Sense of Place An Elusive Concept That Is Finding a Home in

advertisement

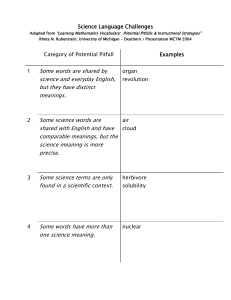

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Senseof Place An ElusiveConcept That Is Finding a Home in EcosystemManagement "Sense ofplace" offers resource managers a way toidentify andrespond totheemotional and spiritual bonds people form withcertain spaces. Weexamine reasons fortheincreasing interest intheconcept andoffer fourbroad recommendations forapplying sense ofplace toecosystem management. Byinitiating a discussion about sense ofplace, managers can build aworking relationship with the relationship with citizens thatreflects public thatreflects thecomplex web of webof lifestyles, meanunmetchallenges associated the complex lifestyles, meanings, andsocial relations relations endemic to a with ecosystem management ings,andsocial endemic toaplace. Sense of placecanbe is treatingpeopleasa rightfulpartof placeor resource. language thateases discusecosystems. In manyecosystem mod- theshared and problems els,despiteoccasional rhetoricto the sionsof salientissues By Daniel R.Williamsand undercontrary,thereis still a tendency to andthataffirmstheprinciples Susan I. Stewart treatpeopleasautonomous individual lyingecosystem management. agents outside theecosystem, at besta Thoughthetermsense ofplace resourceof valuesto be incorporated mains elusive,ill defined, and contromanagement conintodecisions, at worstagents of cata- versialasa resource strophicdisturbance of an otherwise cept, it is turning up in a surprising smoothlyrunning system.Many number of academic discussions of scholarshavemadesuggestions for ecosystem management(Grumbine bringing social concepts andvariables 1992; Samsonand Knopf 1996) as intoecosystem models andassessments wellasin recentecosystem assessments (Driveret al. 1996;ForceandMachlis (USDA 1996). Similarly,in popular 1997). Far fewer have demonstrated mediaanda widerange of publicpolhow day-to-dayland management icyissues, Spretnak (1997)sees a growof placeandremightchange whenpeoplearerecog- ing interestin sense nizedaspartof theecosystem. latedconcepts, like community, place Sense ofplace isa concept withgreat attachments, symbolic meanings, and potential forbridging thegapbetween spiritual values. Forherthissuggests a the science of ecosystems and their resurgence of therealityof placethat management (Mitchell et al. 1993; haslongbeendenied, suppressed, and Brandenburgand Carroll 1995; devalued bya mechanistic viewof naSchroeder 1996).Butironically, sense ture. At this point, with so many of placeissometimes seenasa barrier groups readytojointhesense-of-place to sensibleresourcemanagement.parade,we think it is usefulto ask What is meantby Managers who haveheardthe term three questions: of placein itsvarious formsand usedby peopleopposed to proposed sense changes wronglyconclude that sense guises? Why is it increasingly in the of placeis an argumentfor keeping hearts of citizens and on the minds of themfromdoingtheirjob.In fact,the landmanagers? Andfinally, whatdoes conceptoffersmanagers a wayto an- it suggest aboutmanaging ecosystems? ticipate,identify,andrespond to the bonds people formwithplaces. Byini- DefiningSenseof Place tiating a discussion about senseof Therearemanydefinitions anddeplace,managers canbuilda working scriptions of sense of place.Asa geo- ne of the great and largely 18 May 1998 graphicterm,placecommonlyrefers or dimensions thatcapturethemulti- At Devil'sTower National Monument, to a centerof meaningandfeltvalue: faceted natureandcomplexity of what the NationalParkServiceis caughtbeof place: tween a rock and a holy place:the site "Whatbegins asundifferentiated space wewill referto hereassense becomes placewhenweendowit with ß theemotional bondsthatpeople is sacred to Native Americans and a value"(Tuan1977,p. 6). A seemingly formwithplaces (atvarious geographic destination of choice for rock climbers. overtimeandwith familiarity Thefeelingsassociatedwith places straightforward approach to defining scales) havealwaysbeena part of our relasenseof placeis to think of it asthe with thoseplaces; tionship with the natural world