AILACTE Journal The Journal of the Association Of Independent Liberal Arts Colleges

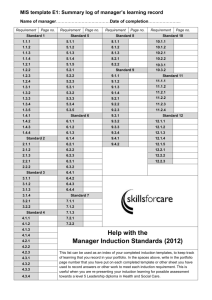

advertisement