin with more knowledge and/or those that add 2 We recognise, following Jovanovic (1982) that the role of learning could be to provide the entrepreneur with a clearer assessment of their θ rather than leading to an increased θ. We however are not able to test this aspect of learning. 6 fastest to their stock of knowledge will have better performing businesses. One measure of performance is whether or not the business survives. However, even this simple linkage has been questioned. Jovanovic (1982) argued that the entrepreneurial ability of new entrepreneurs (translating into a profit function) is drawn from a known distribution, but that individual entrepreneurs are unable to discern their own ability prior to entry. Instead they form (and modify) a judgement of their ability based on actual performance. The result of this ongoing evaluation is the expansion of some new firms and the contraction of others, with ultimate closure when an opportunity cost threshold is breached. Although there is a stochastic element, the model results in those entrepreneurs with higher ability trading for a longer period and the conditional probability of exit declining with time. The crucial element of Jovanovic’s theory is that it does not assume that entrepreneurial talent θ improves over time. Time only enhances the ability of the individual to assess that talent. The value of that greater accuracy is that the individual is able to make a better informed judgement about whether or not to continue in business – the so called “stay or quit” decision (Taylor, 1999). A second variant is the ‘active’ learning model put forward by Ericson and Pakes (1989). Here a new entrepreneur is aware of their (and their competitors) level of ability. Unlike the passive learning model, the entrepreneur can influence the likelihood of higher profits in the future by undertaking investment that diminishes current profits, but could improve future ability and hence profits. The theoretical base provided by the ‘trading as learning’ concept has subsequently been developed in a number of ways. These include the introduction of financial resources and possible credit rationing (Evans and Jovanovic, 1989), and an explicit role for human capital (Cressy, 1996). A recent extension has been the scope for the entrepreneur to choose their market position (Cressy, 2006), defined in terms of selecting an optimal risk/return trade-off based on both their ability and their preferences. The above work implies that entrepreneurial learning (EL), in some form, both takes place and that it either helps the stay or quit decision, or directly enhances the individual’s entrepreneurial talent. However four plausible reasons why entrepreneurs do not learn are set out below: • Entrepreneurship is risky 3 and chance plays a key role 4 . The most valid analogy here is that starting a business can be compared with purchasing tickets to a lottery. The gambler buys tickets for this chance event because he observes that some people win a large sum of money and assumes that he may do likewise. Of course, if the lottery is truly a chance event then either the winners are lucky or they have 3 Depending on the measure, between 18% and 33% of new firms in England and Wales fail to survive for two years. See Charts A and B. 4 The justification for this is based on the weak explanatory power of models seeking to explain survival/ non-survival of small firms, and the inconsistency of key explanatory variables. For example see Bruderl et al (1992) or Cressy (1996). In his work on self-employment 7 bought more tickets. It does not imply that those who win have “learnt” how to play the lottery. The empirical question therefore is the extent to which business performance reflects θ and the extent to which it reflects chance 5 . • Entrepreneurs are optimists. The clear evidence from De Meza (2002) is that the self-employed – entrepreneurs – are considerably more optimistic than employees. He shows that, whilst both groups are optimistic, the ratio of expectations to actual achievement for the self-employed is more than 50% higher than for employees. Interestingly, De Meza also finds that these individuals are most optimistic about events over which they have least control. Hence, in the context of the lottery analogy above, it is optimists who buy more tickets. Since optimism is clearly equated with entrepreneurship, the fact that, in such a chancy environment, individuals continue to buy more tickets – start more businesses – reflects their optimistic personality rather than their ability to learn. It certainly does not provide evidence that the probability of winning increases with each ticket purchased – which is the implication of EL. • A third reason to be sceptical about EL is that no two business situations are identical. The individual who has been in business for some time may have not experienced, and thus be no more able to deal with, certain business situations than an individual with little or no experience. The analogy here is with the parenting of children. Given that children of the same parents are extremely variable, and the family context in which they grow up is very different, the notion that a parent with eight children is significantly more knowledgeable in dealing with their ninth child, compared with a ‘novice’ parent, seems a little fanciful. • Finally, the empirical evidence of entrepreneurial learning also looks weak. It is based, as De Clerq and Sapienza (2005) acknowledge, upon asking entrepreneurs about their learning experiences 6 . Such a methodology seems unlikely to tease out whether learning took place on the grounds that few such individuals would claim to have “learnt nothing and forgotten nothing” 7 . A more formal attempt to test for learning was made by Parker (2006). He shows that the self-employed adjust their behaviour only very marginally in the face of recent evidence. Instead they are much more strongly driven by their ‘priors’, which in this context we can take as their long-term experience and personality characteristics. So, how can we explain some frequently cited justifications for EL, as defined by some theorists? Henley (2004) says “over half the unexplained variance in the probability of choosing self-employment is accounted for as unobserved heterogeneity, suggesting that idiosyncratic influences have an important part to play in self employment status”. 5 One ‘explanation’ might suggest that entrepreneurs that succeed attribute this to talent, whereas those that do not attribute it to chance. 6 See for example Cope (2003). 7 Used by Talleyrand to describe the Bourbon restoration in France in 1815. 