Prescribed Fire Lessons Learned Initial Impression Report Escape Prescribed Fire Reviews and

advertisement

Prescribed Fire Lessons Learned

Escape Prescribed Fire Reviews

and

Near Miss Incidents Initial Impression Report June 29, 2005 Prepared by Deirdre M. Dether Submitted to Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center

Summary of Escaped Prescribed Fire

Reviews and Near Miss Incidents What key lessons have been learned and what knowledge gaps exist? Introduction This analysis is the first known attempt to take a comprehensive look at escaped prescribed fire reviews and near misses. A total of 30 prescribed fire escape reviews and ‘near misses’ (see Appendix A and B) were analyzed to discover what, if any reoccurring lessons were being learned, or whether they were indicating emerging knowledge gaps or trends. It is estimated that Federal land management agencies complete between 4,000 and 5,000 prescribed fires annually. Approximately ninety­nine percent of those burns were ‘successful’ (in that they did not report escapes or near misses). This can be viewed as an excellent record, especially given the elements of risk and uncertainty associated with prescribed fire. However, that leaves 40 to 50 events annually we should learn from. This report is intended to assist in that effort. Evaluating formal reviews and After Action Reviews (AAR) can be a tool for burn personnel to expand their knowledge and supplement their own direct experiences. When reviews go beyond policy and accountability questions they can provide information that can add to our own direct experiences by broadening exposure to what can occur. Learning from other experiences may help avoid undesired outcomes. The intent of this report is not to point out ‘wrong decisions’, but rather it is to use all these individual ‘events’ to see if there are common themes and/or ‘weak signals’ occurring with these escapes and near miss events. The main focus of the analysis was to look for things prescribed fire practitioners could use as they prepare for future prescribed fires. Are there some factors that prescribed fire planners and/or burn bosses have been repeating in isolation? If so, what should be shared with others involved in the planning and execution of prescribed burns to continue to improve outcomes? Methods Three questions drove this inquiry: Can comparing these reviews allow us to glean important or emerging trends? Can these reviews help all agencies to learn? and Are we asking the right questions? Next, I posed three straight­forward questions: of the analysis addresses straightforward questions. Are there common reported ‘causes’ contributing to the escapes/near misses? Are there repeated findings and ‘lessons learned’ cited in the reviews? What are these? Lastly, I looked for potential emerging trends or patterns gleaned from collectively evaluating all the reviews. The trends or patterns may indicate a ‘blind spot’ that was not previously apparent without looking at all the reports together as opposed to an individual basis.

2

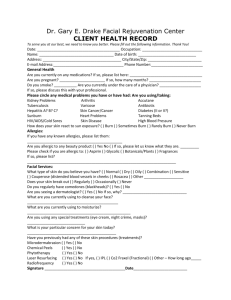

The Dataset Formal and information documentation from four federal land management agencies (FS, BLM, NPS and FWS) was evaluated in this assessment. Unlike the BLM, the FS did not appear to have a consistent formal review and documentation process. Both the FWS and NPS had too few samples collected to determine their questions and processes, even though current policies for these agencies provide a standardized process I reviewed 30 reports written for escapes or near­misses that occurred between 1996 and 2004. Only documents submitted to the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center (LLC), collected from agency websites by agency personnel, or located in personal ‘collections’ were used in this assessment (see Figure 1). It is unknown where and how many other reports may be available. This is an indicator that knowledge is not commonly retained and shared from these experiences so agencies have a greater likelihood of repeating ‘mistakes.’ Of these 30, most were formal escape prescribed fire reviews, several were draft review documents one was in a power point presentation, and two were After Action Reviews (AAR) of ‘near miss’ incidents. Most often the review was conducted at the request of an agency administrator following agency policy. The two ‘near misses’ were not declared escape prescribed fires, but the After Action Reviews provided valuable insights so were included in this analysis. Figure 1 Number of reviews by year used in this analysis from 1996 to 2004 Number of Reviews and Near Miss Incidents N = 30 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Escapes NOTE: It should not be construed that the years are problematic years since not all agencies systematically report escapes or near misses.

Near Miss Geographic area covered includes: several regions of the Forest Service including Northern Rockies (R1), Rocky Mountain (R2), Southwest (R3), Intermountain (R4), Pacific Southwest (R5), Southern (R8) and Alaska (R10). Reviews from Department of Interior agencies including BLM District and Field Offices; National Park Service units; and Fish and Wildlife Service were also used (see Figure 2). The states in alphabetical order (and number of reviews from each state) include Alaska (1), Arizona (5), California (3), Colorado (1), Florida (1), Idaho (2), Kansas (1), Montana (1), Nevada (1), New Mexico (3), Oregon (1), South Dakota (1), Utah (6) and Wyoming (3). Several vegetation­fuel complexes discussed in the reviews including: ponderosa pine, mixed conifer, and sub­ alpine fir, pinyon/juniper, chaparral, sagebrush/aspen, oak brush, grass, and activity fuels (slash). 1

The escapes or near miss incidents span from February to October. Most of the escapes were ignited in May (7) and June (5). Both near miss incidents occurred in September. Due to the many geographic areas represented in the sample it was not possible to evaluate any trends related to season. The amount of acres planned for ignition ranged from less than 5 acres up to several thousand acres for individual burn blocks. Several of the more recent escapes involved ignitions on multiple large­scale burn blocks. NOTE: It should not be construed any one agency has more or less escapes than another since escapes and near misses are systematically reported.

# Escapes/Near Misses Figure 2 Number of reports by agency used in this analysis. Incidents Reviewed by Agency 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 BLM FWS Escape NPS FS Near Miss NOTE: this analysis evaluated 30 total events, 28 of which were escapes over a nine­year period or an average of 3 per year (less than 8% of the estimated 40 to 50 escapes occurring annually on average). Of the 99% ‘successful’ burns we, as an ‘organization’ have no idea about the ‘near misses’ and ‘successful saves’ that have occurred. Many other escapes and near misses have occurred, but it is unknown how much formal or informal documentation exists from which we could gain experience. Of the thirty reports evaluated, several mentioned other escapes and near miss events, but only one report (one of the near misses) could be connected to another escape prescribed fire reviewed during this analysis. However, several escaped prescribed fire reviews involved multiple landscape­sized projects ignited either simultaneously or days apart, so they were covered in one review document. Background The concepts of a High Reliability Organization fit with the planning and execution of prescribed fire A High Reliability Organization (HRO) is one that experiences less than it’s fair share of incidents. Being and acting like a HRO should apply to organizations using prescribed fire to accomplish land management objectives. The use of fire is a high­risk business that operates in a highly variable environment yet needs to produce reliable outcomes. The excerpts provided below from Managing the Unexpected (Weick and Sutcliffe 2001) are here to set the context. This analysis is an initial attempt at applying the practices and principles and practices of how a HRO would evaluate escaped prescribed fires and near miss incidents. 2 All High Reliability Organizations Heed Close Calls and Near Misses

(from Keller October 2004)

High Reliability Organizations:

Regard close calls and near misses as a kind of failure that reveals potential

danger, rather than as evidence of the organization’s success and ability to

avoid danger. They pick up on these potential clues early on—before they

become bigger and more consequential.

Know that small things that go wrong are often early warning signals of

deepening trouble that provide insight into the health of the whole system.

Treat near misses and errors as information about the health of their

systems and try to learn from them.

Are preoccupied with all failures, especially the small ones.

Understand that if you catch problems before they grow bigger, you have

more possible ways to deal with them.

There are five practices of a HRO that can be grouped into two functional

categories (Weick and Sutcliffe 2001).

