6 The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit from

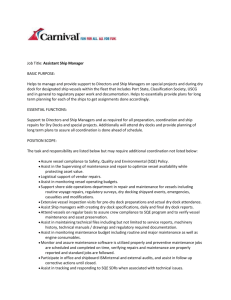

advertisement