Overview on the Diversity of ... Clownfishes (Pomacentridae): Importance of Acoustic

advertisement

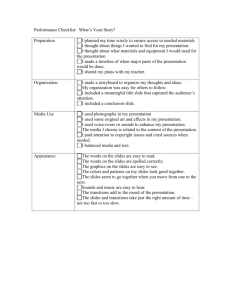

© PLOSI o OPEN 3 ACCESS Freely available online - Overview on the Diversity of Sounds Produced by Clownfishes (Pomacentridae): Importance of Acoustic Signals in Their Peculiar Way of Life Orphal Co 11eye", Eric Parm entier Laboratory of Functional and Evolutionary Morphology, University of Liège, Liège, Belgium Abstract Background: Clownfishes (Pomacentridae) are brightly colored coral reef fishes well known for their mutualistic symbiosis with tropical sea anem ones. These fishes live in social groups in which there Is a size-based dom inance hierarchy. In this structure w here sex is socially controlled, agonistic interactions are num erous and serve to maintain size differences betw een Individuals adjacent In rank. Clownfishes are also prolific callers w hose sounds seem to play an im portant role in the social hierarchy. Here, we aim to review and to synthesize the diversity of sounds produced by clownfishes In order to emphasize the Importance of acoustic signals In their way of life. M ethodology/Principal Findings: Recording the different acoustic behaviors Indicated th at sounds are divided Into two main categories: aggressive sounds produced In conjunction with threat postures (charge and chase), and submissive sounds always emitted w hen fish exhibited head shaking m ovem ents (I.e. a submissive posture). Both types of sounds show ed size-related Intraspeclflc variation In d om inant frequency and pulse duration: smaller Individuals produce higher frequency and shorter duration pulses th an larger ones, and inversely. Consequently, th ese sonic features might be useful cues for individual recognition within th e group. This observation Is of significant Importance d ue to th e size-based hierarchy In clownflsh group. On th e o ther hand, no acoustic signal was associated with th e different reproductive activities. Conclusions/Significance: Unlike o th er p o m a ce n tru s , sounds are not produced for m ate attraction In clownfishes but to reach and to defend th e competition for breeding status, which explains why constraints are not Im portant e n o u g h for promoting call diversification In this group. C itation : Colleye O, Parmentier E (2012) Overview on th e Diversity of Sounds Produced by Clownfishes (Pomacentridae): Importance of Acoustic Signals in Their Peculiar Way o f Life. PLoS ONE 7(11): e49179. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049179 Editor: Stephan C. F. Neuhauss, University Zürich, Switzerland Received August 31, 2012; A ccepted October 9, 2012; Published November 7, 2012 C opyrigh t: © 2012 Colleye, Parmentier. This is an open-access article distributed under th e term s of th e Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided th e original author and source are credited. Funding: This research was supported by th e Takeda Science Foundation and a 21st Century Center o f Excellence project entitled "The Comprehensive Analyses on Biodiversity in Coral Reef and Island Ecosystems in Asian "Concours des bourses d e voyage 2009" from "Ministère d e Fondam entale Collective (FRFC) (no. 2.4.535.10.F) delivered FNRS (Bourse d e Doctorat F.R.S.- FNRS). The funders had manuscript. and Pacific Regions" from th e University of the Ryukyus via a Visiting Fellowship, by a grant entitled la C om m unauté française d e Belgique" attributed to OC, and by a grant from Fonds d e la Recherche by th e Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research. OC was supported by a grant from th e F.R.S.no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the C om peting Interests: The authors have declared th a t no com peting interests exist. * E-mail: 0.Colleye@ulg.ac.be from two different so und-producing m echanism s [9]. T h e L usitanian toadfish Halobatrachus didactylus p roduces the boatw histle advertisem ent call th a t is related to the b reed in g season a n d at least three o th er sounds d u rin g agonistic encounters: grunts, croaks a n d double croaks [10,11], D am selfishes (Pom acentridae) a re one o f the best-studied families for the use o f acoustic com m unication d u rin g courtship a n d agonistic interactions, w ith som e species such as Dascyllus albisella a n d D . flavicaudus show ing a g reat diversity a n d com plexity in their acoustic repertoire. T h e y are know n to p ro d u c e pulsed sounds d u rin g n um erous behaviors including signal ju m p , m a tin g / visiting, chasing conspecifics a n d heterospecifics, fighting conspecifics a n d heterospecifics, a n d nest cleaning [12,13]. All these sounds seem to b e constructed on the basis o f the sam e m echanism since they display the sam e type o f sound spectrum a n d show few differences in term s o f pulse d uration. O n the o th er han d , differences in the n u m b e r o f pulses a n d pulse p e rio d could b e due Introduction In teleost fishes, the ability to pro d u ce sounds was developed independently in d istant phylogenetic tax a [1], T o date, m ore th an 100 fish families include species w ith the ability to em it sounds [2,3]. T h e m ajority o f acoustic signals are used in different behavioral contexts such as aggressive b eh av io r (territorial defense, p re d a to r/p re y interactions, com petitive feeding) o r reproductive activities (m ate identification a n d choice, courtship, synchroniza­ tion o f gam ete release) [2,4,5]. T h e diversity o f sounds p ro d u c ed by fishes is not as rem arkable as in o th er taxa; m ost fishes show p o o r am plitude a n d frequency m odu latio n in th eir sounds [6,7,8] a n d have relatively lim ited acoustic repertoires. O nly few fish species em it m ore th a n one or two distinct sound types. H ow ever, the calling characteristics provide sufficient inform ation for species identification a n d com m unication. F or exam ple, the rainbow cichlid Herotilapia multispinosa em its four distinct sound types (thum ps, growls, whoofs a n d volley sounds) th a t w ould result PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org 1 N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes to the fish physiology reflecting the b ehavior a n d its m otivational state [13]. C lownfishes (Pom acentridae) live in social groups in w hich there is a size-based dom in an ce hierarch y [14,15]. W ithin each group, n um erous agonistic interactions occur a n d they a p p e a r to play an im p o rta n t role by m ain tain in g size differences b etw een individuals ad jacen t in ra n k [14,15]. Intraspecific encounters are com m on a n d som etim es ra th e r severe in th eir intensity. L arger fishes chase sm aller ones, w hich m eans th a t the sm allest one is the recipient o f n um erous charges [15]. All clow nfish species have evolved ritualized th rea t a n d submissive postures th a t p resum ably serve to circum vent physical injury d u rin g intraspecific q u arrelin g [16], F or exam ple, the “ h e a d shaking” is considered as a submissive state exhibited by fish in reactio n to aggressive interactions [16,17,18], T his b ehavior consists in a lateral quivering o f the body th a t begins a t the h e a d a n d continues posteriorly. C lownfishes are know n to p ro d u c e aggressive sounds while displaying charge a n d chase tow ards a n o th e r specim en du rin g agonistic interactions [16,18,19], M o re recently, Colleye et al. [20] cond u cted furth er studies o n aggressive sounds in the skunk clownfish Amphiprion akallopisos; they highlighted a size-related intraspecific v a riation in d o m in a n t frequency a n d pulse duration: sm aller individuals p ro d u c e h igher frequency a n d shorter d u ra tio n pulses th a n larger ones. Surprisingly, the relationship b etw een