The Private Politics Market David P. Baron June 5, 2014 Stanford University

advertisement

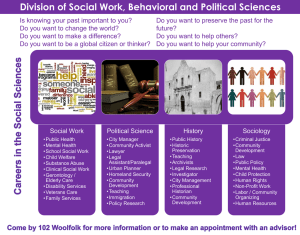

The Private Politics Market David P. Baron Stanford University June 5, 2014 Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 1 / 59 Introduction Introduction • Private politics is the use of social pressure to change the behavior of private economic agents. • Social pressure is strategically-directed by activists using an NGO as the vehicle • Activists are the agents of donors (and possibly the public) • The targets are typically firms that are associated with a social issue • The encounters between activists and firms have traditionally been confrontational • Predecessors • Social movements–emancipation, civil rights, revolution–typically directed at government • Unionization–directed at governments and firms • Focus here is on strategic activism and its targets • At the center of this is a campaign, which can be thought of as an "institution" of private politics Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 2 / 59 Introduction A Brief (U.S.) History of Strategic Activism • Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was perhaps the beginning • Campaigns against Apartheid and Nestle (infant formula) • The focus of activists was government–with considerable success • Laws enacted in the 1970s are broad and powerful • Government subsequently became blocked • Those bearing the costs of government policies became better organized and effective • Activists turned to the private sector. Michael Brune, head of the Rainforest Action Network, "We felt we could create more democracy in the marketplace than in the government." • Corporate campaigns against firms doing "bad" expanded rapidly, particularly after Brent Spar • At about the same time EDF invited McDonald’s to join in a project to reduce the company’s behind-the-counter waste; e.g., packaging • Gwen Ruta of EDF: "At the time, it was heresy to say that companies and NGOs could work together; now it is dogma, at least for the Fortune 500." (The Economist, June 5, 2010) Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 3 / 59 Introduction A Brief (U.S.) History of Strategic Activism (continued) • Some firms were difficult to influence through direct targeting, so activists innovated with market campaigns • Activists began targeting the supply and distribution chains of the firms doing bad • This exposed a huge new set of firms to the threat of activism: retailers, banks, suppliers, ... • Target Home Depot to stop selling lumber from old growth timber • Target Citigroup to stop providing project finance for harmful infrastructure projects in developing countries (the Equator Principles arose from the pressure on Citigroup and European banks) • Many of the targeted firms were doing no direct bad and viewed themselves as "innocent", but the threat was real • Corporate and particularly market campaigns resulted in a surge in self-regulation to avoid targeting • Self-regulation example: Under pressure from activists supporting the FSC, the U.S. timber industry formed the SFI. • The mantra of corporate social responsibility accelerated at about the same time • Cooperation between firms and NGOs became common Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 4 / 59 Introduction What is to be explained? • The outcomes of campaigns • When and why do campaigns occur on the equilibrium path? • What factors affect the outcome? • Do activists target soft or hard firms? • Do activists moderate their demands in private politics? • When do firms self-regulate and to what extent? • Why was there a surge in corporate social responsibility? • Why so much cooperation between NGOs and firms? • Two explanations • Expertise • Implementation of self-regulation • Which firms cooperate and which incur campaigns and why? • What governs the supply of strategic activism and private politics? Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 5 / 59 Introduction Alternative Explanations for Self-Regulation • (at least) Two alternative explanations • Morally motivated self-regulation (Baron (AER 2010), (JEMS 2009)) • There is certainly some of this, but how much? • Self-regulation induced by consumer demand • Firms simply compete for customers with social preferences • Firms produce "green" products, but is this is any different from any other response to consumer demand? • Focus here is on self-regulation due to social pressure; not demand • Demand effects are accommodated by the model • Endorsements by NGOs may affect demand, but their main effect may be in building a shield. • The perspective is that self-regulation is an attempt to shield a firm from harm arising from social pressure • Harm can be thought of as damage to brand equity, reputation, employee morale, supply and distribution relationships, etc. • This is hard to measure, but firms believe it is very important Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 6 / 59 Introduction Perspective • Firms are large and most NGOs are not • Where does the power lie? • Firms have disadvantages (perhaps disadvantages they earned) • Most important is the "trust gap"–people trust NGOs much more • • • • • than they trust firms The media reflect this trust gap Firms have difficulty communicating effectively with the public Reputations are hard to build and harder to maintain: "Three good media mentions" are wiped out by one "one bad media mention." The social cost of self-regulation is hidden in