The Impacts of Expanding Access to High-Quality Preschool Education ElizabEth U. CasCio

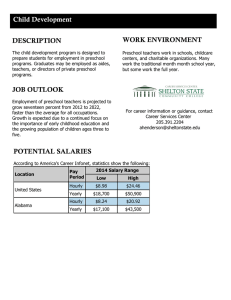

advertisement