Research Paper Managing individual conflict in the contemporary British workplace Ref: 02/16

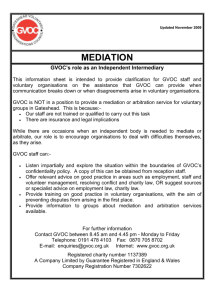

advertisement