but at collection of meanings, beliefs,symß thestrongly feltvalues, meanings, an intuitive level-as somethingmany and symbols that are hard to identify bols,values, andfeelings thatindividualsor groups associate witha particu- or know(andhardto quantify),espe- peopleunderstoodbut did not talk lar locality.In somerecentecosystem ciallyif one is an "outsider" or unfa- about or name. Awareness of sense of assessments, this collection of meanplacehasincreasedin proportionto miliarwith theplace; ß thevaluedqualities of a placethat globalizationand our capacityto make ingsandfeelings isreduced to a single attributeandviewedasjustanother evenan "insider"may not be con- and remake placesvirtually overnight. oneof manypotential attitudes, values, sciously awareof untiltheyarethreatandbeliefs people mightholdtowarda ened or lost; of places andemphasizes people's tenresource (USDA 1996).The problem ß thesetof placemeanings thatare dencyto formstrong emotional bonds with theserudimentary definitions is activelyandcontinuously constructed withplaces. It isworthnotingthatalthey tend to diminishthe holistic, and reconstructed within individual thoughwe emphasize theimportance emotive, social, andcontextual quality minds, shared cultures, and social of recognizing "local"meanings, these should not be limited to residents' of theidea,robbing it of theveryrich- practices; and ß the awareness of the cultural, his- sense nessthatisitsappeal. ofplace.Manytourists andreguPlace, placeattachment, andsense of torical, and spatialcontextwithin lar visitors havestrongattachments to placeareusedbyvarious writersto de- whichmeanings, It isnotthepossessors of meanvalues, andsocial in- places. scribe similar but not identical conteractions are formed. ingsthatarelocal,but the m6anings cepts.Dra•ing fromthisdiversity of Mostpeoplewhointer}ect sense-of- themselves. Similarly,"insiders"are intonaturalresource is- thosewhoknowwhata placemeans thought(Tuan 1977; Hester1985; placeconcerns to Agnewand Duncan 1989; Shamai sues probably havein mindsomething a group.Toooftenplanners are"out1991; Altman and Low 1992; Groat akinto oneof thefirstthreeinterpreta- side"the socialcirclesthat assign 1995;Harvey1996;Relph1997),we tions.Senseof place,for mostpeople, meaning to a placeandtherefore tend suggest several overlapping approaches refers to therichandvariedmeanings to discount them. Journal of Forestry 19 of socialprocesses. Bothecosystemscanbeinvoked bydiverse andconflictandplaces aredynamic, witha past,a inggroups---local commodity haterests of place is the reason present, anda future. seeking to maintain a wayof life,enviSense of placeisshaped byincreas- ronmentalists embracingLeopold's behind commonly inglycomplexsocial,economic, and landethic,NativeAmericans focusing political processes. At a local level, on the spiritual or transcendent qualiaccepted urban place meanings areless stable thanthey tiesinherentin a place,recreation and planning tools, such oncewere,beingbuffeted byincreas- wilderness enthusiasts voicingconinglydistant anduncontrollable social cernsaboutnewor nonconforming as zoning ordinances, andeconomic forces. Meanings have uses, andheritage preservationists trybecome more individualized and ing to maintain landscape character or regional tourism boundaries havebecome moreperme- restore presetdement ecological condiable.In addition, a sense of placethat tions. Such sentiments are sometimes marketing authorities, at one time may havebeenlargely dismissed asthemerelycosmetic orroand regulations on shaped andmaintained bycommunity manticconcerns of designers, nature insiders isnowincreasingly subject to lovers,andheritageenthusiasts. Yet architectural styles. more distantmarket and political evenwhatplanners andscientists put forces. forward asa data-driven description of Thelasttwodimensions, emphasiz- Forexample, tourism,urbanflight, a placein theformof a scientific ashagthesocial processes thatcreate and retirement migration,andeconomic sessment is itselfanothercompeting transform places, describe aspects often development increasingly challenge or sense of thatplace. overlooked in natural resource mancontest