What Do We Know About Corporate Headquarters? A Review, Integration, and Research Agenda

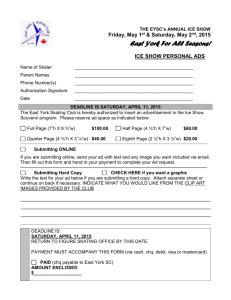

advertisement