The Oklahoma Review 1 Volume 14 Issue 1

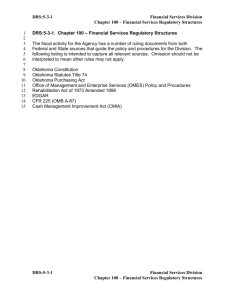

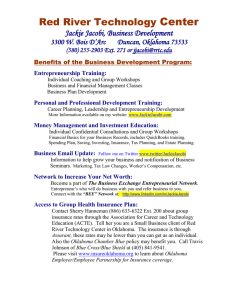

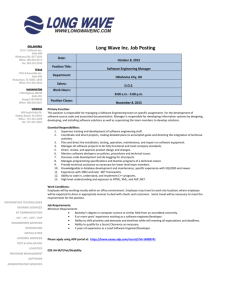

advertisement