traditional meanings of many Within forestplanningdebates agement. Theyexpandsense of place communities. Forlong-timeresidents those various sentiments whether beyondits commonconception asa thisoftenmeans thatanidentitybased localornonlocal in origin, neworlong hard-to-defineattitude,value,or belief onagriculture, forestry, or ranchhag is established---are all legitimate,real, to include the social and historical beingchallenged by newerresidents and stronglyfelt and an important processes by whichplacemeanings are andoutsiders' meanings andusesof source ofpolitical conflict. Competing constructed, negotiated, andpolitically surrounding naturallandscapes. As placemeanings shouldnot be discontested. Understood assomething theydevelop theirownsense of place, missed because theydonotconform to sociallyproduced, sense of placebe- thenewcomers maybecome strongly someexpert's technical sense of place. to thenaturallandscape of an Rathertheymustbeacknowledged, comesanalogous to conceptions of attached if ecosystems as dynamicand open- areawithoutbeingsocially andhistor- not embraced, for resource manageended.That is,justasecosystems are icallyrootedin theplaceor commu- ment to succeed. constituted bybioecological processes,nity(McCoolandMartin1994). Giventhemanydimensions of the The Popularity of Place soplaces arecreated andtakeon particularformsandmeanings asa result concept, competing senses of a place Whyin anageofscientific managementhassucha seemingly nonscientificconcept become a popularrefrain in environmental disputes? Though thetermsense ofplacehasbeenwidely usedin geography and architecture since thecarly1970s,thegrowing emphasison ecosystem management seems tohaveamplified theinterest in theconcept. Onereason foritspresent appealisthatit captures therichvariety of humanrelationships to resources, lands,landscapes, andecosys- Protecting a sense Is Mount t Rushmore a monument Americandemocracyand Manifest Destinyor a symbolof the colonization and oppressionof indigenouspeoples? In suchstronglyfelt values,meanings, and symbols,we are discovering a way to expressour senseof this placeor that communityin languagewe canall share and understand. 20 May 1998 to names thathavemeaning only temsthat multiple-use utilitarianism orderto studythemleavemanypeo- utopian marketing specialist. with a sense to thedeveloper's andotherearlierapproaches to man- ple,layandprofessional, Multiplenames forsingleplaces-agement failedto include.In essence, thatthelargerwhole,theplaceitself, datingfromearliereventsor uses,or theshiftto ecosystem management has has somehow been lost. This reaction to a largeror smaller area-broughta corresponding shiftaway was described in the Forest Service's referring from economic definitions of humanowncritiqueof thefirstroundof forest reflectthemanymeanings theyhave. environmentrelationshipstoward planning (Larson etal. 1990).Though Decidingwhichnameismostappromoreholisticperspectives oftenem- ecosystem management attempts to priatein a givencontextrequires some is apbodiedin thetermsense of place. put silvicultural and forestmanage- thought.Not everyplace-name intoa broader spatial and propriate A sociological explanation for the mentscience in everysituation, asa Forest context,it hasnot fullyad- Servicedistrictrangerstationedin appearance of senseof placecanbe historical Alaska once learned. foundin globalization andtheacceler- dressed the richness of human meanatingpaceof changein society. The ingsandrelationships to thelandthat The rangerwentto thevillageof look and layoutof mostAmerican peopleexpress andwantto seerepre- Kake, a Native Alaskanvillageon Island,to talkwithvillagers communities haveundergone rapid sentedin theplanningprocess. Sense Kuprenof actionwithimplicachange in recentdecades. Concern for of place,in contrast, canencompass abouta proposed sense of placehasrisenin proportion bothnaturalandsocialhistory. tionsfor Saginaw Bay.Althoughthe to thespread of mass cultureandconproposal wasa modest onewithlittle sumption throughentertainment and In Day-to-Day Management potentialimpact,themeetingturned retail goliathslike Toshiba,Time Ourrecommendations forapplying