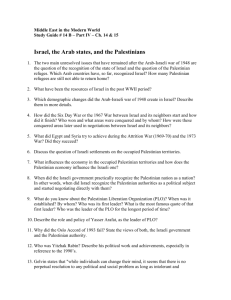

The Logic of Israel's Targeted Killing

advertisement

The Logic of Israel's Targeted Killing by Gal Luft Middle East Quarterly Vol.10, No.1 (Winter 2003) http://www.meforum.org/article/515 Israelis dislike the term "assassination policy." They would rather use another term— "extrajudicial punishment," "selective targeting," or "long-range hot pursuit"—to describe the pillar of their counterterrorism doctrine. But semantics do not change the fact that since the 1970s, dozens of terrorists have been assassinated by Israel's security forces, and in the two years of the Aqsa intifada, there have been at least eighty additional cases of Israel gunning down or blowing up Palestinian militants involved in the planning and execution of terror attacks. Many critics view this mode of operation as operationally senseless and illegal. It is deemed to be operationally senseless because assassinating Palestinian militants only brings harsh retaliatory action, resulting in even more Israeli casualties. They regard it as illegal, since it infringes on the sovereignty of foreign political entities and because it gives the security services discretion to decide on the killing of certain individuals without due process. Most important, claim the critics, there is no compelling evidence the killings are effective in reducing the terror menace. This is exactly where they have it wrong. True, terror persists despite the assassinations, and the policy does have shortcomings. What is less apparent is the profound cumulative effect of targeted killing on terrorist organizations. Constant elimination of their leaders leaves terrorist organizations in a state of confusion and disarray. Those next in line for succession take a long time to step into their predecessors' shoes. They know that by choosing to take the lead, they add their names to Israel's target list, where life is Hobbesian: nasty, brutish, and short. Fighting terror is like fighting car accidents: one can count the casualties but not those whose lives were spared by prevention. Hundreds, if not thousands, of Israelis go about their lives without knowing that they are unhurt because their murderers met their fate before they got the chance to carry out their diabolical missions. This silent multitude is the testament to the policy's success. Chronicle of Targeting Israel has traditionally resorted to assassination as a reaction to mounting waves of Palestinian terror activity. The first wave of terrorism occurred in the 1970s with a series of airliner hijackings, attacks on Israeli targets abroad (including the massacre of eleven Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics), and cross-border infiltrations of terrorists from Lebanon. This initial wave resulted in heavy casualties, demoralizing Israeli society. Since the infrastructure of Palestinian terror groups was located mainly in host Arab countries, all of them in a state of war with Israel, extradition or other forms of coordinated legal action against the terrorists were not options. The only way to retaliate against them was by targeting the perpetrators and the masterminds. The long arm of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), the General Security Service (GSS), and the Mossad often reached and surprised terrorists in the most remote locations. In one attack, in April 1973, Israeli commandos led by Ehud Barak—who dressed as a woman—landed in Beirut and killed senior members of the Fatah movement including Yasir Arafat's deputy Yusuf Najjar and the Fatah spokesman Kamal Nasir. Israel also stood, allegedly, behind the 1979 explosion in Beirut that killed Hasan ‘Ali Salamah, founder of Fatah's elite Force 17. Another spectacular operation took place a decade later in April 1988 when an Israeli commando force under the command of today's IDF chief of staff Moshe Ya‘alon landed in Tunis and killed the head of the Palestine Liberation Organization's (PLO) military branch, the second in seniority in the organization, Khalil al-Wazir (Abu Jihad). Apart from settling the score with Abu Jihad, who was responsible for many bloody terror attacks, Israel sought to weaken the PLO leadership, believing that such a blow would help quell the intifada that had erupted five months earlier. The attempt to influence strategic developments by means of an isolated military strike failed, and the intifada continued for another five years.[1] The signing of the 1993 Oslo agreement changed Israel's approach to the PLO from an adversary to a peace partner. Consequently, Israel ceased military action against PLO activists and unofficially pardoned those known as terrorists in the pre-Oslo era. Nevertheless, the targeting of members of terror organizations opposed to the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, such as Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), continued with even greater intensity. In October 1995, following a series of suicide attacks which claimed the lives of dozens of Israelis, Mossad agents shot and killed the head of the PIJ, Fathi Shiqaqi, in Malta. Three months later, Hamas member Yahya ‘Ayyash, also known as "The Engineer," who masterminded suicide attacks in which fifty Israelis died and 340 were wounded, took his last phone call when a booby-trapped cellular phone exploded in his hands. In addition to targeting Palestinian terrorists, Israel