Mindful ‘Anticipation’ of the

Unexpected Mindful ‘Containment’ of the

Unexpected Preoccupation with Failure Reluctance to Simplify Sensitivity to Operations Commitment to Resilience Deference to Expertise Results

What questions are being asked in an escape review ? Since reports were often generated to meet agency direction the questions mostly focused on policy and accountability issues. The most common questions were: A. Is agency policy, guidance and/or direction adequate? Was is followed? Initial observation – Most of the reviews determined that good or sound policy and guidance existed. However, when review teams looked at whether policy was followed, the answer was not always a yes. In a few cases, review teams also compared the local level direction relative to national direction. In at least four cases the finding was the same. The local direction was not consistent or was outdated relative to existing national direction at the time of the escape.

3

B. Was the burn plan prepared and executed relative to agency policy? Was it a ‘good’ plan? Initial observation – Few reviews concluded that burn plans did not meet policy. However most listed several weaknesses or noted parts missing in burn plans. Common areas cited as weak within the burn plans included complexity and risk assessments, and thoroughness of the ignition, holding and contingency plans. Another reoccurring issue was the lack of fire behavior calculations. Sometimes the fuel model did not accurately represent the fuels and potential fire behavior of the burn area. The fuel model selected generally under­predicted potential fire behavior. Another reoccurring problem was that all the fuel types within the burn area were not evaluated and incorporated into the burn plan. Some of the reviews also noted that burn personnel failed at times to follow what was in the burn plan. This includes obtaining spot weather forecasts or monitoring weather and other prescription parameters for the timeframes specified prior to ignition. Not all procedures were followed during execution. Reviews noted that required documentation was often poor or lacking. C. Was the planning and execution of the prescribed burn done by qualified personnel? Initial observation –In only two of the reviews were questions concerning the qualifications of burn personnel an issue. In one case the burn boss was from another agency so the reviewing agency was uncertain if the individual was qualified and needed to verify qualification documentation with the other agency. In the other case, the question was whether proper certification procedures were followed. However, several of the reviews noted that burn bosses, while ‘qualified’, were often ‘inexperienced’ with the fuel type(s), which contributed to the escape of the prescribed burn. In addition, I noticed a trend towards including questions beyond policy, accountability and qualifications. Such reviews are moving toward ‘lessons learned’ and what needs to be improved and applied to future projects. Two reports included in this analysis did not involve an escaped prescribed fire, but shared near misses which indicates a movement beyond focusing on accountability. Other Observations Other questions raised were developed based on issues that were specific to that particular event. However, it was interesting to note there were some common themes among those areas evaluated by review teams. At least 10 of the 28 escaped fires burned onto private ground. Therefore, one area added on often looked at how well collaboration, communication and coordination occurred with the public and between cooperating agencies. Not all reviews evaluated the linkage of the environmental document to the burn plan. Often when this was done there were missing mitigations from the NEPA document that were not incorporated into the burn plan. All stopped at the point of looking at actions beyond the escape although most noted that there was safe and successful transition from the prescribed fire to suppression actions.

6 Agencies are not yet fully behaving as a learning organization ­­ escapes

and near misses are not systematically and routinely reported, evaluated,

and shared.

What are the Common ‘Surprises’?

The ‘surprises’ came in three areas – Fuels and Fire Behavior, Weather and

Communication and Coordination. Many prescribed fire practitioners have already experienced one or more of these types of ‘surprises’ possibly all on the same prescribed burn whether the burn escaped or not. Several of the prescribed fire reviews and near misses expressed ‘surprise’ about the fire behavior they saw from the various vegetation­ fuel complexes. In some cases, the personnel involved with the burn knew to expect something different than what models predicted, but the fire behavior (either rate of spread and/or flame lengths) was not even imaginable. A re­occurring theme mentioned by the reviews was that many escapes occurred because conditions were not ‘normal’ (e.g. periods of drought, warmer and drier than normal). When burns were implemented, burn personnel ‘failed to adjust operational procedures’ to account for the ‘abnormal’ conditions. Since surprises, expectations and the ability to manage the unexpected are linked together; therefore it is important to focus on what surprised burn personnel, and why. In Managing the Unexpected Weick and Sutcliffe (2001) state that ‘surprises’ come in many different varieties. Prescribed burn personnel have experienced many of the ‘varieties of surprise’ listed below. Weick and Sutcliffe describe what can occur if we blindly follow expectations and do not update them with new information. “The continuing search for confirming evidence postpones the realization that something unexpected is developing. If you are slow to realize that things are not the way you expected them to be, the problem worsens and becomes harder to solve. When it finally becomes clear that your expectation is wrong, there may be few options left to resolve the problem.”

Varieties of Surprise

1st Form – Something appears which you had no expectation, no prior model

of the event, no hint that it was coming.

2nd Form – The issue is recognized, but the direction of the expectation is

wrong.

3rd Form – Occurs when you know what will happen, when it will happen, and

in what order, but you discover the timing is off.

4th Form – Occurs when the expected duration of the event proves to be

wrong.

5th Form – Occur when the problem is expected, but the amplitude is not.

see Chapter 2 pages 35­39

7

Surprises in Fuels and Fire Behavior ­ In numerous reviews, the rate of spread, flame length and resulting spotting caused much of the challenge for burn personnel. Fuels are often the source of unexpected or overlooked sources of trouble. One burn boss related this example of unexpected fire behavior in a fuel type involving standing dead pinyon­ juniper: the trees had been bug­killed with no needles left on the crown yet during burn operations the fire was able to move into the crowns of the standing dead trees and sustain fire spread through the aerial fuels much like a typical crown fire. In this case, an adequate control line stopped the spread of fire so the prescribed fire did not escape. Another example of unexpected fire behavior came from a small pocket of fuels adjacent to the burn area boundary. The small pocket of fuels was not the dominant fuel type within the burn area and was not noted in the burn plan as a potential source of heat and spotting. Another reoccurring ‘surprise’, reported in several escapes was greater than ‘normal’ fuel loading due to seasonal variation (greater moisture increased fine fuels) or a change in land management activities (area rested from grazing for 2 years prior to the burn actually being implemented). The change of conditions was not captured or discussed in the burn plan nor noted prior to ignition which would have caused a plan to be re­evaluated for complexity, risk and/or adequacy of contingency plans.

What are we not ‘seeing clearly’? Are we not appreciating how complex

burns are?

The use of natural barriers – change in fuel or vegetation type, moisture gradient either by changing topography or nighttime recovery often failed to check the spread of fire or put the fire out. In several cases changes in fuel or vegetation types were planned to check the spread of fire. In one case, aspen stands were to be used as a natural barrier to fire spread, but the aspen did not check spread as expected because the burn was not implemented during the planned season. In another case, a ‘swamp’ adjacent to the burn area was planned as a natural barrier. However, when the burn was implemented conditions had changed (i.e. the swamp was dry) and this area did not contain the spread. Prior to ignition burn personnel did not check whether this area would stop the spread of fire. With several prescribed burns, nighttime humidity recovery was expected to stop or check the spread of fire. In each case, burn personnel did not gather on­site information to confirm whether the area did experience sufficient humidity recovery. The review teams recommended that prescribed burns relying on this technique should staff the area through the night and monitor on­site conditions. Surprises in Weather – Surprises in weather often combined with or caused other surprises to occur. A number of reviews stated that ‘drought’ conditions were believed to be a contributing factor. In several cases changes in moisture (increased precipitation) changed the amount of fine fuels present at the time of the burn which was not accounted for in the burn plan. Unexpected winds (strength, duration, etc) were very common contributing factor to many escapes. Proximity of thunderstorms to burns may be another emerging knowledge gap or indicates a gap in ‘sense­making’. Burns that reported strong, erratic winds resulting from thunderstorm development nearby were ‘surprised’ by the effect. One case related that the storm was forecasted, they could see the cells developing miles away from the burn area, but felt that since the storm was approximately 30 miles away, they would be ‘ok”’ and proceeded with ignition. Another prescribed burn escaped due to the effects of a

