History of the Human Sciences

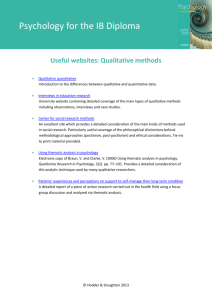

advertisement