prices So, NGOs and activists are viewed as having power–the power to initiate and conduct effective private politics Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 7 / 59 Introduction The Trust Gap Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 8 / 59 Introduction Preview of Results • (Ex post) campaign success is decreasing in the residual harm to the target and its cost and increasing in the campaign scale • A strategically designed campaign has a probability of success of 21 • Targets can self-regulate to forestall campaigns, but self-regulation can be too costly • Principled demands can lead to campaigns on the equilibrium path, whereas strategic demands result in forestalling self-regulation • Strategic activists moderate their demands • Cooperative activists engage CSR firms; confrontational activists target profit-maximizers • Soft firms are more likely to be targeted than hard firms • The threat of social pressure is the principal factor in the success of private politics • There is a degree of safety in numbers • The supply of private politics is determined by donors • The surge in cooperation could be due to firms seeking a shield against confrontational activists • Two explanations for the surge in CSR • To obtain a shield from a cooperative activist (WWF) • A label for social pressure-induced self-regulation Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 9 / 59 Introduction Outline • Introduction • Confrontation and campaigns • The market for cooperation • Linkages among NGOs and preferences–an online experiment • Self-regulation • The market for activism • Presentation follows a line of thought through 4 papers: • "The Industrial Organization of Private Politics," 2012. Quarterly Journal of Political Science. • "Self-Regulation in Private and Public Politics," 2014. Quarterly Journal of Political Science. • "The Market for Activism," 2013. • "Extending Nonmarket Strategy: The Radical Flank Effect in Private Politics," 2013. (with Hugaveera Rao and Margaret Neale) Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 10 / 59 Introduction The Private Politics Market The Private Politics Market Funding Confrontation Threatened Cooperation Firm Donor Firm Resolution Forestalled Self-regulation Activist Campaign Firm Donor Activist Donor Cooperative activist Activist Donor Baron (Stanford University) Engagement Firm Firm NGO Conference Campaign Campaign June 5, 2014 11 / 59 A Campaign A Campaign • Activists demand that a firm change its policy to xA • The demand xA can be principled (exogenous) or strategic • If the campaign succeeds, the outcome is xA • Policy x o maximizes profit π (x ); decreasing in x for x ≥ x o . • π (·) could include demand-side rewards • Let the self-regulation policy of the firm be x ≥ x o • Assume that public support for the social issue underlying the campaign is uncertain; let h̃ denote the uncertain, uniformly-distributed harm with support [0, h̄ ]. Let h denotes the realized harm. • The firm can either concede to the campaign and implement xA or retain x and bear the harm; π (x ) − h • If the firm concedes, it bears residual harm βh; π (xA ) − βh • Firm concedes iff π (x ) − π (xA ) h ≥ ho ≡ 1−β • Higher β means firms concede less frequently Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 12 / 59 A Campaign The Campaign • Note that the policy x affects the campaign outcome only through the willingness of the firm to resist. • It does not diminish the public support for the campaign because of the trust gap • The probability q (x ) the campaign succeeds is q (x ) = Pr (h ≥ ho ) = 1 − π (x ) − π (xA ) (1 − β)h̄ • Comparative statics of q (x ) • Decreasing in x because the firm has less incentive to resist • Decreasing in β (less reason to concede) • Increasing in h̄ (scale or intensity of the campaign) • Activist has preferences UA = z (x ) − αh̄, where z (x ) is the perceived social benefits and α is the marginal cost • Expected utility is EUA (x ) = q (x )z (xA ) + (1 − q (x ))z (x ) − αh̄. Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 13 / 59 A Campaign The Campaign • Activist can choose the scale or intensity h̄ of the campaign • The optimal campaign intensity h̄ ∗ (x ) maximizes EUA (x ) and is h̄∗ (x ) = (π (x ) − π (xA ))(z (xA ) − z (x )) α (1 − β ) 12 • h̄ ∗ (x ) is strictly decreasing in x; self-regulation results in less intense campaigns, since the activist gets some of what it wants for free • A higher demand increases h̄ ∗ (x ); activist has more to gain • Decreasing in α; increasing in β • The expected utility of the activist with the optimal campaign is EUA∗ (x ) = z (x ) − (1 − 2q ∗ (x ))(z (xA ) − z (x )) = z (xA ) − 2αh̄∗ (x ). • The activist campaigns iff q ∗ (x ) ≥ 21 . • Assume that the activist’s demand is principled; i.e., exogenous Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 14 / 59 A Campaign Timing • Activist demands that the firm adopt a policy xA (xA >> z) • Firm (or industry acting collectively; e.g., U.S. timber industry) either accepts xA or self-regulates to policy x ∈ [x o , xA ) • Self-regulation is irreversible • Activist campaigns or accepts x • Activist cannot commit to campaign • Game ends if activist accepts x • Activist chooses campaign intensity h̄ and launches a campaign • There may be an opportunity for cooperation • Campaign harm h is realized – the public support for the campaign • Firm concedes and implements xA or retains x and bears harm h • Firm cannot commit not to concede to a campaign • Game