intoa long,hostile event.Neartheend Warner, and Wal-Mart. Think about senseof placein ecosystem manage- of theday,a villagemanapproached howWal-Martalonehasrearranged mentarenot reallynew.Most canbe the rangerandofferedto tell him a theretaillandscapes of Americain the characterized ascommonknowledge story.The rangerdeclined,having past10 years.The social,technologi- amongexperienced managers, espe- spentthe daybearingthe brunt of cal,andeconomic forces of globaliza- ciallythosewhoareknownas"good much criticismand animosityfrom tion have weakened local distinctivepeople-persons." What is new is the meetingparticipants. The man perness,many people say, and with unifyingthemeof sense of place--the sisted,however,and told the ranger cheaper transportation andnewinfor- ideathatplaces havemeaningto peo- that no one had ever referred to their Bayuntilthegunship mation technologies we experience ple. We believethat by puttingthe bayasSaginaw morepartsof theworldthrough inter- human bond with nature in the foreSaginaw anchored therein the late nationaltrade,travel,and the media. Kake,killingmany ground, ratherthantreating it asanin- 1800sandshelled he said,callit Foul Ironically, thoseforces of homoge- teresting but insignificant featureof people.Villagers, nization havemadeplacemoreimpor- thebackground forresource planning, DogBay,a reference to thechum,or tant, not less(Harvey1996;Mander managers canbeginto givethe rela- "fouldog,"salmon run.The ranger's and Goldsmith 1996). What were tionship between peopleandtheland repeated reference to Saginaw Bayhad attentionit re- setvillagers mostly taken-for-granted, subcon- thecareful,systematic on edgeandsouredthe scious meanings of a placecometo the quiresanddeserves. meeting. Knowing andusingcommon surface andseemthreatened by nearly place-names in conjunc1. Knowandusethevarietyoflocal or traditional everyproposed changeto the local place-names. Virtuallyeveryplacehasa tionwith formalnamesandlegaldelandscape. Effortsto introducenew name,whethera roadside especially in communicasignpro- scriptions, landuses whether themeparks,pris- claimsit or not. Namingthings-- tionswiththepublic,signals thatmanons,wildlifepreserves, timberharvests, Adam's task-•isourwayof organizing agers respect thetiespeoplehaveto a landexchanges, or shopping malls-- thoughts abouttheworldaroundus, place. become symbols of external threatsto and anyonewho knowsan areaand 2. Communicate management plans the localsenseof place(Appleyard talks to others about it has a name for in locally recognized, place-specific terms. 1979).Suchplansexpress thesense of it. Arbitrarilychanging a place-name Usinglocalplace-names haspractical placedefinedby an outsider--the sci- canbeasoffensive value.The spatial aschanging theap- aswell assymbolic of thelandscape. The name units usedfor resourceanalysisand entist,government official,corporate pearance developer, or special interest group-- itselfisa powerful linkbetween people planningrarelyfollowsocialboundand thusrepresent the powerof the andplace,symbolizing thehistoryand aries(e.g.,counties, townships). Inoutsider over the local. meaningof the place.When a new stead,biophysical characteristics guide Another reason for the interest in owneror managerchanges a place- definitionof boundaries, resulting in sense of placeis themechanistic view name, the communitymay assume plansthatreferto management areas of nature that dominates our technothatmanyotherchanges willfollowin by number,ratherthan to placesby logicalsociety (Spretnak 1997).Treat- itswake.Housing developers invokea name.The human-createdfeatures,the and incredulity landscape, its socialhistory,scenic ingnatureasa collection of products mix of apprehension or commodities to be sold and isolatfromlocalresidents whenovernight, beauty,communityidentity,family ing properties of the environment in places arerenamed, oftenwith exotic, heritage, andspiritualvalues--allare Journalof Forestry When natural resource scientistsand planners prepare a sciencebased assessment of a forest, their plan is itself a sense of that place--a sense no less valid than the meanings ascribed to the same forest by