Home Range and Habitat Utilization of Breeding Male Merlins, D BECKER

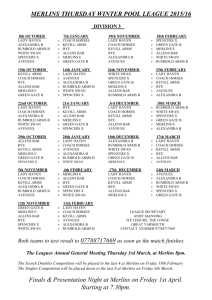

advertisement

Home Range and Habitat Utilization of Breeding Male Merlins, Falco columbarius, in Southeastern Montana DALE M. BECKER1,2 and CAROLYN HULL SIEG3 1 USDI Fish and Wildlife Service, Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana 59812 2 Present Address: USDI Bureau of Indian Affairs, Flathead Agency, Box A, Pablo, Montana 59855 3 USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, South Dakota School of Mines Campus, Rapid City, South Dakota 57701 Becker, Dale M., a n d Carolyn H columbarius, in southeaster 1 Sieg. 1987. Home range and habitat utili zation of breeding male Merlins, Falco Monta na. Canadian Field-Naturalist 10l(3): 398-403. Home range size and habitat utilization of three breeding male Richardson’s Merlins (Falco columbarius richardsonii) in 2 southeastern Montana were studied using radio telemetry. Home ranges of these birds encompassed 13,23, and 28 km . Each bird traveled up to 9 km from its nest. Each home range encompassed five habitats; sagebrush/grassland, riparian, and Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa) communities were used significantly (p 5 0.05) more, and grasslands and agricultural fields less (p 5 0.05), than expected, based on the proportions in the combined home ranges. Four sites regularly used by hunting male Merlins indicated preferences for patchy shrub/grasslands as hunting habitats. Key Words: Merlin, Falco columbarius, home range, habitat, southeastern Montana. Richardson’s Merlin (Falco columbarius richardsonii) is an inhabitant of sparsely treed grasslands in the northern Great Plains. Breeding pairs in Canada nest in small groves of deciduous trees along rivers (Bent 1938) and shelterbelts adjacent to grasslands (Hodson 1976). In the western United States, Richardson’s Merlins nest in deciduous riparian communities (Call 1978) and in coniferous stands in close proximity to grasslands (Ellis 1976; Becker 1984). Previous food studies in these areas suggest that Richardson’s Merlins hunt in grassland habitats (Bent 1938; Fox 1964; Hodson 1976); however, detailed information on habitat utilization and home ranges of these birds is lacking in the literature. The objectives of this study were to determine the size of home ranges of male Merlins and to identify preferred hunting habitats. Males were selected for study because they do most of the hunting for the breeding pair and nestlings. Study Area The 39 448-ha study area in southeastern Montana consisted largely of sagebrush/ grassland shrubsteppe and agricultural fields interspersed with buttes and rolling hills dominated by stands of Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa). Maximum elevation is 1282 m above sea level. The climate is characterized by hot summers, cold winters, and a semi-arid moisture regime. Annual precipitation averages 39 cm, of which 70% falls from May through 398 September. Monthly mean temperatures during the Merlin breeding season range from -8 o C in March to 33oC in July. Methods Adult male Merlins were captured near their nest sites in late May and early June of 1980. To minimize disturbance of breeding adults near their nests, capture was attempted only after young had hatched. A dho-gazza trapping device was modified from that described by Beebe and Webster (1964), and a permanently crippled Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) was used to lure the Merlins into mist nets. After capture, the Merlins were restrained in a stocking while the transmitters were being attached. Each of the three male Merlins captured was fitted with an SM-1 transmitter manufactured by the AVM Instrument Company 1 The transmitter package weighed approximately 7 g, or approximately 4 % of the bird’s weight. It was attached ventrally to the proximal end of the shaft of a central tail feather by two strands of monofilament embedded in the dental acrylic covering of the transmitter package. Antennas 1987 BECKER AND SIEG: HOME RANGE AND HABITAT OF MALE MERLINS 401 TABLE 2. Percent bare ground, litter cover, and plant canopy cover of major plant species on four sites where male Richardson’s Merlins were frequently observed hunting in southeastern Montana. Site number Cover Type 1 2 3 4 BARE GROUND 42.5 18.9 18.4 9.3 LITTER S HRUBS Silver Sagebrush, Artemisia cana Fringed Sagebrush, A. frigida Big Sagebrush, A. tridentata Plains Pricklypear, Opuntia polyacantha Woods Rose, Rosa woodsii Western Snowberry, Symphoricarpos occidentalis 1 OTHERSHRUBS GRASSES Western Wheatgrass, Agropyron smithii Blue Grama, Bouteloua gracilis Buffalograss, Buchloe dactyloides Sandberg Bluegrass, Poa secunda 2 Other grasses FORBS Common Y arrow, Achillea millefolium 3 Other forbs 8.9 16.4 19.8 