ends Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 15 / 59 Confrontation and Cooperation Cooperation • Consider an NGO with expertise that a firm does not have • EDF and McDonald’s have conducted 48 joint projects to improve the company’s environmental footprint • Cooperation may be accompanied by certification by the NGO to address the trust gap • The cooperative activist helps the firm discover the benefits from • • • • • self-regulation ex ante, the firm itself can only discover them ex post; i.e., once it concedes to the campaign and changes its policy Consider the case in which cooperation yields a shield against confrontational activists; shields may be imperfect Assume that cooperative activists with expertise and a shield are scarce, so firms (implicitly or explicitly) compete for an engagement Two firms: a profit maximizer P and a CSR firm R The firm not selected by the cooperative activist is targeted by the confrontational activist. Note: There is no strict gain for an activist to have both cooperate and confront relative to two specialized activists Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 16 / 59 Confrontation and Cooperation Cooperation and Matching Private Politics and Matching contribution Cooperative activist positive externality offers selection CSR firm Confrontational activist social pressure (harm) concessions Profit-max firm Which firm is matched with which activist? CSR: Corporate social responsibility Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 17 / 59 Confrontation and Cooperation The Reservation Values • Let c denote the cost of changing policy; e.g., the difference in profit • Let b̃ denote the uncertain benefits from changing policy and b̄ < c the mean • The firm concedes to the campaign if h > c −1b̄−−βI θs , where s is the social benefits from changing its practices, θ is a CSR parameter, and ( 1 if firm is R I = 0 if firm is P • Note: CSR could be strategic; e.g., chosen by a firm to be more attractive to consumers or to the cooperative activist • CSR here means changing policy (conceding to the campaign) when the cost exceeds the realized benefits; CSR is costly Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 18 / 59 Confrontation and Cooperation Confrontation and CSR • The reservation value is the expected harm, EH i , i = P, R, from a campaign by the confrontational activist. EH i differs for the firms "Z c −b̄−θs # Z h̄ 1− β 1 EH R = hdh + c −b̄−θs (c − b̄ − θs + βh )dh h̄ 0 1− β = c − b̄ − θs − (c − b̄ − θs )2 βh̄ + , 2 2(1 − β)h̄ • The confrontational activist chooses the campaign intensity h̄i , i = P, R, and h̄P > h̄R • The reservation values EH i (h̄i ) satisfy EH P (h̄P ) > EH R (h̄R ) • That is, CSR is a component of the firm’s objective function and offsets some of the cost Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 19 / 59 Confrontation and Cooperation Competing for Cooperation • Cooperation means that firm i changes its policy if b ≥ c − I θs − yi , where yi denotes the agreement with the cooperative activist. • Probability the activist achieves a change in policy increases in yi • In exchange for agreeing to yi , the firm receives two benefits • The ex ante discovery of the realization b • A shield from the confrontational activist • A firm and the cooperative activist could bargain over yi , but if cooperative activists are scarce, firms compete for an engagement • That competition would take the form of an ascending auction • Let a firm bid yi , i = P, R • The cooperative activist seeks to maximize the probability that the firm it engages changes its policy • Pr P (change ) = Pr (b ≥ c − yP ); Pr R (change ) = Pr (b ≥ c − θs − yR ) • The cooperative activist chooses P iff yP > θs + yR Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 20 / 59 Confrontation and Cooperation Matching of Firms with Activists • Two firms P and R and a confrontational and a cooperative activist • The firms compete for the engagement with the cooperative activist • The firm not chosen incurs a campaign by the confrontational activist • How are firms matched with activists? • The CSR firm has an advantage in the auction, but its reservation value is lower, so losing the auction is less costly • Assume that both firms would reject the demand of the • • • • confrontational activist if targeted Result: If both firms would reject the demand of the confrontational activist, the cooperative activist chooses the CSR firm CSR firm’s bidding advantage outweighs its lower reservation value CSR firms thus are matched with cooperative activists and profit-maximizers incur campaigns. A firm could do CSR to be selected by the cooperative activist Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 21 / 59 An Experiment Online Experiment on the Cooperation-Confrontation Model • The experiment focuses on three factors not captured by the model: 1) favoritism, 2) awareness of the positive externality, and 3) objectives (what does an activist maximize) • The externality: The more aggressive is the campaign the greater is the expected harm from the confrontational activist and the more the firms bid to work with the cooperative activist • The activists would be expected to exploit this externality • Kert Davies (2010, p. 196) of Greenpeace wrote, According to reports from Greenpeace staff of conversations with people at companies it has targeted, corporations may have a greater fear of its campaigns than those of other organizations because of the strong connotation of the Greenpeace brand. Thus some of the negative perceptions of the organization may actually serve to support its cause, upholding Machiavelli’s proposition that it is better to be feared than loved, when campaigning against corporations. Indeed, the notion that NGOs often can be more effective by imposing harms rather than offering benefits is consistent with the economics literature, ... Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 22 / 59 An Experiment Experiment • There could be favoritism on the part of activists • The cooperative activist could favor the CSR firm • If so, the CSR firm should bid less because of its advantage • The confrontational activist could conduct a more aggressive campaign against the profit-maximizer • Are these beliefs likely? • Are the objectives of the activists their own accomplishments or the aggregate accomplishments of activism; i.e., of both activists? • Cooperative activist should fund a more intense campaign if aware of the externality or if its objective is aggregate accomplishments • An online experiment with four panels; eliciting their choices • The game is "played" by drawing a participant at random from each panel and executing their choices Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 23 / 59 An Experiment Experiment Findings • The cooperative activist exhibits favoritism for the CSR firm, even though its CSR is sunk and the firms are strategically equivalent • The firms anticipate this favoritism, and the CSR firm bids less than the profit-maximizer when the harms are equal • The cooperative activist is still more likely to choose the CSR firm • The confrontational activist chooses a more intense campaign against the the profit-maximizer • The cooperative activist is still more likely to choose the CSR firm • CSR firms thus are more likely to match with cooperative activists • Profit-maximizers are more likely to incur campaigns • Cooperative activists that recognize the externality contribute funds to the campaign of the confrontational activist • Confrontational activists that recognize the externality request more funding from the cooperative activist • Activists with aggregate objectives contribute and request more • Experiment provides evidence of favoritism and cooperation among activists Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 24 / 59 Self-Regulation The Activist’s Campaign Decision • Returning to the confrontation model • The expected utility of the activist is EUA∗ (x ) = z (x ) − (1 − 2q ∗ (x ))(z (xA ) − z (x )) • Activist accepts x and does not campaign if EUA∗ (x ) ≤ z (x ) or q ∗ (x ) ≤ 12 , which is equivalent to a weighted welfare condition z (xA ) + 4α 4α π (xA ) ≤ z (x ) + π (x ). 1−β 1−β • The activist takes the preferences of the firm into account, because those preferences determine the firm’s response to campaign harm • A higher weight on profit the more costly is a campaign and the greater the residual harm • Assume that the activist’s demand is principled and not strategic Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 25 / 59 Self-Regulation Self-Regulation: Forestalling a Campaign • The self-regulation policy x ∗ that forestalls a campaign satisfies the weighted-welfare condition as an equality • x ∗ is strictly decreasing in xA , so a higher demand leads to less self-regulation • Intuition: An increase in the demand (1) makes it less likely that the firm will concede to the campaign and (2) causes the activist to mount a more costly campaign. • Both make the activist worse off, so it is then easier for the firm to forestall a campaign through self-regulation. • x ∗ is strictly decreasing in α and β • q ∗ (x ∗ ) = 12 , so the activist is indifferent between campaigning and not; EUA (x ∗ ) = z (x ∗ ) • q ∗ (x ) is decreasing at x = x ∗ Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 26 / 59 Self-Regulation Forestalling a Campaign Figure 1 Forestalling a Campaign activist weighted utility campaign Baron (Stanford University) no campaign NGO Conference June 5, 2014 27 / 59 Self-Regulation The Targeted Firm • The firm can accept the demand, forestall the campaign, or bear a campaign • If it chooses to bear a campaign, it still may self-regulate to reduce the intensity of the campaign • The firm’s expected profit is E π ∗ (x ) = π (xA ) + h̄∗ (x ) α(π (x ) − π (xA )) −β 2 z (xA ) − z (x ) • The firm rejects the demand if the term in brackets is nonnegative or z (xA ) + α α π (xA ) ≤ z (x ) + π (x ). β β • Let x r (xA ) satisfy this as an equality. Figure 2 • x r (xA ) is decreasing in the demand xA • x r (xA ) is decreasing in α and increasing in β • If the firm chooses to bear a campaign, it self-regulates at x̂ (xA ) ∈ arg max E π ∗ (x ). x Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 28 / 59 Self-Regulation Firm’s Response to the Activist’s Demand Figure 2 Accepting or Rejecting the Demand firm weighted utility accept demand Baron (Stanford University) reject demand NGO Conference June 5, 2014 29 / 59 Self-Regulation Equilibrium with a Principled Demand • x ∗ (xA ) and x r (xA ) are decreasing and increasing, respectively, in β • • • • • • and are equal at β = 51 If residual harm is high, forestalling a campaign is cheap (x ∗ (xA ) is low), so the firm wants to avoid a campaign. The firm then self-regulates at x ∗ (xA ) If residual harm is low, then forestalling self-regulation is costly (x ∗ (xA ) is high). The firm self-regulates at x ∗ (xA ) unless it is too costly. If it is too costly, it chooses x̂ (xA ) and bears a