8

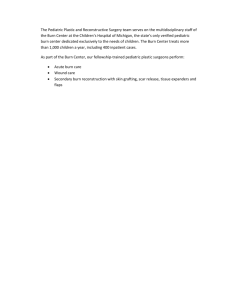

nearby thunderstorm. The weather forecast did predict the development of thunderstorm activity, but burn personnel did not recognize the potential impact to the prescribed burn. Surprises in Communication and Coordination – This was a common theme among the largest and most notable escapes (Lowden, Cerro Grande, Sanford, Cascade II and North Shore Kenai Lake). Other reviews noted concerns when burning adjacent to non­ agency lands. Two re­occurring themes were lack of proper notification and recommendations for developing agreements with adjacent landowners. Problems with lack of proper notification occurred prior to burning and/or timely notification once the prescribed burn had escaped burn boundaries. Proper notification of the individuals or agencies affected by an escape was often delayed because they did not know whom to contact. Developing relationships and contacts well before ignition followed by notification just prior to burning was a common recommendation. In cases where the prescribed burn escaped onto private ground an agreement with the landowner prior to the burn would have eliminated the need for declaring an escape. The lack of coordination and communication among key burn personnel and assisting/cooperating agencies or units also appeared to be a re­occurring theme in several escapes. What are the Common ‘Surprises’? Two patterns were observed and explored in this analysis. The first pattern was the tendency to underrate overall prescribed fire complexity using the NWCG complexity rating system. A second pattern emerged when chronologies of escaped prescribed burns were examined and evaluated for common causal factors. Although not all reports mentioned the overall complexity rating, most did indicate there were problems with how individual elements of the complexity rating system were addressed (e.g., underrated, missing rationale or reasons a particular rating was selected, or was inconsistent with the agency’s policy). This avenue was not explored further to determine if there were elements consistently underrated. Complexity ­ All agencies evaluated currently use the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) complexity rating system (NWCG January 2004 NFES 2474). The complexity rating system consists of 14 elements to evaluate and determine risk, potential consequences and technical difficulty. The rating system is relatively comprehensive, and is designed to aid in selecting the correct level of difficulty. An initial rating is recommended during project planning and development followed by a final rating, which is done during burn plan development. The overall complexity rating was not systematically reported as part of the escaped prescribed fire review process. Half of the burns did not have the overall complexity rating reported although several within this group did note that elements of the complexity rating within the burn plan needed improvements (e.g. rationale for rating missing and if rated ‘high’ mitigations were not included in the burn plan per policy). There was a fairly even distribution between Low, Moderate and High complexity of those that did report the overall complexity rating of the burn (Figure 3). Review teams concluded that many burn plans with an overall rating of Low or Moderate were ‘underrated’ in complexity. That is, they were actually High complexity instead of Low or Moderate (see Figure 3). In several cases, one noted cause for underrating complexity was due to the preparer not following agency direction. A separate theme occurred when individual burns were rated Low to Moderate but then were implemented at the same time. Review teams noted burns conducted simultaneously would not warrant the same overall rating as the individual burn. In other words, two Low complexity burns implemented at the same time did not necessarily still rate a Low. Also noted in these cases was that burn personnel should have considered

9 changing the level of management oversight when conducting burns simultaneously (i.e. burn boss level switching from a RxB3 to and RxB2). However, the NWCG system specifically states that the “rating system is for a single prescribed fire project”. Figure 3 A comparison of overall complexity ratings for all projects reviewed. One column shows the complexity rating as determine during burn plan development versus the complexity rating determined during the review process. Overall Complexity Rating # of Escapes/Near Misses Escapes and Near Misses n=30 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Low Moderate As Planned High Not Reported Determined After Chronologies – There were two distinct groups in terms of the length of time from test burn to escape declaration. Prescribed burns either escaped very quickly or escapes occurred several days after the main ignition period while in the patrol and monitoring phase. The chronologies of at least 12 of the 28 escapes indicate that from the time of the ‘test burn’ or ignition it took 6 hours or less before they were declared an escape or should have been declared an escape (see Tables 1­3). Several more occurred before the ignition phase was complete. Weather changes (winds increased and/or shifted direction and relative humidity dropped over short timeframes) were associated with these events, leading to spotting. However, there are other factors often associated with these events. Many reviews indicated the fire behavior was more than expected or anticipated and burn personnel did not fully realize what kind of fire behavior to expect. Also, the fuel complex either inside or outside the planned boundary caused unexpected fire behavior that was often not addressed in the burn plan. Another connected reason for burn personnel being mislead about what kind of fire behavior to expect was the incorrect selection of fuel model(s) during burn plan development. Fuels models selected for burn plan development often underrepresented fire behavior. Another factor mentioned several times was lighting at the upper end of the prescription which caused prescription parameters to be exceeded often during the peak of the day. However, it was not always a ‘surprise’ to burn personnel that the prescription parameters would be exceeded during the ignition period. Sometimes burn personnel would start earlier in the morning in an attempt to compensate for the expected trend in conditions. However, either the conditions occurred sooner than expected or delays in implementation caused the ignition phase to be ongoing when the conditions exceeded the prescription parameters. Burns were sometimes lit outside of prescription parameters. A final factor was the test fire was not conducted in a representative location. Test fires were conducted in locations that were in cooler or moister locations or conducted in fuels

10 with a different kind of fire behavior than the burn area. At the selected locations fire behavior was lower (lower flame lengths or rate of spread) misleading burn personnel. Commonalities of prescribed fires that were declared an escape the day of

ignition The vegetation­fuel complex played the biggest role as the immediate causal factor in escapes. Several of the escapes noted that increases in fine fuel loading due to seasonal variation ‘surprised’ them. Burn plans were prepared assuming ‘normal’ fuel loading so during execution burn personnel may not have accounted for this influence. One burn boss did note the changed conditions and made some adjustments to holding forces to compensate. However, other factors including not fully appreciating the influences of the fuel type still resulted in an escape. In several cases, the escape occurred during the ‘test fire’ phase. Another noted factor was that spotting occurred early and/or frequently during ignition phase, and in some cases during the test fire or black­lining phase. Spotting, according to some burn bosses, is a common occurrence with prescribed burning.

“A thorough recon of the area surrounding a burn unit is invaluable. Think

about the worst case scenario, and then imagine the worst case going bad,

then go back and plan your contingency”.

Lesson learned from an escape fire review

Commonalities of prescribed fires declared an escape during the patrol and

monitoring phase Weather was commonly reported to have gotten progressively warmer and drier prior to escape. The reviews often cited that the weather was known to be ‘more than normal’ for the time of year. Increased winds or a wind ‘event’ that increased wind speeds for a short period of time contributed to the burn being pushed outside of the allowable burn area. In most cases, the burns were patrolled on a daily basis. In burns of longer duration the patrols noted activity increasing in the burn unit (smokes or open flaming of fuels). In some cases the patrols noted ‘smokes’, but thought they would not threaten boundaries. In some cases, personnel knew other prescribed burns had recently escaped within their geographical area. However, in spite of these ‘signals’ there were no changes in actions such as altering mopup protocols or utilizing heat detecting equipment, etc. In some cases, not having someone directly assigned as the lead for a prescribed fire until declared out caused lapses in awareness of the situation and direction to change procedures. One review provided six useful signals that may indicate conditions are not normal and suggest changes to operational procedures. 1) No significant precipitation in nearly two months. 2) Receiving severity funding just prior to igniting a burn. 3) Fire restrictions have just been lifted for your area. 4) Thousand hour fuels are at or below critical levels (or other levels that indicate they are available to burn) 5) There is a pattern of below normal moisture (precipitation) for more than one year. 6) Trends for dead and live fuel moisture are they at or below long­term averages.

11 Go/No Go ­ It is easier to light a burn than not to light one.

It is easy to let the ‘pressure to produce’ override the signals (ignore them or

don’t look for them) indicating that a burn may not be best executed that day

or even that year.