8 • It is frequently observed, particularly with reference to the United States, that currently highly successful business owners have previously owned a business that failed. The inference is that, because they are now successful, failure must have been ‘a learning experience’ for them. Unfortunately there are several problems with this ‘evidence’. The first is that the outcome is equally well explained by the lottery argument above. Here, even if business success is a chance event, an individual who continues to buy tickets for the lottery will enhance their probability of a win. It does not mean that they have ‘learnt to play the lottery’. It merely means they have bought more tickets. The second is that, to demonstrate evidence of ‘learning’ in a business context it is necessary to show, as a minimum 8 , experienced entrepreneurs – those that have previously owned businesses – have, all else equal, better performing businesses. The UK evidence (Ucbasaran, 2004) is that “after controlling for entrepreneurs’ human capital, the environment and other organisational characteristics, failed to detect any performance differences between novice and habitual entrepreneurs” 9 . The evidence from Germany (Metzger, 2006) is that prior business ownership experience does enhance subsequent performance, except where this was associated with business failure. Those individuals that failed have poorer performing businesses if they re-start. • A second observation is that in the United States there is much higher likelihood than in Europe of individuals, who have previously failed in business, then finding success with a later business. European policymakers have argued that this is because there is a ‘stigma of failure’ in Europe compared with the United States. They argue that Europe incurs an economic loss as a result of preventing failed entrepreneurs from being able to easily re-start. The fallacy of this argument is again illustrated by reference to the lottery. In essence one reason why individuals in the United States are more prepared to start a business again could be because the ‘price’ of the lottery tickets is lower in the United States than in Europe. In European countries there are more restrictions on a bankrupt individual in terms of the minimum time before that individual can re-start and the resources that they can draw upon to fund the restart. In short, the price of business failure is lower in the United States. So, if the price of lottery tickets is lower, as in the United States, more tickets will be bought and the chance of a win will increase. It does not reflect evidence of greater EL in the US, but rather a different emphasis upon responsibility to creditors. So what does this mean? 8 The more challenging test would be to demonstrate that the same individual performed better in each successive business, whilst also seeking to control for other factors influencing performance. 9 This quotation is taken from Ucbasaran et al (2006), page 474. 9 • First, the difficulty of being able to present persuasive evidence of EL leading to enhanced venture performance is not to be taken to imply that, in any sense, entrepreneurs are incapable of learning. Instead, what it does do is to re-balance our understanding of venture performance by placing a greater focus upon uncertainty. • Second, it does not imply that business performance is entirely a matter of chance, but merely that there is a very strong chance element in performance. • Thirdly, it does not imply that no entrepreneurs learn. That seems most unlikely, and it may be that those who do learn obtain a comparative advantage over those that do not. What is clear is that, when EL is tightly defined, the evidence that EL as a generalised phenomenon that can be assumed to take place is far from conclusive. • Finally the validity of using prior business ownership experience as a proxy for EL is limited. As we observed above the likelihood of re-entry varies between countries. It is also likely to vary between individuals and the circumstances in which they find themselves. In short, re-entrants are unlikely to be a random draw from the population – yet it is only re-entrants that can be the subject of this test of EL. What is needed is a better test of EL that comprises all owner-managers and not simply those who choose to re-enter. 3. Firm Survival: Key Empirical findings Empirical work on business survival has been undertaken across a number of countries (see Bruderl et al (1992), Mata and Portugal (1994) and Strotmann (2007) for studies outside of the UK and US). Despite using a range of analytical bases, several common elements in business survival have emerged fairly consistently. Survival appears positively related to firm size (whether defined by turnover, assets or employee numbers) and the length of time that a business has been operating. Some studies have also indicated that conditional closure rates take an inverted U-shape, rising up to a peak in the first few years before declining thereafter (Ganguly (1985), Cressy (1996)). Aside from size and age, studies have differed with regards to the factors influencing survival (or at least their relative importance). Some have indicated that industry-level factors, in the form of minimum efficient scale or the developmental stage of that sector, are relatively important (Audretsch (1991), Audretsch and Mahmood (1995), Agarwal and Audretsch (2001)). Others have found the scale of financial resources available to the firm to be a key element (Evans and Jovanovic, 1989). A third set have put forward individual and collective human capital (measured in a variety of ways) as the most important determining factors (Cressy (1996), Taylor (1999)). 10 However empirical studies of the factors influencing new firm survival are much more limited (Cressy (1996), Headd (2003)). Those undertaken have used one of two methods to examine survival rates. The first models survival over a set period after start-up (e.g. Bates, 1990). The second, and most prevalent, is by estimates a variant of a Cox proportional hazards model (Cox, 1972). This approach estimates a baseline conditional hazard function, with the relevant explanatory factors shifting this profile. While well established, these approaches have a particular limitation in that the estimated marginal effect of an explanatory factor is constant over time. This may provide a misleading indication of the role of a given factor at a particular point in time. The model presented by Cressy (2006) provides an example of marginal effects varying over time. Frankish et al (2006) addressed this limitation by estimating closure models for a number of distinct periods after start-up, and this approach is further developed in this paper. 