campaign The firm can self-regulate to decrease the campaign intensity; i.e., x̂ (xA ) > x o Private politics is successful to the extent of the self-regulation x ∗ (xA ) − x o or x̂ (xA ) − x o Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 30 / 59 Self-Regulation Equilibrium with a Principled Demand Figure 3 Equilibrium Strategies A B Firm rejects demand, activist not campaign D Firm rejects demand, activist campaigns C Activist campaigns, firm accepts demand if activist campaigns Baron (Stanford University) Activist not campaign, firm accepts demand if activist campaigns NGO Conference June 5, 2014 31 / 59 Self-Regulation A Strategic Demand • A fully strategic activist recognizes that by moderating its demand • • • • • • • • the firm will increase its self-regulation, as illustrated in Figure 1 The activist moderates its demand to maximize x ∗ (xA ) and avoid the cost of a campaign At some point, however, the firm rejects and the activist campaigns For β < 15 the firm thus may choose x̂ (xA ) and bear a campaign The equilibrium demand x̂A is such that the firm self-regulates to x ∗ (x̂A ) and forestalls the campaign The firm is indifferent between forestalling and incurring a campaign On the equilibrium path campaigns are forestalled. The equilibrium thus is a demand x̂A and self-regulation x ∗ (x̂A ) Private politics is successful to the extent of the self-regulation x ∗ (x̂A ) − x o even though there is no campaign. Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 32 / 59 Self-Regulation Equilibrium with a Strategic Demand Figure 4 Equilibrium Demand and Self-Regulation Policy Activist weighted utility Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 33 / 59 Self-Regulation Target Selection by the Activist • The strategic activist initiates private politics only if EUA∗ (x ∗ (x̂A )) ≥ z (x o ) • The activist prefers to target: • "bad actors" (x o low) • "soft firms" (low β and low α) • Argenti (2004) concluded, Truly socially responsible companies are actually more likely to be attacked by activist NGOs than those that are not ...Our interviews with Global Exchange suggested that Starbucks was a better target for the fair trade issue because of its emphasis on social responsibility, as opposed to a larger company without a socially responsible bent. • There is some empirical support for the selection of soft targets. Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 34 / 59 Self-Regulation Self-Regulation, Cooperation, and CSR • Definition of CSR: (1) Goes beyond the requirements of law and regulation and (2) is something a profit-maximizer would not do • The label of CSR can be given to self-regulation, but it is something done by a profit-maximizer in response to social pressure • An increase in social pressure (due to market campaigns) thus results in an increase in (labeled) CSR • A profit-maximizer can also behave like a CSR firm to be more attractive to a cooperative activist (with a shield) • Similarly, cooperation can be a label given to a firm’s decision to self-regulate accompanied by an invitation to an NGO to join it in implementing the self-regulation it has already decided to do. • CSR and cooperation as labels are observationally equivalent to their "true" counterparts, and distinguishing them requires determining whether the firm is under social pressure. Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 35 / 59 The Market for Activism The Market for Activism • A market in which donors fund activists and activists target firms • Distinguish between the threat of activism and actual targeting • Many more firms are threatened than can be targeted • Identify the scope of activism–the set of firms that self-regulate or bear a campaigns as a result of the threat of activism • Activists have aligned preferences and could be thought of as maximizing the scope of activism • Similarly, donors have aligned preferences and those preferences are aligned with those of activists. They could be thought of allocating their donations to maximize the threat and scope of activism • Self-regulation takes place in the presence of the threat of activism but before individual firms are targeted • Once a firm is targeted by an activist, it is too late to self-regulate. Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 36 / 59 The Market for Activism Modeling • Firms associated with a social issue–the environment, inequality • The set can be broader than an industry • Confrontational activists that have the issue on their agendas • Assume two types: moderates and radicals • Donors concerned with the social issue • Firms are more numerous than activists • Some firms thus are not targeted, but all are threatened by activism • The threatened firm does not know whether it will be targeted, so it must prepare for that possibility; i.e., it must self-regulate before it knows whether it will be targeted • The threat may be the principal force in strategic activism and private politics; i.e., self-regulation induced by the threat Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 37 / 59 The Market for Activism Modeling • Once funded, a moderate activist is randomly matched with a firm, • • • • • and once matched it decides whether to accept the firm’s self-regulation or launch a campaign against it The probability that a firm is targeted is the ratio of the number of activists to the number of firms, where the former is endogenous. There is a degree of safety in numbers for firms that are threatened Funding of