fish size a n d b o th d o m in a n t frequency a n d pulse d u ra tio n is not only species-specific. T hese relationships are also spread out over the entire tribe o f clownfishes b y bein g found am o n g 14 different species th a t are situated o n exactly the sam e slope, w hich m eans the size o f any Amphiprion can be p red icted b y b o th acoustic features [21]. Besides these aggressive sounds, S chneider [18] d o c u m e n ted a second type o f sound th a t was associated w ith “ h e a d shaking” a n d was em itted b y fishes in conjunction w ith submissive posture. L ater, Allen [16] re p o rte d the presence o f h e a d shaking m ovem ents associated w ith sound em ission du rin g agonistic interactions betw een group m em bers. L hifortunately, the lack o f detailed acoustic d a ta a n d the small sam ple sizes o f the behavioral observations require fu rth er investigations to differentiate these sounds from aggressive ones a n d to b e tte r u n d e rstan d the scope o f these acoustic signals w ithin a social group o f clownfishes. A dditionally, it was re p o rte d th a t clownfishes m ight pro d u ce sounds d u rin g courtship. C ourtship in clownfishes is generally stereotyped a n d ritualized, a n d is typically a cco m p an ied by different activities such as nest cleaning, courtship, spaw ning a n d nest care [16], Basically, studies th a t describe the courtship sounds in clownfishes are lim ited in nu m b er. T o date, sound pro d u ctio n d u rin g reproductive p e rio d has b e en re p o rte d in three clownfish species (A. ocellaris, A . frenatus, A . sandaracinos) by T a k e m u ra [22]. H ow ever, these observations need to be carefully considered since, a ccording to the au th o r, the sounds w ere h a rd ly h e a rd a n d som etim es they do n o t seem to b e directly related to spaw ning b ehavior [22]. T herefore, d eeper a tten tio n m ust b e p a id to confirm the im plication o f acoustic signals d u rin g rep ro d u c tio n in this group. T h e presen t study aim s to review a n d to synthesize the diversity o f sounds p ro d u c ed by clownfishes in o rd e r to em phasize the im p o rtan ce o f acoustic signals in th eir w ay o f life. T h e purpose o f this study is 1) to reco rd a n d to analyze sounds associated w ith h e a d shaking in o rd e r to determ in e their role in the social structure o f clownfishes; 2) to determ in e w h e th er clownfishes use acoustic signals to synchronize one o r several o f their reproductive activities a n d 3) to m ake fu rth er analyses o f som e results previously obtain ed for the aggressive sounds (see [20]) w ith the aim o f determ ining w h eth er som e acoustic features m ay c ontribute to individuality. PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org M aterials and Methods D ifferent species a n d different types o f d a ta w ere collected in fish tanks a n d in the field w ith the aim o f covering all the behaviors th a t could be associated w ith sound p ro duction. E x p erim ental a n d anim al care protocols follow ed all relevant intern atio n al guidelines a n d w ere ap p ro v ed by the ethics com m ission (no. 728) o f the Lhiiversity o f Liège. Agonistic sounds T h re e groups bein g each com posed o f four individuals o f L ength, SL: 4 4 -1 1 2 nini) w ere collected by scuba diving o n the fringing re e f a ro u n d N akijin village (2 6"40'N - 127"59'E ; O kinaw a, Ja p a n ) d u rin g M ay a n d J u n e 2009. All fish w ere th en b ro u g h t back w ith their host (Entacmaea quadricolor) to Sesoko Station, T ro p ical Biosphere R esearch C enter, Lhiiversity o f the R yukyus w here they w ere transferred to a c om m unity tan k (3.5 x 2 .0 x 1.2 m) filled w ith ru n n in g seaw ater at am b ien t tem p e ra tu re (28 to 30.5"C). All fish w ere kept u n d e r n a tu ra l p h o to p erio d a n d fed once daily w ith food pellets ad libitum. T h e social ra n k o f each individual was attested using size differences. Basically, groups w ere com posed o f a b re ed in g p a ir a n d two n on-breeders (T able 1). R ecordings w ere m ad e in a sm aller glass tan k (1 .2 x 0 .5 x 0 .6 m) filled w ith ru n n in g seaw ater m ain tain ed a t 28"C by m eans o f a G E X cooler system (type G X C -2 0 1 x , O saka, Ja p a n ) for having standardized conditions. F o r the sound recordings, all individuals o f a group a n d th eir host w ere first p lac ed in the tan k for an acclim ation tim e o f 2 days. T w enty sessions (each lasting a ro u n d 45 m inutes) w ere re co rd e d du rin g w hich interactions betw een group m em bers w ere observed a n d n o ted in o rd e r to identify the sound em itter. O nly sounds associated w ith h e ad shaking m ovem ents w ere taken into account in the analyses because the aim o f this p a rt was to give a concise physical description o f this type o f sounds in o rd e r to co m p are it w ith clow nfish aggressive sounds (see [20,21,23]). S ound recordings w ere m ad e using a B rüel & K ja er 8106 hy d ro p h o n e (sensitivity: —173 dB re. 1 V /p P a ) con n ected via a N e x u s™ conditioning am plifier (type 2690) to a T asca m H D -P 2 stereo audio reco rd e r (recording b andw ith: 20 H z to 20 k H z ± 1 .0 dB). T h i system has a flat frequency response over w ide range b etw een 7 H z a n d 80 kH z. T h e h y d ro p h o n e was placed ju st above the sea an em o n e (± 5 cm). Sounds w ere digitized at 44.1 k H z (16-bit resolution) a n d analysed w ith AviSoft-SA S L ab P ro 4.33 software (1024 point H a n n in g w indow ed fast F o u rrie r transform (FFT)). R eco rd in g in small tanks induces poten tial hazards because o f reflections a n d tan k resonance [24], A relevant e q u atio n [24] was thus used to calculate the re so n an t frequency o f the tank, a n d a low pass filter o f 2.05 k H z was applied to all sound recordings. T em p o ral Amphiprion frenatus (S tandard Table 1. Standard length (SL) and size order in the different groups of Amphiprion frenatus. Size ord e r a(female) SL (m m) G rou p 1 G rou p 2 G rou p 3 105 110 112 83 ß(male) 76 81 y(non-breeder) 63 65 75 S(non-breeder) 44 50 53 doi:10.1371 /journal.pone.0049179.t001 2 N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes features w ere m easured from the oscillogram s w hereas frequency p a ram ete rs w ere o b tain e d from pow er spectra (filter b an d w id th 300 H z, F F T size p o in t 256, tim e overlap 96.87% a n d a flat top window). G enerally speaking, the reco rd ed sounds w ere com posed o f a series o f sounds bein g m ultiple-pulsed. T h e follow ing sonic features w ere m easured: pulse d u ra tio n in ms, pulse p e rio d in ms (the average peak to peak interval b etw een consecutive pulse units in a series), n u m b e r o f pulses p e r sound, sound d u ra tio n in ms, sound p e rio d in m s (the average p eak to peak interval betw een consecutive sounds in a train), n u m b e r o f sounds p e r tra in a n d d o m in a n t frequency in H z (frequency c o m p o n en t w ith the m ost energy). N ote th a t sounds p ro d u c ed sim ultaneously b y several individuals w ere excluded from acoustic analyses. social ra n k is the g rouping factor. Secondly, sonic variables not co rrelated w ith SL, w hich failed the test for n o rm al distribution (Shapiro-W ilk W Test), w ere analyzed using a n o n -p aram etric K ruskal-W allis one-w ay A N O V A by ranks w ith subsequent D u n n ’s test for pair-w ise com parisons to test differences betw een social ranks. All statistical analyses w ere c arried o u t w ith Statistica 7.1. R esults are presen ted as m eans ± sta n d ard deviation (S.D.). Significance level was d e term in ed a t ƒ><().05. M e a n ± S.D . values w ere calculated for each acoustic feature o f agonistic sounds for all individuals. O verall m eans, S.D . a n d range