4. Hypothesis Derivation We assume new firm founders would avoid taking actions that they knew would lead to closure of their business. However, new firm founders with low levels of talent θ might be unable to link their actions to the impact this has upon the business. Nevertheless, as their survival duration increases, this provides them with the experience – the learning opportunity – that enables them to make such a link. So, EL implies that even less able business founders would be less likely to take actions that endanger the survival of the business. Of course, the business owner can only learn – and change behaviour – if they are aware of the link between their actions and the survival of the business. The contrasting argument is that learning does not take place for two reasons. The first is that business is a random draw – as in the lottery – from which learning is impossible. The second is that as the business survives it encounters very different circumstances and situations from those that it has previously experienced. In simple terms, in the first six months of life of a new firm the skill may be to generate any orders at all; in the next six months it may be to satisfy those orders; in the third six months it may be to invest wisely in staff and equipment to satisfy the expansion of orders. All these may require different skills to overcome new and distinct challenges, with limited value from any learning derived from prior experience. Three tests of EL are undertaken: Test 1: Are new business owners that have previously owned a business were more likely to have a surviving new firm than otherwise similar business owners without that experience. Test 2: Are new businesses with more volatile sales more likely to subsequently close? Test 3: Are firms that borrow from the bank in an unauthorised manner more likely to subsequently close? 11 The details of Tests 2 and 3 are set out in Section 5 and the tests undertaken in Section 8. 5. Data: variables The data used in this paper are drawn from the customer records of Barclays Bank. Barclays provides the primary current account facility for 20% of businesses in England & Wales with turnover of less than £1 million. Their active customer base in this market is in excess of 500,000 firms. The size of this customer base makes it ideally suited for the purposes of this paper. Our data can be divided into three categories. First, the non-trivial issue of defining firm entry and exit. Second, the characteristics of the new business observable at start-up – their structural variables. Third, data on the performance of the new business after start-up – their trading variables. Entry/exit – start-up From the Barclays customer base we drew an initial sample of approximately 23,000 (non-financial) businesses that were start-ups with the bank during the three months from March to May 2004. This means that all of these firms opened their first business current account during this period. It is important to note that the opening of a business current account is not conditional on the provision of any other banking service, e.g. deposit account, overdraft, term loan, etc. We then refined our sample by selecting only those firms that showed evidence of trading activity in April to June 2004. This makes allowance for the fact that not all start-ups immediately commence trading. A sample firm was considered to have started up in the month prior to the first full month in which trading activity was observed. Crucially therefore this data base identifies new enterprises immediately they begin trading. – closure Obtaining a clear definition of closure required two constraints to be placed on our initial sample. First, firms that were identified at closure as switching to another bank were excluded in their entirety. Second, firms that recorded two consecutive periods of zero turnover were considered to have closed in the first of these periods. This adjustment makes allowance for any delay in removing inactive accounts from Barclays customer base. 12 Structural Our selection of structural variables reflect both those shown to be significant in previous studies of new/small firms (Storey, 1994) and the data available on Barclays customers. They can be further divided between those relating to the owner and those characterising the firm. For the owner the selected variables are the (mean) age of the business owner (Cressy, 1996), their educational attainment (Bruderl, Preisendorfer and Zeigler, 1992), their gender (Carter et al 1998), prior business experience (Headd, 2003) and the sources of advice/support approached prior to start-up (Meager, Bates and Cowling, 2003). The latter two were obtained by means of a set of voluntary questions asked of start-ups as part of this study. The business variables are the legal form of the start-up (Harhoff et al, 1998), its business sector (Mata and Portugal, 1994) and the number of business owners (Headd, 2003). Trading Our choice of trading variables was influenced by theory as well as prior empirical work, requiring the construction of previous unused measures of risk. Our conventional trading measures are the size of the firm – measured by debit turnover – and the use of authorised overdraft facilities. The latter is split into two variables. One showing if any use was made during a period, the second captures the degree of use. The estimation of a model for each period also permits the inclusion of variables showing the change in these base measures. – unauthorised borrowing and volatility This paper uses two metrics that clearly reflect cash flow, which both labour market and accounting theorists argue are related to firm survival. Labour market theories present business survival as a continual choice between the relative utility of self-employment, compared with switching to becoming an employee (Jovanovic (1982), Cressy (2006)). Lower volatility moves the business away from the threshold for ceasing trading, so reducing the likelihood of closure. The significance of the volatility index is also compatible with Gambler Ruin Theory in accounting. This sees the business owner having a stock of liquidity that is enhanced by ‘wins’ and reduced by ‘losses’. When the stock is exhausted the gambler/ business owner quits (Laitinen and Laitinen, 2001). Clearly where earnings are more volatile there is a greater likelihood that resources will be exhausted and that the owner will quit. We now describe the metrics used to capture these concepts. The first is unauthorised borrowing. This can occur in two ways. The first relates to overdrafts. In the UK, banks may choose to provide firms with an overdraft facility of, for example, £10,000. This enables the firm to borrow up to that amount generally for short periods, to overcome variations in cash flow. Interest is paid only 13 on the amount borrowed rather than on the full £10,000 as would be the case for a term loan. The disadvantage is that, if the limit is exceeded, the bank both charges a penal interest rate and informs the firm that the overdraft contract is breached. The overdraft facility can also be cancelled with immediate effect. In the context of this paper this makes excess use of overdraft a valuable measure for two reasons. The first is its link with closure, but the second is that the business owner is informed shortly after this happens. The merit of this is that because the bank writes to the business owner there can be no ambiguity over a lack of awareness on the part of the owner that they are taking a risky action. In short the owner is clearly informed and normally given the opportunity to ‘learn’. The second way unauthorised borrowing takes place is