activists by citizens determines the number of activists The impact of activism is indicated by the number of firms threatened rather than the number targeted Claim: The threat broadened with the innovation of market campaigns, which exposed many more firms to the threat of activism and led to the surge in self-regulation, CSR, and cooperation Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 38 / 59 The Market for Activism A Simplified Model • Distinguish among firms using their vulnerability v ∈ [0, v̄ ] • Firms differ in their vulnerability to a campaign • Could depend on reputation • Could depend on factors such as brand equity, consumer or industrial products, public facing, etc. • Firms are otherwise identical • To simplify the analysis, assume that a campaign yields either very low harm or very high harm; the campaign either succeeds or fails • Represent this by the probability p (v ) of campaign success; p (v ) is assumed to be strictly increasing in v . • Hard firms have low v ; soft firms have high v • The only purpose of self-regulation is to forestall a campaign. Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 39 / 59 The Market for Activism Hard and Soft Firms • The vulnerability of firms and the probability of campaign success depend on the social issue • Epstein and Schneitz (2002) found in an event study that firms targeted for environmental issues during the 1999 Seattle WTO demonstrations had significantly lower abnormal returns, whereas firms targeted for labor practices had normal returns • King and Soule (2007) found significantly lower abnormal returns for firms that incurred protests by NGOs funded by labor unions Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 40 / 59 The Market for Activism Activists • Activist’s perceived social benefits are z (x ) if it accepts self-regulation x by a firm • A successful campaign results in a policy x̄ • Activist can be moderate or radical; all moderate activists are the same and all radical activists are the same • Activist’s utility Ui from an encounter with a firm ( Ui = z (x ) p (v )z (x̄ ) + (1 − p (v ))z (x ) − k (v ) + Jy if i accepts x if i camapigns, where J = 1 indicates radical (a taste for confrontation), y is the utility from confrontation, and the cost of a campaign is k (v ); k 0 (v ) < 0 • Activists are randomly matched with a firm (discussed below) • Some firms are too hard to target (they profit maximize) • Some self-regulate • Some incur a campaign Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 41 / 59 The Market for Activism Subgame Equilibrium • The activist accepts self-regulation x if p (v )(z (x̄ ) − z (x )) − k (v ) ≤ 0, so as to avoid the cost of a campaign and the risk of failure • Some firms are too hard; i.e., can maximize profits and not be targeted. o denote the most vulnerable profit-maximizer • Let vM o o p (vM )(z (x̄ ) − z (x o )) − c (vM )=0 • For higher v the firm can forestall a campaign with xM (v ) • The forestalling self-regulation xM (v ) is strictly increasing in v because p (v ) is increasing and k (v ) is decreasing in v ∗ the firm prefers to incur • Self-regulation is costly, so for some vM rather than forestall a campaign o , v̄ ] = [v o , v ∗ ) ∪ [v ∗ , v̄ ] • The scope of moderate activism is [vM M M M Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 42 / 59 The Market for Activism Self-Regulation • The expected profit of the firm once it is targeted is E π (x, v ) = p (v )π (x̄ ) + (1 − p (v ))π (x ). • Let ξ M be the probability a firm is targeted by a moderate • The firm must self-regulate before it knows whether it will be targeted, and its ex ante expected profit is E ΠM (x, v , ξ M ) = ξ M E π (x, v ) + (1 − ξ M )π (x ) = π (x ) − ξ M p (v ) (π (x ) − π (x̄ )) . • If the firm does not self-regulate, it maximizes its profit π (x ), since p (v ) does not depend on x Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 43 / 59 The Market for Activism Self-Regulation • The firm forestalls the activist rather than risk a campaign if ∆ΠM (v , ξ M ) = π (x ) − π (xo ) + ξ M p (v )(π (xo ) − π (x̄ )) ≥ 0. • Let x̂M (v ) denote the minimum forestalling policy • x̂M (v ) is decreasing in ξ M ∗ ( ξ ) denote the most vulnerable firm that self-regulates • Let vM M • The characterization for a radical activist is analogous • x̂R (v , y ) is decreasing in y • vRo (y ) is decreasing in y • More radical activists threaten more and harder firms Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 44 / 59 The Market for Activism Equilibrium in the Confrontation Market Figure 2 Equilibrium Configuration o ¤ [vR¤ (»R ; y) < vM ; vM (»M ) < v¹] F self‐ regulates F maxes F self‐ F bears a profits regulates campaign No threat R threatens a campaign vRo (y) R accepts Baron (Stanford University) vR¤ (»R ; y) R accepts x^R (v; y) R cam‐ paigns F bears a campaign M threatens a campaign o vM ¤ vM (»M ) M accepts M campaigns x^M (v) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 45 / 59 The Market for Activism Subgame Equilibrium • Some firms can be too hard for any activist to pose a threat • A highly vulnerable firm can it find it too costly to self-regulate because the activist requires too much not to campaign • Softer firms may incur a campaign by the activist and harder firms self-regulate and forestall the activist • The intuition is that it is cheap for a low vulnerability firm to self-regulate to forestall the activist because the probability of campaign success is low • It is expensive for a high vulnerability