residents and tourists. an abstract setof resources with many potentialuses.Instead,peopletendto focustheirconcerns onthefateof specificplaces. The dangerof thinking andplanningin abstract termsis the possibility thatthese place-specific featureswill beoverlooked. Forexample, whenclearcutting isproposed andobjectionsareraised,thereis almostalwaysreference to whattheclearcut is next to, where it can be seenfrom, or why that particularstandis not like any otherstandin the forest.All of thesearesocial,place-specific characteristics thatmightnotbeevident from biophysical maps.Forthisreason, it is imperative thatmanagers writeplans and conveymanagement ideasin termsof notonlywhatcouldbedone, but where. been citizen involvement in land and resourcedecisions,but the successof recentgrassroots politicalactionhas given many individuals,especially thosewho speakas local residents concerned about their local commu- nity,newpowerandlegitimacy. 4. Payclose attentiontoplacesthat havespecial butdif•rentmeanings to di•rent groups. Localpolitics isnever morecomplexthanwhenmorethan onegroupclaimsto be representing localinterests. People become attached to particular places foravarietyof reasons, including scenic beauty, spiritual meaning,andpersonalor socialhistory. Peopleand groupscan be attachedto the sameplacebut for differentreasons. Overlapping meanings createspecialchallenges, even for managers who are sensitive to place meanings. The recentcontroversy overDevil's TowerNationalMonumentis a good example of a publicsitewith incompatiblemeanings to different groups. stripped awayto simplifybiophysical 3. Understand thepolitics ofplaces. analysis. At somepoint,managers need The adage"allpoliticsis local"is anto putthesehumanfeatures backinto otherwayof sayingthatwhatis pertheirplans tomakethemrecognizable,sonal,local,andimmediate to people familiar, and real. iswhattheycareabout,acton,andexComputermappingoffersman- pectothersto act on. The extentto agersa new,powerfulway to show whichpolicies andactions arecontro- There is no inherent conflict between plansin a place-specific format.With versialvariesfromplaceto place.If a the Native Americans who treasure computers, mapscanbeconstructed in placeis especially scenic or spiritually promontories for theirsacred signifilayers, orsetsof spatially specific infor- significant or wasthesiteof an event cance in oral tradition and the rock mation.Anycombination of theselay- thathasdeepmeaning to thecommu- climbers wholovechallenging climberscanbedisplayed, including a layer nity,anyproposed change or manage- ing routes--untilboth groupsfind scrutinized. theirvalues that represents placemeanings. Fea- mentactionwill beclosely in thesameplace. turessuchasspecialplaces,spiritual To knowthepoliticsof an issue,one Suchconflictsarenot alwayscenmeanings, traditionalgathering areas, mustknowthepolitics of theplace. teredonuseversus symbolism. Mount and communities of interest have been In the environmentalism of the Rushmore hasrichsymbolic meaning mapped.Eventhe human-builtand 1990s,thereisa growing tendency for for both Native Americans,who seeit human-used featuresfound on any peopleto claimownership of anyissue asa symbolof colonization andoproadmaphelpshowthesocialcontext thataffects them,whetheror notleg- pression, andthosewhorevereit asa withinwhichlandmanagement is oc- islatures, corporations, courts, orgov- shrineto theAmerican experiment in curring.Therearecertainlyresource ernmentagencies wouldtraditionally constitutionaldemocracy.Conflicts management areaswherea map of havegiventhempowerto influence overplacemeanings highlightthefuhuman influencewould be nearly outcomes(Williams and Methany tility of tryingto formulateresource blank;butthat,too,tellsussomething 1995).The often-expressed sentiment plansarmedonlywith theutilizationaboutthe land and the relationship "not in my backyard" simplyreem- maximizing principles of resource subpeoplehavewith it. Mapsarefunda- phasizes thecentrality of placein pol- stitutionandallocative efficiency. mentallysocialandhuman.If people itics.Theenvironmental justice moveThe relativescarcityof natural are included in our consideration