where, although no facility is made available by the bank, the firm makes a payment when it has no resources. Again the firm would be informed and be charged penal rates. Our second metric seeks to captures within period fluctuations in trading activity, on the grounds that new firms exhibiting high fluctuations will have difficulty managing their cash flows in these extreme situations. To address this we construct a volatility variable. This is the ratio of the standard deviation of monthly turnover to the mean monthly turnover in a six month period. This ratio (with a maximum value of 2.236) provides a standardised measure of cash-flow volatility across the varying firm sizes in the sample base. For those firms with a turnover of zero during a period (and therefore a denominator of zero) the ratio measure is set to zero. Of the two metrics, the unauthorised borrowing measure has the desirable quality that it is not only likely to be linked to survival, but it is also one where we know the business owner is informed and thus has the explicit opportunity to learn. Its disadvantage is that it does not apply to all firms as not all borrow in this manner. In contrast, our volatility measure applies to all firms, but their owners are not made aware of this in the same explicit manner. In this instance the opportunity for learning is less clearly identified. Overall The net effect of applying restrictions on the definition of start-up and closure, together with the requirement for completeness of data in the remaining sample, reduced the initial sample of 23,000 start-ups to a final sample base of 6,854 new firms 10 . 6. Data: summary Brief descriptions of the variables used in this paper are set out in table 1. Valuable insights into the characteristics of the sample are provided in Tables 2 and 3 and Charts A and B. The tables set out the 10 The non-UK reader might be interested that the government department with responsibility for small business statistics (Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform) lists Barclays as one of the main sources of data for both start-up numbers and business survival. This is to overcome the problem that the main official data source, VAT registered businesses, excludes the majority of firms with annual sales of less than £67,000 (for the tax year 2008/09). 14 structure of the sample at both start-up and over time, while the charts show survival and conditional closure rates. We now review all four. Chart A shows that the two year survival rate of new firms in our sample is 73%, similar to the survival rates estimated over approximately the same period by Barclays using both the turnover of new current accounts and the length of time that start-ups remain with them. The sample survival rate is, however, markedly lower than that derived from official data – the VAT register – where the two year survival rate is 82%. This difference is primarily a result of the high threshold for compulsory registration (see footnote 10), resulting in most new VAT firms being both not start-ups and relatively large 11 . Chart B shows the conditional closure rates experienced by the sample in the two years after start-up. This reveals that our sample experienced a closure profile in keeping with the classic inverted U-shape seen in previous analytical work, with closure rates peaking 12 to 18 months after start-up. Tables 3 and 4 offer important initial insights into the factors associated with business survival. Table 3 shows how the distribution of structural variables in the sample changes over the two years after start-up. In this period there are three significant shifts. First, the proportion of companies increases by four percentage points. Second, there is a rise in the proportion of middle-aged (35-44) owners. Finally, firms with multiple owners are more prevalent. This implies that these characteristics are associated with business survival, although these univariate results do not make allowance for associations between structural variables. Table 4 sets out data on the sample’s trading variables for each of the four six months periods in our analysis. It shows that the median annual turnover is a little over £30,000, with no indication of significant growth for a typical surviving firm in these two years. On our bespoke measure, the volatility of turnover declines between periods 1 and 2 (up to 6 months and 6-12 months after start-up), but then remains broadly unchanged. The sample also shows an increasing incidence of excess overdraft use over time, with the length of time in this state also increasing from period to period. 7. Analysis: new firms survival in the first two years The conventional method for analysing business survival is a conditional hazard model (Sanatarelli and Vivarelli, 2002). This approach estimates a hazard function for survival where time enters as an explanatory variable in its own right. Other factors then serve to shift this baseline function, but usually with constant marginal effects over time. 11 What is not an explanation is that the Barclays closure rate includes those switching to other banks, since these are eliminated from the sample. Known ‘switchers’ in their first two years are minimal. Fraser (2005) for example finds that only 2% of all UK SMEs switched banks in the previous three years. This is likely to be lower for very new businesses. 15 However, given the unique characteristics of our data we do not need this assumption. Indeed we are able to show the assumption is invalid. Using a series of binary logistic regression models, we examine the factors influencing survival/non-survival for each of the four six month periods in the dataset – described as periods 1 to 4 respectively. This method produces estimates how the likelihood of survival in each period is associated with our structural and trading variables. By definition, in period 1 only the structural variables are available. For the subsequent models the variables expand to include first the levels of our trading variables (period 2) and then their changes (periods 3 and 4), outlined in section 5. Table 5 presents the estimates and other model information for each of the four resulting models. The results from Table 5 offer important insights into the relative roles of structural and trading data in accounting for business survival. They support the view that observing even a short period of business activity sheds more light on the likelihood of short-term survival than a range of structural data on human capital and firm characteristics. The explanatory power of model (1), covering the first six months after start-up and restricted to only structural variables, is very limited compared with those for models (2) to (4) that have additional data on business activity. Likelihood ratio tests confirm that the addition of business activity data in (2)-(4) significantly improves the explanatory power of those models. Comparison with the log-likelihood scores for models restricted to structural variables (not shown) indicate