Other Observations of Repeated Lessons Learned and Recommendations. Many escapes began to take place well before the first spot or slopover. A repeated recommendation for future prescribed burns started with project design and the environmental assessment. Burn block boundaries that were not developed based on known fire behavior characteristics were often a contributing factor in the escape. In some cases, resource specialists selected areas without input for logical or realistic control points. This limits options to successfully implement a prescribed burn or delayed a burn because changes needed to be analyzed and disclosed in an environmental document. Having expertise in fire behavior and practical experience with prescribed fire will help resource specialists to develop ‘logical’ burn blocks. Review teams often cited one key weakness with overall burn plan development. The weakness noted was burn plans for complex burns that did not have sufficient depth and detail to match the complexity of burn. Large­scale burns will likely have multiple aspects, variable vegetation­fuel complexes, resource objectives and constraints that require more complex planning and burn organization to implement successfully. Conclusions and Recommendations The disparate types of information across the agencies made an assessment of this nature challenging, particularly tracking potential knowledge gaps or identifying developing trends, and especially without being able to access all existing reports. Despite this, the collected data do converge on several important lessons that we as a fire community need to learn. These are outlined below. Reviews of all escapes and near misses should be consistently conducted, collected and stored in a centralized location to assist the community in learning from its experiences. A consistent framework with common questions and documentation would help make future lessons learned efforts more meaningful and samples more robust. While individual reviews provide opportunities for the local unit to learn, consistency would better assist this learning across Agencies. Such a consistent interagency framework to conduct reviews of escapes and near misses could assist all practitioners and agency administrators to identify knowledge gaps. As Weick and Sutcliffe (2001) recommend, sharing of near misses may tell us more about reliability than escapes, but they also provide us the opportunity to ensure that we take signals as a sign that things are ‘ok’ or ‘not ok’ until proven otherwise The NWCG Complexity Rating System Guide should be explored to look at how to handle cases where burns are simultaneously lit potentially changing complexity, management oversight and organization structures. Is it true we underrate complexity? If so, why and in what context? Is there a tendency to underrate overall complexity or individual elements – risks, potential consequences and/or technical difficulty ­­ because experience with particular situations is low so it is not recognized as a potential source of problems?

12

Is there a tendency to underrate because adequate resources and skill levels are not available to the unit (e.g. a hesitancy to identify a burn as more complex because an RxB2 or RxB1 is not on the unit or readily available). There maybe a gap between the intended use of the complexity rating system and policy. Per policy, a final complexity rating is to be done and included in the signed burn plan. This freezes the rating for implementation. There is no mechanism or direction to aid burn personnel to reevaluate overall complexity or trigger the need to increase the level of detail in burn plans when multiple plans are implemented at the same time. Vacancies in key positions were noted in several reviews as having an important impact on fire operations. The recommendation in the reviews was to fill vacant positions to help relieve the stretched workforce experiencing expanding programs. We continue to be surprised by fuels and fire behavior. Why? Have we lost our knowledge base and skills in identifying the carrier of fuels and selecting the most appropriate fuel model? Or, are we dealing with vegetation­fuel types that are more complex or different than we have experiences with or fuels models to represent? Likely, both of these issues are causes as well as others. Due to limitations of the models to reflect reality practitioners may be reluctant to use these tools. Even with the limitations of fuel models and fire behavior modeling these tools assist with identifying sources of problems. However, continued training in usefulness and shortcomings of fuel and fire behavior models may help prescribed fire planners. Other specific recommendations include:

·

Continue to share lessons learned with other fire management personnel to broaden experiences levels.

·

Investigate mechanisms to minimize possibility of escape the day of ignition. For instance, checking fuel receptivity outside the unit may be as important as how it burns inside the perimeter. Test all fuel types. If there is more than one fuel inside or outside the planned boundary we should be aware how each of these are going to respond. Holding and contingency forces then can be ramped up or down accordingly.

·

Monitor leadership assignments and personnel transitions closely to ensure someone is directly assigned as the lead for a prescribed fire until the fire is declared out. Next Steps to Become a HRO Achieving and maintaining high reliability requires not just intellectual understanding, but translation of this into practice. This review of reviews has not revealed any earth­ shattering weaknesses; all weaknesses summarized above have been known previously. What it has done is to further highlight several trends and points of weakness in our practice. How do we move forward from here? This section is included in the hopes that it will stimulate further discussion…and actual change in our practice. ‘Reviews’ need to be approached as a tool for learning and be clearly separated from disciplinary actions. Did you have a good plan? Did you follow the plan? Did you execute it with qualified people? These are all good accountability questions. However,

13 accountability and learning from undesired outcomes are often at odds with each other. Accountability can lead down a path of blame after which opportunities for learning disappear. If fire use practitioners are going to move toward becoming a learning organization then we have to examine our ‘failures’ as an HRO. Reviews for learning should use questions that help evaluate expectations, assumptions, surprises and blindspots. Further develop and integrate efforts exploring how to become a learning organization and operate consciously use the principles of a High Reliability Organization. Efforts so far include conducting After Action Reviews and Managing the Unexpected workshops. Both of these have been useful pathways to explore and should be developed to further integrate these concepts into daily practice. Agencies need to further explore/validate the emerging trends such as a tendency to ‘underrate’ complexity, look at why this is happening and what we need to overcome that tendency. Another area that may need further work is to look at why some vegetation­fuel complexes seem to repeatedly ‘surprise’ practitioners especially the more flammable fuels like cheatgrass and pinyon­juniper. Another area that seems to be a struggle is for practitioners to recognize risks and develop burn plans for complex landscape scale burns. One way to overcome this tendency is to encourage burn plan development by a team (prescribed fire planner, burn boss, holding and ignition specialists) because more eyes, and more experiences will be added to the preparation of the plan. How can we avoid being blinded by burn plans (Weick and Sutcliffe 2001)? Federal land management policy requires burn plans. How can we strengthen their use? One option might include drawing on concepts from Managing the Unexpected,. A team could explore ways to overcome the trap of expectations and tendencies to seek confirming evidence. For example, increasing awareness through NWCG courses that burn plans could blind us (how and why does that happen?). Another possibility to consider are ways to develop burn plans with a balanced approach ­­ focus on what we do not want to have happen as much as we focus on what we do want to have happen. It could be stressed to prescribed fire planners they should focus on ways to look for ‘disconfirming’ evidence that they are not in prescription and put them in the monitoring plan. Since it is the policy of federal land management agencies that burn plans are required this area would warrant further exploration. Agencies should look into ways to build line officer and agency administrator ‘sensitivity to operations.’ Only two of the most recent reviews explored and acknowledged the role of the agency administrator. One case commented on the active role of the agency administrator, but also noted they had not yet attended a mandatory training (i.e. Fire Management Leadership). The other case praised and acknowledged the active role of the agency administrator who was on­site while the burn was being conducted and played a keyed role once the prescribed fire had been declared an escape. Agency administrators will play a key role in operating as a HRO. Acknowledgements Intermountain Region (R4) FAM, particularly Dave Thomas, Regional Fuels Specialist for promoting learning organization, supporting and funding a detail program analyst to the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center to develop this analysis.

14 Tim Sexton, National Fire Use Specialist, Forest Service and Al Carrier, National Fuels Management Specialist­Operations, Bureau of Land Management for digging into their files and supplying additional escape prescribed fire reviews not electronically available. This report is intended to further the mission of the Wildland Fire Lesson Learned Center: Collect and analyze observations Share lessons learned and best practices, and Archive knowledge and information.

15 References and Citations Garvin, David A. 2000. Learning in Action: a guide to putting the learning organization to work. Harvard Business School Press. 256 pages. Keller, Paul. October 2004. Managing the Unexpected in Prescribed Fire and Fire Use Operations – a workshop on the high reliability organization. RMRS­GTR­137. 73 pages. National Wildfire Coordinating Group. 2004. Prescribed Fire Complexity Rating System Guide. NWCG NFES 2474. 45 pages. Snook, Scott A. 2000. Friendly Fire: the accidental shootdown of U.S. Black Hawks over Northern Iraq. Princeton University Press. 257 pages. Weick, Karl E, and Kathleen Sutcliffe. 2001. Managing the Unexpected – assuring high performance in an age of complexity. 200 pages.