of mentisa primeexample of thegrow- places, andthe feelingthat theyget howbestto manage theland,theirim- ingpowerof placemeanings everyyear,addsto theinin Amer- morescarce print on the landneedsto be repre- icanpolitics.Low-income andminor- tensityof debates surrounding their sented onmaps. ity residents, tiredof bearing a dispro- management and use.Someof the An emphasison place-specificportionateshareof pollution and sameurgency seenin thequestto prothinkingis perhapsmostimportant other environmental costs,have suc- tectendangered species is manifested when communicating with others ceeded in changing thegovernment'sin debates overmanaging special, rare about managementplans (Dean rulesforsitinga noxious facility(Har- places. Bothstemfroma fearof irrev1994). Many peoplewho careabout vey 1996). The changes effectively ocable loss.In planningandmanagethe future of the forest do not feel givethe powerto definetheir spaces ment,rareplaces aresometimes inforcomfortable treatingtheecosystem as backto residents. There hasalways mally flaggedfor specialattention, May 1998 justastheEndangered Species Actrequiresidentification andinventoryof threatened andendangered species. A moreformaleffort to identifyand monitor rare places,in particular thosehighlyvaluedbyseveral groups, would be useful. 8:381-98. support sense-of-place considerations. andNaturalResources DDa,•, D.J.1994. Computerized tools forparticipatory naBecause sense ofplaceisnotthesole tional forest planning. Journal ofForestry 92(2):3740. province ofanyonegroup,interest, or DRIVER,B.L., C.J.MANNING,andG.L. PETERSON. philosophy, it doesnotnecessarily give 1996.Toward better integration ofthesocial andbiocomponents ofecosystems management. In thosewhodislikea proposed change physical Natural resource management: The human dimension, new powerto stopit (althoughthe ed.A. Ewert,109-27. Boulder,CO: WestviewPress. powerof language cannotbedenied). FORCE, J.E.,andG. M•CHLIS. 1997.Thehumaneco- Environmental activists who advocate The Context system partII: Social indicators in ecosystem man- of Resources agement. Society andNatural Resources 10:347-67. changing theappearance of a placeto GROAT, L., ed. 1995. Giving places meaning: Readings in Sense of placeandecosystem man- restore ecosystem healthmaydojustas environmentalpsychology. SanDiego: Academic Press. agement havemuchin commonasre- muchto violate people's sense of place GRUMBINE, R.E.1992.Ghost bears: Exploring thebiodisponses to the historically dominant asthetimbercompany thatclearcuts a versity crisis. Washington, DC:Island Press. D. 1996. Justice, nature andthegeography ofd• utilitarianism thathasguidedresource favoritevista.Nor is the conceptal- HARVEY, London: Blackwell. managementsince Pinchot'stime. waysusedto prevent change: historic j•rence. R.1985.Subconscious landscapes oftheheart. Bothconcepts recognize thatsociety restorationoften involvesmaking HESTER, Places 2(3):10-22. valuesnaturalresources in waysnot changes for thesakeof enhancing or LARSON, G., A. HOLDEN, D. KAPALDO, J. LEASURE, J. MASON, H. SALWASSER, S.YONTS-SHEPARD, andW.E. easilyor necessarily capturedby the re-creating a sense of place. SH^NDS. 1990.Synthesis ofthecritique oflandmancommodity andproduction metaphors Sense of placeisnota newlanduse Policy Analysis StaffPublication of "use" and"yield."Bothtry to local- or a setof rightsbuta wayof express- agementplanning. FS-453. Washington, DC:USDAForest Service. izeandcontextualize knowledge. Both inga relationship between peopleand MANDER, J., andE. GOLDSMITH, eds.1996.Thecase pay attentionto historyand geo- a place.The problemisn'tto consider against theglobal economy: Andj•r a turntoward the local.SanFrancisco: SierraClub Books. graphicscale. everyindividual's particularsenseof S.E,andS.R.M•a•TIN. 1994.Community atRecognizingthe processes and place,butratherto recognize thatin McCOoL, tachment andattitudes toward tourism development. meaningsthat constitutesenseof planningprocesses andmanagement Journal ofTravel Research 22(3):29-34. place,however,addsa significant decisionmaking, the toolsmanagers MITCHELL, M.Y.,J.E.FORCE, M.S.C•mOLL, andW.J. MCLAUGHLIN. 