that business activity data provides between 80% and 90% of the explanatory power of the full models. Table 5 indicates that business survival is shaped by a core set of variables supplemented with a changing set of additional factors. The core of the models is provided by three factors – size/growth of the firm, volatility/change in volatility and the proportion of time with excess overdraft use. Each of these factors is significant (with the same sign) in each period for which they are available. What do these three factors tell us about the processes shaping business survival? First, the estimates confirm results contained in prior analytical work regarding the positive relationship between firm size and survival. Second, the negative influence of volatility, taken together with the estimates for size, are consistent with theoretical models that characterise business survival as involving an income threshold, determined by a reservation wage, that sets the minimum requirement for continued trading. Third, the negative impact of high levels of excess overdraft use may imply limitations in the financial management skills of an owner-manager to operate within their financial constraints. Importantly, in terms of our subsequent discussion, lower volatility makes it less likely that the critical threshold will be breached for any given size of firm. The estimates also indicate that, for volatility, change is as important as the absolute level. A firm that experiences higher/lower volatility than in the previous period 16 has a higher/lower probability of closure. Changes in volatility from any starting point may cause the ownermanager to re-evaluate both their own ability and the nature of the market in which they are operating. In addition to the core factors, there are a few other significant variables that are important to highlight. One is the significance, in some of the models, of simply being in excess, in addition to the degree of excess noted above. It is particularly interesting to contrast the role of excess overdraft use, with the absence of any significant impact from using an authorised overdraft facility. This indicates that our focus on the former is the right one in testing EL. Another factor is the positive association of incorporation and survival. This variable probably acts a control for the aims and objectives of the owner, with a corporate form offering greater flexibility for future growth and financing 12 . Finally, there is the impact of male owners. This is significant in each of the models, but with a positive association in models (1) and (4) contrasting with a negative one in models (2) and (3). it is unclear what should be drawn from these estimates. The remainder of the estimates contain factors that exert influence in only one or two periods at best. For example, higher education does reduce the likelihood of non-survival, but only in the first six months. After that it has no influence. Other variables appear to exert no significant influence in any period. We now turn to the insights into EL provided by the data. 8. Analysis: entrepreneurial learning (EL) Section 3 ended by setting out three tests for Entrepreneurial learning: Test 1: Are new business owners that have previously owned a business were more likely to have a surviving new firm than otherwise similar business owners without that experience. Test 2: Are new businesses with more volatile sales more likely to subsequently close? Test 3: Are firms that borrow from the bank in an unauthorised manner more likely to subsequently close? Test 1 Table 3 shows that only about 12% of new firm founders have no personal or family experience of business ownership, whereas almost one-half have both family and personal experience. In addition about a quarter have personal but no family experience. However, change in these proportions over the two years after startup is limited, implying that business experience, of whatever form, has no significant influence on survival. This is confirmed in table 5 where none of the ‘experience’ variables are significant, at the 5% level, in accounting for business survival in any of the six month periods. These estimates confirm the findings of Ucbasaran (2004), but contradict those of Headd (2003). 17 Test 2 We argued above that, with suitable controls, the ability to control sales volatility could be taken as a measure of EL. We also showed that our volatility measure was a core significant factor in accounting for short-term survival. The most obvious control required is to take account of changes in sample composition over time. That is, the volatility of firms in period 4 may be lower than that in period 1 as a result of the closure of more volatile (less able) firms in the interim. Chart C shows the distribution of volatility in periods 1 and 4 for the 5,026 firms that were open across the full two years. An initial inspection of the chart shows volatility was lower in period 4 than period 1, with a marked shift to the left (lower volatility) in the modal point of the distribution. It is also interesting to note the shift of firms to the extremes of the distribution, with 1.1% of the sample located there initially, rising to 4.9% in period 4. This polarisation indicates that irregular trading patterns are perhaps more common that might be expected. However, table 2 shows there is a significant negative correlation between volatility and turnover in each period. To address this we now use an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) approach to model volatility as a function of the other data in our sample. In addition, we include a set of additional dummy variables representing periods 2 to 4. If, having controlled for other firm characteristics, these latter variables are significant, then it would indicate that there is a distinct time component to volatility. If this time component is negative, i.e. lower volatility over time, then we might conclude that some degree of entrepreneurial learning is occuring. For the OLS model the data was restructured such that each firm-period combination was a distinct observation, i.e. each surviving firm appears four times, one for each period. This provided 20,104 observations in total. Other data was also reconfigured as appropriate, e.g. a series of dummy variables representing legal form, sector and variables such as educational attainment. In addition, a model was also estimated excluding extreme volatility values 13 in order to check the robustness of the initial results. Table 6 sets out the estimates and summary data for both models. Therefore, test 2 is that the presence of EL implies lower volatility over time. A compelling case for EL would be if volatility were to be significantly lower in each successive six month period. Table 6 shows that volatility is significantly lower in periods 2 to 4 than in period 1. However, the estimates do not provide a similarly clear picture with regards to the relative change in volatility between these latter periods. The coefficients and standard errors from the full model indicate that there is no significant difference 12 In our sample the two year survival rate of companies is 81%, rather than the 68% for sole traders. Whilst there is empirical evidence that legal form is clearly linked to small enterprise growth, the prior picture on survival is less clear (Harhoff et al, 1998). 