16

Table 1 Timeline of Escaped Prescribed Burns Involving Fine Fuels (Grass and Grass-like) Vegetation-Fuel Complexes. In three out of five escapes, the fine fuels were

not the targeted vegetation for burning.

Burn

Date

Fuel

Time

0800

0900

1000

1100

1200

1300

1400

1500

1600

1700

Blacklining at upper end of prescription window. Plan written for normal conditions, but conducted with “abnormal” level of fully cured

cheatgrass. Burn boss limited experience with fuel type.

During

initial

blacklining

Pa-CA

June 22,

1998

Cheatgrass

No chronology provided

Two spots occurred “shortly after ignition. First spot contained. Second spot grew to 4 acres and prescribed burn declared an escape.

Holding actions limited due mechanical failure of helicopter.

BQ-CA

July 1, 1998

Heavier

loading

cured grass

“shortly

after

ignition”

1235 test ignition Declared ?

Had no lookouts posted to look for spots. While more than the minimum holding forces were on-scene unable to respond quickly to

slopover due to hindered access. Burn boss limited experience with fuel type.

Me-UT

Sept 9, 2004

Cheatgrass

During

“test

“burn”

1545. 1602 1625

IL-AZ

February 4,

2004

Reed Grass

Main ignition of unit began 15 minutes after test burn. Ignition stopped after 50 minutes. Possible spot across river was reported and

confirmed in 5 minutes. Holding forces were unable to locate and control spot immediately due to thick smoke and access was also

hindered.

Less than 2

hours

0945..1000…1050 1110 1115

Prepared by D.Dether

June 2005

1

Table 1 (cont) Timeline of Escaped Prescribed Burns Involving Fine Fuels (Grass and Grass-like) Vegetation-Fuel Complexes.

Burn

Date

Fuel Type

Time

LR-CA

July 2, 1999

Invasive

weeds

Less than 3

hours

0800

0900

1000

1100

1050

Prepared by D.Dether

June 2005

1200

1200

1300

1400

1500

1600

1700

1300-20..1330

2

Table 2 Timelines for Escaped Prescribed Burns Involving Shrubland/Woodland Vegetation-Fuel Complexes.

Burn

Date

Fuel Type

Time

Bl-WY

June 4, 2003

Pinyon/

Juniper

3 hours

0800

0900

1000

1100

1200

1200

1300

1400

1500

1600

1700

1245- 1300..1345………………1500

Main ignition of one area began 10 minutes after test burn. Approximately 1 hour later, ignition began in a second area away from the

first. Multiple spots occurred some with rapid rates of spread. Test burn was not conducted in representative location.

Ca-UT

Sept 23,

2003

Heavy, oak

brush

5 hours

1230 1240

1320

1430

1515

1630

1700

Prescribed burn not declared an escape when it should have been.

SC—

April 10,

2003

Decadent

bitterbrush

& P/J

IB-FL

March 2,

2004

Southern

Rough &

swamp

5 hours

1130 1200

1400

1640

Not declared an escape unit 5 days after ignition, but review determined the prescribed fire should have been declared within 3 hours of

ignition due to fire behavior being outside of prescription parameters. No documentation of test burn.

Less than 3

hours

Prepared by D.Dether

June 2005

Est. 1100

1400

3

Table 3 Timeline of Escaped Prescribed in Forested and Slash Vegetation-Fuel Complexes. While most escapes in these vegetation-fuel complexes occurred days after

ignition during the patrol and monitoring phase; however, several did occur during the ignition phase with two declared an escaped prescribed fire within six hours.

Burn

Date

Fuel Type

Time

0800

0900

1000

1100

1200

1300

1400

1500

1600

1700

No mention of when test fire was conducted but lit in an area not representative of fuel conditions. Initial spot fires handled by holding

forces.

Pi-NM

March 12,

1996

Ponderosa

pine, mixed

conifer &

P/J

Less than 2

hours

NR-UT

June 28,

2001

Slash w/

subalpine fir

Less than 5

hours

LJ-AZ

May 5, 2004

Ponderosa

pine & P/J

Same day

as ignition.

Unknown

start time.

1130

1230 1300 “shortly after 1300”

1300

Unknown

1100

1143

1400

1500

1600

1645

1736

1517

Ignition was planned for and stressed during briefing the need to be completed by 0900 hours due to observed burning conditions. Ignition

was not completed within timeframes due to logistical and mechanical problems.

Prepared by D.Dether

June 2005

4

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Lizzie Springs

Pinatosa

Banner Queen

Yr

Agency

1996 BLM

Unit

Rock Springs

District

1996 FS-R3

Mountain Air

RD, Cibola NF

1998 BLM

El Centro

Resource

Area, California

Desert District

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

State

Planned Acres

WY

Not Reported

(NR)

NM

Total 9,000 in

project, approx.

5,100 ac actually

burned w/in

planned area

CA

650

Escape Size and

Consequences

Complexity

Rating

350, unknown if

these acres were Not Reported

outside unit or total (NR)

ac burned

2,000 acres

unplanned

including 300 ac

pvt

NR

High - aerial &

hand

Appendix A

Veg/Fuel Complex

Conifer including

heavy subalpine fir

timber with aspen.

Not Reported

More fine fuel due to (NR)

2 yr rest from

grazing.

Multiple - ponderosa FM 9 & 10.

pine, mixed con & Used FM 10 for

P/J, oak shrub

BEHAVE runs.

Mature chaparral

(chamise) w/ unusual

amount of grass due

to unusual amt of ppt

with el Nino.

NR

1

FBO Fuel

Model &

Modeling

Season of Ig

(mo/day)

Oct 2-4

12-Mar

Used brush

model, but did

not account for

1-Jul

amt of grass

and dead/live

ratio in brush

Length of time from Test Fire or Ig

to being declared an Escape

8 days

1.5 hours No mention of test fire.

Hand ignition began ~1130 hrs. Spot

fires noticed between 1230-1300 by

hand ignition crew, but able to control

with holding resources. RxB fired main

ridge inside unit with PSD; however fire

spread downhill rapidly towards

perimeter. Shortly after 1300 declared.

"shortly after" ignition. First ignited

(test burn) @ 1235 hrs. Shortly after

ignition two spot fires occurred. 1st

spot was contained. 2nd spot grew to

2 acres then 4 acres getting into steep

terrain and not safe for ground forces.

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Yr

Agency

Unit

State

Complexity

Rating

Veg/Fuel Complex

22-Jun

Grass, oak brush &

riparian veg.

Forested outside

2-Jul

<3 hrs. Test fire @ 1050 hrs. Multiple

spots at different locations. Declared

@ 1330 hrs.

Juniper

18-Aug

NR < 1 day. No chronology included

NR

CA

100

2,000 including pvt

Low

+ 23 homes

ID

NR

NR

1998 BLM

UT

Lowden Ranch

1999 BLM

Redding Field

Office

Wilson Gulch

(missing append)

1999 BLM

Burley Field

Office

NR

NR

2

Length of time from Test Fire or Ig

to being declared an Escape

< 1day no chronology included. Spot

fires or slopovers that were more than

holding forces could handle was one of

noted factors.

Blacklining

Pahcoon

278

Season of Ig

(mo/day)

29-Apr

Cheat grass with

heavy "above

normal" loading

Cedar City

District, Dixie

Resource Area

OR

FBO Fuel

Model &

Modeling

5 hrs. Firing began in NW corner ~

1130 after briefing. 1230 began having

problems w/ spotting. 1300 stopped

firing and took holding actions in NW

corner. More spots along N-side line

@ 1430. 1530 one acre outside unit

on pvt ground. 1630 declared an

escape.