values w ere subsequently calculated using each individual m ean value for each variable. In o rd e r to co m p are betw een-individuals w ith w ithin-individuals variability for each acoustic feature, the w ithin-individuals coefficient o f v ariance (C.V.W= S .D ./m ean) was calculated a n d c o m p a red w ith the betw een-individuals coefficient o f variation (C.V.b). T h e C.V.b was o b tain e d by dividing the overall S.D . by the respective overall m ean. T h e ratio C .V .b / C.V.Wwas th en calculated to o b tain a m easure o f relative betw eenindividuals variability for each acoustic feature. W h en this ratio assum es values larger th a n one, it suggests th a t a n acoustic feature could be used as a cue for individual recognition [25,26,27]. Differences betw een individuals for each acoustic variable w ere tested using a K ruskal-W allis analysis due to the lack o f hom ogeneity o f variance. N ote th a t this statistical test was ru n betw een individuals from a sam e group in the case o f submissive sounds. In addition, this test was also ru n b etw een the 14 individuals o f the skunk clow nfish Amphiprion akallopisos for w hich aggressive sounds w ere previously re co rd e d (see [20]), in o rd e r to determ in e if som e acoustic features m ay con trib u te to individu­ ality. Reproductive sounds R ecordings w ere m ad e b o th in a q u ariu m a n d in the field. In captivity, three species (A. akyndinos, A . melanopus a n d A. ocellaris) re are d for several years a t O ceanopolis A q u ariu m in Brest (France) w ere re co rd e d d u rin g Ju ly 2008. O n e m atin g p a ir p e r species was studied. E ac h m atin g p a ir was m ain tain ed in separate glass tanks (0 .7 0 x 0 .4 5 x 0 .5 0 m) filled w ith ru n n in g seaw ater at am b ie n t te m p e ra tu re (26°C). T h e different reproductive activities (nest p re p ara tio n , courtship, spaw ning a n d eggs care) w ere observed a n d recorded. E ach reco rd in g session lasted ap p ro x i­ m ately 2 h, a n d four reco rd in g sessions w ith a 1-hour interval w ere carried o u t b y day in o rd e r to cover the w hole daytim e from daw n to dusk. B ehaviors o f m ale a n d fem ale w ere observed a n d noted. In addition, recordings in captivity w ere also m ad e in Sesoko Station. O n e m atin g p a ir o f A . clarkii was kept in a tank (1.2 x 0.5 x 0 .6 m) filled w ith ru n n in g seaw ater m ain tain ed at 28°C . R ecordings w ere carried o u t du rin g sum m er season 2009 (betw een M ay a n d July) because rep ro d u ctio n is lim ited to this p erio d w h en seaw ater tem p eratu res are w arm er. In b o th cases, sound recordings w ere m ad e using the sam e Brüel & K ja e r 8106 hy d ro p h o n e (see above for details o n m aterial characteristics), a n d sounds w ere analyzed a ccording to the p ro ced u re previously described. Field recordings w ere m ad e on the fringing re e f in front o f H izuchi b eac h (2 6 °1 1 'N - 127°16'E ; A kajim a, K e ra m a Islands, Ja p a n ) in A ugust 2009. T h ey w ere m ad e using a S O N Y H D D video c am era p lac ed in a housing (H C 3 series) coupled w ith an external h y d ro p h o n e (High T ech . Inc.) w ith a flat response o f 20 H z to 20 k H z a n d a n om inal calibration o f —164 dB re. 1 V / p P a (L oggerhead Instrum ents Inc.). R ecordings w ere m ade by placing the housing in front o f the in h ab ited sea an em o n e (distance o f betw een 50 cm a n d 1 m) th a t lived a t a d e p th o f betw een 5 m a n d 10 m . E ach reco rd in g session lasted from 1 to 4 h. B ehaviors associated w ith sound p ro d u c tio n w ere described a n d sounds w ere ex tracted in .wav files using the A oA audio e xtractor setup freew are (version 1.2.5). S ounds w ere digitised a t 44.1 kH z (16-bit resolution), low-pass filtered a t 1 k H z a n d analysed using AviSoft-SA S L ab Pro 4.33 software (1024 p o in t H a n n in g w indow ed fast F o u rrie r T ran sfo rm (FFT)). O n ly sounds w ith a good signal to noise ratio w ere included in the analyses. Results Agonistic sounds Subm issive sounds w ere always associated w ith h e ad shaking m ovem ents (Fig. 1), b u t fish could som etim es carry o u t these m ovem ents w ith o u t vocalizing. Subm issive sounds (jV= 285 sounds analyzed for all individuals o f the different groups; see T ab le 2) w ere p ro d u c ed w h en subordinates displayed submissive p osture as a reactio n to charge a n d chase by dom inants, w hich m eans th a t these sounds w ere never re co rd e d for the d o m in a n t females (rank 1) d u rin g this study. G enerally speaking, submissive sounds are com pletely different from aggressive ones. T h ey are always com posed o f several pulses w hereas aggressive sounds are com posed o f a single pulse un it th a t can b e em itted alone o r in series (Fig. 2). T h ey also exhibit shorter pulse periods a n d shorter pulse d urations th a n aggressive sounds. In A . frenatus, submissive sounds can be p ro d u c ed alone o r in series (2-9 sounds, 3 .0 ± 0 .5 6 ), a n d are m ultiple-pulsed (2 -6 pulses, 3 .2 ± 0 .2 6 ). Pulse p erio d averaged 1 1 .8 ± 2 .4 m s a n d pulse d u ra tio n ra n g ed from 4.7 to 10.3 ms (7 .9 ± 2 .1 5 ms). S ound p e rio d averaged 197.0 =±26.6 ms a n d sound d u ra tio n ra n g ed from 23.5 to 50.6 m s (3 5 .9 ± 9 .5 9 ms). Pulses h a d p eak frequency o f 591 ± 115 H z a n d m ost sound energy ra n g ed from 454 to 778 H z. D o m in a n t frequency a n d pulse d u ra tio n w ere highly co rrelated w ith SL. D o m in a n t frequency significantly decreased (R = —0.98, j&< 0.0001 ; Fig. 3A) w hereas pulse d u ra tio n significantly increased (R = 0.98, j6<0.0001; Fig. 3B) w ith increasing SL. Pulse p e rio d was co rrelated across SL (R = 0.96, j6<0.0001; Fig. 3C) a n d this sonic variable was also significantly co rrelated w ith pulse d u ra tio n (R = 0.95, p = 0.0001). A dditionally, sound d u ra tio n was co rrelated w ith increasing SL (R = 0.97, /)< 0 .0 0 0 1 ; Fig. 3E); this acoustic feature bein g also significantly co rrelated w ith b o th pulse d u ra tio n (R = 0.93, p = 0.0003) a n d pulse p e rio d (r= 0 .9 8 , j&CO.OOOl). Statistical analyses C orrelations analyses w ere used to exam ine changes in all acoustic features o f submissive sounds across SL. T h e d a ta used in these analyses w ere m ea n values o f all reco rd ed sounds for each individual. T w o statistical analyses w ere th e n p erfo rm ed to test the influence o f social ra n k on sonic features. First, a full A N C O V A was ru n to test differences b etw een social ranks (ß, y, 8; see T ab le 1) for the sonic variables co rrelated w ith SL. In this test, sonic variables are considered as variâtes, SL as a covariate a n d PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org 3 N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes strong hom ogeneity o f these variables. All the acoustic features analyzed h a d C .V .b/C .V .w r a tio s > l, show ing a h igher variability a m o n g th a n w ithin individuals. C onsistently, the K ruskal-W allis analyses revealed significant differences am o n g individuals for alm ost all features (Tables 4, 5), in dicating th a t these acoustic variables (except the n u m b e r o f pulses p e r sound a n d the n u m b er o f sounds p e r train in groups 1 a n d 2 o f A . frenatus', T ab le 5) can potentially provide recognition cues to identify the sound em itter. T h e larg er relative betw een-individuals variability (larger C .V .b/ C.V.W ratios) c o rresponded to the d o m in a n t frequency, pulse d u ra tio n a n d pulse p e rio d (Tables 4, 5). B Reproductive sounds A total o f eight spaw ning events w ere observed. All reproductive p attern s including nest p re p ara tio n , courtship, spaw ning a n d p a ren tal care w ere once observed a n d reco rd ed in -4. akindynos, -4. melanopus a n d -4. percula d u rin g J u ly 2008 a t O ceanopolis A quarium . Amphiprion clarkii spaw ned four tim es betw een M ay a n d Ju ly 2009 in Sesoko Station, a n d all the reproductive activities w ere observed a n d recorded. Spaw ning always o ccu rred in the a fternoon from 2:00 to 5:00 p .m ., w hatever the species. In addition, one com plete spaw ning sequence in -4. perideraion was observed a n d recorded in the field for a pproxim ately 80 m inutes in A ugust 2009 (11:20 to 12:40 a.m .). O verall, the m ost striking observation was the com plete absence o f sound p ro d u c tio n th ro u g h o u t all activities o f the reproductive p e rio d in the different clow nfish species recorded, a n d w hatever the reco rd in g env iro n m en t (aquarium o r field). H ow ever, some o th er typical behaviors seem to b e responsible for the synchroni­ zation o f the reproductive activities. F ig u re 1. B e h a v io ra l p o s t u r e s a s s o c ia t e d w ith v o c a liz a t io n s a n d e x h ib ite d b y Amphiprion frenatus d u r in g a g o n is t ic in te r a c ­ t io n s . A) D o m in a n t in d iv id u al c h a s in g s u b o rd in a te w h ile p ro d u c in g a g g r e s s iv e s o u n d s . B) H e a d s h a k in g m o v e m e n ts d is p la y e d b y s u b o r d in a te w h ile p ro d u c in g s u b m is s iv e s o u n d s in re a c tio n to a g g re ss iv e a c t b y d o m in a n t. N o te th a t w ig g ly lines in d ic a te th e s o u n d -p ro d u c in g in d iv id u al, a n d a rro w s p o in t o u t th e re c e iv e r o f th e a g g re ss iv e act. Likewise, sound p e rio d was co rrelated w ith increasing SL (R = 0.86, p = 0.0031; Fig. 3F), bein g significantly co rrelated w ith sound d u ra tio n (i? = 0.82, p = 0.0063). T h e n u m b e r o f pulses p e r sound did n o t change significantly (R = 0.10, p = 0.7917; Fig. 3D) across SL, as well as the n u m b e r o f sounds p e r train (i? = 0 .0 6 , p = 0.8686; Fig. 3G). A com parison o f social ra n k values using SL as a covariate show ed th a t the d o m in a n t frequency (ANC O V A , test for com m on slopes: F 3) = 3.677, p = 0.156; test for intercepts: F,25)= 1.204, p = 0.374) a n d pulse d u ra tio n (A N C O V A , test for co m m o n slopes: F,2 3) = 3.644, p = 0.175; test for intercepts: F,2 5) = 4.204, p = 0.137) did not differ betw een individuals o f different social ranks. T h ereb y , differences betw een social ranks in these acoustic features exclusively resulted from size differences. In addition, the influence o f fish size on acoustic features was en h an c ed by co m p arin g th em betw een individuals o f the sam e social ra n k b u t from different groups. All the acoustic features w ere significantly different betw een individuals o f the sam e ra n k (T able 3), except w hen these ones h a d sim ilar SL. In this case, acoustic features did not differ (D u n n ’s test, />>0.05). K ruskal-W allis one-w ay A N O V A revealed th a t m eans w ere significantly different b etw een social ranks for pulse p erio d (H = 6.489, d f = 2 , p = 0.0390) a n d sound d u ra tio n (H = 7.200, d f= 2, p = 0.0273), b u t not for sound p e rio d (H = 3.822, d f= 2, p = 0.1479), n u m b e r o f pulses p e r sound (H = 1.898, d f= 2, p = 0.3871) a n d n u m b e r o f sounds p e r train (H = 2.508, d f= 2, p = 0.2853). Pairw ise com parisons show ed th a t pulse p erio d a n d sound d u ra tio n w ere h igher in ra n k 2 (D u n n ’s test, /><0.05; T ab le 2) th an in ra n k 4, w hereas no significant differences w ere observed betw een ranks 2 a n d 3 (D unn’s test, />>0.05; T ab le 2), a n d betw een ranks 3 a n d 4 (D u n n ’s test, />>0.05; T ab le 2) due to considerable overlap. Aggressive a n d submissive sounds presen ted som e acoustic features th a t displayed C .V .W^ 0 .1 0 (Tables 4, 5), suggesting a 1. T h e arrival o f spaw ning p erio d was indicated by a n increase o f cleaning activity b y the m ale, a n d by the belly o f the fem ale th at was noticeably distended (especially in -4. percula a n d -4. perideraion). T hese features b e cam e usually distinct three o r four days before spaw ning. O ccasionally, fish chased each a n o th e r o r engaged in fast side-by-side sw im m ing a n d belly touching; the fem ale being the initiator in m ost o f these encounters. Som etim es, the fem ale e n te red the nest a n d pressed h e r belly against the rock (spaw ning ground). Pecking m ovem ent o f the m ale at the surface o f nest becam e m o re vigorous from ab o u t two hours before spaw ning; this m ovem ent was con tin u ed until ju st before spaw ning. A bout 15 m inutes before spaw ning, nest-cleaning activities was m ore rigorously carried o u t b y the fem ale, w hich pecked the surface o f the spaw ning g round. Also, she pressed h e r belly against the substrate. T hese activities seem ed to aim a t m aking sure o f the com pletion o f the spaw ning g round. A t the onset o f spaw ning, the w hitish cone-shaped ovipositor o f the fem ale was clearly ap p are n t. 2. T h e spaw ning was carried out in the follow ing way: the fem ale e n te red the nest, pressed h e r belly against th e spaw ning gro u n d a n d sw ani slowly in a circular p ath; the m ale followed closely b e h in d a n d fertilized the spawn. L ocom otion d u rin g the spaw ning passes was achieved b y ra p id fluttering o f the pectoral fins. T h e m ale frequently m o u th e d the eggs d u rin g the spaw ning period. B oth fish also nib b led o n the tips o f the an em o n e tentacles for p reventing the spaw n from en terin g into con tact w ith them . 3. A fter the spaw ning, the incubation p e rio d took place a n d was ch aracterized by p a ren tal care, w hich lasted usually six to seven days. T h e m ale assum ed nearly the full responsibility o f tending the nest. E xcept a n initial m o d erate level o f activity a t spaw ning, th ere w ere no cleaning activities the first two days. T h en , an ab ru p t increase o ccu rred the next few days until hatching. T w o basic nest-caring beh av io r p a tte rn s w ere observed. F a n n in g was the m ost c om m on a n d was m ainly p erfo rm ed b y fluttering the pectoral fins. M o u th in g the eggs a n d substrate biting a t the ,2 PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org 4 N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes 1—1 -12 N ----- > I >, o <D 3 iL m i ni i i'nM ! i Wl'I Wlí1ifi m 'lii' b i l l i Uii1 Ur Ei I I il 3 CT" I[J-. till ¿ i 'í í l ü in in i'Ü in 1'tPlm liiUnJW <L> 1 20 60 « i i è iili 100 140 180 220 260 300 340 380 420 460 500 540 Time (ms) B > — ■ S 80 ^ i 1 - -------------------------------------------i H 40 & Enj <L> -40 > A-t -80 nj "ÖJ N M 3 o C 2 3 1 er 2 tu V W 20 60 100 140 180 220 260 300 340 380 420 Time (ms) F ig u re 2 . E x a m p le o f a g o n is t ic s o u n d s p r o d u c e d b y A m p h ip rio n fre n a tu s d u r in g in te r a c tio n s . A) O scillo g ram (to p ) a n d s p e c tro g r a m (b o tto m ) o f su b m iss iv e s o u n d s p ro d u c e d b y s u b o rd in a te d u rin g h e a d s h a k in g m o v e m e n ts . B) O scillo g ram (to p ) a n d s p e c tro g r a m (b o tto m ) o f a g g re ss iv e s o u n d s p r o d u c e d b y d o m in a n t w h ile d isp la y in g c h a r g e a n d c h a s e . N o te th e d iffe re n c e s in (1) p u ls e d u ra tio n a n d (2) p u ls e p e rio d . T he a c o u s tic v a ria b le m e a s u re d in (3) r e p re s e n ts th e s o u n d d u ra tio n in th e c a s e o f su b m iss iv e s o u n d s , a n d th e tra in d u ra tio n in th e c a s e o f a g g re ss iv e s o u n d s . T he c o lo u r sca le c o rre s p o n d s to th e in te n s ity a ss o c ia te d w ith th e d iffe re n t fre q u e n c ie s. d o i:1 0 .1 3 7 1 /jo u rn a l.p o n e .0 0 4 9 1 7 9 .g 0 0 2 