firm to self-regulate, and some choose to incur a campaign o) • Radical activists pose a threat for firms that are too hard (v < vM for moderate activists Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 46 / 59 The Market for Activism Donors • Citizens have a warm (or cold) glow and, if warm, also care about activists’ accomplishments, which are uncertain ex ante • Citizens are of type w ∈ [w , w̄ ], w̄ > 0, where higher w means a greater warm glow from donating • Donors also care about what their donation accomplishes Aa z̄, where a is the donation, A funds an activist, and z̄ is the expected social benefits • Each citizen can donate a or nothing ( 0 if w does not donate, UD (w ) = a if w donates a A z̄ + w − a • Donors do not know which firm the activist they fund will target • The expected net benefits generated by a moderate activist are: (assuming monotonicity in v ) z̄M = Z v ∗ (ξ ) M M o vM +ξ M Baron (Stanford University) (z (x̂M (v )) − z (xo )dF (v ) Z v̄ ∗ (ξ ) vM M p (v )(z (x̄ ) − z (xo )dF (v ), NGO Conference June 5, 2014 47 / 59 The Market for Activism Donations • The distribution of donor types is G (w ) • Donors can direct a donation to a moderate or radical • A donor donates if Aa [z̄M + w ] − a ≥ 0. ∗ ≡ A − z̄ fund moderate activists. • Citizens with w ≥ wM M • The donations DM (y ) to moderate activists are DM (y ) = aNc Z w ∗ (y ) R ∗ wM dG (w ), • Nc is number of citizens; NF is number of firms • NM (y ) = DMA(y ) moderate activists are funded. • The probability a firm is targeted is ξ M (y ) = NNM ((yy)) , where the FM R v̄ number of firms threatened is NFM = v o NF dF (v ). M • Rational expectations requires that ξ M = ξ M (y ). • Similar analysis for a radical activist Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 48 / 59 The Market for Activism Aligned Preferences and the Scope of Activism • Activists have aligned preferences • If the objective of an activist is to maximize the aggregate accomplishments of activism rather than its own accomplishments and if it is the threat of activism that matters, activists should spread themselves across firms to maximize the scope of activism • Donors have aligned preferences and those preferences are aligned with those of activists • Donors would be expected to make contributions to moderate and radical activist to pose threats to as many firms as possible • Even if there is no explicit coordination, market forces could spread donations and threats to maximize the impact of activism Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 49 / 59 The Market for Activism Model Assumptions–Matching and Spreading • Activists are assumed to coordinate and spread themselves over potential targets • So the probability that any one firm is targeted is the same; e.g., ξ M • Donations are made ex ante (before an activist has a target) • Donors spread out their donations to increase the "scope of activism"; Citizens with stronger preferences fund radical activists • Do donors spread their donations? Are they guided by a strategic or invisible hand? • Is there evidence of coordination and spreading? • They should spread and coordinate since they have aligned preferences • Experiment reveals coordination • Activists exchange information and provide assistance–typically in-kind • Big donors allocate funds strategically • Small donations are coordinated; e.g., through Tides Foundation Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 50 / 59 The Market for Activism Funding: Jarol Manheim for the Chamber of Commerce organizations listed under each foundation in our earlier analysis. For this subset of funding activity during this four-year period, total awards exceeded $57,000,000. Again, please see footnote 62 for a summary and discussion of the sources and limitations of the underlying data. TABLE 1. TOTAL AWARDS TO SELECTED RECIPIENTS BY SELECTED FOUNDATIONS, 2009–2012 FOUNDATION OR GRANTOR TOTAL AWARDS 2009–2012 Ben & Jerry’s Foundation $230,000 Marguerite Casey Foundation $3,450,000 Discount Foundation $340,0001 Ford Foundation $26,127,000 General Service Foundation $789,000 Hill-Snowdon Foundation $370,0002 WK Kellogg Foundation $4,110,000 Kresge Foundation $2,970,0003 Mertz-Gilmore Foundation $320,000 Moriah Fund $370,000 Nathan Cummings Foundation $865,000 Needmor Fund $350,0002 New York Foundation $658,000 Norman Foundation $420,0003 North Star Fund $260,000 Jesse Smith Noyes Foundation $320,000 Open Society Institute $1,276,0002 Public Welfare Foundation $5,535,0002 4 Rockefeller Foundation $2,965,000 Surdna Foundation $3,263,000 Unitarian Universalist Veatch Grants $2,026,000 The reported figure is for grants to the organizations listed in this report. The Foundation reported that overall, between 2009 and 2012, it awarded grants totaling $1,195,000 for activities related to “independent worker organizing.” 2 Data cover 2009–2011. No data available for 2012. 3 Data cover 2010–2012. No data available for 2009. 4 Excludes grants to In These Times and The American Prospect totaling $235,000 to encourage news coverage and commentary. 