13 A value of zero or 2.236 (the maximum value) for the vol variable. 18 in volatility across the three periods, while the trimmed model actually indicates that volatility is higher in period 4 than periods 2 and 3 14 . One possibility is that the estimates capture the inherent volatility of the period immediately after start-up. That is, the push to establish the business – building contacts, sales and the like – produces unavoidably erratic trading. When the first six months is over, the business is more likely to have ‘settled down’, reflected in commensurately lower volatility. On this interpretation the estimates do not indicate the presence of entrepreneurial learning, rather they are saying something about the nature of the start-up process. An alternative interpretation is that the improvement after the first period there is some slipping back at the end of the two year period. This may mean that any enhanced ability gained from surviving the start-up phase maybe of more limited or reduced benefit when facing the challenges of developing a more established business. Test 3 It will be recalled that there are limitations in using volatility as a measure of EL. More specifically that although the owner may be vaguely aware that sales volatility is undesirable, it is not something about which he is continually reminded. Our third test – that of unauthorised borrowing – satisfies this requirement. The evidence from table 5 is that in each of the periods 2 to 4 unauthorised borrowing in the previous period is associated with closure in the current period. Further, when there is excess use of an overdraft facility the business owner is both informed and effectively ‘fined’ by being charged a penal rate. Therefore, our test is whether, in spite of being reminded and penalised, the new business owner continues to be equally likely to borrow in this manner in the future. Looking at table 4 we see that both the incidence and magnitude of excess borrowing rise over time. The proportion of our sample having some unauthorised use rises from 30% in period 1 to 33% in period 4. Similarly, the mean proportion of the period spent in this state rises from 4.2% to 6.3%. The mean changes in both of these variables indicates that surviving firms are more, not less likely, to experience periods of excess use over time. The picture in table 4 is reinforced by the data in table 2. This shows a clear positive correlation between the length of time in excess across all periods. So, despite the warnings from the bank new firm owners appear equally likely to undertake this form of risky borrowing, whether their businesses are six, twelve, or eighteen months old and that doing so significantly increases their likelihood of short-term closure. 14 Although the reduction in volatility compared to period 1 remains significant. 19 9. Conclusion This paper has examined the issue of entrepreneurial learning (EL). We have reviewed the theory, both in support of, and in conflict with, EL and concluded that on theoretical grounds the concept could neither be accepted nor rejected. The paper conducted three empirical tests of EL. We argued that prior tests, which used the self-reported responses of entrepreneurs, were imperfect. Instead our tests used business survival as the key performance measure. Test 1, which has been undertaken previously, was whether, all else equal, new businesses founded by individuals with prior business ownership had higher survival rates than those which did not. We showed that prior business experience as an owner had no substantial positive influence on short-term survival rates in the two years after start-up. Tests 2 and 3 were more sophisticated and can only be undertaken with bank data. Underlying these tests was the notion that EL would be supported if the owner-manager became less likely to engage in ‘Life threatening’ actions over time. The two life threatening actions we examined were allowing sales to be highly volatile and borrowing from the bank in an unauthorised manner. Of the two we made the case that the unauthorised borrowing was the conceptually stronger measure since the business owner was informed when this happened and charged a penal interest rate. Our findings were that both measures were indeed strongly associated with subsequent business closure. However, further analysis did not indicate any clear evidence of EL. While volatility was lower after the initial six months, there was no evidence of continuing improvements over time, something we would expect with EL. Similarly, our sample showed no reduced propensity to excess overdraft use over time. Indeed, the data indicated that, if anything, the incidence of excess and its intensity both rise as firms move further from startup. Both of these results suggest that the existence of EL is, at best, unproven. In addition to our core tests regarding EL, we also showed that the factors associated with business survival in each six month period over two years do vary. However, there are also a set of core factors shaping the likelihood of continued trading – size/growth, volatility/change in volatility and the proportion of time in excess. However, one variable that does not appear as a consistent significant factor is prior business ownership. Overall, this paper has presented a large scale analysis of business survival and entrepreneurial learning. The results show that while a variety of changing factors shape business survival in the two years after startup, within this there is a clear core covering growth, volatility and financial management. The significance of these variables provides strong support to models of business survival that characterise continued trading as an ongoing comparison of business ownership with the utility derived from the best alternative activity 20 available. The results also show that there is a significant drop in volatility for firms after the first six months. However, the absence of a clear pattern for changes in subsequent periods means that it is not possible to conclude that entrepreneurial learning is present. It suggests that EL is not a ‘one way bet’ as is often portrayed. Instead the role of chance and the vastly different circumstances facing the new firm founder may explain why it is difficult for EL to take place for most new firm founders. 