29.6 0.6 19.3 1.1 0.1 11.7 0.7 1.1 7.4 0.6 O THER Lichen, Parmelia chlorochrae Club Moss, Selaginella densa Algae 10.4 0.2 1.2 16.3 1.0 1.0 1.3 6.4 2.1 1.3 0.5 1.0 2.6 13.7 5.3 8.2 2.0 1.1 1.3 2.3 1.0 1.9 5.3 2.6 16.1 0.5 1.0 2.2 26.4 2.5 1.0 1.9 2.5 10.6 0.8 1 Gardner Saltbush (Atriplex gardneri), Broom Snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae). Tumblegrass (Schedonnardus paniculatus), Needle and thread (Stipa comata). Small-leaf Pussytoes (Antennaria parvifolia), thistle (Cirsium sp.), Scarlet Gaura (Gaura coccinea), Silky Crazyweed (Oxytropis sericea), Fuzzytongue Penstemon (Penstemon eriantherus), Scurfpea (Psoralea sp.), Field Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense), Hoods Phlox (Phlox hoodii). 2 3 (Table 2). Site 3 was dominated by Big Sagebrush and Western Wheatgrass. Each of these three sites were in the sagebrush/grassland habitat. Site 4 was in the riparian habitat, and was dominated by Western Snowberry and Western Wheatgrass. Shrub densities in the three sagebrush/ grassland sites were variable, ranging from 7530 to 14740 stems/ ha of Big Sagebrush and Gardner Saltbush (Atriplex gardneri) (Table 3). The riparian site had a total shrub density of 43350 stems/ha. Average maximum vegetation height was also variable, averaging 16.6 cm on the three sagebrush/grassland sites, and 44 cm on the riparian site. Discussion Few comparative data on home range sizes or foraging distances of breeding Merlins are available. Hodson (1976) concluded from behavioral observations that breeding Merlins in Alberta hunted up to 1.6 km from their nesting sites. The home ranges of the Montana Merlins and maximum distances they traveled from their nests were considerably larger. Richardson’s Merlins have longer wings and tails and lighter wing-loading in comparison with other subspecies of Merlins inhabiting forested habitats. These physical differences may be adaptations that allow this subspecies to range over large areas (Temple 1972). Other factors involved in these differences may have included differences in habitats within home ranges, terrain, prey availability and abundance, or some combination of these factors. Results of this study indicated a high degree of use of sagebrush/ grassland habitats by hunting male Merlins during June and July. A study of food habits of this population of Merlins indicated that Horned Larks (Eremophila alpestris), Lark Buntings (Calamospiza melanocorys), and Vesper Sparrows (Pooecetes gramineus) constituted 27%, 18%, and 13% of 427 food items, respectively (Becker 1984). Merlin use of sagebrush/grassland may have been a 402 T HE CA N A D I A N TABLE 3. Shrub densities (stems/ ha) at four sites where hunting male Richardson’s Merlins were frequently observed in southeastern Montana. Shrub densities (stems/ ha) Site number Species Big Sagebrush Western Snowberry Silver Sagebrush Woods Rose Gardner Saltbush Totals 2 3 14740 7 110 4470 - 35 5 - 2 420 20 14 740 7 530 4 490 43 4 130 590 540 090 350 direct result of relatively high densities of Horned Larks and Vesper Sparrows drawn to food, cover, and elevated perches provided by Big Sagebrush interspersed with grassland. Male Merlins were observed less often in grasslands than expected, based on availability of this habitat. In contrast, food habits of breeding Merlins in southeastern Montana indicated that birds typically associated with open grassland habitat were heavily preyed upon (Becker 1984). Similar results have been reported by Fox (1964) and Hodson (1978) for Merlins in Canada. The importance of the grassland habitat in our study, as represented by the number of radio locations in it, may have been underestimated because of a lack of elevated hunting perches in the form of shrubs or because of difficulty in locating Merlins perched on the ground in broken terrain. Thus, grassland habitat may be more important to hunting Merlins than indicated by the data presented. The limited use of agricultural habitat by adult male Merlins might have been influenced by a lack of perching sites, difficulty in locating Merlins on the ground, or by lower vegetation diversity and a corresponding lower density of potential prey species. In a study of avian habitat use in central North Dakota, Horned Larks and Vesper Sparrows were two of the most common species observed in croplands; however, of all major habitats sampled, croplands had the lowest breeding bird populations (Faanes 1982). The limited use of croplands by breeding birds was further illustrated by lower species richness, mean density, and species diversity in the North Dakota study. Higher than expected use of riparian habitats by hunting male Merlins was attributed mainly to the presence of water and food sources that attracted prey species. Also, shrub cover in this habvitat likely