Discussion p e rip h e ry o f the nest w ere also exhibited. D e a d eggs w ere regularly rem oved as indicated by b a re patches a t the nesting surface. In clownfishes, different types o f sounds such as “th rea te n in g ” a n d “ shaking” [18], “ click” a n d “g ru n t” [16] o r “ p o p ” a n d “ c h irp ” [19,23] have already b e en described du rin g interactions PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org 5 N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes betw een conspecifics. A lthough a dichotom y in sounds was re p o rte d in each case, these term s have b e en inconsistently applied a n d w ere n o t always supported by ap p ro p ria te d a ta w hich create confusion [10], C onsequently, it re m a in e d difficult to m atch a type o f sound w ith a given behavior. H ow ever, o u r m ultiple observations highlight th a t submissive sounds (i.e. chirps, see [23]) are clearly different from aggressive sounds (i.e. pops, see [23]). Aggressive sounds are m ainly p ro d u c ed by dom inants du rin g chases a n d th rea t displays b etw een conspecifics [20], w hereas submissive sounds are always em itted w h en subordinates exhibit h e a d shaking m ovem ents in reactio n to aggressive displays by h igher-ranking individuals. T h erefo re, b o th types o f sounds seem to be a n integral p a rt o f the agonistic b eh av io r in clownfishes. G iven th a t they presen t som e differences in sound spectra a n d shape o f the tem p o ral envelope, it is im p o rta n t to em phasize th at these tw o types o f sounds w ould result from two different m echanism s. Aggressive sounds result from ja w teeth snapping [21,28] b u t the sound-producing m echanism o f submissive sounds is still unknow n. q l/i <u n £ .£ 3 re Z £ q Table 2. Summary (mean ± S.D.) of the seven acoustic features analyzed from submissive sounds produced by 9 Amphiprion frenatus. 1/1 O' à O' Im portance o f size-related acoustic signals for the group hierarchy q ■o ■o ui Interestingly, d o m in a n t frequency a n d pulse d u ra tio n o f submissive sounds display size-related v a riation in som e acoustic features. T h e m ore fish size increases, the m ore dom in an t frequency decreases, a n d the m o re pulse d u ra tio n increases. T h e sam e relationships have alread y b e en found for aggressive sounds am o n g 14 different species [21]. D ifferences in b o th sound characteristics w ere related to fish size a n d n o t to sexual status or social rank. H ow ever, size, sex a n d social ra n k are extrem ely related to each o th er due to the size-based h ierarch y w ithin each group [14,15]. In -4. percula , B uston a n d C a n t [29] dem o n strated th a t individuals ad jacen t in ra n k are separated by body size ratios w hose distribution is significantly different from the distribution expected u n d e r a null m odel: the grow th o f individuals is regulated such th a t each d o m in a n t ends up bein g ab o u t 1.26 tim es the size o f its im m ediate subordinate. T h e sam e k ind o f ratio (—1.30) is observed in the different groups o f A . frenatus o f this study (Fig. 4). T h e respect o f this ratio w ithin groups highlights th a t dom in an t frequency a n d pulse d u ra tio n can b e signals conveying inform a­ tion o n the social ra n k o f the em itter w ithin the group. Aggressive a n d submissive sounds are involved in interactions betw een group m em bers (Video S I, S2). Being associated w ith a specific display, they m ight have a different function w ithin the g roup. Indeed, aggressive sounds could possess a d eterren t function b y giving a re m in d er signal o f dom in an ce during interactions w hereas submissive sounds could possess a n appease­ m en t function by expressing the low er ra n k status du rin g interactions. Likewise, two different types o f sounds are em itted by the grey g u rn a rd Eutrigla gurnardus d ep en d in g on the in terac­ tions b etw een individuals: knocks are p ro d u c ed du rin g low levels o f aggression a n d grunts m ainly w hile p erfo rm in g frontal displays to opponents [30], C lear differences w ere found am o n g aggressive a n d submissive sounds a ttrib u te d to different individuals. All acoustic variables w ere significantly m ore variable b etw een th a n w ithin individuals a n d thus could all potentially provide cues to identify individuals. F u rth e rm o re , the m ost im p o rta n t variables to allow individual identification w ere d o m in a n t frequency a n d pulse d u ra tio n for b o th types o f sounds (Tables 4, 5). Pulse period, in a lesser extent, was also consistently im p o rta n t for discrim inating am o n g individ­ uals in the case o f submissive sounds (T able 5). In o rd e r to be good candidates for individual recognition, these acoustic features should p ro p ag ate th ro u g h the environm ent, a n d should be Q ui K .0 T3 II q i/i +i q £ vT p n0 S q i/i +1 <u 2 fC I"-. 3 t— c8 CU ro c 3 o 13 Q"rö ~o C .£ 3 <4- o O ■Ö > PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org 6 N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes A B ¡3 so°" >. g 700- <l> I Ö 600- eö o n 400- i -------------r 60 70 SL (mm) SL (nun) SL (mm) SL (nun) 16- 1514- -ö o u a 3 d. 1312- 1110- 9- 50- 240- 45_ a 220- c .2 T3 4° - ■ § 200- 'S w P- I 35‘ 'S 30- t» 2^- ’S G 3 180- (S) 160- SL (mm) SL (mm) c B sl 3.5- T3 C §« o q-H o X) E Z 3.0H □ A 2 .5 - ” T“ ” I“ ~~r~ ” T“ "T” 50 60 70 80 90 SL (mm) F ig u re 3 . In flu e n c e o f fish s iz e (SL) o n a c o u s tic f e a tu r e s o f s u b m is s iv e s o u n d s in A m p h ip rio n fre n a tu s. C o rre la tio n s o f (A) d o m in a n t fr e q u e n c y , (B) p u ls e d u ra tio n , (C) p u ls e p e rio d , (D) n u m b e r o f p u ls e s p e r s o u n d , (E) s o u n d d u ra tio n , (F) s o u n d p e rio d a n d (G) n u m b e r o f s o u n d s p e r tra in a g a in s t SL. Fish ra n g e d fro m 4 4 to 112 m m in SL (N = 9). R esults a re e x p re s s e d a s m e a n v a lu e s o f all re c o rd e d p u ls e s fo r e a c h in dividual ( Ö = ra n k 4, □ = ra n k 3, A = ra n k 2). d o i:1 0 .1 3 7 1 /jo u rn a l.p o n e .0 0 4 9 1 7 9 .g 0 0 3 PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org 7 N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes Table 3. Compa ris o n o f th e a c o u s tic f e a tu re s o f s u b m is s iv e sounds betw een in d iv id u a ls o f t h e s a m e s o c ia r a n k b u t f r o m different groups o f A m p h ip rio n fre n a tu s . Acoustic variables Social ran k Dominant frequency (Hz) Pulse duration (ms) Pulse period (ms) Sound duration (ms) Sound period (ms) H p-value 2 108.4 <0.0001 3 42.11 <0.0001 4 49.54 <0.0001 2 79.16 <0.0001 3 37.72 <0.0001 4 139.0 <0.0001 2 121.5 <0.0001 3 35.13 <0.0001 4 64.19 <0.0001 2 6.418 0.0404 3 15.18 0.0005 4 10.27 0.0059 2 9.995 0.0068 3 22.80 <0.0001 4 12.31 0.0021 H values are th e result o f th e Kruskal-Wallis test (df= 2, n = 300). n, num ber of pulses analyzed. doi:10.1371 /journal.pone.0049179.t003 d etected by the receiver. S ound p ro p a g atio n in shallow w ater can result in signal d eg rad atio n over short distances, including sound pressure level a n d frequency atten u atio n , a n d sound d u ra tio n loss [31]. H ow ever, the effect o f e nvironm ental a tte n u atio n a n d signal d eg rad atio n should n o t im pose a m ajo r restriction w ithin a group o f clownfishes since all individuals in h ab it a restricted territo ry (the sea anem one) a n d spend m ost o f the tim e in close vicinity o f their host. Since d o m in a n t frequency a n d pulse d u ra tio n o f b o th aggressive a n d submissive sounds are size-dependent, tem poral a n d spectral inter-individual differences m ight be d etected b y m em bers w ithin the group. T eleost fishes such as Gobius niger (Gobiidae) a n d Sparus