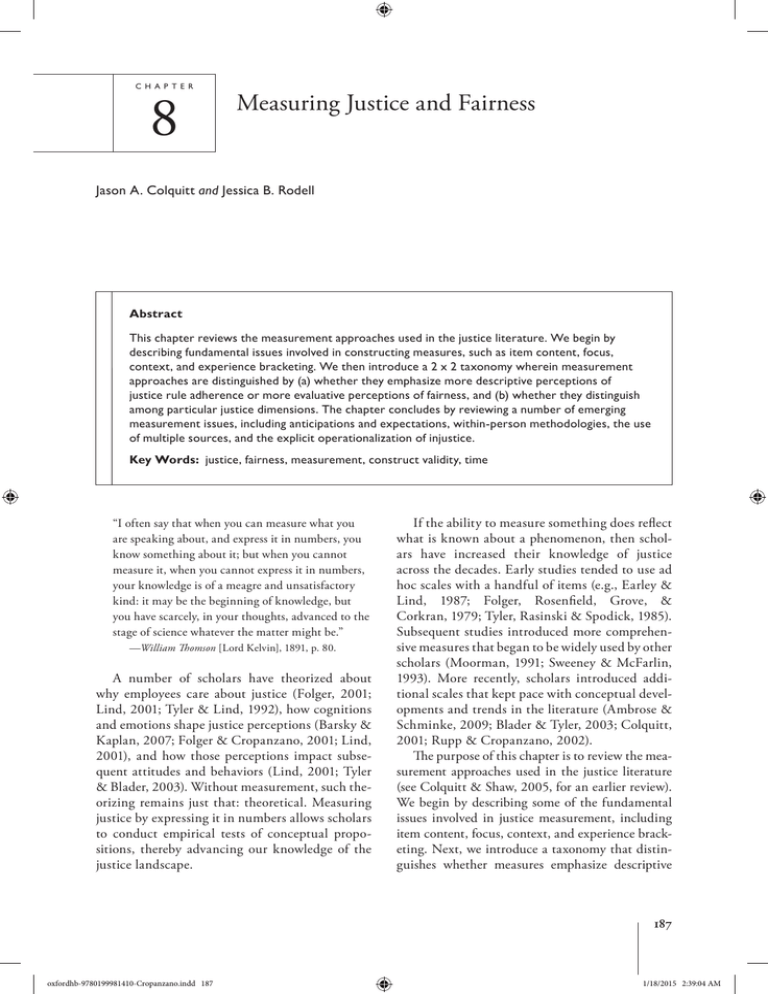

8 Measuring Justice and Fairness and

advertisement