1 Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 51 / 59 has initiated, shaped, supported, and sustained organizing and other activity at multiple The Market for Activism points along the supply chain, though most notably at fast food restaurants. We can see some of these relationships mapped out in Figure 6. FCWA, in turn, supports a number of efforts by its members, including, at this writing, CIW’s Fair Food campaign, ROC’s Dignity at Darden campaign, and the UFCW’s Making Change at Walmart campaign which, as we have seen, is tied to union-backed OURWalmart. The Food Chain Workers Alliance, then, is a nexus through which pass many of the forces we have described here. Funding: Jarol Manheim for the Chamber of Commerce FIGURE 6. PARTIAL RELATIONAL MAP OF THE FOOD CHAIN WORKERS ALLIANCE Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference www.workforcefreedom.com June 5, 2014 52 / 59 The Market for Activism Funding: Jarol Manheim for the Chamber of Commerce FIGURE 4. SOURCES AND AMOUNTS OF SELECTED FUNDING OF RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITIES CENTER AND AFFILIATES, 2009–2012 At one step further removed from established unions, but nonetheless tied to them, is Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 53 / 59 Commentary Observations on Empirical Research on Private Politics • The data needed is seldom mandated by government; several studies do media searches • Some studies have calculated the probability of campaign success • Lenox and Eesley find that 44% of boycotts and campaigns succeeded • A substantial portion of the cases are shareholder initiatives • Self-regulation, however, is hard to observe • Some researchers use participation in self-regulation organizations or programs as indicators • Industry programs; SFI, Responsible Care • Issuance of a CSR report, participation in UN Global Compact, and have a board CSR committee • These are very indirect measures and could be public relations • Target selection by NGOs • Some evidence that soft firms are targeted • There is an ex ante-ex post problem in self-regulation • After self-regulation a firm is softer than it is before self-regulating Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 54 / 59 Commentary Observations on Empirical Research on Private Politics • Endogeneity: many studies use targeted firms and campaigns as their unit of observation • We want to know which firms are not threatened, which are, and which are targeted; i.e., how targets are selected • Event studies (e.g., boycotts) are difficult because identifying the event window is hard • Epstein and Schneitz is likely OK because the size of the protests was a surprise • Activist demands can be principled (e.g., nuns) or strategic (PETA to attract media attention). Can we distinguish? • Some researchers study a single firm or industry rather than a cross-section: Harrison and Socrse (suppliers of Nike, Addidas, Reebok), King and Lenox (chemical firms), Locke, Qin, and Brause (Nike), and Ingram, Yue, and Rao (Wal-Mart) Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 55 / 59 Commentary The Challenge of Normative Analysis • Here an NGO is viewed as an organization led by activists with their own preferences • What preferences drive activists’ strategies? • People self-select into activism • They may sacrifice when doing so • Those who self-select may have extreme preferences that are not representative of the public or of social welfare • They may want redistribution as much as controlling a negative externality • Asking them about their preferences does not work, just as asking corporations about their objectives does not work (Michigan conference) Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 56 / 59 Commentary Preferences and Well-Being Well-Being: Societal, Activist, Industry Well-Being; Profits Activist societal well-being** Aggregate societal well-being* Target profits Profitmaximization Societal optimum Activist optimum Policy * Everyone weighted equally ** With redistribution Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 57 / 59 Commentary Conclusions • The principal effect of strategic activism may be due to its threat rather than its actuality • Those threatened by corporate and market campaigns self-regulate • To forestall a campaign if targeted • To lessen campaign intensity if targeted • The surge in CSR may be due to the broadened threat of activism • CSR may be a label given to self-regulation • CSR could be a strategy to obtain the shield of cooperation • The observed cooperation between NGOs and firms may be • Based on expertise • In name only–a firm that decides to self-regulated invites an NGO to work with it on the details of implementation • Observed campaigns are against soft firms; harder firms self-regulate • Some firms are too hard for private politics • Radical activists may tackle harder targets than do moderate activists • The funding of NGOs results from (1) their accomplishments and (2) warm glow preferences. It is likely strategically directed. Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 58 / 59 Commentary The Private Politics Hold-Up Problem • Set-up – (Some) activist(s) and (some) firm(s) reach an agreement [SFI] – Firm makes a public pledge (perhaps conditional on circumstances [Ford]) – Firm participates in NGO system [Domtar and FSC] • Agreement does not preclude public or private politics by nonsignatories – Everyone has standing to intervene • Nothing prevents more extreme activists from attacking the firm(s) or the agreement – Private politics social criticism or campaigns – Media campaigns – Pressuring customer-by-customer [FSC backers] • Critics can turn to public politics • Lawsuits can be filed – Legitimate or extortion • Consequently, an agreement may not provide a strong shield even when the private governance arrangement works [SFI, FLA] Baron (Stanford University) NGO Conference June 5, 2014 59 / 59