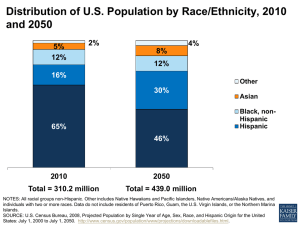

U.S. Population Projections: 2005–2050 Report Jeffrey S. Passel and D’Vera Cohn

advertisement