NR

Klamath Falls

Resource Area

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

Escape Size and

Consequences

10 acres inside unit

plus 29 acres on

NR

Pvt - timber lands

1998 BLM

Fox Lake

Planned Acres

Appendix A

NR

NR

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Cerro Grande

EB-3

Mt. Como

Yr

Agency

Unit

2000 NPS

Bandelier NM

2000 BLM

Arizona Strip

Field Office

2000 BLM

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

Carson City

Field Office

State

Planned Acres

Escape Size and

Consequences

Complexity

Rating

Appendix A

Veg/Fuel Complex

NM

Three phase

48,000 plus pvt w/

project. 1st of 3. 280+ home/

Moderate - hand Multiple

Approx. 900

structures

AZ

3 acres "test"

subunit

NV

197 acres

Damaged pvt

property

Multi-unit project.

1st burn in 1997. NR

EA done 1996

NR - a burn plan

was not

NR

prepared for this

"test" unit

NR - Elements

rated as "high" Pinyon with litter/duff

missing rationale & brush that provided

and mitigations. ladder fuel

Hand ignition

3

FBO Fuel

Model &

Modeling

NR

Season of Ig

(mo/day)

Length of time from Test Fire or Ig

to being declared an Escape

4-May

1 day

Ignited

3/31/2004.

Declared

4/13/04

13 days.

2 days Had 11 people & 2 engines to

hand ignite area, but no direct access

to unit for engines. Ignition went well,

Oct 18

but fire burned into the evening &

Started Ig 1325

actively backed down hill all night.

Done by 1700

Next day no new ignition & tried to

Oct 20 Declared

contain area already lit. A forecasted

1645

wind event kick up fire & spotted

outside of unit from unburned island

inside unit.

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Yr

Agency

Unit

State

Planned Acres

Escape Size and

Consequences

Alkali Rim

(Near Miss)

2001 BLM

Worland Field

Office

WY

1,200 to 1,500

N/A.

This review was

about the need to

use escape routes

during burn ops.

Cordgrass (escape

named Pin Oak)

2001 FWS

Marais Des

Cygnes NWR

KS

80 acres

13.6 acres w/ 4

acres on pvt

Navajo Ridge

North Shore Kenai

Lake (Draft)

2001 FS-R4

2001 FS-R10

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

Dixie NF

Chugach NF

UT

AK

Complexity

Rating

Appendix A

Veg/Fuel Complex

Season of Ig

(mo/day)

Length of time from Test Fire or Ig

to being declared an Escape

Low, but did not

follow agency

Juniper with

policy. Should sagebrush/ grass

have been

intermixed

Moderate

N/A

20-Sep

N/A

Low

FM 3 inside

FM 3 & 9

outside

28-Oct

11 days

28-Jun

4.5 hrs. Test burn conducted @ 1300

hrs w/ no holding problems. Ignition on

unit occurred from 1400-1500 hrs. Ig

stopped due to spotting, holding crews

contained and Ig resumed @ 1700 hrs.

At 1730 hrs, more spotting occurred

and several slash piles were ignited.

Declared at 1736 hrs. Contained 2000

hrs.

5-Jun

10 days. Area was monitored &

patrolled according to the plan.

Evening of 6/25 spotfires outside of

unit discovered. Increasing winds

caused spotfires to spread beyond the

capability of local resources.

cordgrass

Project 199, mult.

units. 26 ac w/ 2 8.2 including pvt

units previously lit

NR

1,000

Reported

"complex" no

Bug-killed spruce

doc. of analysis aerial ignition

NR

FBO Fuel

Model &

Modeling

Lopped slash w/

subalpine fir and

aspen outside units

4

Not Reported

(NR)

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Pot Creek (DRAFT)

Rock

Wilson

Anderson/ Danskin

(this review covers

2 separate burn

project areas)

Yr

Agency

2001 BLM

2001 FS-R5

2001 FS-R1

2002 FS-R4

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

Unit

Craig Field

Office

Tahoe NF

Lolo NF

Boise NF

State

CO

CA

MT

ID

Planned Acres

Black lining with

261 ac area

200

706

3,500

Escape Size and

Consequences

250 - 300 acres.

Suppression cost

$50.0 ths.

201

Complexity

Rating

NR

NR

none outside

High - aerial

planned boundary ignition.

405

High - aerial

Appendix A

Veg/Fuel Complex

FBO Fuel

Model &

Modeling

Season of Ig

(mo/day)

~3 hours. Test fire completed by 1315

hrs. Ignition began around 1330 hrs.

A "significant wind event" occurred

1525 hrs. w/ winds out of the west at

30-40 mph driving the fire across the

east line. Winds reported to begin

dying down around 2300 hrs.

Sagebrush

NR

Long needle

pine/white fir

5 hrs. (2nd day of Ig) Test fire @

0715 hrs. Ignition started @ 0800 hrs.

FM 9 in, FM 10

RH drop dramatically bwtn 0800-0900

May 9th part of

outside.

hrs, but still in prescription. 1030 hrs.

unit successfully

Continuous

RH drops to 19%. 1100 hrs RH 12%,

ig. May 10

frost-killed

winds increase to 5 mph. Contingency

proceeded to

brush @

forces called. 1130 numerous spots,

complete ig

escape

more resources ordered. 1222 hrs

more spots which grew, more

resources ordered. Declared 1230.

Dry timber types,

mostly northerly

aspects

FM 2/10/9. FM

selection not

issue.

Smoldering in

Lrg 1000 hr

fuels was

PP/DF intermixed w/

sagebrush/ grass

5

4-Sep

Length of time from Test Fire or Ig

to being declared an Escape

Four different

days for

ignitions. April

25-26, May 9

and May 11.

Declared an

escape May

24th.

29 days. Declared an escape due to

"logistical and financial" concerns. The

burn was NOT outside planned

boundaries.

15-May

4 days Two different landscape scale

burns ignited the same day. Both units

had previous ignitions weeks before.

Snow remained on northerly slopes

and checked surface spread of fire.

High winds (30-35 mph) from a passing

system caused both burns to escape

planned boundaries at the same time.

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Yr

Agency

Sanford (this review

covers 2 separate 2002 FS-R4

burn project areas)

Blanco

Cascade II

Cherry

2003 BLM

2003 FS-R4

2003 FS-R3

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

Unit

Dixie NF

Albuquerque

Field Office

Uinta NF

Prescott NF

State

UT

NM

Planned Acres

3,500 total in 2

separate RxB

NR

Escape Size and

Consequences

78,000

NR

Complexity

Rating

Appendix A

Veg/Fuel Complex

FBO Fuel

Model &

Modeling

Season of Ig

(mo/day)

Two separate

days of Ig on

two different

burns 11 miles

apart. April 22,

May 13

NR

Low

UT

1,000 (in BP)

Ignited 400 not in 7,828

BP

High

AZ

Project 8,141 2nd 150 ac slopover +

of 3

992 ?

NR - hand &

aerial

6

Ponderosa Pine but

w/ significant P-J

Heavy, mature oak

brush intermixed with

aspen

Chaparral

Incorrect FM

selection - used

FM 8. Review

recommended 4-Jun

using a

combination of

FM 4 & 6

Length of time from Test Fire or Ig

to being declared an Escape

30+ days

3 hrs. Test fire 1200 hrs - 2-4' FL with

occasional torching. Ig stopped 1245.

1300 hrs spot fire reported on top.

1345 hrs burn personnel unable to

contain. Declared 1500 hrs. ~16001700 hrs more resources ordered

(engines, tanker, T-1 crew).

23-Sep

5 hrs. Test burn @ 1230 hrs. Second

ignition in different location 1320 hrs.

Spots occurring in 3 different locations

@ 1430 hrs, 1515 hrs & 1630 hrs.

Declared 1700 hrs. 1720 hrs holding

forces retreat to designated safety

zones.

16-Jun

1 day. Ignited 6/16. "Unpredicted wind

event" shifted wind direction. 150 ac

spot occurred and contained. 6/17 no

new ig., mopping spot. New spot 6/17

@ 1300 hrs.

