14-19 Education and Training A Commentary by the Teaching and May 2006

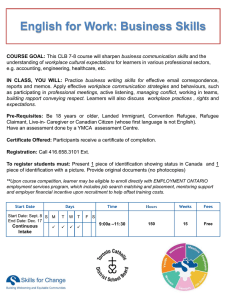

advertisement