annularis (Sparidae) are able to discrim inate tonal sounds differing in frequency o f approxim ately 10%; the frequency discrim ination ability at 400 H z is a pproxim ately 40 H z [32]. In the clow nfish el. akallopisos, aggressive sounds em itted by non-breeders, m ales a n d females differ in d o m in a n t frequency by > 1 0 % [20], In A . frenatus, sounds em itted b y individuals o f different social ranks also differ in d o m in a n t frequencies b y > 1 0 % (T able 2). Such a n ability to discrim inate frequency differences has a lready b e e n observed in som e pom acentrids. In the dam selfish A budefduf saxatilis, fish size has a significant effect on aud ito ry sensitivity [33] : all fish are m ost sensitive to the low er frequencies (10CM-00 Hz) b u t the larger ones a re m ore likely to resp o n d to h igher frequencies (1000-1600 Hz). T h e effect o f fish size on h earin g abilities was also supposed in th ree different clow nfish species [34], A lthough the best h earin g sensitivity is a ro u n d 100 H z, small individuals w ere m ore sensitive to a larg er frequency interval (100-450 Hz), a n d thus they are m ore sensitive to the frequencies em itted by larg er conspecifics. N o in form ation related to fish size can be extracted from n u m b e r o f pulses p e r sound o r n u m b e r o f sounds p e r train. Differences in these acoustic features a p p e a r to be related to a difference in m otivation. M otivation is know n for playing a role in dam selfishes, reg ard in g th eir sounds p ro d u c ed d u rin g aggression. In Dascyllus albisella a n d D . flavicaudus , aggressive sounds are different a ccording to w h eth er they are em itted tow ards conspe­ cifics or heterospecifics, b ein g m ultiple-pulsed or single-pulsed, respectively [12,13]. In Pomacentrus partitus, the frequency o f sounds by a territorial resident is relatively low at the territorial b o rd er, b u t it rapidly increases as in tru d e r ap p ro ach es the residence [35]. In the clow nfish A . akallopisos, the m ost aggressive m ales w ere ch aracterized b y a h igher n u m b e r o f pulses p e r sound a n d a shorter pulse p e rio d (pers. obs.). T h e sm allest individuals (rank 4) in A . frenatus groups em itted the highest n u m b e r o f sounds p e r train (T able 2). All these variations in acoustic features m ight be related to the willingness to express the position w ithin the group hierarchy. F or exam ple, low er-ranking individuals m ight pro d u ce m ore submissive sounds in o rd e r to lim it aggressive acts from dom inants. No reproduction-related sound U nlike observations m ad e b y T a k e m u ra [22], no acoustical beh av io r was observed d u rin g reproductive activities in clow n­ fishes. M oreover, T ak e m u ra ’s d a ta are som ew hat doubtful sin c e -4. ocellaris, A . frenatus a n d -4. sandaracinos w ould em it sounds w ith high frequency co m p o n en t o f m ore th a n 2 k H z d u rin g rep ro d u ctio n [22]. A ccording to h earin g sensitivity in clownfishes (A. frenatus, A. ocellaris a n d -4. clarkii), the frequency range over w hich they can detect sounds is b etw een 75 a n d 1800 H z, a n d they are the m ost sensitive to frequencies below 200 H z [34], T herefore, this finding raises the question over the interest o f clownfishes to pro d u ce sounds they could n o t detect du rin g reproductive activities. It rem ains these sounds could ju st be a by-p ro d u ct o f the nest cleaning activities. In the field, clownfishes spaw n o n average from 1 .0 ± 0 .5 to 0 .6 ± 0 .1 tim es p e r m o n th d ep en d in g o n w h eth er they live in tropical w aters [16,36] or in m ore tem p erate regions [37,38,39]. In captivity, the spaw ning frequency is h igher a n d o n average 2 5 ± 5 .3 tim es p e r y ear [40,41], T his frequency was observed at Table 4. Means, ± S.D., range, within-individuals variability (C.V.W) and between-individuals variability (C.V.b) for th e four acoustic features analyzed from aggressive sounds produced by 14 Amphiprion akallopisos. Acoustic variables O verall M ean ± S.D. (ran ge) C.V.w (M ean) C .V .w (range) c.v.b C .V .b /C .V .w H* /> v a lu e Dominant frequency (Hz) 663 ± 199 (346-1207) 0.10 0.07-0.21 0.30 2.73 1577 <0.001 Pulse duration (ms) 13.4±3.9 (3.8-22.9) 0.10 0.06-0.18 0.29 2.90 1614 <0.001 Pulse period (ms) 75.9±13.4 (32.4-121.9) 0.15 0.09-0.21 0.23 1.53 203.9 <0.001 Number o f pulses per sound 3.9±2.2 (2-14) 0.50 0.30-0.68 0.56 1.12 25.55 0.0195 *Results of Kruskall-Wallis te st (df= 13, n = 1818) comparing differences betw een 14 individuals of A. akallopisos for each acoustic feature. Note th a t these values w ere calculated based on acoustic data obtained from Colleye e t al. (2009). n, num ber of pulses analyzed. doi:10.1371 /journal.pone.0049179.t004 PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes T a b l e 5. M eans, ± S.D., r a n g e, w ithin-individuals variability (C V .W) a n d be tw ee n -in d iv id u als variability (C.V.b) for t h e se v e n a c o u s tic fe a tu re s a nalyzed fr om su bm issiv e s o u n d s p r o d u c e d by 9 Am phiprion frenatus. G roup nu m b er A coustic variables Dominant frequency (Hz) Pulse duration (ms) Pulse period (ms) Number o f pulses per sound Sound duration (ms) Sound period (ms) O verall M ean ± S.D. (range) C.V.W (M ean) C.V.W (range) C .V .b C .V .b/ C .V .W 631 ±135 (431-1036) 0.10 0.09-0.15 0.21 1.90 213.7 < 0.001 593 ±139 (431-862) 0.10 0.08-0.12 0.22 2.20 251.0 < 0.001 552 ±105 (345-776) 0.09 0.08-0.11 0.19 239.9 < 0.001 7.4 ±2.1 (3.8-11.2) 0.10 0.09-0.11 0.28 2.80 232.4 < 0.001 >.5±2.8 (3.6-15.1) 0.10 0.09-0.11 0.34 3.40 250.Í < 0.001 9.1 ±2.8 (4.5-13.9) 0.08 0.06-0.12 0.31 3.87 233.2 < 0.001 10.7±2.0 (6.7-15.4) 0.10 0.08-0.12 0.19 1.90 143.Í < 0.001 11.9±2.5 (7.4-1 7.< 0.10 0.08-0.11 0.21 2.10 167.4 < 0.001 12.7±2.6 (8.2-18.4) 0.08 0.05-0.09 0.21 2.62 176.2 < 0.001 3.1 ±0.6 (2-5) 0.20 0.19-0.23 0.21 1.05 5.36 3.4±0.9 (2-6) 0.26 0.21-0.31 0.27 1.04 2.59 3.1 ±0.8 (2-5) 0.25 0.22-0.29 0.27 1.08 12.86 < 0.01 29.2 ±8.4 (9.8-48.2) 0.22 0.18-0.24 0.29 1.32 59.24 < 0.001 36.9 ±14.1 (16.6-72.4) 0.28 0.22-0.33 0.38 1.36 25.94 < 0.001 36.6 ±14.1 (15.0-73.8) 0.24 0.13-0.35 0.38 1.58 49.90 < 0.001 0.16-0.21 0.21 16.53 < 0.01 21.07 < 0.001 176.4±36.9 (92.2-295.3) Number o f sounds per train p -value 206.3 ±40.9 (135.6-280.9) 0.15 0 . 12 - 0.1 0.20 1.33 201.7 ±31.5 (118.3-266.3) 0.13 0.08-0.16 0.16 1.23 3.3 ±1.5 (2-9) 0.39 0.28-0.53 0.44 4.36 3.2 ±1.3 (2-7) 0.35 0.30-0.41 0.41 4.93 2.6±0.8 (2-5) 0.23 0.18-0.27 0.30 1.30 < 0.01 14.39 < 0.01 *Results o f Kruskal-Wallis te st (df=-2, n = 300) comparing differences betw een individuals in a group of A. frenatus for each acoustic feature, n, num ber of pulses analyzed. doi:10.1371 /journal.pone.0049179. t005 Oceanopolis A quarium with captive clownfishes for which spawning occurred approximately every two weeks. In this context, it could be argued th at the captivity modulates some aspects of the behavior [40] such as sound production during reproduction. However, 1) the pair o f A. clarkii reared a t Sesoko Station showed the same spawning frequency (~every 2 weeks), although its reproduction was restricted to sum mer season an d it was reared under semi-natural conditions (i.e. outdoor tank filled with running seawater and m aintained under natural photoperi­ od); 2) spawning was witnessed in the field for A. perideraion, and no sound was produced by the m ating pair during the reproductive event. Yet, recording of aggressive sounds during the same session supports the fact th at the recording material worked well. B A 120 - 110 - a o 100- 1.4- 90- o 80- c s 60- 50- 53 1. 