also used the assassination policy in its war against the Shi‘ite movements Hizbullah and Amal in southern Lebanon. Hizbullah is one of the most secretive and intricate guerrilla movements in existence. The discreet and small makeup of its military branch—only a few hundred strong—made penetration of its ranks difficult. Nevertheless, over the eighteen years of its occupation of south Lebanon, Israel succeeded in targeting several key military leaders of Hizbullah and Amal. The most significant operation took place in February 1992 when Israeli helicopters fired missiles at the car of Hizbullah's leader, ‘Abbas Musawi, killing him and members of his entourage. Amal's operations officer, Hussam al-Amin, was killed in a similar way in August 1998. With the outbreak of the Aqsa intifada in September 2000 and the release from Palestinian jail of some eighty Hamas and PIJ prisoners—all serving sentences for their involvement in terror attacks—the Palestinian Authority (PA) abdicated its responsibility to fight and prevent terrorism. To make things worse, the Tanzim, the armed militia of Arafat's Fatah movement, took a leading role in the armed struggle against Israel, involving itself in hundreds of shooting and suicide attacks against Israeli civilian targets. In the absence of security cooperation with the Palestinian security services, Israel stood alone against a mounting wave of terror. In the twelve months that followed, there were at least forty cases of assassinations of middle- and high-level Palestinian activists. Nineteen of them belonged to Hamas, nine to the PIJ, twelve to the Tanzim and Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, and two to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). The first took place on November 9, 2000, near the West Bank town of Bethlehem, when an Israeli Apache helicopter fired a laser-guided rocket at the vehicle of a Tanzim leader, Husayn ‘Abayat, killing him and wounding his deputy. The same mode of operation was repeated on February 13, 2001, against Mas‘ud ‘Iyyad, a Force 17 officer trying to establish a Hizbullah cell in the Gaza Strip, and against PIJ activist Muhammad ‘Abd al-‘Al, who according to the IDF was responsible for terrorist acts and was on his way to carry out two major attacks. The use of attack helicopters to intercept terrorists in Palestinian-controlled territories—or "Area A" as it appears in the Oslo agreements—proved to be precise and effective. The main downside of helicopter attacks was that such operations did not allow Israel any deniability. For this reason, Israel claimed responsibility for all helicopter assassinations while remaining mute in most cases in which activists were gunned down in the middle of the street or by long-range sniper bullet. Prime Minister Ariel Sharon explained: Sometimes we will announce what we did, sometimes we will not announce what we did. We don't always have to announce it.[2] And indeed, there have been several cases of activists being killed when the car they drove mysteriously blew up. In another incident, on April 5, 2001, a member of the PIJ who learned from ‘Ayyash's mistake in using a cellular phone, was killed when the phone booth he regularly used blew up. There were also other unexplained accidents. Israel never claimed responsibility for these killings, but the sophisticated technology involved, such as unmanned aerial vehicles, surveillance, and voice recognition devices, left little doubt that its hand was at work. Then, on July 22, 2002, in what was referred to by Sharon as "one of our greatest successes," Israel ascended another rung in the ladder of escalation, using a one-ton bomb dropped from an F-16 fighter jet to kill Salah Shihada, the leader and founder of Hamas' military wing of ‘Izz adDin al-Qassam in Gaza. Shihada was one of the most senior activists to be targeted since the outbreak of the intifada. The organization under him was responsible for fifty-two attacks on Israeli targets, killing a total of 220 Israeli non-combatants and sixteen soldiers. Despite that, the assassination drew heavy criticism by the international community when the bomb killed fifteen civilians, including nine children. The Debate It was not Shihada's killing but one prior, that of a West Bank dentist, Thabit Thabit, on December 31, 2000, which sparked the debate both in Israel and abroad regarding the morality, legality, and effectiveness of assassinations. There was something about Thabit's resume that made people suspect that he was somewhat less than the classic profile of a terrorist who merited the death penalty. Perhaps it was his age, forty-nine; his record as a human rights activist; his job as director general of the Palestinian health ministry; or his wide social circle of friends in the ranks of Israel's Peace Now movement, all of whom attested that he was a staunch supporter of the peace process. The IDF fought back, deploying its chief of operations, Giora Eiland, to explain in a 60 Minutes interview that "Dr. Thabit was, in fact, Dr. Hyde," and that behind the mask of a peaceloving dentist lurked a dangerous Fatah activist involved in many terrorist activities. The General Security Service released information obtained in the interrogation of a Palestinian suspect, showing that Thabit had been a regional commander with authority over units of Palestinian gunmen in the Tulkarem area.