21 References Agarwal, R. and Audretsch, D.B., 2001; ‘Does Entry Size Matter? The Impact of the Life Cycle and Technology on Firm Survival’, The Journal of Industrial Economics, XLIX(1), 21-43. Audretsch, D.B., 1991; ‘New Firm Survival and the Technological Regime’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 68(3), 441-50. Audretsch, D.B. and Mahmood, T., 1995; ‘New Firm Survival: New Results Using a Hazard Function’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 77(1), 97-103. Bates, T., 1990; ‘Entrepreneurial Human Capital Inputs and Small Business Longevity’, Review of Economics and Statistics, LXXII(4), 551-9. Bruderl, J., Preisendorfer, P. and Ziegler, R., 1992; ‘Survival Changes of Newly Founded Business Organisations’, American Sociological Review, 57(2), 227-42. Carter, N.M., Williams, M. and Reynolds, P.D., 1997, ‘Discontinuance amongst New Firms in Retail: The Influence of initial resources, strategy and gender’, Journal of Business Venturing, 12(2), 125-145. Casson, M.C., 1982; The Entrepreneur: An Economic Theory, Martin Robertson, Oxford. Casson, M.C., 1999; ‘Entrepreneurship and the theory of the firm’ in Acs, Z.J., Carlsson, B. and Karlsson, C. eds., Entrepreneurship, Small and Medium Sized Enterprises and the Macro-economy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Cope, J.P., 2003; ‘Entrepreneurial learning and critical reflection: discontinuous events as triggers for high level learning’, Management Learning, 34(4), 429-50. Cox, D.R., 1972; ‘Regression Models and Life Tables’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 34(2), 187-202. Cressy, R.C., 1996; ‘Are Business Startups Debt-rationed?’, The Economic Journal, 106 (4), 1253-70. Cressy, R.C., 2006; ‘Why do Most Firms Dies Young?’, Small Business Economics, 26, 103-16. De Clerq, D. and Sapienza, H., 2005; ‘When do Venture Capital Companies learn from their Portfolio Companies?’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 517-535. Ericson, R. and Pakes, A., 1995; ‘Markov-perfect industry dynamics: a framework for empirical work’, Review of Economic Studies, 62, 53-82. Evans, D. and Jovanovic, B., 1989; ‘An Estimated Model of Entrepreneurial Choice Under Liquidity Constraint’, Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 808-27. Frankish, J., Roberts, R. and Storey, D.J., 2006; ‘Charting the Valley of Death – Closure Rates Among New Businesses’, Paper for ISBE 29th National Conference, 30 Oct-1 Nov 2006. 22 Fraser, S., 2005; ‘Finance for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises’, Bank of England, London. Ganguly, P., 1985; UK Small Business Statistics and International Comparisons, Small Business Research Trust, Harper Row, London. Harhoff, D., Stahl, K. and Woywode, M., 1998; ‘Legal form, Growth and Exit of West German firms: Empirical results for Manufacturing, Construction, Trade and Service Industries’, Journal of Industrial Economics, 46(4), 453-488. Headd, B., 2003; ‘Re-defining Business Success: Distinguishing between closure and failure’, Small Business Economics, 21(1), 51-61. Henley, A., 2004; ‘Self-Employment Status: The Role of State Dependence and Initial Circumstances’, Small Business Economics, 22(1), 67-82. Jovanovic, B., 1982; ‘Selection and Evolution in Industry’, Econometrica, 50(3), 649-70. Laitinen, E.K. and Laitinen, T., 2001; ‘Bankruptcy prediction Application of the Taylor's expansion in logistic regression’, International Review of Financial Analysis, 9(4), 327-349. Mata, J. and Portugal, P., 1994; ‘Life Duration of New Firms’, The Journal of Industrial Economics, XLII(3), 227-45. Meager, N., Bates, P. and Cowling, M., 2003; ‘An Evaluation of Business Start up support for Young People’, National Institute Economic Review, 186(October), 59-72. Metzger, G., 2006; ‘Once bitten twice shy? The performance of entrepreneurial re-starts’, Discussion Paper 06-083, ZEW, Mannheim. Parker, S.C., 2006; ‘Learning about the Unknown: How fast do Entrepreneurs adjust their beliefs?’, Journal of Business Venturing, 21(1), 1-26. Phillips, B. and Kirchhoff, B., 1989; ‘Formation, Growth and Survival; Small Firm Dynamics in the US Economy’, Small Business Economics, 1(1), 65-74. Santarelli, E. and Vivarelli, M., 2002; ‘Is subsidising Entry an Optimal policy?’, Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(1), 39-52. Storey, D.J., 1994; Understanding the Small Business Sector, Routledge, London. Strotmann, H., 2007; ‘Entrepreneurial Survival’, Small Business Economics, 28(1), 87-104. Taylor, M., 1999; ‘Survival of the Fittest? An Analysis of Self-employment Duration in Britain’, The Economic Journal, 109(454), 140-55. Ucbasaran, D., 2004; ‘Business Ownership Experience, Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Performance: Novice, Serial and Portfolio Entrepreneurs’, Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Nottingham University Business School. 23 Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P. and Wright, M., 2006; ‘Habitual Entrepreneurs’ in The Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurship, Casson, M., Yeung, B., Basu, A. and Wadeson, N. eds., Oxford University Press, Oxford. 24 Table 1: Variables & definitions Dependent op1 op2 op3 op4 = 1 if start-up is still open at the end of period 1 (6 months) = 1 if start-up is still open at the end of period 2 (12 months) = 1 if start-up is still open at the end of period 3 (18 months) = 1 if start-up is still open at the end of period 4 (24 months) note: these variables are conditional on the firm being open at start of period t Structural legal sic age age_sq involve_xs involve_male educate bus_exp advice_x legal form of start-up: company (including LLP), partnership or sole trader business sector of firm at start-up: agriculture, manufacturing, construction, motor trades, wholesale, retail, hotels & catering, transport, property services, business services, health, education & social work (hesw) or other services age of start-up owner-manager(s) square of age = 1 if more than a minimum number of owner-managers of the start-up: company 2+, partnership/LLP 3+ = 1 if there is at least one male owner-manager of the start-up highest educational attainment of owner-manager(s): none, GCSE, A-level, Degree or higher previous business experience of owner-manager(s): none, family, self, self & family advice/support sough prior to start from: enterprise agency/business link (entbl), accountant (acc), solicitor (sol), college (coll), (Barclays) start right seminar (srs), the princes trust (pybt), family (fam), other (oth) Trading turn_ln turn_ln_c vol vol_c limuse limuse_c limpc limpc_c xs xs_c xs_days xs_days_c log turnover for the period t-1 the change in turn_ln from period t-2 to t-1 ratio of the standard deviation of monthly turnover to the mean monthly turnover in period t-1 the change in vol from period t-2 to t-1 = 1 if authorised overdraft used at any time in period t-1 the change in limuse from period t-2 to t-1 mean proportion of authorised overdraft limit used during period t-1 the change in limuse from period t-2 to t-1 = 1 if in excess of authorised overdraft limit at any time in period t-1 the change in xs from period t-2 to t-1 proportion of period t-1 in excess of authorised overdraft limit the change in xs_days from period t-2 to t-1 25 Table 2: Correlation matrix Continuous variables only Pearson Correlation turn_ln(1) turn_ln(1) 1.000 ** turn_ln(2) .748 ** turn_ln(3) .650 ** turn_ln(4) .588 ** vol(1) -.392 ** vol(2) -.372 ** vol(3) -.326 ** vol(4) -.263 ** limpc(1) .096 ** limpc(2) .091 ** limpc(3) .137 ** limpc(4) .036 ** xsdays(1) -.180 ** xsdays(2) -.091 ** xsdays(3) -.042 ** xsdays(4) -.039 turn_ln(2) turn_ln(3) turn_ln(4) vol(1) vol(2) vol(3) vol(4) limpc(1) limpc(2) limpc(3) limpc(4) xsdays(1) 1.000 -.001 .005 1.000 xsdays(2) xsdays(3) xsdays(4) 1.000 ** .764 ** .701 ** -.410 ** -.430 ** -.453 ** -.337 ** .065 ** .077 ** .145 ** .037 ** -.103 ** -.167 ** -.075 ** -.063 1.000 ** .769 ** -.347 ** -.481 ** -.416 ** -.431 ** .044 ** .038 ** .116 .025 ** -.057 ** -.116 ** -.150 ** -.099 1.000 ** -.279 ** -.406 ** -.464 ** -.410 ** .061 ** .079 ** .074 ** -.055 ** -.040 ** -.128 ** -.175 ** -.194 **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). note: ( ) indicates the period the variable relates to 1.000 ** 1.000 .436 ** .359 ** .305 ** -.066 ** -.060 ** -.095 -.012 .481 ** .459 ** -.055 ** -.061 ** -.107 -.015 ** ** .124 ** .038 -.001 .003 ** .075 ** .143 ** .042 ** .042 1.000 ** .487 ** -.053 -.024 ** -.077 .007 .023 ** .059 ** .109 ** .040 1.000 ** -.057 ** -.081 ** -.069 -.023 -.022 .012 .018 .070 ** 1.000 ** .338 ** .281 .010 ** .082 ** .038 ** .056 .004 1.000 ** .342 ** .050 ** .036 ** .092 ** .124 ** .092 1.000 ** .060 ** .048 ** .063 ** .189 ** .140 * .030 ** .094 ** .491 ** .298 ** .182 1.000 ** .566 ** .372 1.000 ** .518 1.000 Table 3: Structural variables, summary data % of surviving sample base legal company sole trader sic manufacturing construction retail hotels & catering business services personal & leisure services age under 25 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65 & over involve_xs involve_male bus_exp none family self self & family educate none GCSE A-level Degree or higher advice_x enterprise agency/business link accountant solicitor family/friends other any two or more Sample size At start-up After 24 months 38.2 48.7 42.4 45.0 5.1 14.5 11.6 8.8 26.4 16.7 5.4 14.8 11.1 8.2 26.8 16.3 6.9 30.9 34.9 19.2 7.2 0.9 16.3 81.3 5.8 29.1 35.8 20.8 7.6 0.9 18.5 82.1 12.4 15.3 24.3 48.0 11.9 14.8 24.2 49.0 22.5 32.6 17.1 27.8 22.0 32.5 17.2 28.4 10.4 36.4 5.3 30.2 11.6 50.3 11.4 10.0 37.6 5.5 29.3 10.5 50.4 11.0 6,854 5,026 Table 4: Trading variables, summary data period turnover (£) mean median turnover (t0 – t1) mean median vol mean median vol_c mean median overdraft limit (% of sample) limuse (mean) limuse_c (mean) limpc mean median limpc_c mean median xs (mean) xs_c (mean) xs_days mean median xs_days_c mean median Sample size (1) (2) (3) (4) 51,000 13,800 58,900 15,300 65,700 17,100 68,000 16,300 +7,100 +500 +5,200 +300 -1,300 -400 .76 .62 .68 .52 .64 .47 .66 .49 9.4 -.04 -.06 20.6 +.02 -.01 25.2 +.07 +.03 26.7 .046 .119 .070 .170 .051 .180 .008 .011 0 .040 0 .071 0 .137 0 +.028 0 .306 .025 +.032 0 .327 .043 +.067 0 .330 .011 .056 0 .063 0 .069 0 +.026 0 +.023 0 +.016 0 5,974 5,351 5,026 .299 .042 0 6,587 28 Table 5: Conditional survival models period model legal [sole trader] company partnership sic [wholesale] agriculture business services construction hesw hotels & catering manufacturing motor trades other services property services retail transport age age_sq involve_xs involve_male bus_exp [none] family self self & family educate [none] GCSE A-level Degree advice_entbl advice_acc advice_sol advice_coll advice_srs advice_pybt advice_fam advice_oth (1) (2) (3) (4) .598*** .045 .295** -.177 .195 -.258* .499*** -.236 1.385 .012 .254 -.191 -.121 .314 .084 .073 .598 -.196 .138 .107*** .000** .102 .424** 1.478** .540* .769** .743* .133 .643* -.109 .580* 1.015*** .539* .144 .035 .000 .475** -.332*** .304 -.544 -.731* .249 -.826* -.687 -.245 -.674 .253 -.716* -.620 .032 .000 .137 -.208* .663 .738* .609 .459 .304 .915* .674 .896** 1.267** .256 .070 -.043 .001 .229 .359* -.183 -.154 -.194 .337** -.029 .222 .120 -.024 -.028 .232 -.439* -.208 .041 .186 .515** -.255 -.082 .108 .347 -.877* -.177 -.325** -.507** .018 .074 .211 .420** -.030 .440* -.040 -.066 -.670** -.086 -.093 .204 .088 .149 -.143 -.070 .090 -.073 .221 -.556 -.037 -.181 -.100 .374 -.329 -.174 .095 -.504* -.278 2.294* .777 .100 -.012 .149*** .072** .164*** -.887*** -.464*** -.358 -.067 1.288 -1.284 -.612*** .649*** -1.629*** -1.539*** .232*** .062* -1.639*** -.554*** -.088 .311 -.963 .768 -.380 .417** -2.225*** .131 turn_ln turn_ln_c vol vol_c limuse limuse_c limpc limpc_c xs xs_c xs_days xs_days_c -1.259*** .216 .433 -.329*** -2.947*** constant .980 1.777*** 3.017*** 4.621*** Number of observations 6,854 6,587 5,974 5,350 2155.290 101.182*** 3326.657 751.562*** 3133.118 862.267*** 1570.034 880.478*** -2 Log likelihood 2 χ significant at ***1% level, **5% level, *10% level note: for categorical variables the entry marked [ ] represents the base case for the models 29 Table 6: Volatility models Firms surviving first two years after start-up model period_2 period_3 period_4 legal [sole] comp part sic [who] agr bus con hesw hot man motor per prop ret tran age involve_xs involve_male bus_exp [none] fam self self_fam educate [none] nvq2 nvq3 nvq4 advice_entbl advice_acc advice_sol advice_coll advice_srs advice_pybt advice_fam advice_oth turn_ln limuse limpc xs xs_days constant Number of observations F-statistic 2 Adjusted R all observations standard error excluding max & min volatility standard error -0.085*** -0.108*** -0.094*** 0.009 0.009 0.009 -0.078*** -0.096*** -0.044*** 0.008 0.008 0.008 0.067*** 0.006 0.008 0.010 0.075*** 0.012 0.008 0.009 -0.040 -0.022 -0.058*** -0.082*** -0.110*** -0.065*** -0.076*** -0.069*** 0.091*** -0.084*** -0.080*** 0.001*** 0.032*** 0.011 0.037 0.021 0.022 0.029 0.023 0.025 0.027 0.022 0.025 0.023 0.026 0.000 0.010 0.009 -0.061* -0.041** -0.076*** -0.099*** -0.111*** -0.074*** -0.077*** -0.093*** 0.101*** -0.078*** -0.089*** 0.000 0.032*** 0.018** 0.033 0.019 0.020 0.026 0.021 0.022 0.024 0.020 0.023 0.020 0.024 0.000 0.009 0.008 -0.013 -0.022** -0.011 0.013 0.011 0.011 -0.021* -0.014 0.006 0.011 0.010 0.009 -0.037*** 0.021** 0.066*** -0.051*** -0.022*** 0.016 -0.028* 0.089** -0.016 -0.005 0.013 -0.083*** -0.071*** -0.006*** -0.029*** 0.292*** 0.009 0.010 0.010 0.011 0.007 0.014 0.017 0.039 0.034 0.007 0.013 0.002 0.010 0.002 0.008 0.028 -0.030*** 0.012 0.055*** -0.062*** -0.012* 0.020 -0.035** 0.051 -0.008 -0.003 0.017 -0.105*** -0.064*** -0.017 -0.036*** 0.212*** 0.008 0.009 0.009 0.010 0.006 0.013 0.015 0.036 0.031 0.007 0.012 0.002 0.011 0.017 0.007 0.027 0.917*** 0.029 0.984*** 0.026 20,104 19,229 100.919*** .159 126.208*** .198 significant at ***1% level, **5% level, *10% level 30 Chart A: Two Year Survival Rates (%) Chart B: Conditional Closure Rates (%) By data source Six months to... 100.0 14 12 80.0 10 8 60.0 6 40.0 81.8 69.3 67.0 73.3 20.0 4 2 VAT Barclays (account) Barclays (fi rm) Dataset 0 6 0.0 VAT Barclays (account) Barclays (firm) 12 18 Dataset source: DT I, Barclays 24 30 36 months since start-up source: DTI, Barclays Chart C: Volatility Distribution % of surviving firms, periods 1 & 4 3 peri od 1 peri od 4 2 1 0 low high volatility so urce : Ba rcla ys 31