1993.Forest places oftheheart: Inhumanrolein makingandusingthe useto represent thequalities of a place corporating special places intopublic management. landscape without reducing humans to often limit what is considered. But Journal ofForestry 91(4):32-37. onespecies amongmany.Negotiating givennaturalresource managers' pen- R•LPH, E. 1997.Sense ofplace. In 7•ngeographic ideas toolsandtechnical a shared sense of placethatincorpo- chantfor analytical thatchanged theworl•edS.Hanson, 205-26.New NJ:Rutgers University Press. ratesbothnaturalandsocial history al- analyses, thereisa danger in thinking Brunswick, EB.,andE L. K•O?F. 1996.Putting "ecosyslowsmanagers opportunityto find ofsense ofplaceassimply another vail- SAMSON, tem"intonatural resource management. Journal of common groundwithoutpigeonhol- ableor resource descriptor to round SoilandWater Conservation July-August:288-92. ing peopleinto utilitarian,environ- out ecosystems assessments. SCHROEDER, H.W.1996.Ecology oftheheart: Undermentalist, or romantic preservationist Understanding standing howpeople experience natural environments. senseof placereInNatural resource management: The human dimension, positions. Thatis,it maybepossible to minds us that natural resourcesexist in ed.A. Ewert,13-27.Boulder, CO:Westview Press. build a level of consensusaround sense a social andpoliticalworld.Virtually Sl•vlaI,S.1991.Sense ofplace: Anempirical measureof placebecause it readilyleadsto a anyresource or land-use planning efment.Geoj•rum 22:347-58. discussionof desiredfuture conditions fort is reallya publicexercise in de- SPRETNAK, C. 1997.Theresurgence ofthereal: Body nainahypermodern world. NewYork: Adof a resource in bothecological and scribing, contesting, andnegotiating tureandplace dison-Wesley. human terms. competing senses of placeand ulti- TUAN, Y.-E1977.Space andplace: The perspective ofexThe termitselfis neutral,though matelyworkingout a sharedfuture perience. Minneapolis: University ofMinnesota Press. the venues in which it is used are often sense of place.That, in essence, is the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE oftheInterior Columbia Basin: highlychargedevidence ofthepower centralobjectiveof naturalresource (USDA).1996.Status Summary ofscientific findings. General Technical Reof the ideasit expresses. Concerns planning, andit maybetheonlygenport385.Portland, OR:USDAForest Service, Paaboutsense of placeshouldsignalto uinelyintegrative approach to manag- cificNorthwestResearchStation. managers thatthesocialcostsassoci- ing ecosystems. Wlkt•MS, B.A., andA.R. M•T•At•.1995. Democrm> dialogue, andenvironmental dirputes: The contested languages atedwith a proposed course of action ofsodal•gulation. NewHaven, CT:Yale University Press. maybehigh.What themanager can Literature Cited andshould doin response maybelim- AGNEW, J.A.,andJ.S.DUNCAN. 1989.Thepower of Bringing together geographical andsociological itedbyexisting institutional structures place: or rules, but the sentiments and processes of sense of placecannotbe avoided simplybecause existing planning toolsandruleshavetendedto favortechnical analyses. Societal interestin sense of placemay,in thelong run,inspirereforms of resource planninglawsandprocedures that better imaffnations. Boston: UnwinHyman. A•TMA•,I., andS.M. Low,eds.1992.Placeattachment. Human behavior andenvironment:Advances intheory andresearch, vol.12. New York:PlenumPress. Daniel R. •lliams (e-mail:d-willil @ uiuc. edu)isassociate proj•ssor, Departmentof Leisure Studies, University of APPLEYAIm, D. 1979.Theenvironment asasocial symbol: Illinois, 1206 South Fourth Street, Within atheory ofenvironmental action andpercep- Champaign 61820;Susan L Stewart is tion.American PlanningAssociation Journal53:143-53. researchsocial scientist, USDA Forest B•NDENBURG, A.M., andM.S. C/mROLL. 1995.Your North CentralForest Experiplace, ormine: Theeffect ofplace creation onenvi- Service, ronmental values andlandscape meanings. Society ment Station,Evanston,Illinois. Journalof Forestry 23

![Word Study [1 class hour]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007905774_2-53b71d303720cf6608aea934a43e9f05-300x300.png)