[3] Thabit's wife petitioned the Israeli high court of justice to order the government to stop its policy of assassinations. The unprecedented petition presented the Israeli judicial system with the controversial question of whether the assassination policy is in accordance with the law of nations. On its face, international law prohibits assassinations both in times of peace and in times of war. Furthermore, infringement on the sovereignty of other nations, especially by the imposition of extrajudicial punishment on their citizens, is a gross violation of international law. But the law also specifies that countries should not allow their territory to be a safe haven for terrorists who might bring harm to another country, since terrorists are considered to be common enemies of humankind, and that sovereign countries should prosecute them regardless of their agendas.[4] In Israel's case, the situation is far more complicated. The PA has not been declared a state, and, therefore from a legal point of view, is not bound by the set of norms, rules, and treaties with which most states comply. But those few treaties signed by the PA—the Oslo and Cairo agreements and the Wye River and Sharm al-Sheikh memoranda—underscored the Palestinian responsibility to fight terrorism using its twelve-branch security apparatus, created and assisted by Israel and U.S. Central Intelligence (CIA) to do just that. The PA has not only failed to do so, it has released terrorists from prison and supplied them with arms and funding. Furthermore, in many cases in which Israel gave the PA solid information about terrorist attacks in the making, the PA, instead of arresting the perpetrators, informed them that Israel knew of their plans.[5] In a legal opinion, Israeli attorney general Elyakim Rubinstein wrote: The laws of combat which are part of international law, permit injuring, during a period of warlike operations, someone who has been positively identified as a person who is working to carry out fatal attacks against Israeli targets, those people are enemies who are fighting against Israel, with all that implies, while committing fatal terror attacks and intending to commit additional attacks—all without any countermeasures by the PA.[6] This argument gained little sympathy abroad. Even Israel's closest ally, the United States, expressed its discontent with the practice. The official position of the Bush administration as conveyed by both White House and State Department spokesmen has been that "Israel needs to understand that targeted killings of Palestinians don't end the violence, but are only inflaming an already volatile situation and making it much harder to restore calm."[7] But if the United States showed signs of irritation in public, Israel's war against terror was received with understanding behind the scenes. Departing from the administration's position, Vice President Dick Cheney said in a television interview that he believed the policy of targeted killings could be justified: If you've got an organization that has plotted or is plotting some kind of suicide bomber attack, for example, and they have evidence of who it is and where they're located, I think there's some justification in their trying to protect themselves by preempting.[8] Administration officials rushed to explain that they had "a consistent view" of Israeli targeted attacks, and that the "administration at all levels deplores the violence there and that includes the targeted attacks."[9] But Israel was never deterred by Washington's expressed reservations. Matan Vilnai, Israeli science minister, responded in the summer of 2001 to U.S. criticism of the targeted killings: I would like to see how the Americans would react if a car packed with explosives blew up in the middle of Manhattan.[10] Two months later, not a car, but two jetliners blew up in lower Manhattan and with them all the reservations and inhibitions Americans had regarding their own fight against terrorism. A Newsweek poll taken three months after September 11 showed that nearly two-thirds of Americans polled approved of giving U.S. military and intelligence agencies the power to assassinate terrorist leaders in the Middle East; 57 percent approved of expanding targeted killings to Africa and Asia; and 54 percent thought assassinations should be carried out in Europe as well.[11] And indeed, the war in Afghanistan prompted the United States to make attempts on the lives of al-Qa‘ida activists as well as rejectionist Afghan leaders.[12] A U.S. missile also killed Yemen's top al-Qa‘ida commander. Additionally, it has also been reported that President Bush gave the CIA and U.S. special forces authority to use "lethal force" to kill the Iraqi president, Saddam Hussein.