provided perches for both Merlins and their prey. The Ponderosa Pine habitat probably is not an important hunting habitat for Richardson’s Merlins. F I E L D -N ATURALIST Vol. 101 Forest avifauna constituted only 7% of food items identified for this population of Merlins (Becker 1984). However, because nests of the three Merlins in this study were in Ponderosa Pine stands, the birds spent considerable time at or near nest sites between hunting forays. The patchy shrub cover on four sites regularly used by hunting male Merlins likely provided cover, nesting sites, and perches for prey species. The variety of plant species on these sites may also have provided excellent food sources for passerines. In addition, small depressions in the ephemeral stream bed on the riparian site held water during the entire study period, and was likely important in attracting prey species. Although shrub density was highly variable on sites where Merlins were regularly observed hunting, it appeared that the presence of some shrubs increased the use of the site by Merlins. Shrubs were probably important to resident birds for elevated singing perches, as well as for hiding and nesting cover. The high variability in shrub densities and heights likely contributed to a diverse prey base. For example, Horned Larks make greater use of sites with low shrub densities, whereas Lark Buntings and Vesper Sparrows are more apt to utilize sites with intermediate to higher shrub densities (Johnsgard 1979). The results of this study indicated that Merlins used diverse habitat and prey; however, they relied most heavily on the abundant avifauna of sagebrush/ grasslands of the shrub-steppe. Management activities that would maintain or increase the natural diversity of these habitats would be beneficial to both Merlins and their prey. Removal of shrubs or conversion of sagebrush/ grassland habitat to agricultural cropland could reduce the quality of Merlin hunting habitat. The importance of the Ponderosa Pine habitat on the study area was clearly indicated by the Merlins’exclusive use of this habitat for nesting (Becker 1984). The pine community also provided important perching and roosting sites. Thus, management efforts in the area should be aimed at maintaining Ponderosa Pine and adjacent sagebrush/ grassland habitats. Acknowledgments We gratefully acknowledge assistance with field work by D. W. Carney and R. LeVesque. C. M. Anderson, I. J. Ball, M. R. Fuller, and C. W. Servheen provided critical review of earlier drafts of the manuscript. Funding for the study was provided by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station at Rapid City, South Dakota. 1987 BECKER AND SIEG H O M E R ANGE Literature Cited Becker, D. M. 1984. Reproductive ecology and habitat utilization of Richardson’s Merlins in southeastern Montana. M.Sc. thesis, University of Montana, Missoula. 62 pp. Beebe, F. L., and H. M. Webster. 1964. North American falconry and hunting hawks. World Press, Inc., Denver, Colorado. 314 pp. Beetle, A. A. 1970. Recommended plant names. Agricultural Experiment Station Research Journal 31. University of Wyoming, Laramie. 124 pp. Bent, A. C. 1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey. Volume 2. United States National Museum Bulletin 170: 70-83. Call, M. W. 1978. Nesting habitats and surveying techniques for common western raptors. Technical Note TN-3 16. United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Denver, Colorado. 115 pp. Daubenmire, R. 1959. A canopy coverage method of vegetational analysis. Northwest Science 33: 43-65. Ellis, D. H. 1976. First breeding records of Merlins in Montana. Condor 78: 112-I 14. Faanes, C. A. 1982. Avian use of Sheyenne Lake and associated habitats in central North Dakota. Resource Publication 144. United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. 24 pp. AND H ABITAT OF MALE MERLINS 403 Fox, G. A. 1964. Notes on the western race of the Pigeon Hawk. Blue Jay 22: 140-147. Hodson, K. A. 1976. The ecology of Richardson’s Merlins on the Canadian prairies. M.Sc. thesis. University of British Columbia, Vancouver. 83 pp. Hodson, K. A. 1978. Prey utilized by Merlins nesting in shortgrass prairies of southern Alberta. Canadian FieldNaturalist 92: 76-77. Johnsgard, P. A. 1979. Birds of the Great Plains: breeding species and their distribution. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 539 pp. Mohr, C. 0. 1947. Table of equivalent populations of North American small mammals. American Midland Naturalist 37: 223-249. Neu, C. W., C. R. Byers, a n d J. M. Peck. 1974. A technique for analysis of utilization-availability data. Journal of Wildlife Management 38: 541-545. Temple, S. A. 1972. Systematics and evolution of the North American Merlins. Auk 89: 325-338. Received 6 November 1985 A c c e p t e d 24 August 1987