Regulatory Reform in the Wake of the Financial Crisis of 2007—2008

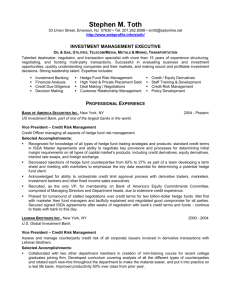

advertisement