2 - UO 40- 2 3 2 4 S o cia l rank 3 Group F ig u re 4 . Fish s iz e (SL) a n d s iz e r a tio s o f in d iv id u a ls a d ja c e n t in ran k w ith in e a c h g r o u p o f A m p h ip rio n fre n a tu s. A) T h e o b s e rv e d d is trib u tio n o f fish size (SL) w ith in e a c h g ro u p . B) D istrib u tio n o f b o d y size ra tio s b e tw e e n in d iv id u a ls a d ja c e n t in ra n k w ith in e a c h g ro u p . R esults a re e x p re s s e d a s m e a n ± S.D. v a lu e s ( □ = g r o u p 1, A = g r o u p 2, 0 = g r o u p 3). d o i:1 0 .1 3 7 1 /jo u rn a l.p o n e .0 0 4 9 1 7 9 .g 0 0 4 PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org 9 N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes O verall, sound p ro d u c tio n does n o t seem to be involved in the reproductive b ehavior o f clownfishes, w hich m ight be explained by som e p a rticu la r aspects related to their w ay o f life. T h e reproductive b eh av io r o f p o m acentrids is subdivided into the follow ing m ajo r categories [42,43]: 1) establishm ent o f territory, 2) selection o f nest site w ithin the territory, 3) p re p ara tio n o f the nest site, 4) courtship a n d p a ir form ation, 5) spaw ning a n d fertilization, a n d 6) p a ren tal care. Clownfishes conform to this general p a tte rn b u t are distinctive w ith regards to form ation o f p e rm a n e n t p a ir bonds th a t usually last for several years in m ost species [16,44], In o th er damselfishes, one m ale m ay m ate w ith several females du rin g a single spaw ning episode [42,44], In clownfishes, m ale does n o t n e ed to exhibit typical courtship b ehavior for a ttrac tin g fem ale. P air-b o n d in g is very strong a n d is co rrelated b y the small size o f th eir territories (centered on actinians) th a t is, in tu rn , correlated w ith the unusual social h ierarch y existing in each social group. O n the o th er h a n d , it seems th a t o th er cues such as visual signals m ig h t be useful for synchronizing reproductive activities. J u s t before spaw ning occurs, the fem ale joins the m ale a n d becom es m o re insistent in the nestcleaning activities, p ro b ab ly in o rd e r to convey visual cues ab o u t its readiness to spaw n. Likewise, it is possible th a t the m ale regulates its level o f nest-caring activity in response to visual stimuli received w hen inspecting eggs [16], A visual stim ulus o f this sort w ould signal the stage o f egg developm ent a n d the n e ed for increased fa nning a n d m o u th in g activities. Allen [16] ex p erim en ­ tally d e m o n stra ted th a t strong agitation o f the eggs is a requisite for hatching. H e also no ted th a t there was a p ro n o u n c ed increase in the a m o u n t o f m ale nest care on day six o f incubation. O n th a t day, the em bryos a re well developed w ith one o f the m ost noticeable features bein g the large eyes w ith their silvery pupils. Such a feature m ight serve as a n a p p ro p ria te visual cue. T h erefo re, o th er cues such as visual a n d p erh ap s chem ical signals m ig h t b e involved in reproductive activities. H ow ever, new behavioral tests w ould need to b e ru n to determ in e the p ro p e r role o f such signals d u rin g the rep ro d u ctio n o f clownfishes. restricted to agonistic interactions only, acoustic signals seem to be an integral p a rt o f their daily behaviors. T h e im plication o f acoustic signals in agonistic interactions m ay be a n interesting strategy w ith a n econom ic w ay for prev en tin g conflicts w hich otherw ise m ig h t escalate to a severe outcom e. C low nfish sounds c an b e divided into tw o m ain categories: aggressive sounds p ro d u c e in conjunction w ith th re a t postures (charge a n d chase), a n d submissive sounds always em it w hen subordinates exhibit h e ad shaking m ovem ents in reaction to aggressive displays b y dom inants. B oth types o f sounds show intraspecific differences related to fish size, highlighting th a t some acoustic features (i.e. d o m in a n t frequency a n d pulse duration) m ig h t be useful cues for individual recognition w ithin the group. T hese observations are o f significant im p o rtan ce because the social structure o f clownfishes strictly relies o n a size-based dom inance hierarchy. Supporting Inform ation Video SI Im plication o f aggressive sounds during agonistic interactions betw een group m em bers in the field. N ote th a t a fish is chasing a n o th e r one (smaller) while p ro d u c in g a series o f aggressive sounds. (AVI) Video S2 Behavioral posture (head shaking m ove­ m ents) exhibited by subordinates while producing subm issive sounds. N ote th a t fish m ake sounds while doing lateral quivering o f the b o d y th a t begins a t the head. (AVI) Acknowledgments T he authors would like to thank Prof. M asaru N akam ura (Sesoko Station, Tropical Biosphere R esearch C enter, University of the Ryukyus, Japan) and Dr. K enji Iwao (Akajima M arine Science L aboratory, AM SL, Japan) for helping to collect fishes and for providing hospitality and laboratory facilities. W e are also indebted R. Suwa, M. Alam, S. N akam ura, Y. Kojim a, Y. N akajim a, R. M urata, R. N ozu and N. Pandit (Sesoko Station, TBRC) for technical support. M any thanks to Dom inique Barthélém y (Oceanopolis, France) and Dr. Christian M ichel (Aquarium Dubuisson, Belgium) for providing free access to fishes during recordings. Conclusion U nlike o th er pom acentrids, sounds are n o t p ro d u c ed for m ate a ttrac tio n in clownfishes. It is likely a n evolutionary outcom e related to th eir peculiar w ay o f life: these fishes form small social groups including only one m atin g pair, in h ab it a restricted territo ry (the sea anem one), spend m ost o f the tim e in close vicinity o f th eir host a n d rarely in teract w ith o th er species o n the reef. O n the o th er h a n d , sounds seem to be im p o rta n t to reach a n d to defend the com petition for b reed in g status. A lthough they are Author Contributions Conceived an d designed the experim ents: EP O C . P erform ed the experim ents: O C . A nalyzed the data: O C . C ontributed reag en ts/ m aterials/analysis tools: EP. W rote the paper: O C EP. References 1. 2. 3. 4. S c h n e id e r H (1967) M o rp h o lo g y a n d p h y sio lo g y o f s o u n d -p ro d u c in g m e c h a ­ 9. n ism s in tele o st fishes. In : T a v o lg a W N , e d ito r. M a rin e B io -aco u stics, vol. 2. O x fo rd : P e r g a m o n Press, p p . 135—158. H a w k in s A D (1993) U n d e r w a te r s o u n d a n d fish b e h a v io u r. In : P itc h e r T J , e d ito r. B e h a v io u r o f tele o st fishes. L o n d o n : C h a p m a n a n d H a ii. p p . 129—169. 10. A m o rim M C P (2006) D iv e rsity o f s o u n d p r o d u c tio n in fish. In: L a d ic h F, C ollin SP, M ö lle r P , K a p o o r B G , e d ito rs. C o m m u n ic a tio n in fishes, vol. 1. E nfield: S la b b e k o o rn H , B o u to n N , O p z e e la n d IV , C o e rs A , C a te C T , e t al. (2010) A noisy sp rin g : th e im p a c t o f g lo b ally risin g u n d e rw a te r s o u n d levels o n fish. 11. 13. P a r m e n tie r E , K é v e r L , C a s a d e v a ll M , L e c c h in i D (2010) D iv e rsity a n d c o m p le x ity in th e a c o u stic b e h a v io u r o f Dascyllus flavicaudus (P o m a c e n trid ae ). M a r B iol 157: 2 3 1 7 -2 3 2 7 . 14. B u s to n P M (2003) S ize a n d g ro w th m o d ific a tio n in clow nfish. N a tu r e 424: 145— 15. 146. F ric k e H W (1979) M a tin g sy stem , re s o u rc e d e fe n se a n d sex c h a n g e in th e e d ito r. M a rin e B io-A co u stics, vol. 2. N e w Y o rk : P e rg a m o n Press, p p . 2 1 3 —231. C ra w f o r d J D , C o o k A P , H e b e rle in A S (1997) A c o u stic c o m m u n ic a tio n in a n e le c tric fish, Pollimyrus isidori (M o rm y rid a e). J C o m p P h y sio l A 159: 29 7 —310. L a d ic h F (1997) A g o n istic b e h a v io u r a n d sig n ifican ce o f s o u n d s in v o c a liz in g fish. M a r F re sh w B e h a v P h y sio l 29: 8 7 - 1 0 8 . 