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Yr

Agency

Petty Mountain Near

2003 FS-R4

Miss

Puma

Sink's Canyon

2003 FS-R2

2003 BLM

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

Unit

Ashley NF

Black Hills NF

Lander Field

Office

State

UT

SD

WY

Planned Acres

1,000

Escape Size and

Consequences

Veg/Fuel Complex

FBO Fuel

Model &

Modeling

Fuel Model 8

covered 80Primarily Sagebrush 90% of area

w/ aspen

with isolated

pockets of FM

10.

Not declared (Total

NR

ac burned 2,593)

Project 800 w/ 11

units. Completed

231 acres on 2

NR

units prior to

lighting another 2

units that escape.

NR

Complexity

Rating

Appendix A

Low - hand BB.

Reviewers

questioned

whether RxB3

Ponderosa pine

was correct

"management

oversight"

Rated Moderate WUI. According Majority NR,

12.76 acres outside

to BLM 9214 all decadent bitterbrush

MMA on PVT

WUI should be & P-J

rated High

7

Season of Ig

(mo/day)

24-Sep

Length of time from Test Fire or Ig

to being declared an Escape

Was not declared an escape.

1+ days? Had been "blacklining" on

one of units during two previous times

in March. March 31st continued

Blackline Unit 3

blacklining on one and started on

March 14 & 25,

another unit. During interviews, burn

Ig on Unit 3 & 5

personnel mentioned holding/spotting

March 31. April

problems. No holding or monitoring

1 Ig & declared

overnight. Declared April 1st after fire

behavior increased & made significant

runs inside and out of target units.

Majority FM 2,

FM 6 not used

in BP to

10-Apr

account for

brush inclusion.

5 hrs. Test ig @ 1130. 1200 hrs

blacklining started. 1400 hrs ig of

interior. 1640 hrs winds switch, RH

drop & spots across line. Not declared,

but later determined outside of MAA.

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Impassable Bay

(Compartments 16

& 117)

Island Lake

Long Jim III

Yr

Agency

2004 FS-R8

2004 FWS

2004 NPS

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

Unit

Osceola RD,

NF's of Florida

Imperial NWR

Grand Canyon

NP

State

FL

AZ

AZ

Planned Acres

Escape Size and

Consequences

Complexity

Rating

Appendix A

Veg/Fuel Complex

Individual burns

rated low, but

burned together

(adding

helicopter &

other mixed

1,500 in two units

resources)

32,000 + including

Long-leaf pine &

16 = 1,000 117 =

indicated should

state & pvt lands

"swamp"

500

have been

Moderate to

High. No

documentation

on "final"

complexity

rating.

630 acres

Project 5,050.

1st of 3 for 1,618

Estimated 200

acres

Moderate

NR - one

element of

analysis was

raised as an

issue

8

FBO Fuel

Model &

Modeling

Season of Ig

(mo/day)

Length of time from Test Fire or Ig

to being declared an Escape

FM 7 (southern

Rough) and FM 2-Mar

4 (dry swamp)

5 days before "officially" declaring an

escape, but approx. 3 hours after

ignition the burn was out of prescription

& should have been declared. A test

burn was conducted, but not

documented. Estimated from report to

have been around 1100 hrs. At 1400

hrs obs flame lengths of 20',

(prescription called for 4-6') which

exceed prescription.

Fuel model 3.

Cattails (8-10 ft),

Appropriate

phragmites (common model selected

reed, 8-10 ft) also

but under 4-Feb

intermixed with salt estimated

cedar

potential fire

behavior

< 2 hours. Test fire @ 0945 hrs. Fire

behavior and smoke Rx met. Ig begins

@ 1000hrs. At 1030 hrs. east flank

widen w/ aerial ig. At 1040 hrs

remaining unit lit in 2 passes. 1050 ig

halted. 1105 hrs possible spot across

river. Confirmed 1110 hrs. Declared

1115.

Ponderosa pine w/ PJ FRCC 3

Ig time NR, but aerial ignition

completed 1100 hrs. Spotting reported

@1143 hrs. Declared @ 1517 est. 6+

hrs. Ignition was to be completed by

0900 hrs due to observed burning

conditions during blacklining ops a

week before and during test ignition

that day.

5-May

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Meadow

Mitchell & Hot Air

(this review covers

2 separate burn

project areas)

Yr

Agency

2004 BLM

2004 FS-R3

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

Unit

Fillmore FO/

Fishlake NF

Clifton RD,

ApacheStigreaves

State

UT

AZ

Planned Acres

200 acres. Prior

burning in spring

on same project.

500 ac in project.

Escape Size and

Consequences

Complexity

Rating

524 acres. Only 2

inside unit.

Included PVT &

state land. Closed NR - RxB2 with

hwy due to smoke. hand ignition.

Burned power

poles, cut power to

town.

Planned 5,000 to

1,537

7,000 acres

Appendix A

Veg/Fuel Complex

Sagebrush with

cheatgrass & thinned

P-J. Increase fuel

loading of cheatgrass

at time of burn.

Individual burns

Low - Mod. Ig

together should

Multiple types

have raised

including ponderosa

complexity.

pine. Others not

Also, content of

mentioned.

complexity

analysis found to

be lacking.

9

FBO Fuel

Model &

Modeling

Season of Ig

(mo/day)

9-Sep

Fuel model 8

was used for

complexity, but

prescription

parameters

used more

12-May

volatile fuel

models 4 & 9.

Spotting

distances were

not calculated.

Length of time from Test Fire or Ig

to being declared an Escape

< 1 hour. Test fire Ig 1545 hrs. Two

engines released to respond to wildfire

1550 hrs. Decision to "shutdown" and

suppress test fire. Spot fire noticed @

1602, within ~8 minutes spot grows to

30 acres. Declared @ 1625 hrs.

Winds increased & shifted with T-storm

activity. Spotting

6 days Concurrent ignition on two

separate projects. First planned

ignition delayed due to high wind

assoc. with weather front passing.

Begin ground ignition next day.

Following day proceeded with ignition

by hand & aerial.

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Appendix B

Project Name

Anatomy of the Escape - What were the "weak signals"

Key Lessons Learned / Emerging Best Practices / Knowledge Gaps

Lizzie Springs

Appeared to review team to be "well planned and properly executed, but inadequately

documented." Knew the head of Lizzie was problem area - fuels and no natural barrier. Two

other burns "successfully completed" after this burn, but several days after this burn was

ignited two other burns in the state escaped and local personnel knew of these escapes.

During 1996 "drought" conditions existed affected heavier fuels more than normal, area was

known to have heavier fuels. On the 8th day, the fire escaped "due to high wind event", but

it seems that many signals were potentially missed.

Burn Plan based on "normal conditions" yet burn personnel proceeded with plan and did not

make "adjustments" to burn plan or operational procedures even knowing that there was

"heavier than normal" fine fuels and with drought conditions that the heavier fuels could be

effected even though they knew the area had heavier fuels. They knew the Wx was

"unusually, warm and windy". Patrolled for 5 days and even with smokes still in unit assigned

resources to other burn projects. There was a shortage of "qualified" personnel and this

contributed to inadequate mopup & patrol. The key people involved were "fully trained &

experienced", but their numbers were barely adequate to execute a single burn let alone

multiple projects.

Pinatosa

Shades of Cerro Grande - Snow delayed initial ignition. Spring time with public "knowing"

about strong, erratic winds. In this case, technically lit outside of prescription elements

and/or shortly after ignition the Wx conditions exceeded prescription. The report mentions

that the test fire location used during hand ignition was not representative of fuels or

environmental conditions (more shaded and sheltered than unit). Many problems with burn

plan and prescription development. Burn plan preparer not qualified nor very experienced.

RxB not experienced with burning in these fuel types. Trust with Wx Service was low

because of earlier "blown" forecast that did not predict snow storm which caused a delay.