[13] Although Israel has gained more sympathy abroad for its tactic since September 11, not all Israelis are entirely convinced that the method is worth pursuing. Critics of the "selective targeting" policy point out its self-destructive aspect. After each targeting, the Palestinians promise—and in most cases deliver—a hard and painful response. Assassination victims are automatically hailed as martyrs, and vengeful Palestinian admirers of the deceased volunteer to take his place. Following ‘Ayyash's death, Arafat publicly proclaimed him a martyr and a hero; streets in Palestinian cities were named after him; and a wave of suicide bombings resulted in fifty-nine dead and 250 wounded Israelis. Following the January 2001 assassination of the Fatah leader in Tulkarem, Ra'd Karmi, the Tanzim and Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades claimed responsibility for attacks that took the lives of fifty-seven Israelis. Hizbullah is also a vindictive organization. ‘Abbas Musawi's killing was soon followed by the bombing of the Israeli embassy in Argentina. The price was heavy: twenty-nine killed and 242 wounded. Another drawback: assassinations of key political and military activists may invite similar attempts on the lives of Israeli leaders. The death of Abu-‘Ali Mustafa, secretary-general of the PFLP, assassinated in August 2001, prompted the killing two months later of Israeli minister of tourism Rehavam Ze'evi. Following the killing of Salah Shihada, a Palestinian militant group, the Popular Army Front–Return Battalions, responded by releasing a hit list of twenty prominent Israeli officials, with Prime Minister Ariel Sharon at the top.[14] Targeting Palestinian militants has put at risk thousands of IDF officers and their families who may become targets of Palestinian retaliatory action. This threat is not taken lightly in the IDF. For the first time in Israel's history, Israeli generals now have bodyguards assigned to them. However, many Israelis dismiss the argument that the killing feeds a vicious cycle of death and violence that might not be to Israel's benefit. They believe there is no causality between Israel's actions and the Palestinians' decision to embrace terror. "Islamic Jihad and others do not need excuses to carry out attacks," said Israel's former deputy defense minister Ephraim Sneh, "since in any case they are constantly trying to harm Israelis."[15] What is less obvious to the critics is the number of attacks that have been thwarted through the masterminds' removal. "Ticking bomb," a well-known term in counterterrorism jargon, refers to a terrorist or a group of terrorists in the process of launching an attack. Killing the perpetrator or his dispatcher stops the clock. The Karmi assassination was undertaken to prevent him from carrying out his plans, which included the assassination of a prominent Israeli. ‘Umar Sa‘adah, the head of the Hamas military wing in Bethlehem, killed in July 2001, was planning a major attack at the closing ceremony of the Maccabiah Games, the Jewish olympics. [16] At the time of his assassination, Salah Shihada was in the process of organizing a "mega-attack" of six terror operations that were to take place simultaneously.[17] Nobody will ever know the scope of the bloodbath that was prevented by thwarting these attempts. These acts never made headlines; they constitute the silent terror—the terror that never happened. Political Risks Targeted killing is a risky business, especially when missions fail, and they often do. The outcome in such cases is operationally damaging, and some blundered attempts have entangled Israel in a diplomatic morass. In 1973, for example, a Mossad team in Lillehammer, Norway, on a mission to assassinate a PLO leader, mistakenly targeted an innocent restaurant waiter and caused an unpleasant diplomatic incident between Israel and Norway. Worse, in September 1997, two Mossad agents were captured in Amman after attacking a Hamas leader, Khalid Mash‘al, with a high-tech device intended to poison him. Mash‘al's life was saved after he was treated with an antidote demanded of the Israelis by the furious King Hussein. The failed attempt was not only a blow to the Mossad's impeccable image but also to fragile Israeli-Jordanian relations. It occurred during one of the low points of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process during the short term of the rightwing government of Binyamin Netanyahu. To ease the king's wrath over Israel's violation of Jordanian sovereignty, Netanyahu himself secretly traveled to Jordan, but King Hussein refused to meet with him, sending his crown prince instead. Subsequently, a deal was reached to spare the two Mossad agents from trial in Jordan by exchanging them for Hamas founder Sheikh Ahmad Yasin, imprisoned in Israel. The assassination attempt meant to weaken the leadership of Hamas instead ended up achieving exactly the opposite result. To make things worse, Israel also found itself involved in an embarrassing diplomatic incident with the government of Canada. It was discovered that the Mossad tried to cover its tracks by equipping Mash‘al's assassins with forged Canadian passports. The Mash‘al case is a good example of the risks involved in assassination attempts carried out in foreign countries. The short-term gain derived from a successful operation can be easily offset by the severe damage to long-term diplomatic relations in the case of a blunder. Another problem of a systematic targeting campaign is that Israel's actions have become a widely used cover for domestic killings among Palestinians. Many of the feuds and tensions in the divided and highly corrupt Palestinian security establishment are handled violently. Blaming Israel for the murder of every security leader, terrorist, or any other visible figure has become a conditioned reflex among Palestinians. When a powerful car bomb exploded in March 1998, killing one of ‘Ayyash's disciples, Muhi ad-Din ash-Sharif, one of Israel's most wanted terrorists, a finger of blame was automatically pointed at Israel. Only later was it discovered that the killing was a result of internal rivalries among various factions of Hamas. Arafat blamed Israel for killing his confidant Hisham Makki, director of Palestinian television, shot point blank by three assassins in Gaza.