A Primer on the Restaurant Meals Program in California

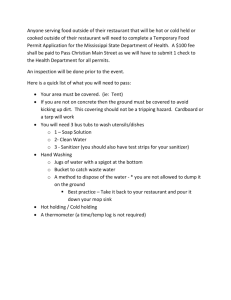

advertisement