In this state (NM), there may be a need to better understand seasonal patterns of winds or

wind events during transitional seasons. Wind and Wx patterns in general need to be

understood locally, seasonally and what effects larger Wx influences can have on a burn.

This burn is approx. 80 air miles from Cerro Grande. The review noted that the burn boss

(although qualified) did not have experience of the with fuels types & may have contributed to

practices leading to the escape.

Banner Queen

One of two burns involving use of a contractor - other burn was Fox Lake. The review noted

that the burn plan was well developed and prepared. The execution of the burn was done

well and going well. Two things directly linked to escape although was not giving enough

consideration to fire effects of the grass component in the predominate brush models used

(with high live to dead ratio). The grass component repeatedly came up in interview (a

surprise to burner?). Knew it could be a problem, but focus was on the brush not fully

appreciating what the added grass would do. Experiences with wildfire that year may have

misled personnel into believing spread would NOT be a problem. The burn plan did not

reflect changes in fuel structure so not planned for with the test fire. 2nd Helicopter

malfunction was also mentioned as a direct cause of escape because it was not able to help

ground crews suppress second spot when it got into steep ground.

One lesson learned raised here concerns mechanical failures. While redundancy in human

systems may not work well, redundancy for mechanical devices does work. When

mechanical equipment is key to burn operations and/or holding capacity it may an area to

consider and make sure your contingency plan covers this such as having another helicopter

with suppression capability on standby-by for quick response. The complexity of the

vegetation-fuel complex surprised burn personnel. Also, previous experience with wildfires

that year may have "signaled" to burners that this fuel combination was more "flammable"

than believed. Local manual direction DID NOT reflect current national direction.

Supplemental burn plan was NOT signed by agency administrator.

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

1

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Anatomy of the Escape - What were the "weak signals"

Appendix B

Key Lessons Learned / Emerging Best Practices / Knowledge Gaps

Fox Lake

The review noted that the contractor did not transition quickly enough from firing to holding.

Did not take on-site 10-hr dead fuel moisture samples nor requested a spot weather as

This is the only escape that involved using a contractor which prepared and conducted the required. Used only general zone forecast. Weather obs. from on-site indicated parameters

burn. The review determined the burn plan was adequate and all people including the

were near the drier end of the window when ignition was started & conditions seemed to be

contractor were qualified. However, contractor did not sample fuel moistures outside of unit out of prescription quickly. All ignition had been stopped and in holding mode when out of

on PVT where it was more open therefore drier. Lit on "drier" end of Rx. Lighting too much prescription parameters. The morning of the burn unit was selected over another because

too fast was noted as a contributing factor. Contractor also did not get spot Wx forecast as the other unit was "too wet" (unknown if this influenced burn boss assumption that is unit

required in burn plan. The review noted that since contractor is "paid by the acre" that this would not cause concerns with control, not raised as an issue in report). On-site weather

may have played a role in choices to proceed with ignition. There was "prolific" spotting

obs. were not taken in a representative area of conditions (winds taken in sheltered area,

which combined into 3 "major slopovers" outside unit all onto pvt ground.

area that was source of spotting was in near an exposed ridgeline). Also, recommended that

10-hr needed to be monitored at least a day prior to ignition and if conditions outside of unit

are different those areas should also be monitored.

Pahcoon

Review noted that all burn personnel were qualified for their position, but noted that

The review concluded that there was a "failure to adjust operational procedures" to reflect

experience in Rx fire and in this fuel type varied considerably. The lack of expereince in this

the additional on-site fuel loading and an attempt to black line on the "extreme upper end of fuel type of the burn boss was noted as a contributing factor. Burn plan was written for

the prescription". The plan was written for "normal" conditions, but that year there was

"normal" conditions, and noted it is up to burn personnel to adjust when conditions are

"above normal" ppt so "heavy" loading from cheat grass was created. RxB did note the extra different than planned. Recommended that for burns with considerable "blacklining"

grass and added engine and "pumpkin" to compensate. RxB had little experience in this

operations to write seperate prescriptions parameters (Note: this is currently in BLM policy

type. Brush component was above "optimum" (i.e. wet or high live fuel moisture), but grass and burn plan templates). Inter-office coordination also needed to improve as well as

fully cured.

communication & cooperation with other agencies. Burn was adjacent to an Indian

reservation, but when escape occurred they were not notified of escape.

Lowden Ranch

Two firing crews. 1115 RxB concerned abut fire getting into trees, but holding actions

mitigated concern. 1145 RxB (T) reported "good progress" and asked if should continue.

Given Ok from RxB. 1200 hrs RxB(T) noticed spots. Ig stopped, holding action contained

There is extensive documentation on this escape so it was not summarized here at this time.

and 100% mopup was proceeding. Ig resumed @ 1220. At 1300 hrs spot reported in area

of initial concern and it was also contained. 1320 hrs 3rd spot spread quickly and exceeded

holding capability.

Wilson Gulch

(missing append)

Burning in juniper necessitate wide parameters (RH, temperature, live fuel moisture, and

wind speed/direction) that would be considered "high". Based on some of the

recommendations it appears this burn used a combination of blacklining and "nighttime"

recovery for containment lines. The review only mentioned that one night did not get

expected recovery. Also, based on review team recommendations it seems that burn

personnel were not involved in the upfront (during NEPA) planning and selection of the area

to be burned. Also, the NEPA document and analysis did not allow for use of dozers which

limited options for the burn personnel to implement.

Prepared by D.Dether

Forest Fuels Planner, Boise NF

2

Missing documentation may have had additional information mentioned in report. Need to

have all pertinent information in reviews (this review talked more about what the review team

talked about than providing the content and context of their discussions). The review

seemed to indicate testing a newer approach to burning that would have benefited others to

have more information and share results with other burn personnel. Importance of having

prescribed fire experience at the planning table to help with project design, allowable burn

areas and to ensure activities or practices that will likely be employed during burn operations

(e.g. use of dozers) are appropriately analyzed and disclosed in the NEPA document.

6/29/2005

Prescribed Fire Escape Reviews

Project Name

Cerro Grande

EB-3

Mt. Como

Anatomy of the Escape - What were the "weak signals"

Appendix B

Key Lessons Learned / Emerging Best Practices / Knowledge Gaps

There is extensive documentation on this escape so it was not summarized here at this time. There is extensive documentation on this escape so it was not summarized here at this time.

The review attributed the escape to "failure to adjust operational procedures (holding and

mopup) to reflect the changing weather conditions. Available fuels during ignition included

only the upper needle cast which was dry & consumed. Duff layer was wet and not

consumed. Large fuels (logs) were not consumed. Fine fuels (<3") were reduced by 6070%. 1st and 2nd weeks after ig, units each checked each day. Smokes were obs, but

minimal mopup occurred due to " test" nature of the burn. Into 1st week after ignition,

agency's unit suspends any new ignitions because weather conditions "became too dry".

The day prior to the escape, patrol notes smokes and open flame in unit, but did not think

there was a risk of escape. The day of escape patrol noted smokes in unit and also did not

think it posed a significant risk of escape. Seven hours later "significant smoke" was

reported in the area. Leadership (Officer manager, FMO, FCO out of town), the RxB in

office, but doing other work. General weather forecast for that day call for temps in mid-70's,

RH's in teens and SW winds 20-30 w/ gust to 40 mph.

Small burn, testing a "technique" for larger application. Did not constantly staff burn nor had

an individual directly responsible for burn until declared out. Were personnel lulled into

complacency since it was a small (3 acres) test unit? Trust (lack of confidence) in weather

forecasts was mentioned in report, but not cited as a reason contributing to the escape. The

"burn plan" used (the test unit was not included in it) did not have "triggers" identified for

mopup or contingency actions. Technically, there was no burn plan for this test burn.

There were no natural barriers or line constructed in places to contain burn area. Potential

fire behavior was noted in the complexity analysis as a significant issue, but no specific