[18] Palestinian television hurried to blame the "dark forces of the occupation" for Makki's death, only later to learn the assassination was carried out by the forces of what was then a nascent Palestinian organization called Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades.[19] To Terrorize a Terrorist Despite the shortcomings of the current policy, there is nearly a consensus among Israel's defense officials that it is the most effective and least injurious way to deter and prevent terrorist groups from perpetrating terror attacks, especially in light of the PA's refusal to fight terror. Officials believe that despite occasional mistakes causing the death of innocent civilians—in the first twenty-two months of the intifada, forty-four Palestinian bystanders were killed in the process of targeted killings—any alternative tactic would inflict much more harm to innocent civilians. To assess the real impact of targeted killing on the infrastructure of terrorist groups, one needs to understand their organizational culture, psychology, and behavior. The operational branches of organizations such as Hamas or the PIJ consist of three layers: political-military command, intermediate level, and what can be referred to as the "ground troops." The political-military command echelon—most of which is in the Gaza Strip—consists of a small group, no more than a dozen activists, responsible for funding, political and spiritual guidance, and direction of the organization's strategy. They maintain regular contact with the headquarters of terrorist groups throughout the Arab world as well as with senior leaders of the PA and chiefs of its security forces.[20] The intermediate level of command is a group slightly larger in size, a few dozens in each Palestinian city. Its members are involved in planning operations, and recruiting, training, arming, and dispatching terrorists. The different cells are loosely connected, and their members do not usually operate outside their area of jurisdiction. Members of this group, especially those living in Gaza, meet frequently with the senior leadership and receive daily orders and funds to finance their operations. Unlike members of the first group, intermediate-level activists are not so familiar to the public, and their killing does not evoke the same rage as does the targeting of senior leaders. For this reason, Israel has so far preferred to target as few senior leaders as possible and focus on members of the second group. Israel has always believed that draining the swamp is more important than fighting the mosquitoes: the infrastructure of the terror organizations, those who initiate, plan, or facilitate terror attacks as well recruiters, dispatchers, and fundraisers are just as culpable as those who actually pull the trigger or detonate the bomb. Hence, members of the second group are considered "ticking bombs" even if they are not those who personally carry out the attacks. The ground troops are those recruited to be the actual perpetrators of either suicide operations or what Palestinians refer to as "martyrdom operations"—shooting attacks in Israeli population centers in which the probability of survival of the perpetrator is slim. These volunteers are recruited on an ad hoc basis and maintain contact only with their operators. In most cases they are not exposed to the organization's secrets and have very little knowledge about its structure and operations. Occasionally, due to technical malfunction or cold feet, suicide bombers fail in their mission and are captured alive by the Israeli authorities. A "dud" who breaks during interrogation and provides information on his (or her) dispatchers is a threat to the entire organization. As a result, some operators refrain from exposing their identity to their troops. They prefer to wear a mask or communicate with them indirectly through letters or by phone.[21] As a result, the nature of Palestinian terror organizations is that they are secretive and compartmentalized. People hardly know each other. There are no headquarters, files, computers, radio equipment, or organizational memory. Removing one activist can handicap or destroy an entire cell, but removal of one cell does not necessarily bring down the entire organization. Despite defiant Palestinian rhetoric, Palestinian activists' fear of being on Israel's target list is paralyzing, and that is exactly what Israel wants. Explained Sharon: The plan is to place the terrorists in varying situations every day and knock them off balance so that they will be busy protecting themselves.