Document 12461788

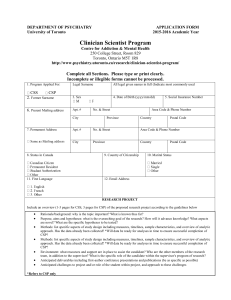

advertisement