8. L ugli M , T o rric e lli P , P a v a n G , M a in a r d i D (1997) S o u n d p r o d u c tio n d u rin g c o u rts h ip a n d sp a w n in g a m o n g fre s h w a te r g o b iid s (Pisces, G o b iid ae ). M a r 7. a n e m o n e fis h Amphiprion akallopisos. Z T ie rp s y c h o l 50: 3 1 3 —326. 16. A llen G R (1972) T h e A n e m o n e fish e s : th e ir C la ssific a tio n a n d B iology. N e w J e rs e y : T F H P u b lic a tio n s In c ., N e p tu n e C ity . 28 8 p. F re sh w B e h a v P h y sio l 29: 1 0 9 -1 2 6 . PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org S c ien c e P u b lish ers, p p . 71—105. S a n to s M d , M o d e sto T , M a to s B J , G r o b e r M S , O liv e ira R F , e t al. (2000) S o u n d p r o d u c tio n b y th e lu sita n ia n to ad fish , Halobatrachus didactylus. B io aco u stics 10: 3 0 9 -3 2 1 . 12. M a n n D A , L o b e l PS (1998) A c o u stic b e h a v io r o f th e d a m se lfish Dascyllus albisella: b e h a v io ra l a n d g e o g ra p h ic v a ria tio n . E n v iro n B iol F ish 51: 4 2 1 —4-28. T r e n d s in E c o l a n d E v o l 25: 4 1 9 - 4 2 7 . T a v o lg a W N (1971) S o u n d p r o d u c tio n a n d d e te c tio n . In : H o a r W S , R a n d a ll D J, ed ito rs. F ish p h y sio lo g y , vol. 5. N e w Y o rk : A c a d e m ic Press, p p . 135—205. 5. W in n H E (1964) T h e b io lo g ic a l sig n ifican ce o f fish so u n d s. I n T a v o lg a W N , 6. B ro w n D H , M a r s h a ll J A (1978) R e p ro d u c tiv e b e h a v io u r o f t h e r a in b o w cichlid, Herotilapia multispinosa (Pisces, C ich lid ae). B e h a v io u r 67: 2 9 9 —322. 10 N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179 Sound Diversity in Clownfishes 17. 18. 19. 20. F ric k e H W (1974) Ö k o -e th o lo g ie d es m o n o g a m e n A n e m o n e fisch e s Amphiprion bicinctus (F re iw a s s e ru n te rs u c h u n g a u s d e m R o te n M eer). Z T ie rp s y c h o l 36: 4 2 9 — 30. 512. S c h n e id e r H (1964) B io a k u stisc h e U n te rs u c h u n g e n a n A n e m o n e n fis c h e n d e r G a ttu n g Amphiprion (Pisces). Z M o rp h O k o l T ie re 53: 4 5 3 —174. 31. C h e n K - C , M o k H - K (1988) S o u n d P r o d u c tio n in th e A n e m o n fish e s, Amphiprion clarkii a n d A . frenatus (P o m c e n trid a e ), in C a p tiv ity . J p n J Ic h th y o l 35: 9 0 —97. C o lle y e O , F re d e ric ii B, V a n d e w a lle P , C a s a d e v a ll M , P a r m e n tie r E (2009) 32. A g o n istic s o u n d s in th e s k u n k c lo w n fish Amphiprion akallopisos: s iz e -re late d 33. v a ria tio n in a c o u stic fea tu re s. J F ish B iol 75: 9 0 8 —91 6 . 21. C o lle y e O , V a n d e w a lle P, L a n te r b e c q D , E e c k h a u t I, L e c c h in i D , e t al. (2011) In te rsp e c ific v a ria tio n o f calls in clow nfishes: d e g re e o f sim ila rity in closely 22. 23. 34. re la te d species. B M C E v o l B iol 11: 365. T a k e m u r a A (1983) S tu d ies o n th e U n d e r w a te r S o u n d - V III. A c o u stic a l b e h a v io r o f clow nfish es (.Amphiprion spp.). B ull F a c F ish N a g a s a k i U n iv 54: 21—27. 35. 36. P a r m e n tie r E , L a g a rd è re J P , V a n d e w a lle P, F in e M L (2005) G e o g ra p h ic a l v a ria tio n in s o u n d p r o d u c tio n in th e a n e m o n e fis h Amphiprion akallopisos. 37. P ro c R Soc L o n d B 272: 1 6 9 7 -1 7 0 3 . 24. A k a m a ts u T , O k u m u r a T , N o v a rin i N , Y a n H Y (2002) E m p iric a l re fin e m e n ts a p p lic a b le to th e re c o r d in g o f fish s o u n d s in sm a ll tan k s. J A c o u s t S o c A m 112: 38. 3 0 7 3 -3 0 8 2 . 25. A m o rim M C P , V a sc o n c e lo s R O (2008) V a ria b ility in th e m a tin g calls o f th e L u s ita n ia n to a d f is h Halobatrachus didactylus: c u e s fo r p o te n tia l in d iv id u a l re c o g n itio n . J F ish B iol 73: 1 2 6 7 -1 2 8 3 . 39. 26. B ee M A , K o v ic h C E , B lackw ell K J , G e r h a r d t H C (2001) I n d iv id u a l v a ria tio n in a d v e rtis s e m e n t calls o f te rrito ria l m ale g re e n fro g s, Rana clamitans: im p lic a tio n s fo r in d iv id u a l re c o g n itio n . E th o lo g y 107: 64—84. 40. 27. C h ristie P J, M e n n ill D J, R a tcliffe L M (2004) C h ic k a d e e so n g s tru c tu re is in d iv id u a lly d istin ctiv e o v e r lo n g b r o a d c a s t d ista n c es. B e h a v io u r 141: 101—124. 41. 28. P a r m e n tie r E , C o lle y e O , F in e M L , F re d e ric ii B, V a n d e w a lle P , e t al. (2007) S o u n d P r o d u c tio n in th e C lo w n fish Amphiprion clarkii. S c ien c e 316: 1006. 42. 43. 29. B u s to n P M , C a n t M A (2006) A n e w p e rs p e c tiv e o n size h ie ra rc h ie s in n a tu re : 44. p a tte rn s , c a u se s a n d c o n s e q u e n c e s . O e c o lo g ia 149: 3 6 2 —372. PLOS ONE I w w w .plosone.org 11 A m o rim M C P , S tra to u d a k is Y , H a w k in s A D (2004) S o u n d p r o d u c d o n d u r in g c o m p e titiv e fe e d in g in th e g rey g u r n a r d , Eutrigla gurnardus (T rig lidae). J F ish Biol 65: 1 8 2 -1 9 4 . M a n n D A (2006) P r o p a g a tio n o f f is h so u n d s. In : L a d ic h F , C o llin S P, M ö lle r P, K a p o o r B G , e d ito rs. C o m m u n ic a tio n in F ish es, vol. 1. E nfie ld : S c ien c e P u b lish e rs, p p . 1 0 7 -1 2 0 . F a y R R (1988) H e a r in g in V e r te b r a te s , A P sy c h o p h y sic s D a ta b o o k . Illinois: H illF a y A ssociates. E g n e r SA , M a n n D A (2005) A u d ito ry sensitivity o f s e rg e a n t m a jo r d a m selfish A budefduf saxatilis fro m p o s t-s e td e m e n t ju v e n ile to a d u lt. M a r E c o l P ro g S er 285: 2 1 3 -2 2 2 . P a r m e n tie r E , C o lle y e O , M a n n D A (2009) H e a r in g a b ility in th re e clow nfish species. J E x p B iol 212: 2 0 2 3 -2 0 2 6 . R ig g io R (1981) A c o u stic a l c o rre la te s o f a g re ssio n in th e b ic o lo r d am selfish, Pomacentrus partitus. M .S c . T h e sis, U n iv e rsity o f M ia m i, M ia m i, FL. R o ss R M (1978) R e p ro d u c tiv e b e h a v io r o f th e a n e m o n e fis h Amphiprion melanopus o n G u a m . C o p e ia 1978: 1 0 3 -1 0 7 . M o y e r J T , Bell L J (1976) R e p ro d u c tiv e b e h a v io r o f th e a n e m o n e fis h Amphiprion clarkii a t M iy a k e -Jim a, J a p a n . J p n J Ic h th y o l 23: 23—32. O c h i H (1989) M a tin g b e h a v io r a n d sex c h a n g e o f th e a n e m o n e fis h , Amphiprion clarkii, in th e te m p e ra tu re w a te rs o f J a p a n . E n v B iol F ish 26: 2 5 7 —275. R ic h a rd s o n D L , H a r r is o n P L , H a r r io t t V J (1997) T im in g o f s p a w n in g a n d fe c u n d ity o f a tro p ic a l a n d su b tro p ic a l a n e m o n e fis h (P o m a c e n trid a e : Amphiprion) o n a h ig h la titu d e r e e f o n th e e a st c o a st o f A u stra lia . M a r E c o l P ro g S er 156: 1 7 5 -1 8 1 . G o r d o n A K , B o k A W (2001) F re q u e n c y a n d p e rio d ic ity o f sp a w n in g in th e c lo w n fish Amphiprion akallopisos u n d e r a q u a riu m c o n d itio n s. A q u a r iu m S cience a n d C o n s e rv a tio n 3: 30 7 —313. H o f f F H (1996) C o n d itio n in g , sp a w n in g a n d r e a r in g o f fish w ith e m p h a sis o n m a r in e clow nfish. D a d e C ity : A q u a c u ltu re C o n s u lta n ts, 2 12 p p . A llen G R (1991) D a m selfish es o f th e W o rld . M elle: M e rg u s P u b lish e rs. 271p. R e e se E S (1964) E th o lo g y a n d m a r in e zo o lo g y . O c e a n o g r M a r B iol A n n u R e s 2: 4 5 5 —488. F a u tin D G , A llen G R (1992) F ie ld g u id e to a n e m o n e fish e s a n d th e ir h o s t sea a n e m o n e s . P e rth : W e s te rn A u s tra lia n M u s e u m . 160 p. N ovem ber 2012 | Volum e 7 | Issue 11 | e49179