[22] While on the run, the Palestinian terrorist's energy is devoted to survival rather than to planning the next attack. The terrorist detaches himself from his close circle of friends and family and begins to live a fugitive's life. He is forced to spend each night in a different location, often sleeping in the open field. Hours each day are wasted looking for a safe haven to spend the coming night. Most difficult is the distance from his home and family. He knows that any contact with his wife or parents could cost him his life. Consequently, he is completely at the mercy of his confidants, not knowing which one of them might be an Israeli collaborator. Booby-trapped cars and telephones increase the feeling among Palestinian militants that the long arm of the Israeli security forces reaches their most intimate surroundings. They become nervous and suspicious of collaborators who might live among them. A Palestinian journalist conveyed the atmosphere of fear and confusion in the Palestinian street after Shihada's killing: People are now looking for wanted men. They are stopping them in the middle of the street and will now begin asking for their identification before they enter a specific residential neighborhood. … No one feels safe. … How do you know who will be Shihada number two, and where the missile will come from? … Someone must have told the Shin Bet (GSS) that Shihada was visiting his house; that someone must live among us, and now everyone is looking for collaborators.[23] And they should. Despite the deep animosity toward Israel, many Palestinians are still willing to face the risk of the death penalty the PA imposes on collaborators and provide valuable information to the Israelis. In a society where more than half of the families live below the poverty line, one can always find people willing to collaborate with the enemy in exchange for money or other benefits. Assassinations of military leaders are traumatic events in the lives of their organizations, often leading to a change in organizational behavior. Commanders become extremely suspicious and cautious. They leave few traces of their whereabouts; restrict information about operational planning to small groups of secret keepers; and recruit new members more selectively. The paranoid environment in which terrorists operate reduces their effectiveness drastically. Trust is the bedrock of any human activity, including terrorism. Without it, the organization becomes disjointed; information cannot be disseminated; people do not feel part of a team; lessons are not learned properly. Additionally, communication between the different cells breaks down. Following the killing of Musawi, Hizbullah squads began to maintain strict radio silence, preventing Israel from monitoring the organization's action. In the territories, Palestinian militants who fear Israeli eavesdropping refrain from using the telephone to communicate with each other. This leads to further confusion and misunderstandings. Such a dynamic has a cumulative, holistic, negative influence on the organization's effectiveness. The influence cannot be precisely measured or even assessed by empirical tools, but it is certainly profound. Thankless Counterterrorism is a shadow war carried out far from the public's eye. It is a war of prevention. Success is an uneventful day in which people go about their lives without being killed, maimed, or stunned by a blast. It is a war without celebrated victories: public consciousness is much better in recording those days in which prevention failed than those of normalcy. The soldiers of this war drive no tanks and fire no cannons. They search homes, operate surveillance equipment, recruit informers, and interrogate suspects. But no war is sterile, and at times the only weapon able to target the enemy's center of gravity is the hit man. Knowing that retaliation is inevitable, the decision to use this weapon is difficult and is taken by the highest authority in Israel only when it is probable that inaction will carry an even higher price. Israel is at war, and war, as Clausewitz wrote, has its own grammar.[24] Targeted killing, Israelis overwhelmingly believe, is still an essential part of their war's grammar. Gal Luft, a doctoral candidate at the Johns Hopkins University's Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, is the author of The Palestinian Security Forces: Between Police and Army (Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1998). [1] Moshe Zonder, Sayeret Matkal (Jerusalem: Keter, 2000), pp. 238-48. [2] Ha'aretz, (Tel Aviv), Apr. 6, 2001. [3] Ibid., Mar. 14, 2001. [4] "The International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism," U.N. General Assembly resolution 54/109, Dec. 9, 1999, at http://www.un.org/law/cod/finterr.htm; U.N. Security Council resolutions 1368 (2001) and 1373 (2001) at http://www.un.org/terrorism/sc.htm#reso. [5] Yedi'ot Aharonot (Tel Aviv), July 12, 2002. [6] Ha'aretz, Feb. 12, 2001. [7] Richard Boucher, State Department briefing, July 2, 2001, at http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/dpb/2001/4656.htm. [8] Fox News Special Report, Aug. 2, 2001, at http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,31241,00.html. [9] White House briefing, Aug. 3, 2001, at http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/briefings/20010803.html#some%20justification. [10] The Guardian, July 3, 2001. [11] Newsweek, Dec. 15, 2001. [12] USA Today, May 9, 2002. [13] The Guardian, June 17, 2002. [14] The Jerusalem Post, July 28, 2002. [15] Ibid., Dec. 12, 2000. [16] Ha'aretz, July 18, 2001. [17] The Jerusalem Post, July 30, 2002. [18] Ma'ariv (Tel Aviv), Apr. 6, 2001. [19] The Jerusalem Post, Jan. 18, 2000. [20] Based on author's discussion with Israeli intelligence sources. [21] Based on author's discussion with Israeli intelligence sources. [22] The New York Times, Apr. 12, 2001. [23] The Jerusalem Post, July 26, 2002. [24] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), pp. 100, 605.